Paging back through Kelvin Long’s book Deep Space Propulsion (Springer, 2011) last night, I was reminded that Freeman Dyson had written about his disillusionment with nuclear pulse propulsion methods long after Project Orion was terminated. The passage is in his autobiographical account Disturbing the Universe (Basic, 1981), which caught Long’s attention and led him to reprint it. Here’s a snippet of Dyson’s reflections:

Sometimes I am asked by friends who shared the joys and sorrows of Orion whether I would revise the project if by some miracle the necessary funds were suddenly to become available. The answer is an emphatic no… By its very nature, the Orion ship is a filthy creature and leaves its radioactive mess behind it wherever it goes… Many things that were acceptable in 1958 are no longer acceptable today. My own standards have changed, too. History has passed Orion by. There will be no going back.

Long speculates that Dyson may simply have been referring to Orion as an Earth-launch vehicle, leaving open options for construction and deployment in deep space, but my own sense is that the passage above means just what it says. When I interviewed Dyson for Centauri Dreams (the book) back in 2003, he made it abundantly clear that he considered the matter closed. He criticized nuclear methods because they could use no more than one percent of the mass with any nuclear reaction, and said he was much more enthusiastic about laser and microwave beaming and pellet propulsion concepts like those first developed by Clifford Singer back in the ‘70s and later expanded significantly by Gerald Nordley.

Interstellar Flight in the Public Eye

Long covers the Orion concept in detail as well as Medusa, a remarkable attempt to fuse pulsed propulsion with sail technologies (we need to talk more about Medusa soon). But I was really digging into his book in relation to Robert Bussard, whose 1960 paper “Galactic Matter and Interstellar Flight” (citation below) is in my view the real marker for the emergence of interstellar studies. To be sure, there were key papers before this, including the significant contributions of Leslie Shepherd and Eugen Sänger, both of whom I want to talk about in coming days. But what you get with Bussard is an idea published in an academic journal that is found and brought emphatically into the public consciousness in ways that transform public thinking.

If the beauty of beamed propulsion is that it removes the need to carry huge stores of propellant, the advantage of Bussard’s ramjet concept was that it harvested what it needed from the medium. Bussard announced his intention to speed up interstellar travel times enormously:

… by abandoning the interstellar rocket entirely, turning to the concept of an interstellar vehicle which does not carry any of the nuclear fuel or propellant mass needed for propulsion, but makes use of the matter spread diffusely throughout our galaxy for these purposes. By rough analogy with its atmospheric counterpart we call this an interstellar ramjet. Other possible types might include, vehicles which carry all of the nuclear fuel on board and only use swept-up galactic matter as inert diluent added to the propellant stream analogous to the operation of ducted rockets in atmospheric ?ight and all variations between these two extremes. Study of the performance of these fuel-carrying vehicles is deferred to a future paper.

To my knowledge, Bussard never wrote this future paper — if I’m wrong about that, I hope someone will correct me. His ideas, of course, generated an influx of new concepts tweaking the ramjet and taking the idea of matter collection in deep space in entirely new directions.

We’ve looked at problems with the original Bussard design in these pages before, focusing especially on the proton/proton fusion reaction and the power needed to exploit it. A number of theorists have suggested workarounds, including Centauri Dreams regular Al Jackson, who in several papers explored a laser-powered ramjet design that I want to talk about next week. For today, though, the focus is on reaction to the Bussard paper of 1960, for it was quickly seized upon by science fiction writers and scientists alike. The book Intelligent Life in the Universe, co-authored by Carl Sagan and Iosif S. Shklovskii, focused on time dilation at relativistic velocities and the way to the stars seemed to open.

Time Dilation Takes Center Stage

Intelligent Life in the Universe came out in 1966, a greatly expanded version of Shklovskii’s original Russian text of 1962. It is the coupling of relativistic time dilation and the Bussard ramjet idea that seized the imagination of science fiction writers. Sagan and Shklovskii could show that at an acceleration of 1 g, only a few years (ship-time) is required to reach the nearest stars, while (as experienced again aboard the ship) only 21 years takes you to the galactic center, and 28 years to the Andromeda galaxy. There being no time dilation on the home planet, the elapsed time there as the star mission proceeds, for distances beyond about 10 light years, roughly equals the distance of the destination in light years. In other words:

…for a round-trip with a several-year stopover to the nearest stars, the elapsed time on Earth would be a few decades; to Deneb, a few centuries; to the Vela cloud complex, a few millennia; to the Galactic center, a few tens of thousands of years; to M 31, the great galaxy in Andromeda, a few million years; to the Virgo cluster of galaxies, a few tens of millions of years; and to the immensely distant Coma cluster of galaxies, a few hundreds of millions of years. Nevertheless, each of these enormous journeys could be performed within the lifetimes of a human crew, because of time dilation on board the spacecraft.

