The timing of the announcement that Voyager 1 has, for some time now, been an interstellar spacecraft came just before the 100 Year Starship Symposium and was certainly in everyone’s thoughts during the event. Jeffrey Nosanov (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) reminded a Saturday morning session led by Jill Tarter that when the Voyager program was conceived, the notion of going interstellar was the furthest thing from the planners’ minds. Voyager’s adventures beyond the heliopause are what Nosanov now calls ‘almost a completely accidental mission.’

How to follow up the Voyager success? For one thing, we already have New Horizons on its way to Pluto/Charon, with flyby in 2015, and I’ve already discussed the New Horizons Message Initiative, which would upload the sights and perhaps sounds of Earth to a small portion of the spacecraft’s memory after its encounters are done (see New Horizons: Surprise in Houston for more). But Nosanov asked Voyager project scientist Ed Stone, himself all but legendary in his association with the spacecraft, what he would like to see happen next. Stone said he’d like to see ten or a dozen spacecraft sent out in different directions to the same distance.

Image: JPL’s Jeffrey Nosanov, whose work now includes a study of next-step missions beyond Voyager.

Nosanov’s recently accepted proposal to NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) Program will examine just that scenario. What he plans to do is to design a spacecraft architecture that will probe what the project description calls ‘ the unique regions of the Heliopause, known as the nose, sides, tail, north and south.’ Flybys of the outer planets and Kuiper Belt objects as well as studies of the heliopause itself are what Nosanov has in mind, but he goes still further, looking toward reaching the Sun’s gravitational lens at 550 AU and beyond to study imaging of the center of the galaxy and other targets at various wavelengths.

State of the Universe

Speaking of working at various wavelengths, the morning “State of the Universe” session began with project scientist Adrian Tiplady discussing South Africa’s role in the Square Kilometer Array, itself a multi-national collaborative project whose 3000 small dishes will carry ten to one hundred times the traffic of the global Internet at any one time. The MeerKAT installation is a precursor for the full array, one whose 64 dishes will make it the largest radio telescope in the southern hemisphere until the Square Kilometer Array is completed some time in 2024. Extending across a number of African nations and into Australia, SKA will be fifty times more sensitive than any other radio instrument, a huge challenge in engineering as well as collaboration.

The State of the Universe panel was a lively session, held in the Hyatt’s ballroom and sparked by an enthusiastic Hakeem Oluseyi (Florida Institute of Technology), who offered an overview on our attempt to find dark matter and a whirlwind tour of the early universe following the Big Bang. Oluseyi sees the universe as a place that selects for life-forms that populate the cosmos because planetary existence is sharply limited by extinction events and resource depletion. “Intelligence is needed to move into space,” he added, “but the window of opportunity is finite. Single cell life-forms survive out of robustness, but complex beings need to exploit resources to move into space. Every life form on every planet is in a space race.”

Image: Florida Institute of Technology’s Hakeem Oluseyi, whose rapid-fire tour of the early universe challenged the skills of even this very fast typist attempting to take notes.

I’m skipping a lot of good material to compress this, but I do want to mention that the discussion of exoplanets by David Black (Lunar and Planetary Institute) and Ariel Anbar (Arizona State) brought the crowd up to speed on Kepler — now without fully functioning gyros but sporting a huge list of exoplanet candidates — and methods for studying biosignatures in the atmospheres of distant worlds. Jeff Kuhn’s discussion of the Colossus telescope was a fitting cap to the panel. Kuhn (Institute for Astronomy Maui) described an Earth-based instrument that could perform a census of nearby planets looking for unusual thermodynamic signals. Explaining earlier searches for Dyson spheres, Kuhn went on to discuss how civilizations use power, noting that we use half of one-tenth of one percent of the total energy our planet absorbs from the Sun. Power consumption increases, of course, as civilizations become more advanced.

The inevitable result: The thermal signals Colossus is being designed to look for. The Colossus Consortium, a private organization funded by a wealthy individual, is looking for warm exoplanets that display the heat signature of a functioning civilization. Kuhn’s slide showing Paris in the infrared, a nighttime shot taken by a satellite, drove home the point that the thermal signal we produce is significant, measurable and much larger than what we produce in light. The intention of the Colossus builders is to examine stars within 60 light years for such markers, which would be usefully free of our sociological speculations about what such a civilization might do.

Breakthrough Telescope Technologies

It’s a fascinating concept, and to see more about it, read SETI’s Colossus in these pages, or visit the Colossus site. What I like about it is that it makes no assumptions about why or how an extraterrestrial society might choose to communicate, but depends solely upon its activities on its own world. Joe Ritter, a colleague of Kuhn on Maui, went on to lead a track called “Destinations: Hidden Objects” later that day that delved into the difficulties in exoplanet detection and viewing. Ritter ran through Kepler’s woes and discussed Hubble, the James Webb Space Telescope, and the lamented Space Interferometry Mission that may live on in missions like Darwin.

