New Horizons’ encounter with Pluto/Charon in 2015 is eagerly anticipated, but let’s not forget that the spacecraft will be operational afterwards as it moves deeper into the Kuiper Belt. Fuel will be tight, but there should be enough available for one and possibly a second encounter with a Kuiper Belt Object (KBO), assuming we can identify a likely candidate. I’m often asked how such targets would be chosen, and here’s one answer: A new site called IceHunters has been set up at Southern Illinois University that will draw the public into the hunt for icy objects.

At the heart of the IceHunters project are images made by some of the world’s largest telescopes (most come from the 6.5-meter Magellan telescope in Chile and the 8-meter Subaru telescope on Mauna Kea), of the region where potential targets will be found. Like SETI@Home, IceHunters leverages widely distributed PCs in the hands of end-users worldwide. Check the site and you’ll see that instead of conventional astronomical images, you’re looking at ‘difference images’ — produced by subtracting two images as a way of removing non-moving objects like stars and galaxies. Of course, these objects actually are moving in their own right, but the method should help Kuiper Belt objects and asteroids stand apart from the pack.

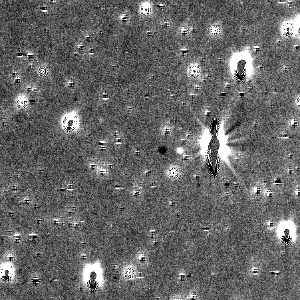

Images like these play havoc with computers but a critical human eye can, with skill, pick out unknown objects. KBOs and asteroids can be marked by anyone with an up to date Web browser. Pairs of images taken at different time intervals are subtracted from each other, but as the image shows, it’s impossible to equalize the appearance of the stars perfectly before the subtraction process occurs. As a result, we wind up with blotches and other odd marks where star residuals are found.

Image: To make the pesky stars disappear the two images are subtracted from one another. This doesn’t make the stars go entirely away. Even with the blurring step, the two images aren’t exactly identically and instead of having 1-1 = 0, we have something more like 1.01432 – 1 is not 0. Where the first image was brighter, a bit of white shows in the image. Where the second image was brighter, there is a bit of black. The KBO stands out in this image as both a dark blob (from being in the second image) and a white blob (from being in the first image). Credit: IceHunters.org.

It’s amazing to realize as we embark on this search that other than Pluto, the first Kuiper Belt Object wasn’t discovered until 1992. That was the work of Dave Jewitt and Jane Luu at the University of Hawaii, who discovered the object designated 1992QB1 at about 40 AU from the Sun. Although the Kuiper Belt is one of the least mapped regions of our system, we’ve now found more than 1,000 objects beyond Neptune’s orbit, and current estimates are that as many as half a million KBOs larger than 30 kilometers or so in diameter are lurking out at system’s edge.

IceHunters images are drawn from a roughly 2-square degree field in Sagittarius, chosen because objects here would have the potential to be near New Horizons’ trajectory after its 2015 encounter with Pluto/Charon. The KBOs discovered will be collected into a catalogue and published with the name of their discoverers, another chance for citizen scientists to make a tangible mark in their field.

“Projects like this make the public part of modern space exploration,” says SIUE assistant research professor Pamela Gay. “The New Horizons mission was launched knowing we’d have to discover the object it would visit after Pluto. Now is the time to make that discovery, and thanks to IceHunters, anyone can be that discoverer.”

The first KBO chosen as a target won’t be selected until just before the encounter with Pluto/Charon, but the hope is to identify a KBO at least 50 kilometers across. The procedure for this encounter would roughly parallel what happens at Pluto. The spacecraft will be making global maps of Pluto and Charon at various wavelengths and taking high-resolution images to study the surface composition of these objects. New Horizons will pass within 12,500 kilometers of Pluto itself (29,000 kilometers from Charon) and will see Plutonian features as small as 100 meters across.

Much of the work will continue even as the spacecraft passes Pluto, looking back to take atmospheric measurements as New Horizons moves into the shadows of Pluto and its largest moon. Assuming all goes well, the Pluto/Charon encounter might be a warmup for the second or even third flyby of a KBO. Getting the eyes of the public on IceHunter’s ground-based images may uncover the identity of the spacecraft’s targets as they move through the vast stellar background. In any case, it’s a way of doing good science to build up a broader picture of the Kuiper Belt population.

I’m in! Already found (?) a few. I encourage all other CentDr readers to join me. Got a few spare minutes? Perhaps find the KBO that Horizons visits. Oh the kudos!

This is a dream come true! Once I’m at the site doing this, I can’t get off! I hope it will eventually be expanded to further regions of the Kuiper Belt to enable us to take part in searching for KBOs of Pluto’s size and even bigger!

What a great site. I have tagged 59 objects so far. It’s amazing after about ten finds you can really spot the KBOs right away. I’m enjoying being an amateur scientist again, and this time there are no messy test tubes or chemicals or bulky telescopes to lug out into the field. I hope to be able to name the KBO I discover this way. I’d probably name it after my cat, Pocatello.

Past the Kuiper Belt may be a long dead white dwarf companion to the Sun. If it existed, while it was a red giant it would have been hot enough to produce oceans on Mars. Any gas giant planet in orbit of it would be easier to spot than a cold white dwarf only illuminated by the Sun. The IBEX neutral atom imaging experiment has given evidence for a strong magnetic field outside the Sun’s magnetosphere, which would fit a long dead white dwarf star twin to the Sun nicely. Such a twin would clear out most objects past the Kuiper Belt, and Eris may have once been in orbit of a more massive twin to the Sun, captured by the Sun after the red giant lost too much mass.

Richard A Laughlin: re: IBEX. Please give a reference; I would like to read it.

re:IBEX

I found:

http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/ibex/index.html

and

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interstellar_Boundary_Explorer