by Larry Klaes

It’s been a tough weekend, not only with the loss of the SpaceX Falcon booster but also the NanoSail-D sail experiment that flew aboard it. I’ll have more on the loss of the sail tomorrow, but this may be a good day to look back and reflect on some of the titans of astronomical history, including the Hale instrument whose views of the heavens gave so many of us early inspiration. Tau Zero journalist Larry Klaes has been pondering these matters, and offers us a look at some of the people and instruments that proved essential in changing our view of the universe.

Sixty years ago, on June 3, 1948, the most massive astronomical tool of the era was dedicated on Palomar Mountain near Pasadena, California. Known as the Hale Telescope, this instrument was much bigger than any telescope that had ever come before it. In its nearly three decades as the reigning largest telescope on Earth, the “Giant Eye” of the Palomar Observatory revealed new vistas of the heavens ranging from nearby worlds in our Solar System to the most distant galaxies billions of light years away.

The key to the scientific success of the Hale reflector telescope was its main mirror, which was made by Corning Glass Works (now known as Corning Incorporated) in Corning, New York, using their new Pyrex glass that was stronger and more flexible than other types of similar material. Such a material was necessary, as the initial mirror design was 200 inches (16.6 feet) across, 26 inches thick, and weighed 20 tons.

Image (click to enlarge): Palomar Observatory on what appears to be a fine night for viewing. Note Orion just above the trees. Credit: Scott Kardel.

Corning built two such mirrors at its glass factory in 1934 (the first one, a flawed piece later used for testing, is still on display in the company museum) and shipped it out to Pasadena on a slow-moving train. During its two-week journey across the country, huge crowds all along the delivery route came out to see the monster mirror. In Buffalo and several other major cities that the mirror passed through, the local police were called to control the throngs of people who massed around the special train.

A combination of the years it took to polish the mirror to its nearly flawless finish, the subsequent intervention of World War Two, and other factors kept the Hale Telescope from going into full operation until the year after its public dedication in 1948. The giant instrument retains yet another connection to Central New York, for it is now operated by a consortium of Cornell University, Caltech, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

For an interesting look at the Hale Telescope, check out Palomar Skies. This site contains news, history, and beautiful images of Palomar Observatory written by Palomar public affairs coordinator Scott Kardel.

This year marks another important and much older telescope anniversary, one that essentially made the device housed inside that large white art deco dome on Palomar Mountain and every other telescope before and after it possible: The first definitive description (via a patent application) of a telescope.

The idea of magnifying objects using lenses and mirrors made of glass, quartz, and other substances goes back to ancient times. Reading glasses, or spectacles, were made during the Middle Ages to help people with poor or failing eyesight. One century before the telescope was “officially” recognized, Leonardo da Vinci described in his famous notebooks how a combination of lenses and mirrors would help one “to see the Moon enlarged… and …in order to observe the nature of the planets, open the roof and bring the image of a single planet onto the base of a concave mirror. The image of the planet reflected by the base will show the surface of the planet much magnified.” Whether da Vinci ever actually built and utilized what he wrote about in 1508 is a subject of dispute among historians.

There were others throughout Europe and the Middle East who also described what might be called a telescope during this era, but it was the Dutch spectacle maker named Hans Lippershey who applied for a patent on the telescope on September 25, 1608. Although Lippershey was not granted the patent, he was paid well for the invention by the Dutch government, which was focused on the telescope’s military and commercial applications.

Image: Hans Lippershey (1570-1619), the first to apply for a patent on a telescope design, and possibly the inventor of the first practical refracting instrument.

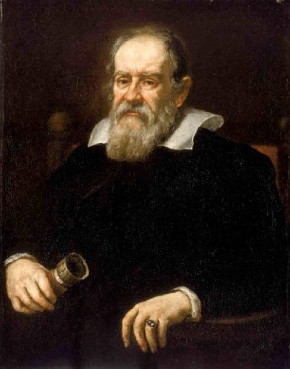

Within months of the announcement of this new observing instrument, telescopes were being made across Europe. Among the scientists of the era who were interested in the astronomical possibilities of the telescope, the most famous of them was Galileo Galilei.

