Growing up in the Sputnik era, I followed the fortunes of space exploration with huge enthusiasm. In those days, the model was primarily planetary in nature, the progression from the Moon to the nearest planets and then beyond seemingly inevitable. At the same time, a second model was developing around the idea of space stations and self-contained worlds built by man, one that would reach high visibility in the works of Gerard O’Neill, but one that ultimately reached back as far as the 1920’s (Oberth and Noordung) and further back to the science fiction of Jules Verne. In fact, E. E. Hale’s “The Brick Moon” explored a space station as early as 1869.

But even as our Mariners and Veneras explored other planets, an interstellar thread was also emerging. Robert Goddard wrote about interstellar journeys in 1918, science fiction was full of such travel as the field matured in the 1940s and ’50s, and serious scientific study of interstellar flight became established by mid-century. Writing in 1979, Michael Michaud could point to Project Daedalus as the first serious starship design, and could note the continuing work of Robert Forward in presenting what he thought of as a roadmap for interstellar expansion.

Reasons for the Journey

It’s useful to frame these issues by seeing how they have been examined in the past, for if we are beginning to adapt to what Michaud calls an ‘extraterrestrial paradigm,’ it is because we have, in reaction to technological breakthroughs and exploration, been forced to adjust our ideas about our place in the cosmos. Michaud’s “The Extraterrestrial Paradigm: Improving the Prospects for Life in the Universe” pulls together his own prior work in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society and the thinking of the scientists and scholars of the day to make the case for a human culture that will expand to the stars out of choices made in the service of a newly emerging sense of purpose.

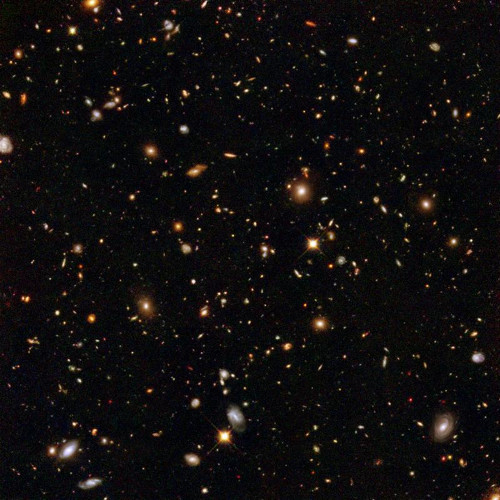

Image: Aswarm with galaxies, this part of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field survey cuts across billions of light-years. Such glimpses of immensity make us ponder the purpose behind human exploration of the cosmos. Credit: NASA, ESA, and R. Thompson (Univ. Arizona).

Solving the riddle of purpose must underlie all our explorations. Why, after all, do we choose to go into space in the first place? Robert Jastrow could find meaning in the linkage between cosmology and the workings of evolution, believing that persistent struggle and striving gave purpose to our existence. Michaud looks toward the loss of energy and structure we call entropy and asks whether life and the intelligence that can grow out of it are the only chance to reverse entropy on a local scale, and in his memorable phrase, “to impose choice on inevitability.”

Michaud’s essay deserves a wider audience, published originally in the academic journal Interdisciplinary Science Reviews and unavailable online. For the choices we make going forward are going to be continuous, given the decades- and probably centuries-long commitment that reaching the stars will require. But the extraterrestrial paradigm begins right here in our own system as we adapt our philosophy and perhaps one day our biology to moving off-planet. And while we have made the case for exploration and scientific research in spaceflight all along, Michaud here explores social and economic issues and the long term survival of the species as key drivers for the development of this new framework.

Expanding the economy beyond Earth’s limits allows us to surmount huge issues of resource depletion on the home world while developing new industrial processes in space. Earth’s energy demands can be met by abundant solar energy at the same time that we expand the human ecosphere to create new habitats beyond the Earth, perhaps modifying existing habitats through terraforming or other means. Moreover, the creation of a multitude of separate biospheres ensures us against collective disaster, whether natural or man-made. In terms of human liberty, freedom is enhanced and diversity encouraged as we experiment with new societies separate from those on Earth. All of these work together in shaping the extraterrestrial paradigm.