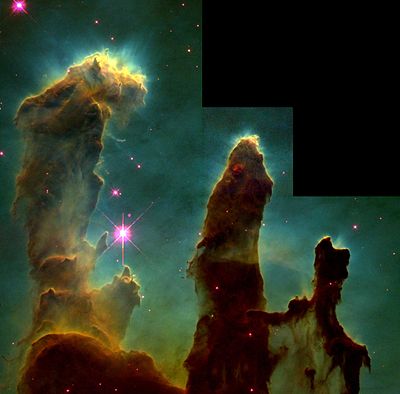

And with a gorgeous slide of the famous “Pillars of Creation” region in the Eagle Nebula, he also made the point that instrument effects limit our ability to see. Check the image below to confirm Ritter’s point: The bright star at center left does not actually have a cross-like shape, reminding us that diffraction spikes can swamp signals of faint objects in even the best of telescopes. Off-axis telescope designs, which he illustrated, can help in reducing diffraction — the Solar-C experimental coronagraphic telescope on Haleakala is an example of how this can be done.

Ritter went on to discuss the uses of polarization, describing forms of spectroscopy that can use polarization to scale away randomly polarized light and leave a more workable signal. With such methods we can hope to separate the light from an exoplanet from the light of its star. The PLANETS telescope (Polarized Light from Atmospheres of Nearby Extraterrestrial Systems) has as its goal to define the atmospheric composition of exoplanets. This one is a 2-meter off-axis telescope now under development at the Institute for Astronomy of the University of Hawaii.

Joe Ritter is a great conversationalist and we enjoyed kicking these and other ideas around after hours at the hotel bar. He’s fascinated with producing thinner apertures and how thin membranes as mirrors can be manipulated by tiny actuators to retain their shape. Polarized light at particular wavelengths can be used on the right materials to create adaptive optics in which the mirror doesn’t actually have to be touched to be re-shaped. Imagine a Hubble-sized mirror (2.4 meters) weighing in at no more than one pound, or a JWST aperture weighing twelve pounds. If we can make such giant apertures, we can use them not only for telescopes but for communications or, dare I say it, as solar sails. This work is so revolutionary in its potential that I’ve asked Joe to write an article about it for Centauri Dreams to explain it in more detail. “Brute force isn’t an elegant way to produce the mirrors we need,” Joe told me. And from what I can see, the work in his lab is both elegant and paradigm-shifting.

Image: Joe Ritter, a name you’ll be seeing much more of on Centauri Dreams in relation to his work on extremely light and thin telescope apertures.

Uses of Science Fiction

Saturday was the symposium’s last full day, so it was perhaps understandable that sessions ran over in the attempt to cram everything in. All of this led to one of the most entertaining episodes of the event, Marc Millis’ talk “From Sci-Fi to Scientific Method: A Case Study with Space Drives.” Marc frequently draws on his work as head of NASA’s Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Project, but this talk is light on equations and long on imagery from science fiction films and how scenarios from such films can inspire creative thought.

An example: We constantly see spaceships in movies where the crew is walking around under what seems to be normal Earth gravity, and as far as we can tell, there is no problem with inertia even when the craft suddenly accelerates. Now if you could actually do that, Millis asks, why wouldn’t your plots take advantage of the fact? An intruder on board wouldn’t need to be handled by security forces. Instead, why not just manipulate the gravity in his location to bounce him off the walls, rendering him unconscious? And drawing on films ranging across the gamut of recent science fiction, Millis extracted scenarios and the questions they raised.

The more serious point is that even a bad science fiction movie can become a spur for thought that encourages new angles into old problems. The key is to promote creativity. Marc had to be amazingly creative himself during his presentation. When I arrived, the late-running panels in the ballroom meant that most people were still there. When Marc was almost at the end of his talk, the room suddenly filled with people, taking up the chairs and sitting on the floor. Without losing a beat, Millis simply went back to the beginning and presented the entire talk a second time. I do a lot of public speaking but I have to say this was something of a tour de force.

Image: Marc Millis amidst an impromptu reprise of his talk.

I wish I had been able to report on all the talks I attended in these pages but I didn’t have time to run through each. What a year this has been in terms of interstellar conferences. And we still have one to go, a Starship Century event to be held Monday October 21 at the Royal Astronomical Society on Piccadilly in London, with Royal Astronomer Martin Rees as a featured speaker. As I get more information about speakers at this one, I’ll pass it along, and will plan on covering the sessions via live streaming as my travel budget won’t sustain another conference this year.