Dissatisfied with the rather crude instruments made in his day, the Italian astronomer constructed his own telescopes, which he began using in 1609 to start a revolution in humanity’s understanding of the Cosmos. Being one of the first scientists to aim his telescopes at the heavens, Galileo saw that Earth’s Moon was not a smooth, polished sphere as once believed, but a cratered, mountainous place: An actual world much like our planet.

When Galileo observed the planet Jupiter in January of 1610, he saw four small “stars” moving around the gas giant globe. These points of light turned out to be the four largest of Jupiter’s moons – Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto – which were later dubbed the Galilean satellites in the astronomer’s honor. Not only were the satellites the first bodies known to circle a world besides Earth, this discovery gave weight to the theory of Nicholas Copernicus, who had declared nearly two centuries earlier that Earth and the other worlds of the Solar System orbited the Sun, rather than everything in the Universe circling our planet, as was long believed.

Image: Galileo Galilei, in a portrait by Justus Sustermans (1597-1681), ca. 1639.

These innovations by Galileo and his contemporaries forever changed the way humanity looked at the Universe and our place in it. As telescope technology improved, astronomers gained even more evidence that our world was neither the center of existence nor the lowest of all places in the Cosmos, but just one of many worlds in a Universe full of stars and planets collected into immense cosmic islands called galaxies.

Although we now have instruments much larger than the Hale Telescope and sophisticated satellite telescopes exploring the heavens beyond the blurring confines of Earth’s atmosphere, the basic design and purpose of all telescopes has remained the same since a Dutch spectacle maker built the first models, an Italian scientist aimed his own optical tubes at the sky, and a far-seeing astronomer made some of the largest telescopes of the Twentieth Century possible. The role of these instruments in enhancing our understanding is nowhere near the end of its journey.

http://www.congrex.nl/08a07/

400 Years of Astronomical Telescopes:

A Review of History, Science and Technology

29 September – 2 October 2008

ESA/ESTEC

Noordwijk, The Netherlands

INTRODUCTION

The meeting will celebrate the 400th anniversary of Hans Lipperhey’s

patent application on 25 September 1608 for the “spy glasses”, the

optical system that became the basis for optical astronomical

telescopes. The meeting will cover the history of the telescope

making and usage, key technologies, and political as well as

sociological aspects.

The program covers all types of telescopes across (and even beyond)

the entire electromagnetic spectrum. The 3.5 day program consists

exclusively of review talks given by invited speakers who have been

working in or even shaped the field.

TARGET AUDIENCE

The target audience is as wide as the topic of this conference, and

includes astronomers who want to broaden their knowledge of telescopes,

people interested in the evolution of this significant part of modern

sciences, technically interested historians, amateur astronomers, and

the interested public. The number of participants is limited to 250

people and early registration is recommended.

TOPICS

o History of optical telescopes

(the early inventions, Galilei, Newton, Herschel, Lord Rosse, 19th

century refractors, the large ground-based facilities, and the history

of optical instruments)

o History of non-optical telescopes

(the history of radio, infrared, X-ray, Gamma-ray and imaging TeV

telescopes as well as telescopes for solar and neutrino astronomy)

o Miscellaneous topics

(the history of astronomical discoveries, amateur telescopes, the

historical driver to do astrometry, and the most famous example of

the Hubble Space Telescope)

o Telescope technologies

(mirror casting and polishing, active optics, telescope mounts and

domes, adaptive optics and interferometry, and the technologies of

radio, sub-mm, X-ray and Gamma-ray telescopes)

o Political and Sociological aspects

(a scientometric look at astronomy, the development of the Europe’s

main ground-based observatory, the challenge of managing big

astronomical projects, NASA’s four great observatories, sacred

mountains, climate change, light pollution and astronomy in 3rd

world countries)

o The Future

(future telescope and instrument technologies, visions for new

telescopes, challenges and perspectives for future generations of

astronomers)

BBC 9/16/08:

“Controversy over telescope origin”

“New evidence suggests the telescope may have been invented in Spain, not

the Netherlands or Italy as has previously been assumed.”

More:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/low/science/nature/7617426.stm

October 6, 2008

Book Review: The Haunted Observatory

Written by Mark Mortimer

The Haunted Observatory

Curious and curiouser things began happening when telescopes opened up to the skies. Richard Baum’s book entitled “The Haunted Observatory – Curiosities from the Astronomer’s Cabinet” has the reader thinking like Alice might have in her wonderland. Bright lights, aspiring dots, gleaming trails of a forgotten impression can all fool a mind into perceiving reality where none may exist. Thus, when it comes to making reason out of the unexpected, some astronomer’s lives get so entertaining and worthwhile and ends up making this book so entertaining.

In the seventeenth century, Galileo built his own telescope, viewed moons and rebuilt our perception of the universe. Jumping off from this, telescopes came into ever more common usage so that by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it seemed like everyone and their brother’s uncle had one and was getting excited about what they saw. With the increasing number of observers, some odd things were seen or at least imagined. Perhaps the sights were real events or perhaps they were dust on a lens. In any case, sometimes different people provided different interpretations, thus leading to vibrant discord. Such discord is the resonance of this book as it looks at how some disagreements were solved and how some remain to be solved.

Full review here:

http://www.universetoday.com/2008/10/06/book-review-the-haunted-observatory/

“THE JOURNEY TO PALOMAR” AIRS ON NATIONAL TELEVISION (ON CAMPUS)

Beginning November 10, PBS will broadcast the documentary film “The

Journey to Palomar” on stations across the country. The program will

air on KCET in the Los Angeles area at 9 p.m. on November 15. For

other listings, click here[1]. “The Journey to Palomar” traces the

personal and professional struggle of George Ellery Hale to build

the greatest telescopes of the early 20th century at the Yerkes and

Mount Wilson Observatories, and finally his 20-year effort to build

the 200-inch telescope on Palomar Mountain, which is operated by

Caltech. Hale also participated in the creation of the Huntington

Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, helped design the

Civic Center in downtown Pasadena, and–perhaps his single greatest

achievement–set the course for the development of Pasadena’s Throop

University into the California Institute of Technology.

The documentary, which was produced, written, and directed by Robin

and Todd Mason, includes archival footage and interviews with some

of America’s top historians and scientists, including two from

Caltech: Steele Family Professor of Astronomy Richard Ellis, and

David Baltimore, president emeritus, Nobel laureate, and Millikan

Professor of Biology.

For more on the film, go to http://www.journeytopalomar.org[2].

[1] http://www.pbs.org/thejourneytopalomar

[2] http://www.journeytopalomar.org

Review of “The Long Route to the Invention of the Telescope”…

Posted by nickpelling on Nov 16th, 2008

Equal parts brilliant and frustrating, Rolf Willach’s “The Long Route to the Invention of the Telescope” (2008), which reprises his featured sessions at the September 2008 conference in Middelburg, is a book formed of two stunningly different halves.

Through his insightful and breathtakingly meticulous analysis in the first seven chapters, Willach dramatically reconstructs the history of optical craft in the centuries preceding the invention of the telescope. Simply put, by casting the development of optics in terms of the technological and craft-based elements in making glass objects, he has produced without any doubt the most important new writing on the subject in decades.

However, in chapters eight to eleven, his obvious eagerness to build on his main findings to retell the history of the telescope leads him to make what seem to me to be terribly, terribly weak inferences. Yet if that were to cause historians to look askance at his whole work, it would be a terrible shame, for there is a huge amount to be proud of here.

Willach is an independent scholar with his very own tightly-focused research programme: applying quantitative scientific testing methodologies to old lens-like objects to try to understand the ways in which they were made. Over many years in dogged pursuit of this quest, he has examined the Nimrud Lens, the Lothar crystal, lapides ad legendum (reading stones) embedded in liturgical art, curved glass covers in reliquaries, spectacle lenses embedded in a bookcase, rivet spectacles found beneath a nuns’ choir, spectacles in private collections, early telescope lenses etc.