Einsteinian time dilation had been considered long before this, of course, and it shows up in science fiction in early stories like Robert H. Wilson’s “Out Around Rigel,” which ran in Astounding Stories in December of 1931. But when Sagan and Shklovskii combined time dilation with a serious discussion of communications between galactic civilizations as enabled by Bussard-style ramjets, the notion went from utterly theoretical to a matter that mixed science with engineering. Bussard’s ideas went on to inspire a wave of ramjet-related studies, as we’ve already seen, and also inadvertently triggered the study of magnetic sails as braking devices.

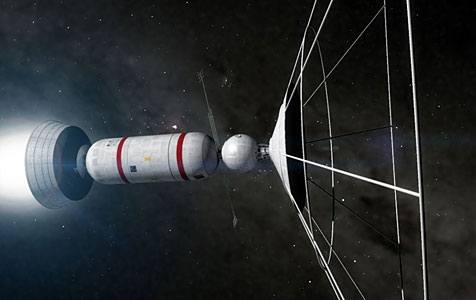

Image: The Bussard ramjet, which opened serious speculation about attaining speeds close to c. Credit: Adrian Mann.

The Ramjet in Science Fiction

Meanwhile, we can think about the later science fiction that flowed from the Bussard ramjet. I usually cite Poul Anderson’s Tau Zero in that regard, a 1970 novel that grew out of a 1967 short story (“To Outlive Eternity,” which ran in Galaxy a year after Sagan and Shklovskii). But we can add to Anderson’s tale of a runaway starship the work of Larry Niven, who described Bussard vessels in his 1976 novel A World Out of Time:

The starships were Bussard ramjets. They caught interstellar hydrogen in immaterial nets of electromagnetic force, compressed and guided it into a ring of pinched force fields, and there burned it in fusion fire. Potentially there was no limit at all on the speed of a Bussard ramjet. The ships were enormously powerful, enormously complex, enormously expensive.

I pulled this quote from Technovelgy.com, which routinely looks at the intersection of science and science fiction. The first part of Niven’s novel appeared in Galaxy in 1971 as a short story called “Rammer,” another indication that Bussard’s notions were quickly embraced. Gregory Benford uses a greatly modified Bussard design in his Galactic Center novels, dodging the proton-proton fusion problem in well-vetted ways we’ll discuss next week. Sagan went on to refer to the ramjet in the popular television series Cosmos and the book that accompanied it, but the ultimate sign of Bussard’s ideas reaching full public awareness may have been the ‘Bussard collector’ used in the Star Trek universe as part of StarFleet’s propulsion paraphernalia.

It could be argued that much was coming together anyway by the early 1960s, and two years after Bussard described the ramjet, Robert Forward would put the idea of a laser-propelled lightsail into the public consciousness in an article in Missiles and Rockets. But I’ll give the nod to Robert Bussard, with a major assist from Sagan and Shklovskii, for turning the interstellar idea into public currency by suggesting that although the engineering was far beyond our skills, the basic physics did not rule out human travel to the stars. And if you’re a science fiction writer with a need to get around the galaxy quickly, Bussard will always be a contender.

The Bussard paper is “Galactic Matter and Interstellar Flight,” Astronautica Acta Vol. 6 (1960), pp. 179–94 (available online).

The Bussard collector idea was introduced in Star Trek: The Next Generation thanks to series illustrator/technical consultant Rick Sternbach, who’d worked with Bussard on an earlier project and did paintings of a Bussard ramjet and other things for Sagan’s Cosmos.

I used a ramjet in my first published story, “Aggravated Vehicular Genocide,” and as the title suggests, the story explored a potential hazard of relativistic travel. More recently I’ve been working on expanding the story into a novel and have replaced the ramjet with what I think is a more plausible microsail drive whose inspiration came from this site and its namesake book.

Paul

I think you are right , Intelligent Life in the Universe was the popular literature to have a ‘wide’ recognition of interstellar life. I say ‘wide’ because even then it was not a huge subset of the intelligent laymen.

Visual entertainment media usually is the best attention getter. I think the first use of interstellar flight in a movie must have been This Island Earth 1955, tho there it is a goofy mess (poor Raymond F. Jones!). Next year Forbidden Planet, 1956, got it right, I have been told that either one of the two story guys, or screenwriters really knew his SF stuff. Alas it’s kind of subtle in the film so I am sure went by 98% of the audience.