It used to be that people interested in interstellar flight met in off-schedule gatherings at meetings on other subjects. The explosion of conferences this year is probably unsustainable, but it will be interesting to see what kind of schedule eventually emerges. In any case, it has been a year to remember, one that has put an exclamation point on deep space dreams capped by Voyager, our first interstellar traveler.

“Stone said he’d like to see ten or a dozen spacecraft sent out in different directions to the same distance.”

That would be fantastic. A whole fleet if interstellar vehicles.

I take it that Ed Stone’s plan confirms what I understand to be the case, but which nobody seems to want to say explicitly: that the distance to the heliopause is different in different directions and at different times in the solar cycle.

Stephen

Ten or a dozen spacecraft sent out in different directions to the same distance- that would be fantastic, a fleet of interstellar precursor probes!!

Joe Ritter’s work sounds very interesting… I’ve been fascinated by advanced telescope designs for some time, after I read the answer to the question “What is our ultimate limit to seeing things clearly?” in Sten Odenwald’s Back to the Astronomy Café. The staggering potentialities of one-micro-arcsecond imaging technology- seeing a planet orbiting Alpha C as clearly as a six-inch telescope shows Jupiter!!!- really captured my imagination. From then on I have dreamed of huge deep-space telescopes able to capture images of other Earths.

Amateur telescope makers (ATMers) are already familiar with the effects of diffraction and have even designed and built various off-axis telescope designs. Instruments like the Schiefspiegler and Yolo to get the clarity of an unobstructed aperture combined with the perfect color correction of a reflector telescope. They end up looking pretty strange… you can see some of these telescopes at Dave Stevick’s Weird Telescopes page.

A quick web search for off-axis or unobstructed reflectors coupled with ATM turns up some pretty involved discussions!!

I wonder if any amateur-designed off-axis telescope designs would be applicable to a scientific instrument? Many innovations in telescope design that later became widely used have been the work of skilled amateurs.

Thinner apertures are another fascination of the ATM community, when they get into sizes greater than 12 in. standard thickness blanks (those at a 6/1 thickness ratio) are impractically thick and heavy, so a lot of work as gone into thinner, lighter mirrors… with the danger that too thin a mirror can warp during grinding, causing astigmatism.

Guess the needs of the amateurs aren’t so far from the needs of advanced scientific instruments… who knows what we may find with the ability to build such light, thin telescope mirrors as Joe Ritter describes!! Not to mention the applicability for communications. Looking forward to hearing more about this very exciting work, for sure.

I don’t know of anybody dealing with one problem with FTL drives, navigating your way and making sure you stop where you want to. How do you see where you’re going if you’re going faster than light? And slower than light, how do you see upcoming obstructions?

On another topic, I wonder how much of a different view you’d get of various distant nebulae, at hundreds of AU from the sun?

stephen says: “I don’t know of anybody dealing with one problem with FTL drives, navigating your way and making sure you stop where you want to.”

That would be because FTL travel is impossible according to our current understanding of the way the universe works. Special Relativity pretty much tells us that no matter how long we accelerate a spaceship, the subsequent accelerations will get smaller and smaller the closer we approach the speed of light (C)… more and more energy goes into increasing the ship’s mass rather than its speed the nearer it gets to C. An object with rest mass would need infinite energy to accelerate to the speed of light.

Wormholes and warp drives are entirely hypothetical at this point, and may not be possible in the real world at all. Most physicists aren’t going to bother with navigating warp speed starships when it seems likely that we will never travel at warp speed.

That said, I recall that one of the problems with the Alcubierre metric is that a spaceship inside the warp could not see where it was going, or navigate the bubble… in fact, some versions would be created by a fixed, consumable trail of devices along the path of the ship ’cause the ship couldn’t create or turn off the warp from inside the bubble. No navigating.

With wormholes, some versions would require you to drag one end of the wormhole to your destination. I recall a physicist talking about an idea of capturing and inflating microscopic wormholes, but we wouldn’t be able to find out where they lead too until we went through it, kind of worrisome!!

All this is hypothetical, as I said. Hopefully if we ever do find out ways to create warp drives or wormholes, we won’t be limited to methods of travel that require us to already be at our destination before we can use it!!

“Power consumption increases, of course, as civilizations become more advanced.”

Is that necessarily so? I already see a shift in our own culture toward increasing the value of energy efficiency. It seems likely that other technological ETIs will encounter similar problems as us with regard to environmental damage of their home planet, and will thus be motivated as we are to lower their power consumption, not increase it.

Perhaps the ability to accomplish great things with very low environmental impact is the measure of a truly advanced society. If so, we may have great difficulty detecting them from here.

I think a major factor in the increase of interest for interstellar travel concepts are the exoplanet discoveries.