Furthermore, there seems to be no end to the range of physical and optical tests he has at his disposal: and he has even built and used his own a replica lens grinding machine. He has also delved deeply into the practical chemistry, physics and craft of glassmaking and glassblowing. In short, in a world where many self-professed experts are content to simply talk a good talk, it is wonderfully refreshing to find someone who has really, really walked the walk.

For Willach, the physical evidence strongly indicates that spectacle lenses developed not out of reading stones (pieces of rock crystal hand-turned on a wheel but progressively more curved towards the edges), but from the large number of reliquary covers needed to accommodate the tidal wave of martyrs’ relics that washed back into Europe after the Crusades. Just as with the reading stones, these were formed from pieces of rock crystal, and individually ground and polished on some kind of wheel, just as similar items had been turned since antiquity.

Full article here:

http://www.ciphermysteries.com/2008/11/16/review-of-the-long-route-to-the-invention-of-the-telescope

“Looking Through Galileo¹s Eyes”

“In 1609, exactly four centuries ago, Galileo revolutionised humankind’s understanding of our position in the Universe when he used a telescope for the first time to study the heavens, which saw him sketching radical new views of the moon and discovering the satellites orbiting Jupiter.”

In synch with the International Year of Astronomy (IYA), which marks the 400th anniversary of Galileo’s discoveries, a group of astronomers and curators from the Arcetri Observatory and the Institute and Museum of the History of Science, both in Florence, Italy, are recreating the kind of telescope and conditions that led to Galileo’s world-changing observations, reports January’s Physics World.”

Full article here:

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/01/090108082902.htm

Thomas Harriot A Telescopic Astronomer Before Galileo

Thomas Harriot

by Staff Writers

London UK (SPX) Jan 15, 2009

This year the world celebrates the International Year of Astronomy (IYA2009), marking the 400th anniversary of the first drawings of celestial objects through a telescope. This first has long been attributed to Galileo Galilei, the Italian who went on to play a leading role in the 17th century scientific revolution.

But astronomers and historians in the UK are keen to promote a lesser-known figure, English polymath Thomas Harriot, who made the first drawing of the Moon through a telescope several months earlier, in July 1609.

In a paper to be published in Astronomy and Geophysics, the journal of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), historian Dr Allan Chapman of the University of Oxford explains how Harriot not only preceded Galileo but went on to make maps of the Moon’s surface that would not be bettered for decades.

Full article here:

http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/Thomas_Harriot_A_Telescopic_Astronomer_Before_Galileo_999.html

Comment: Why we must save our astronomical heritage

16 January 2009 by Clive Ruggles

Magazine issue 2691.

THE Acropolis in Athens, the elaborate temples of Angkor in Cambodia, and the stone statues of tiny Easter Island, home for 1000 years to the most isolated human community on Earth. These are among the 878 World Heritage Sites (both cultural and natural) protected by UNESCO as places of “outstanding universal value” to humankind. As such, each contains extraordinary creative masterpieces from lost cultural traditions. And each represents a vestige of the past that stands out as a powerful source of inspiration to people across the planet.

Yet one aspect of our cultural heritage – astronomy – is woefully under-represented on the World Heritage List. To those of us in the modern, lit-up world, the first time that we see a truly dark night sky can be breathtaking. But until relatively recently, most people experienced this spectacle every clear night, wherever they lived. If we want to appreciate the beliefs and practices reflected in the architecture of ancient temples and tombs, we cannot ignore their relationship to the sky.

The World Heritage List does contain a few ancient sites and monuments with links to the sky, but these were selected because of their broader archaeological and cultural significance. They include the Neolithic passage tomb of Newgrange in Ireland, aligned so the sun shines in only for a few minutes after sunrise on the shortest days of the year. This shows that people 5000 years ago saw a link between ancestors and the sun.

