The image of double suns rising over the planet Tatooine from the first Star Wars movie never quite goes away. I remember watching the film in a theater about a week after its release, being dazzled by the visuals but thinking that a planet in an orbit around both stars of a binary would have to be well outside the habitable zone. I didn’t believe in Tatooine, in other words, though now I’m a bit more circumspect. A couple of years ago Cheongho Han (Chungbuk National University, Korea) wrote a paper suggesting that microlensing might be of use in finding a planet fitting this description, if indeed such a planet exists.

Then yesterday Massimo Marengo dropped me a note about new work he has been involved in that puts a damper on the idea of terrestrial worlds in such settings. Long-time Centauri Dreams readers will remember Marengo, whose fascinating work on Epsilon Eridani we’ve covered in these pages on several previous occasions. Now at Iowa State University, the astrophysicist has been studying tight double-star systems, using data harvested from the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Working with principal investigator Jeremy Drake (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics), Marengo and team are learning that the problem with tight binaries is the chance for planetary collisions. We’re talking about a class of binaries called RS Canum Venaticorums (RS CVns) that are separated by something on the order of 3.2 million kilometers, roughly two percent of the distance between the Earth and the Sun. That produces orbits of just a few days and tidal lock, with each star presenting the same face to the other.

Image: This artist’s concept illustrates a tight pair of stars and a surrounding disk of dust — most likely the shattered remains of planetary smashups. Using NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, the scientists found dusty evidence for such collisions around three sets of stellar twins (a class of stars called RS Canum Venaticorum’s or RS CVns for short). Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Imagine two stars similar to the Sun in size and about as old as the Sun when life first evolved on the Earth. They’re possessed of strong magnetic fields and giant spots, the result of their fast spin, and the magnetic fields, in turn, drive powerful stellar winds that slow the stars and pull them closer together over time. Now things get tricky, for the new work suggests that the gravitational influences of the stellar pair continually change as the stars approach each other, causing planets and other objects circling the stars to experience collisions.

Says Marc Kuchner (NASA GSFC):

“These kinds of systems paint a picture of the late stages in the lives of planetary systems. And it’s a future that’s messy and violent.”

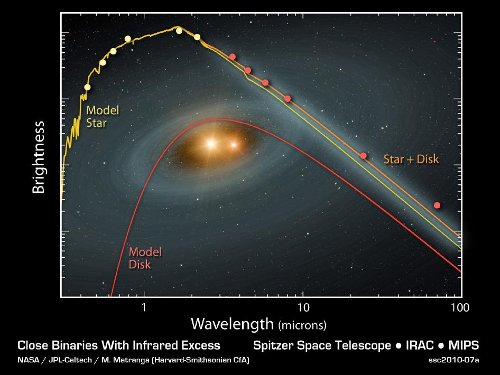

Indeed. And the evidence from Spitzer seems tight. The instrument can see the glow of hot dusky disks around three tight binary systems matching this description. The thinking is that the dust found here would normally have dissipated from stars at this level of maturity. Something, in other words, is causing fresh dust to be created, implying a chaotic process. Planetary collisions are the most likely candidate.

Image: Spitzer’s cameras, which take pictures at different infrared wavelengths, observed the signatures of dust around three close binary systems. Data for one of those systems are shown here in orange. Models for the stars and a surrounding dusty disk are shown in yellow and red, respectively. The disk reveals that some sort of chaotic event — probably a planetary collision — must have generated the dusty disk. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Harvard-Smithsonian CfA.

We know that planets can exist around closely-spaced binaries — a tight eclipsing binary system called HW Virginis, for example, is known to be orbited by two gas giants. But HW Virginis c has a semi-major axis of 3.6 AU, while HW Vir b is at 5.3 AU. Both are well outside the habitable zone of the stars they orbit. In any case, this binary system involves a B-class and an M-class star, not the kind of system depicted in Tatooine or examined in the current work.

With the stars under study, we have more of a When Worlds Collide scenario than anything from Star Wars. Here’s Jeremy Drake on the matter:

“This is real-life science fiction. Our data tell us that planets in these systems might not be so lucky — collisions could be common. It’s theoretically possible that habitable planets could exist around these types of stars, so if there happened to be any life there, it could be doomed.”