If this continues, and we do discover a Earth-like planet, I am certain this would give a moderate boost to space exploration efforts.

Very intriguing telescope concepts-I am looking forward to learning more about them.

With so many proposals for telescopes able to detect life, civilization and planets we might be coming to a “telescope century” ;)

Also I would be eager for more information about the conference in London.

@Peter Chapin In regards to increasing power consumption amongst advanced civilization, you ask, “Is that necessarily so? I already see a shift in our own culture toward increasing the value of energy efficiency.”

Generally, yes… increasing efficiency is a desirable goal, of coarse, and if a civilizations need for useful work remained the same while energy conversion efficiency increased, we would expect an advanced civilization to use less. But this is not the case.

As a civilization’s technology improves, it sets itself ever more ambitious goals that require more energy to achieve than the civilization produced before. This is simply because the amount of work– by this I mean the thermodynamic definition of work, force applied over a distance- required to achieve the sort of physical activity the civilization wishes to carry out increases. No matter the efficiency with which you use energy, a certain minimum quantity of energy will be required to achieve a physical task.

Inefficient energy-conversion tech requires still more energy to overcome losses, but more efficient methods only bring your energy requirements closer to the theoretical minimum required to carry out the necessary work.

As an example, if you were to use a pulley to lift a 10 kilogram weight five meters off the ground. The potential energy of the weight at the top of this height is PE=10kg*9.8ms^2*5m=490 joules, so the minimum amount of energy you must exert lifting this object is 490 joules. This is the absolute minimum of energy you must use to lift the weight. In practice some energy is lost in the friction of the pulley system and so on, but even if we replaced pulley with one with less friction, we would only lower the losses. At the end of the day you must cough up 490 joules to lift that weight plus any losses.

Sounds simple, but thus it is with even the most advanced civilization’s activities. Whether you want to light up a city, drive an automobile, or put a satellite into orbit, you must produce the required amounts of energy. Big feats like lofting a space station into orbit or lighting up Los Angeles require much, much more energy than squatting around a campfire roasting a wildebeest.* Progressively more ambitious efforts require handling progressively great amounts of energy.

Launching a human-carrying starship at, say, 10% C would require hundreds of times our current annual world energy production… a feat that sounds nearly impossible, until you consider that our entire annual energy production is only about one tenth of one percent of the amount of energy from sunlight that strikes the Earth’s surface every year.

That is not very much, cosmically speaking. With vast arrays of solar panels in close solar orbit, or fusion reactors running on fuel mined from comets and the gas giants a more advanced spacefaring civilization could supply these sort of energies to its rockets. This is what could enable star travel.

This also explains the average starflight enthusiast’s definition of an “advanced” civilization as “one that consumes a mega- &%*load of power”!!

*I would note that roasting meat by means of a fire in open air is not particularly efficient, as much of the energy is lost into the surrounding air. A closed stove can cook the animal while consuming far less wood fuel. ;-)

To stephen, one BIG speculation about FTL navigation:

http://dune.wikia.com/wiki/Guild_Navigator

Christopher: “As a civilization’s technology improves, it sets itself ever more ambitious goals that require more energy to achieve than the civilization produced before.”

Maybe. Maybe not. It sounds that, like Astronist, you are what I believe he calls a “plateauist”: one who assumes that advanced civilizations know no more fundamental physics than we do now.

That’s a big assumption, and one that is unprovable. As much as I am often heard in this forum chastising others about fictional physics prognostications, this is more about what we can reasonably do or expect to do in the near future. These may not be hard limits, just the boundary of human knowledge at this point in history.

We also cannot assume that ET will build bigger and bigger. We just don’t know.

Be careful or you will become a captive of your unwarranted assumptions.

Ron S: “These may not be hard limits, just the boundary of human knowledge at this point in history. We also cannot assume that ET will build bigger and bigger. We just don’t know. Be careful or you will become a captive of your unwarranted assumptions.”

You are essentially arguing that we cannot use currently understood physical theories* to place constraints on far-future civilizations because they might have magic unicorns that will grant you three impossible wishes when you catch them. Speaking of unwarranted assumptions, you seem to be holding to the common misconception that later developments in science somehow “replace” or invalidate earlier models, thus aliens may have “replaced” all our science and transcended its limitations.

This is not helpful at all, nor does it comport with the history of science. At this point in history, we humans have achieved a fairly good approximation of how the universe works, from the largest galaxies down to the realm of the subatomic… and it works. Satellites orbit. Lasers lase. Power plants behave as thermodynamics predicts. Reactors split atoms. Semiconductors conduct-some of the time.