There’s also Stonehenge in Wiltshire, UK, with its well-known connection to midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset; Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, featuring the Fajada Butte “sun dagger” that splits a spiral carving at noon on the summer solstice; and several pre-Columbian sites in Mexico, including Chichen Itza, Monte Alban and Palenque. The Mesoamerican preoccupation with solar, lunar and planetary cycles and conjunctions is manifested in inscriptions, alignments, and the existence of “zenith tubes” down which the light of the sun shone at noon on the two days in the year when it passed vertically overhead.

Despite these examples, there have never been any clear guidelines for nominating World Heritage Sites based on their relationship to astronomy, and this leaves many key sites vulnerable to neglect and irreversible damage. To try and fix this, UNESCO is now encouraging member states to put forward astronomical nominations, and the International Astronomical Union (IAU) will be working with UNESCO throughout 2009 to come up with clear criteria for judging the merits of these sites. It is a fitting task for the International Year of Astronomy, which celebrates the 400th anniversary of Galileo’s first use of a telescope to gain an unprecedented view of the sky.

Full article here:

http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20126915.700-comment-why-we-must-save-our-astronomical-heritage.html

MSNBC /Reuters 1/22/09: “Galileo may get eyes checked posthumously”

“Italian and British scientists want to exhume the body of 16th century astronomer Galileo for DNA tests to determine if his severe vision problems may have affected some of his findings.

The scientists told Reuters on Thursday that DNA tests would help answer some unresolved questions about the health of the man known as the father of astronomy, whom the Vatican condemned for teaching that the earth revolves around the sun.

‘If we knew exactly what was wrong with his eyes we could use computer models to recreate what he saw in his telescope,’ said Paolo Galluzzi, director of the Museum of History and Science in Florence, the city where Galileo is buried.”

Full article here:

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/28791775/

Collier’s magazine, which became famous to space buffs for

publishing articles on Wernher von Braun’s future space plans

illustrated by Chesley Bonestell in the 1950s, also published

a great article with beautiful photographs taken by and of the

200-inch Hale Observatory when it officially opened for

business in 1949.

The full issue, plus some ads, have been scanned in online

at this Web site:

http://www.popiofamily.com/Colliers_Palomar/index.htm

New exhibit in Milan, Italy:

“Galileo – Images of the Universe from Antiquity to the Telescope”

is already accessible:

http://brunelleschi.imss.fi.it/galileopalazzostrozzi/index_flash.html

The exhibit will be opened on March 13 in Palazzo Strozzi.

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

75 Years Ago Today

75 years ago today, the first 200-inch mirror blank was cast at the Corning Glass Works in Corning, NY. The casting was unsuccessful as the ceramic cores on the underside of the mold broke loose and floated to the surface. I posted about this last year, but today I have some wonderful things to share.

Word got out prior to the casting and a great many spectators came to see the crew handle the molten glass to as they worked to fill the mold. Have a look at the photo and you can see just how close the crowd was to the crew.

Full article and photographs here:

http://palomarskies.blogspot.com/2009/03/75-years-ago-today.html

The July, 2009 issue of National Geographic Magazine has an article by Timothy Ferris on past, current, and future giant telescopes, which is online here:

http://palomarskies.blogspot.com/2009/06/hale-telescope-in-national-geographic.html

Was the telescope invented by a Spaniard?

http://www.ciphermysteries.com/2009/06/21/the-juan-roget-telescope-inventor-theory-revisited

A recent post on the Palomar Skies blog is asking if any of the film and audio

recordings made during the dedication ceremony for the 200-inch Hale

telescope on Mount Palomar are still in existence. At the moment they

seem to be as lost as the original Apollo 11 recordings.

http://palomarskies.blogspot.com/2009/07/lost-history.html

On the telescopes in the paintings of J. Brueghel the Elder

Authors: Pierluigi Selvelli, Paolo Molaro

(Submitted on 21 Jul 2009)

Abstract: We have investigated the nature and the origin of the telescopes depicted in three paintings of J. Bruegel the Elder completed between 1609 and 1618. The “tube” that appears in the painting dated 1608-1612 represents a very early dutch spyglass, tentatively attributable to Sacharias Janssen or Lipperhey, prior to those made by Galileo, while the two instruments made of several draw-tubes which appear in the two paintings of 1617 and 1618 are quite sophisticated and may represent early examples of Keplerian telescopes.