Centauri Dreams readers will be familiar with Michaud’s work in these pages, and also with his long-term commitment to developing a strategy for human expansion to the stars. His JBIS work in the late 1970s — three papers collectively known as “Spaceflight, Colonization and Independence: A Synthesis,” drawn on heavily in this essay — extends the colonization and humanization of the Solar System to an outward push to other star systems, one that by its nature changes who we are as we make the choice of who to become.

A New Cosmic Humanism

For humans, Michaud believes, must create their own goals in the absence of a pre-determined purpose imposed on them. The future, on this planet or elsewhere, depends on an evolutionary paradigm that relies on technology as a way to extend human influence into larger environments. It’s a view that suggests an inevitability about the rise of life and intelligence, but this determinism is modulated by chance as well as individual and social choice. That choice offers us the opportunity to bring meaning into the cosmos. As Michaud puts it:

The extraterrestrial paradigm suggests such goals: endless growth, expansion and discovery, the enrichment and rediversification of the species, and the increasing of human knowledge and power in the universe. Extraterrestrial growth could be a grand shared enterprise for humanity. It would define Homo sapiens by contrast with the external environment into which we ventured, and by contrast with nonexpanding forms of life and possibly intelligence on Earth. It suggests a way to free humans of Darwinian competition among themselves.

Above all, Michaud believes that the development of the extraterrestrial outlook helps us create a purposeful place for ourselves in the greater cosmos:

It suggests that, by our own activities, we can ensure the survival of our species, our intelligence, our consciousness, our culture, and that we can make intelligence have an impact on an inanimate, unfeeling universe, giving at least part of it an intelligent purpose. Thus the extraterrestrial paradigm may be an essential part of building a new cosmic context for mankind. It could be the basis for a sort of cosmic humanism that might be a factor in the philosophical history of the future.

Survival of the species demands short-term practical thinking but also the development of shared, long-term purpose, the latter more distant in time and requiring consensus and commitment. It may be that our movement into space expresses that purpose. But there are numerous challenges to the notion, all of which Michaud addresses in his essay. Tomorrow I’ll run through objections to this cosmic context, and go on to discuss how SETI comes into play. What happens to our own sense of purpose if and when we run into another intelligence?

The paper is Michaud, “The Extraterrestrial Paradigm: Improving the Prospects for Life in the Universe,” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews Vol. 4, No. 3 (1979), pp. 177-192. Michaud’s three-part study “Spaceflight, Colonization and Independence: A Synthesis” appeared in JBIS 30, 83-95 (Part I, March 1977); 203-212 (Part II, June 1977); 323-331 (Part III, September 1977).

First things first, NASA needs to accelerate commercial crew right now. Being dependent on the Russians for transport to ISS until 2017 is bad.

Getting back on topic, settlers on Mars and asteroids seems affordable by multiple nations and even by corporations, and would be motivated mostly by a sense of adventure and possibly, profit.

I think interstellar settlement would be driven by cultural reasons, not adventure nor profit. And the cost of interstellar travel would be so high, only one or a very few attempts would be made. Here’s an example of cultural expansion from our past — about 500 years ago, explorers and settlers made the difficult journey from Europe to America. About 450 years after that, despite being enemies at times in between, the USA came to the aid of Great Britain in a world war, and a cultural affinity to the mother country was a powerful reason.

So I can see that interstellar settlement could be supported by a bloc of English speaking countries, mostly justified by cultural (mostly linguistic) expansion and ensuring cultural affinity. After all, the settlers may send envoys bearing gifts someday – and a lot can happen in 500 or 1000 years.

I wish I could believe such a vision is possible.

The key drivers in our world appear to be:

a) power… National security through to cheap political point scoring.

b) greed… Economic self interest

With curiosity and scientific exploration a poor third. Much of the history of the space age since the 1950’s can be seen in this light.

Of course these drivers can be powerful and we may get there in the end, but only if those with the purse strings see some advantage for them in it.