Ever heard of the Correspondence Principle? It says that newer theories must agree with older theories where the older theory is verified by experiment. Newton’s laws are not shown to be all “wrong” by Relativity, in fact Relativity reduces to Newton’s mechanics at slow speeds. Since it is the universe we are describing here, there ARE hard limits- the limits imposed by the rules of the universe, which we can only describe, to various degrees of completeness.

Later theories never prove earlier theories “wrong”, rather, they show it to be incomplete and subsume it into a more general description of the universe applying to more situations. For a good discussion of this, see “The Relativity of Wrong” by Isaac Asimov.

The point is, the laws of physics we understand today apply to aliens anywhere in this cosmos. Even if they have a more complete description of physics than we do, all the same laws of physics we already understand will apply to them in the situations where they are proven to apply. Quantum mechanics did not invalidate thermodynamics and allow us to build perpetual motion machines. Neither will a GUT theory formulated by the inhabitants of a planet 6000 light-years away. In other words, we are doing SOMETHING right, or our technological civilization wouldn’t even work.

There is absolutely NO reason to assume that a society several thousand years more advanced than us could escape the fact that all physical activity requires thermodynamic work, or the dictum that all useful energy eventually decays into waste heat, or any other consequence of currently understood physics… and this will place hard limits on even the most advanced of civilizations.

Could aliens have much more complete theories of physics? Yes!! In fact, I consider it quite likely. But that does NOT mean that they can conveniently ignore the dictums of classical mechanics and relativity whenever it doesn’t allow them to do what they want. The real advantage of science is that it constrains us to describe the universe as it is, not as we want it to be.

Perhaps “they” have made new technologies based on extreme situations that their more complete theories can describe… like the creation of wormholes for interstellar travel. But you can bet that alien starships won’t be able to ignore, say, the law of gravitational attraction, or accelerate without applying a force.

I don’t know about “plateauists”- I simply know that there is a way the universe works, and we have a fairly good description of some aspects of the way it works. Not a totally complete description, but one that works where we apply it. It will work that way for aliens as well, and this gives us a chance to find what limitations apply to them based on our currently understood physics.

*And no, it isn’t “just a theory”. In science, a theory is a generalized description of how nature works with the capability to make predictions that have been widely supported by observation and experiment… a hypothesis is an educated guess that has not yet been supported by observations.

Stephen, one way to see where you’re going is to look behind you to see whether the actual rear view matches the computer simulation, assuming you can look out the back. For instance, if the engines were arranged in a ring and your viewpoint was from out of the unobstructed centre.

Christopher: “You are essentially arguing that we cannot use currently understood physical theories* to place constraints on far-future civilizations because they might have magic unicorns that will grant you three impossible wishes when you catch them.”

To start with an insult does your argument no favors. The entirely condescending reply is out of order. I understand science quite well.

But back on topic.

Do you claim that that, for example, there can be no physical method to move an object from A to B except using current understanding of work required? Of course this may be a total fantasy. Yet perhaps there will one day be discovered a method of doing so based on physics not known to humans in 2013. This would not (and could not, as you say) contradict current physics.

That *you* would constrain ET to *our* state of science knowledge is, in my opinion, limiting your ability to understand how they might operate. Our state of knowledge *does* limit us, now. Generalizing that to a universal truth is unwise.

Christopher: “Sounds simple, but thus it is with even the most advanced civilization’s activities. Whether you want to light up a city, drive an automobile, or put a satellite into orbit, you must produce the required amounts of energy.”

I understand what you’re saying and you make a good point. I’m still not completely convinced, however. While it would require mega-energy (okay… more than mega!) to send a spacecraft full of humans to the stars, we don’t actually know how many ETIs are interested in doing something like that.

Sending a 1 kg CubeSat to the stars might be a lot more energy efficient and perhaps with some suitable advanced technology that we don’t currently posses it would even be possible. Of course that’s wild speculation. Still, I can envision that some (most? all?) advanced ETIs might be more interested in sticking close to home and using their technological prowess to do things like deflect wayward asteroids from hitting their home planet… something that could probably be done without building mega-structures or using super-scale energies.

@Ron S My attempt at an analogy came across badly, and I can see now that it really was condescending and I should have thought twice before hitting the “send” button. For this I apologize.

Stated better, my point is that all the laws of physics we know about now apply to all hypothetical alien civilizations since “our” physics is simply a description of how the universe behaves, and the universe behaves the same wherever we can see in the universe, and presumably the space civilization under discussion share the same universe with us!

As long as we are boosting ships to ever higher velocities through space, yes. The only “out” I can see for this would be a breakthrough that somehow allowed us to travel between two points without building up velocity in the direction of travel, such as teleportation or inertialess drive. Only if an unexpected breakthrough in physics occurred could I see anything like this happening.