Comments: 5 pages, 3 figures. Proceedings of 400 years of Astronomical telescopes Conference at ESA/ESTEC in Noordwijk. Brandl, Bernhard R.; Stuik, Remko; Katgert-Merkeli, J.K. (Jet) (Eds.)

Subjects: Instrumentation and Methods for Astrophysics (astro-ph.IM)

Cite as: arXiv:0907.3745v1 [astro-ph.IM]

Submission history

From: Molaro Paolo [view email]

[v1] Tue, 21 Jul 2009 15:38:24 GMT (1652kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0907.3745

The mystery of the telescopes in Jan Brueghel the Elder’s paintings

Authors: Paolo Molaro, Pierluigi Selvelli

(Submitted on 19 Aug 2009)

Abstract: Several early spyglasses are depicted in five paintings by Jan Brueghel the Elder completed between 1608 and 1625, as he was court painter of Archduke Albert VII of Habsburg. An optical tube that appears in the Extensive Landscape with View of the Castle of Mariemont, dated 1608-1612, represents the first painting of a telescope whatsoever.

We collected some documents showing that Albert VII obtained spyglasses very early directly from Lipperhey or Sacharias Janssen. Thus the painting likely reproduces one of the first man-made telescopes ever.

Two other instruments appear in two Allegories of Sight made in the years 1617 and 1618. These are sophisticated instruments and the structure suggests that they may be keplerian, but this is about two decades ahead this mounting was in use.

Comments: 4 pages, 2 figures Proceedings 53 SAIt 2009, Pisa

Subjects: Instrumentation and Methods for Astrophysics (astro-ph.IM)

Cite as: arXiv:0908.2696v1 [astro-ph.IM]

Submission history

From: Molaro Paolo [view email]

[v1] Wed, 19 Aug 2009 09:26:07 GMT (3384kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0908.2696

Galileo’s Notebooks May Reveal Secrets Of New Planet

ScienceDaily (Oct. 24, 2009) — Galileo knew he had discovered a new planet in 1613, 234 years before its official discovery date, according to a new theory by a University of Melbourne physicist.

Professor David Jamieson, Head of the School of Physics, is investigating the notebooks of Galileo from 400 years ago and believes that buried in the notations is the evidence that he discovered a new planet that we now know as Neptune.

A hypothesis of how to look for this evidence has been published in the journal Australian Physics and was presented at the first lecture in the 2009 July Lectures in Physics program at the University of Melbourne in the beginning of July.

If correct, the discovery would be the first new planet identified by humanity since deep antiquity.

Full article here:

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/07/090709095427.htm

How Marius Was Right and Galileo Was Wrong Even Though Galileo Was Right and Marius Was Wrong

Authors: Christopher M. Graney

(Submitted on 19 Mar 2009 (v1), last revised 22 Mar 2009 (this version, v2))

Abstract: Astronomers in the early 17th century misunderstood the images of stars that they saw in their telescopes. For this reason, the data a skilled observer of that time acquired via telescopic observation of the heavens appeared to support a geocentric Tychonic (or semi-Tychonic) world system, and not a heliocentric Copernican world system.

Galileo Galilei made steps in the direction of letting observations lead him towards a Tychonic or semi-Tychonic world system. However, he ultimately backed the Copernican system, against the data he had on hand.

By contrast, the German astronomer Simon Marius understood that data acquired by telescopic observation supported a Tychonic world system.