Another exoplanet orbiting twin stars is found around the binary PSR B1620-26, but here again, we’re not exactly dealing with Sun-like stars. The planet involved orbits a pulsar and a white dwarf. And back to Cheongho Han for a moment. The scientist believes that if a terrestrial world did exist in a stable orbit around two stars similar to our Sun, the only way to find it would be through microlensing. Radial velocity studies avoid short-period binaries, but the microlensing signature should be detectible. Marengo and Drake’s work suggests that if such a world is found, it may be a rarity indeed.

The paper is Matranga et al., “Close Binaries with Infrared Excess: Destroyers of Worlds?” Astrophysical Journal Letters 720 (August, 2010), L164 (preprint). Cheongho Han’s paper is “Microlensing Search for Planets with Two Simultaneously Rising Suns,” Astrophysical Journal Letters 676, No. 1 (20 March 2008), L53 (abstract).

What about larger stars? (say red giants) Could planetary systems have any chance of surviving (within a habitable zone) with more massive stars? Especially since the habitable zone would be further out?

Also, is anyone working on finding exoplanets around Alpha Centauri?

Darnell, I don’t know the answer to the red giant question, but re Alpha Centauri, the answer is yes — there are three ongoing searches for exoplanets there, and hopes are that we’ll have something definite one way or another within the next few years:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=10489

Tatooine doesn’t need to be the planet to circule BOTH stars.

Is it possible that Tatoonie just circles one sun and the other sun is much bigger but much further away, and just appear to be close in the sky?

A few days ago I found this other article on the effect that the gravitation of the close star would have on the moons of hot Jupiters :

http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2010/08/18/2986337.htm

Simulations see to indicate that they would be stripped off.

I’m sure the Jedi use The Force to keep Tatooine’s orbit stable.

They probably cleared nearby planets out of the way.

More seriously, apparently, Jupiter had something to do with keeping too many comets and asteroids from striking Earth, so I wonder how massive planets, and brown dwarfs, might affect results in a close binary.

Hi Folks;

I can imagine what a beautiful novel vantage point future human settlers and explorers will have, if say, they travel to a two star or a three star system that has at least one Earth like planet in a stable orbit around one of the stars. More specifically, image a tripple system that included a G-2 star like the Sun, a red dwarf, and a deep orange K-class star. Throw in a habitable moon in orbit around a gas giant planet in such a stable orbit, and the view from the surface of the moon could be just plain and simply awesome.

I did a rough mental calculation in my head just now that assumed that one out of every ten stars has a planet that could be habitable or terraformable on average. This works out to be 10 EXP 23 planets in just the visible portion of the universe alone.

Put it this way, imagine the very small end grains of flower such as from a bag of Gold Medal Brand Flower typically sold in super markets here within the United States. I assume that such low end range flower grains are only 100 micrometers accross. Well then, the number of such planets would be equal to the number of such low end flower grains that would completely fill a 100 cubic kilometer volume. Ever take just a pinch of Gold Meadow Flower and through it up into the air and notice the cloud that results which has far too many dust grains to ever count. I do not know about you folks, but I am lucky if I can keep a clear mental image of 10 mentally countable red dots in my mind at the same time.

Put another way, 10 EXP 23 is roughly equal to the number of drops of water within the combined hydrospheric water content on the entire planet Earth, all oceans, lakes, rivers, aquifers, ponds combined.

This boggles my mind. We space-head astronautical, physics, cosmology, and astronomy types are no stranger to dealing with numbers of the order of 10 EXP 23 in an abstract manner, but it is sometimes helpfull to put such numbers in a concretely framed and tangible context. Just as assuredly as there is an esthetic and visceral artistic appeal in trying to grasp huge numbers, that are still only miniscule in comparison to much large numbers such as those referred to as ensembles, the beauty we will discover on other world without end, can only spur us on to advocate for more bold space based observatory platforms for studying exo-planetary systems. The potential number of species of life forms is perhaps even more staggering.