It might. For instance, teleporting “up” a gravity field (like if I used one gate on the ground to reach one on Mt. Everest) would involve a gain in kinetic energy… where would that energy come from if this method doesn’t do work on me to transport me? Or, maybe the teleportation only works if you reappear at a point where you have the same gravitational potential energy!! That way a “perpetuam mobile” will not be possible and conservation laws satisfied.

The only inkling of instantaneous teleportation across interstellar distances I have ever come across is vacuum hole teleportation. The object teleported would only be able to reappear somewhere that satisfied conservation laws. :-)

The interesting thing is that to maintain a uniform and linear motion does not require any energy, even if you travel an enormous distance, so the energy expenditure for teleportation across any distance should always be zero if the craft reappears with its state of motion unchanged.

Gravitational fields, of course, complicate things. The energy required to reach another point with vacuum hole teleportation would only be that required to alter the fields of force at points 1 and 2, as teleportation will not be possible if the fields of force are different at two points… as in the case where you teleport up 100km in Earth’s gravity field.

So, maybe we are both right, in a sense. We cannot be sure that a more complete physics may not turn up methods of travel that circumvent the current restrictions physics places on space travel. Nor can we be certain that this will happen, after all the universe is not required to satisfy our desire for “ahead warp factor 5, Mr. Sulu” starflight. And, ultimately, such breakthroughs must mesh with currently understood physics like conservation of energy and momentum.

I’m not a plateuist, so much. I want to travel “out there”. From the perspective of my (admittedly limited) 21st century mind distance, time, energy, and the rocket equation are obvious limiting factors for starflight, so stuff like giant fusion rocket ships and vast solar arrays become the obvious possible solutions. If a breakthrough happens, perhaps all this will become obsolete thinking, who knows? But we can’t know if such a breakthrough will happen or when it will happen. It would happen tomorrow, or it may never happen.

@Peter Chapin You make some very good points- we just can’t know how ET civilizations might choose to expand their presence to the rest of the cosmos, or how they might. Or even if.

Heck, we don’t even know what it would take to send a spacecraft full of aliens to the stars. Maybe some of “them” only weigh a few pounds and can enter a crytobiotic state, so they just remain inactive during what would be a multigenerational trip for humans, and are quite happy with only a few square feet worth of space even when awake!!

Sending tiny microprobes and nanoprobes isn’t wild speculation- several researchers have suggested it before. With technological advances in microelectronics and nanotechnology, we may be able to miniaturize many elements of a probe down to tiny sizes. Truly tiny nanoprobes could be dispatched via mass driver, tiny photon sails, or other EM techniques. Some researchers have proposed probes the size of coke cans or smaller.

There are some obvious criticisms. One is that even if we can build, say, a camera that is only a few mms across, the size of the lens needed for a high-resolution image is set by the laws of optics, so there is still a minimum size of the light-gathering area- and any communications devices, as well. That doesn’t necessarily preclude light weight… the probe might have a large size and very low density to have large enough cameras and sensors, as Robert Forward describes in his program for star flight.

Another concern is that microprobes might be at greater risk from radiation damage and impacts with dust grains. Thick shells kind of ruin the purpose of a microprobes. Still, some microbes withstand large amounts of radiation, and who knows what self-repairing future tech might be able to do? Also, swarms of microprobes could be dispatched to the stars, so even if many do not make it, some will.

And, yeah, we can’t be certain that ET (or even us!!) will commit to starship programs on the scale we currently imagine. Hopefully we would at least send probes, then. Maybe alien governments (and ours) will agree that deflecting asteroids and utilizing some space resources make sense, but balk at building million-ton starships. But we just can’t know what aliens would want, or even future humans… as Robert Forward said, “There is nothing so big and crazy that not one in a million civilizations will not be driven to do it.”

At least, some of the inhabitants of Earth have shown interest in these types of programs.

Christopher, thank you for the follow up. I think you are correct in saying we are not really far apart in our views.

“As long as we are boosting ships to ever higher velocities through space, yes. The only “out” I can see for this would be a breakthrough that somehow allowed us to travel between two points without building up velocity in the direction of travel, such as teleportation or inertialess drive. Only if an unexpected breakthrough in physics occurred could I see anything like this happening.”

Agreed. But then that was the point I originally made. I don’t see any promising leads in this direction but, then, who knows.

“For instance, teleporting “up” a gravity field (like if I used one gate on the ground to reach one on Mt. Everest) would involve a gain in kinetic energy… where would that energy come from if this method doesn’t do work on me to transport me? Or, maybe the teleportation only works if you reappear at a point where you have the same gravitational potential energy!! That way a “perpetuam mobile” will not be possible and conservation laws satisfied.”