Comments: Or, how telescopic observations in the early 17th century supported the Tychonic geocentric theory and how Simon Marius realized this

Subjects: History of Physics (physics.hist-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0903.3429v2 [physics.hist-ph]

Submission history

From: Christopher Graney [view email]

[v1] Thu, 19 Mar 2009 21:41:23 GMT (87kb)

[v2] Sun, 22 Mar 2009 17:15:19 GMT (86kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0903.3429

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

200″ Mirror Cast 75 Years Ago Today

75 years ago today, December 2, 1934, Corning Glass Works successfully cast the 200-inch mirror for what would become the Hale Telescope on Palomar Mountain.

http://palomarskies.blogspot.com/2009/12/200-mirror-cast-75-years-ago-today.html

http://www.strangehistory.net/2012/06/10/thomas-digges-and-the-telescope/

Thomas Digges and the TelescopeJune 10, 2012

***Dedicated to Larry who sent this one in***

Thomas Digges (1595) is one of those footnotes in history who perhaps deserves a page, a chapter or even a book to himself. An Elizabethan military engineer, Digges also wrote on astronomy and translated Copernicus into English and, fundamentally for the present argument, he pushed the use of experimentation in astronomy, letting the dead letters of Plato and Aristotle just drop away. TD also, and our voice trembles as we say it, may have used the telescope to observe the heavens a generation before Galileo.

What is the proof? Well, in his book on geometrical methods in surveying, Pantometria, published in 1571 he described ‘perspective glasses’.

By these kind of Glasses or rather frames of them, placed in due Angles, yee may not only set out the proportion of an whole region, yea represent before your eye the liuey image of euery Town, Villages &c. and that in as little or great space or places as yes will prescribe, but also augment and dilate any parcel thereof, so that whereas the first appearance an whole Towne shall present it selfe so small and compact together that yee shall not discerne anye difference of streates, yee may by application of Glasses in due proportion cause any peculaire house, or roume thereof dilate and shew it selfe in as ample forme as the whole town first appeared, so that ye shall discerne any trifle, or reade any letter lying there open, especially if the sunne beames may come vnto it, as plainly as if you were corporally present…

Oh the Elizabethans had English to die for… Anyway, there can be no question here – can there? – that Digges is describing some kind of telescope.

An anonymous author who published ‘Thomas Digges: Unsung Hero of Astronomy’ on Astrochix has this to add.

Later in the paragraph [quoted above] Digges mentions a separate volume of the ‘miraculous effect of perspective glasses’, unfortunately this volume has never been found. The existence of ‘perspective glasses’ is also corroborated in a treatise written by William Bourne in 1580. It’s tempting to believe Thomas Digges used these ‘perspective glasses’ to view the heavens, perhaps that’s what even convinced him of the ‘infinite’ nature of stars. Unfortunately there does not seem to be a direct record of him doing so. However, in 1579 Digges printed a list ‘Bookes Begon by the Author, hereafter to be published’, among which was this comment: Commentaries upon the Revolutions of Copernicus, by evidente Demonstrations grounded upon late observations, to ratify and confirme hys Theorikes and Hypothesis….’ The comment ‘late observations’ is interesting and could be taken to mean that Digges did in fact use ‘perspective glasses’ to make astronomical observations.

Incidentally, Thomas Harriot, another English astronomer who corresponded with Digges, traveled to Virginia in 1585, carrying a ‘perspective glass’ – again long before Galileo used one in 1609 to view Jupiter and it’s moons.

It is pretty exciting stuff. Digges undertook his astronomical work from c. 1570-c. 1580: like many irritating polymaths, he dealt with acres of knowledge in a decade and made hay. It is simply inconceivable, given his hands on approach and his interests, that he would not have pointed his perspective glasses at the heavens. The question is what he saw there and whether he made his own deductions based on those findings. Our anonymous author thinks there may be a way to carry this forward.

Francis Johnson made a point in his book Astronomical Thought in Renaissance England, that Digges has a number of letters preserved in the British Museum, which remain unexamined. Mr Johnson believed that careful examination of these records, may provide clues about the development of the telescope.

Anyone based in London with a BM card in their pocket want to dethrone Galileo? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com Immortality awaits you

http://arxiv.org/abs/1206.4244

Learning from Galileo’s errors

Authors: Enrico Bernieri

(Submitted on 19 Jun 2012)

Abstract: Four hundred years after its publication, Galileo’s masterpiece Sidereus Nuncius is still a mine of useful information for historians of science and astronomy. In his short book Galileo reports a large amount of data that, despite its age, has not yet been fully explored.