Funny inn 1966 Gene Roddenberry , who knew his SF stuff too, thrust it into the faces of the TV audience, and maybe , just maybe, some small fraction of the laymen become aware. I am not sure how many of the unwashed still know what it means.

Lost in Space used to drive Asimov into rage over it’s ignorance of what interstellar and interplanetary flight… alas, in some ways that still continues.

I note that , maybe, Eugen Saenger was the first to note what a 1g ship would mean for interstellar flight.

Tho some engineers in the early 50’s had noted it , including our grand master Robert Heinlein.

News flash !

(Phys.org) — Fifteen years of work by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s National Ignition Facility (NIF) team paid off on July 5 with a historic record-breaking laser shot. The NIF laser system of 192 beams delivered more than 500 trillion watts (terawatts or TW) of peak power and 1.85 megajoules (MJ) of ultraviolet laser light to its target. Five hundred terawatts is 1,000 times more power than the United States uses at any instant in time, and 1.85 megajoules of energy is about 100 times what any other laser regularly produces today.

The shot validated NIF’s most challenging laser performance specifications set in the late 1990s when scientists were planning the world’s most energetic laser facility. Combining extreme levels of energy and peak power on a target in the NIF is a critical requirement for achieving one of physics’ grand challenges — igniting hydrogen fusion fuel in the laboratory and producing more energy than that supplied to the target.

In the historic test, NIF’s 192 lasers fired within a few trillionths of a second of each other onto a 2-millimeter-diameter target. The total energy matched the amount requested by shot managers to within better than 1 percent. Additionally, the beam-to-beam uniformity was within 1 percent, making NIF not only the highest energy laser of its kind but the most precise and reproducible. “NIF is becoming everything scientists planned when it was conceived over two decades ago,” NIF Director Edward Moses said. “It is fully operational, and scientists are taking important steps toward achieving ignition and providing experimental access to user communities for national security, basic science and the quest for clean fusion energy.”

The user community agrees. “The 500 TW shot is an extraordinary accomplishment by the NIF Team, creating unprecedented conditions in the laboratory that hitherto only existed deep in stellar interiors,” said Dr. Richard Petrasso, senior research scientist and division head of high energy density physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “For scientists across the nation and the world who, like ourselves, are actively pursuing fundamental science under extreme conditions and the goal of laboratory fusion ignition, this is a remarkable and exciting achievement.”

“Already the most incredibly tightly controlled and most energetic laser in the world, it is remarkable that NIF has achieved the 500 TW milestone – quite a significant achievement,” said Dr. Raymond Jeanloz, professor of astronomy and earth and planetary science at the University of California, Berkeley. “This breakthrough will give us incredible new opportunities in studying materials at extreme conditions.”

NIF is operating routinely at unprecedented performance levels. The July 5 shot was the third experiment in which total energy exceeded 1.8 MJ on the target. On July 3 scientists achieved the highest energy laser shot ever fired, with more than 1.89 MJ delivered to the target at a peak power of 423 TW. A shot on March 15 set the stage for the July 5 experiment by delivering 1.8 MJ for the first time with a peak power of 411 TW.

Original concerns about achieving these levels of extreme laser performance on NIF centered in part on the quality of optics existing in the late 1990s that could not withstand this intense laser light. Lawrence Livermore researchers worked closely with their industrial partners to improve manufacturing methods and drastically reduce the number of defects. Livermore scientists also developed in-house procedures to remove and mitigate small amounts of damage resulting from repeated laser firings.

NIF is influencing the design of new giant laser facilities being built or planned in the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Japan and China.

@ A. A. Jackson: The original pilot of Lost in Space handled interstellar flight better than the series, since the idea there was that the ship would take 98 years to reach Alpha Centauri (although they claimed the ship would be traveling at nearly lightspeed), which was why the crew needed to be in suspended animation. But when they added Dr. Smith as a stowaway and didn’t have any spare cryotubes, they had to reduce the interstellar travel time. There was a lip-service reference in the revised pilot to an experimental hyperdrive being activated, but this was largely ignored later in the series.

When hypothesizing about distances covered by years of one-gee acceleration, Sagan’s speculations glossed over the immense power needed, but even worse he ignored the incredible shielding required to endure impacts when the dilation factor is a million. At that speed a one milligram impactor would seem like a small nuke.

Impacts are not the worst of it. The interstellar gas, while not dense enough to make a ramjet work, is unfortunately dense enough to incinerate anything attempting to travel at near-relativistic velocities. Forget about gamma factors.

It is sad, but this is just another one of these flights of fancy that have been put a stop to by reality, like Moon-people and Martians…