In general relativity, the conservation laws are local, not global. This requires some care in what we mean by ‘local’, though in most instances it can be ignored. In a cosmological context energy conservation is routinely violated (e.g. red shifted photons).

One of the arguments against wormholes being physical is that it is possible to not only set up a photon feedback between each end of the wormhole, you can go beyond break even (perpetuum mobile) to energy conservation. This is related to why it is expected that singularities, if they exist, must have an enclosing event horizon: the potential energy of an infalling particle is infinite.

However there is nothing in physics that prohibits the creation or destruction of energy. The emergence of our universe is one example! But how it is done and its consequences are not well understood.

“The only inkling of instantaneous teleportation across interstellar distances I have ever come across is vacuum hole teleportation. The object teleported would only be able to reappear somewhere that satisfied conservation laws. :-) ”

I only glanced at your reference. I think the general case of such so-called teleportation is that of a non-simply connected spacetime. Wormholes exploit the same feature. Assuming that our universe is indeed a Riemannian manifold this type of connection is required for taking a short cut. If we’re embedded in a higher-dimensional manifold then there is the intriguing possibility of travel via that additional dimension. But without knowing the characteristics of this speculative space we can do nothing.

“…such breakthroughs must mesh with currently understood physics like conservation of energy and momentum.”

Strongly agree.

“But we can’t know if such a breakthrough will happen or when it will happen. It would happen tomorrow, or it may never happen.”

Also agreed. I was only pointing out that a more advanced civilization may have made further progress, if such progress is possible. Some speculative thought *may* help us to find ET better than only exploiting what we know to be true.

Oops! I made an error. Where I said “…(perpetuum mobile) to energy conservation…” I meant “…(perpetuum mobile) to energy amplification…”.

I am with you on the part about setting ever more ambitious goals, but not necessarily on those goals requiring more and more energy. There are plenty of ambitious things you can do that do not require great amounts of energy. You could write the Great American Novel, for example, or cure cancer. Many think that humanity’s ambitions have tended increasingly, and will tend increasingly, to be unrelated to increased use of energy or materials. I am with them.

Interstellar travel is an obvious exception, but we don’t know how much of a role this will play in an advanced society. If, hypothetically, in a few hundred years we are all AI’s beaming ourselves around on leaser beams, we may aim for small and efficient more than large and powerful. We may leave the traveling to Voyager sized (or smaller) probes equipped with the nanotechnology needed to build new (energy-efficient) industrial infrastructure around other solar systems. Complete with lots of cozy CPUs to beam ourselves to when the time comes and we feel like it. Travel time: Zero. Photon time, that is.

@Ron S Ah, no problem. Thanks for your reply as well. :-)

I don’t see any particularly promising leads in the direction of teleportation or intertialess drive either- and often FTL solutions like wormholes seem to require astronomical amounts of energy in the creation of them, even if you could take a spacecraft as simple as a Mercury capsule through one.

I don’t have enough knowledge of General Relativity to comment on energy conservation in GR… I intend to learn more about GR once I have the mathematical tools to understand it.

Yes, I’ve heard that it looks very much like conservation of energy was violated during the Big Bang, but I don’t know if that will also allow for the oft-sought “overunity” device that

have been suppressed by big oil/aliens/the Illuminatinever ever worked no matter how many diagrams and plans were cooked up by crank inventors.None of them ever put a wormhole in their machines, though.

I’ve heard some cosmologists speculating that equal amounts of “positive” and “negative” mass was created during the Big Bang, and that this violated no conservation of mass/energy laws as long as the total net energy remained 0…

The problem here is that we don’t really know what the signature of a space warp or teleport drive might be, so I don’t know how we would even begin searching for such a thing, even assuming it were possible.

@Eniac

Yes, but at this point you are redefining what we mean by “ambitious”, not saying anything about engineering. The fact is that all civilizations have been based around the use of energy, from the ancient agricultural societies where wealth meant control of farming land and labor to modern society with our power grids and transportation networks.

If by “progress” we mean more of the same, i.e. bigger machines, spaceships, recovery of asteroidal resources, or even just plain old population growth and more agriculture on or beyond the Earth you will unavoidably begin using a bigger fraction of the energy available from the sun and other sources.

If by progress you mean more human self expression through art and books, spiritual progress, or humans throwing down all their weapons and resolving petty disputes via mutual conversation and understanding, than, yeah, those goals are unrelated to greater mastery of materials and energy. And, they are rather inconveniently hard to quantify in physical terms… not everyone may agree that the Great American novel is worthy of the name, but no one can argue over the fact that the great and bountiful 3rd Millennium Solar Empire handles 10^18 watts of power with its great solar conversion arrays. ;-)

But, this IS a blog devoted to interstellar travel and human interstellar travel will certainly require much greater mastery over energy and materials.