Whether or not double or tripple systems can have planets where such stars orbit each other closely enough is another question, but my guess that that there are probably numerous systems right here in the Milky Way where the stars are far enougnh away from each other such that one star can have planets in stable orbit around it.

Oh, great. Now agents have another reason to reject my novel, which suggests that intelligent life existed at one point on a habitable planet orbiting Algol.

Regarding the HW Virginis system, it has had an interesting history: as an sdB+dM binary, the primary is a post-red giant star, meaning the binary system has undergone mass transfer (primary to secondary), mass loss (from the primary), orbital decay via engulfment of the secondary in the red giant’s envelope (thus creating the sdB star via the rapid mass loss), and is still undergoing slow tidal decay as it gets closer to entering the cataclysmic variable stage. Presumably also the planets themselves accreted some of the matter lost from the star. All this means the planetary system likely looks very different from its original state!

In fact the region where a planet would receive as much radiation from the sdB star in the HW Virginis system as Earth does from the Sun is somewhere around 4-5 AU (the red dwarf contributes very little luminosity), so the outer planet may be in the liquid water zone. Of course, given the system’s history, it is debatable whether this region actually counts as habitable in any meaningful sense of the term.

As something of an expert on RS CVn systems (the subject of my dissertation), I’m less than convinced about the implications for habitable planets drawn from this interesting paper (basically, I’m saying that those implications are being over-hyped). The mass of the system with the best data, II Peg, is too high (and subsequent MS lifetime too short) to make it of much interest in the first place. Secondly, the timescale for rapid orbital period decay of the system is pretty short, less than a billion years, and perhaps much less. It’s not clear that this can destablize orbits much more distant than that of Mercury, for example. Would our solar system be that much different if we had lost Mercury within the first billion years or the first couple of hundred million years? (clearly, if Mercury had collided with Venus, then maybe that’s significant, then again, maybe all the planetesimals produced would have been gone in a period short enough not to matter to life on earth. Remember, life couldn’t really sustain itself on earth until after the end of the Late Heavy Bombardment, at around 3.6 byrs. Also remember that the habitable zone for these systems is going to be roughly 40% further out (II Peg has a much higher mass ratio than most RS CVn sytems). I’m not even that convinced by the dust modelling: we’re told that the dust distribution has a hole that is, within the errors, the same size the radius of the disk has to be to have the correct temperature for the dust grains. Surely, that radius (from temperature modelling) is just some short of average. Thus, to me, it hasn’t been demonstrated that a plausible annulus can even reproduce the observations.

Finally, 3 out of 10 systems had detectable IR excesses. So, at best, I think one can say that maybe, just maybe, the existence of some relatively small fraction of otherwise habitable close binary systems might be in doubt. So, I don’t think lovers of Tatooine need to be overly concerned.

Sorry, I should have mentioned in the above that of MUCH greater concern for habitability in active close binaries is simply that they are ACTIVE and stay that way throughout their mains sequence liftimes (the same problem one has with K and M dwarfs only the habitable zone is obviously moved further out)! II Peg itself has hosted the largest x-ray and gamma ray flare yet seen from a stellar system (saturated the SWIFT detectors). Without looking it up, I seem to recall it was about a million times more luminous than ANY flare every observed on the sun. Thus to construct a habitable close binary system you need to put the stars far enough apart that they’re not tidally locked (so they won’t remain fast rotators throughout their lives, so you need periods typically greater than 14 days or so) and balance that with their luminosities and masses to get a habitable zone that can be gravitationally stable.

ok, I didn’t understand all of this cause I’m not an astronomer and english is not my language. So, from what I understand, life in a system with two close suns would be impossible because the orbit of the planets would be unstable right ? Therefore, a planet like Tatooine and its suns isn’t likely to exist in real life.

Monyka, you’re right — this particular work suggests that planets orbiting two closely-spaced stars, as in ‘Tatooine’ from ‘Star Wars,’ would be inherently unstable. The suggestion is that when you get too close to the stellar pair (i.e., into a region that would be habitable on a planet there), the orbit of the planet would be too unstable to survive, and the risk of planetary collision high.