In this paper Galileo’s first observations of Jupiter’s satellites are quantitatively re-analysed by using modern planetarium software. All the angular records reported in the Sidereus Nuncius are, for the first time, compared with satellites’ elongations carefully reconstructed taking into account software accuracy and the indeterminacy of observation time.

This comparison allows us to derive the experimental errors of Galileo’s measurements and gives us direct insight into the effective angular resolution of Galileo’s observations.

Until now, historians of science have mainly obtained these indirectly and they are often not correctly estimated. Furthermore, a statistical analysis of Galileo’s experimental errors shows an asymmetrical distribution with prevailing positive errors.

This behaviour may help to better understand the method Galileo used to measure angular elongation, since the method described in the Sidereus Nuncius is clearly wrong.

Comments: 8 pages, 5 figures, 2 tables

Subjects: History and Philosophy of Physics (physics.hist-ph)

Journal reference: J. Br. Astron. Assoc . 122, 3, 2012, 169-172

Cite as: arXiv:1206.4244 [physics.hist-ph]

(or arXiv:1206.4244v1 [physics.hist-ph] for this version)

Submission history

From: Enrico Bernieri [view email]

[v1] Tue, 19 Jun 2012 15:47:04 GMT (351kb)

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1206.4244v1

http://arxiv.org/abs/1211.4244

Francesco Ingoli’s essay to Galileo: Tycho Brahe and science in the Inquisition’s condemnation of the Copernican theory

Authors: Christopher M. Graney

(Submitted on 18 Nov 2012)

Abstract: In January of 1616, the month before before the Roman Inquisition would infamously condemn the Copernican theory as being “foolish and absurd in philosophy”, Monsignor Francesco Ingoli addressed Galileo Galilei with an essay entitled “Disputation concerning the location and rest of Earth against the system of Copernicus”.

A rendition of this essay into English, along with the full text of the essay in the original Latin, is provided in this paper.

The essay, upon which the Inquisition condemnation was likely based, lists mathematical, physical, and theological arguments against the Copernican theory.

Ingoli asks Galileo to respond to those mathematical and physical arguments that are “more weighty”, and does not ask him to respond to the theological arguments at all.

The mathematical and physical arguments Ingoli presents are largely the anti-Copernican arguments of the great Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe; one of these (an argument based on measurements of the apparent sizes of stars) was all but unanswerable.

Ingoli’s emphasis on the scientific arguments of Brahe, and his lack of emphasis on theological arguments, raises the question of whether the condemnation of the Copernican theory was, in contrast to how it is usually viewed, essentially scientific in nature, following the ideas of Brahe.

Comments: 61 pages (including two appendices), 5 figures

Subjects: History and Philosophy of Physics (physics.hist-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:1211.4244 [physics.hist-ph]

(or arXiv:1211.4244v1 [physics.hist-ph] for this version)

Submission history

From: Christopher Graney [view email]

[v1] Sun, 18 Nov 2012 18:38:24 GMT (1167kb)

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1211/1211.4244.pdf

“Moon Man”

What Galileo saw.

by

Adam Gopnik

February 11th, 2013

The New Yorker

Although Galileo and Shakespeare were both born in 1564, just coming up on a shared four-hundred-and-fiftieth birthday, Shakespeare never wrote a play about his contemporary. (Wise man that he was, Shakespeare never wrote a play about anyone who was alive to protest.) The founder of modern science had to wait three hundred years, but when he got his play it was a good one: Bertolt Brecht’s “Galileo,” which is the most Shakespearean of modern history plays, the most vivid and densely ambivalent. It was produced with Charles Laughton in 1947, during Brecht’s Hollywood exile, and Brecht’s image of the scientist as a worldly sensualist and ironist is hard to beat, or forget.

Brecht’s Galileo steals the idea for the telescope from the Dutch, flatters the Medici into giving him a sinecure, creates two new sciences from sheer smarts and gumption—and then, threatened by the Church with torture for holding the wrong views on man’s place in the universe, he collapses, recants, and lives on in a twilight of shame.

Full article here:

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2013/02/galileos-genius.html