Information is one domain where advancement doesn’t seem as tied to energy… but think of the energy required to run computers and the chemical elements needed in their construction, and the energy needed to process said materials. Granted, great advances in computing power have been achieved using much LESS energy and materials than before. ENIAC used far more power and thousands of vacuum tubes and is less powerful than my pocket calculator.

Perhaps future society will measure its advancement by the amount of terabytes of information we through around? Given that it mostly seems to be internet advertisements and porn these days I find it hard to accept this measure as definitive, but it is possible to imagine computer-dominated futures where humans choose to play VR games all day or whatever instead of developing a space based civilizations. This isn’t really a good future from the point of view of those who want to travel to the stars, though.

I am not a transhumanist, I do not think that human society will be utterly transformed by technology into data entities in the next few hundred years or indeed that such a transformation is possible or even desirable. We have had this argument before, so I have no wish to have it again, though.

Even if we can find some way to copy our neural connections onto a disc or whatever, it is a lousy way to travel or achieve immortality. You go nowhere, indeed you experience death if the scanning process is destructive.

The best SF take on mind uploading I’ve seen was in the Canadian TV series Lexx– the Brunnen G’s so-called “Burst of Life”.

“Citizen, you have chosen death… and through it, the gift of eternal life…” -Library Woman

“Eternal life? Um… not exactly. That’s a sales job. It’s just blade, and bone, and blood, friend. You’re going to be nothing but data on a disc that no one will ever care about.” – Poet Man

See episode 2, season 1, “Supernova”. :D

Christopher: “I’ve heard some cosmologists speculating that equal amounts of “positive” and “negative” mass was created during the Big Bang, and that this violated no conservation of mass/energy laws as long as the total net energy remained 0…”

You are perhaps thinking of one of the following:

1. The presence of what we call “matter” and “anti-matter” in unequal quantities is seen as surprising in that there is no known mechanism — though there must be one — to give this outcome from the big bang. When they were done annihilating each other there was left over matter, which is all that we see in the universe.

2. The universe’s gravitational potential energy appears to be equal in magnitude and opposite in sign to all the matter (including dark matter) in the universe. The net is zero. This may be significant since the coincidence (if it turns out to be precisely so) is, well, unlikely.

“The problem here is that we don’t really know what the signature of a space warp or teleport drive might be, so I don’t know how we would even begin searching for such a thing, even assuming it were possible.”

Neither do I, of course. Like many scientific discoveries just be on the lookout for the unusual and unexpected in the normal course of astronomical and astrophysical observations. Unexpected data often spurs the birth of new discoveries.

Ron S: No, by “positive and negative” matter I do not mean matter and antimatter… antiparticles reversed electrical and magnetic properties from normal particles but they have positive mass as far as we know.

I am referring to matter with “negative” gravitational and inertial mass, like in Robert Forward’s hypothetical negative mass propulsion system. Since this negative mass has negative energy, to get rid of it requires energy… and pulling it out of nothingness with an equal amount of positive matter does not violate conservation of energy since the net energy is still zero, leading some cosmologists to suggest that our universe was created this way and split off into positive and negative lobes that split away from each other.

Of course, we have never observed matter that has negative gravitational and inertial properties (like accelerating in the opposite direction to that in which you shoved it!). Maybe it is just a mathematical fiction.

I have read that matter with negative gravitational mass and positive inertial mass would cause problems for General Relativity by destroying the equivalence between inertial fields caused by acceleration and gravity fields- this is why physicists want to “weigh” antiparticles and find out if they fall up or down in a gravity field, and by how much. But the kind with negative gravitational and inertial properties causes no problems with the math, despite having truly bizarre properties.

I agree… often it is the observations that don’t fit our predictions that shows the way to new discoveries. None of our observations have required LGMs (Little Green Men) so far, however, despite the joke about quasars being the exhaust of distant intergalactic photon rockets- but who knows, perhaps someday the signature of a distant alien civilization could be found hidden in the data collected from our astronomical observations.

I still support the idea of searching for solar civilizations utilizing energy on a scale that makes them Kardashev Type-II. Even if future advances in physics give us ways to reach the stars quickly without requiring enormous amounts of energy, there will still be plenty of other activities that call for lots of energy and raw materials. You can’t say for sure that ET won’t build big, and fast interstellar travel would just make it easier to exploit enormous amounts of energy and material resources.

closer to one-hundredth of one percent…

> Explaining earlier searches for Dyson spheres, Kuhn went on to discuss

> how civilizations use power, noting that we use half of one-tenth of one

. ^^^^^^^^^^^^

> percent of the total energy our planet absorbs from the Sun.

Greetings to all,