Most of the goals stated in the article could be met within our own solar system, at least for the foreseeable future. Like Randy Chung I think the quest for interstellar flight will be driven by something else.

The early U.S. space program was very much a product of the big-government liberalism that gave us the New Deal, tried to give us the Great Society, and was destroyed in part by the debacle in Vietnam. Our current system seems bent on impoverishing the vast majority of Americans to serve the greed of a few. In a society like that space is the last thing on most peoples’ minds. I am pessimistic that a large-scale space effort will happen again anytime soon.

NS said on March 4, 2014 at 0:55 (in quotes):

“Most of the goals stated in the article could be met within our own solar system, at least for the foreseeable future. Like Randy Chung I think the quest for interstellar flight will be driven by something else.”

If interstellar missions are not conducted by Artilects, there will probably be groups of humans who want to leave the Sol system for political and religious reasons, with the two likely intertwined more often than not. Perhaps even for new “land” assuming much of the viable Sol system is taken. Resources may count into this just so long as you know it will be fairly senseless to bring much of anything all the way back to Earth, which won’t be home any more for these folks anyway, if it ever was by then.

“The early U.S. space program was very much a product of the big-government liberalism that gave us the New Deal, tried to give us the Great Society, and was destroyed in part by the debacle in Vietnam.”

I feel like our last few wars have been huge wastes of time, money, resources, and human beings with little to show for it. Our society better wake up soon that it cannot conduct business as usual when it comes to settling disputes. I am still somewhat amazed that nuclear war did not break out between 1945 and now.

“Our current system seems bent on impoverishing the vast majority of Americans to serve the greed of a few. In a society like that space is the last thing on most peoples’ minds.”

When it becomes viable and overall safe, the very rich will be migrating into space kind of ala Elysium. The Final Frontier will make for some excellent tax shelters, I am sure. I believe something like that was already tried with the old Soviet Mir space station.

“I am pessimistic that a large-scale space effort will happen again anytime soon.”

Let us hope that private industry can reverse our reliance on fickle and short-sighted governments for access to space. We should also pay attention to China and India and even Russia as the next possible dominators of near space. I do not like counting out the USA via NASA, but I really need to see some real commitment from them for a definite plan for the Final Frontier.

You would think with real physical targets out there to aim for, the goals would be relatively easy or at least clear. That is the problem for those of us who grew up during the first decade of the Space Age.

Looking back I wonder what a reasonable next step after the moon landings would have been. Mars was always talked about, but that is so enormously more difficult I can understand why it didn’t happen. People have posted here about proposed asteroid missions, but I don’t recall hearing about them at the time. My friends and I were space buffs with a few family connections to the aerospace industry (one of our dads worked on the Saturn V engines) and if we weren’t aware of clear plans for the future it’s no wonder the general public wasn’t either.

Our main motivators for doing things:

* Economic – once its cheap enough to drill the moon/asteroids, or we get nuclear fusion going and need He3 etc.

* Economic – advertising, the Google moonbase, the Facebook rover,…

* Military/Nationalism – in the next big war, space will be the high ground and perhaps armed space planes and the like will be fast-tracked (if it doesnt kill us all),

* Religious – we find aliens we need to convert,

* Tourism – 50k/100k suborbital flights, hotels in LEO and the moon,

Science comes at the end.

Even exploration is driven by hopes of economic windfall through ownership of resources etc.

The wildcard is human integration with artilects (can’t beat them? become them) – if we get that in 100 years, then we can become the spaceship/rover – then our material needs (and maybe motivations?!) change completely.

Kamal Ali said on March 5, 2014 at 4:03:

“Our main motivators for doing things:

“* Religious – we find aliens we need to convert,”

Unless they have their own deities and missionaries and try to convert us first. Just ask the natives of the New World, the South Seas, and Africa how that worked out for them.

The missionaries may have had the best intentions, but others only saw new land and resources for the taking and took advantage of the situation. Who says ETI might be any different? After all, no one travels across interstellar space just for a lark, I do not care what the species is.

This is the text of my forum on the internet in 1998

IMMORTALITY SYSTEMS

Extra Terrestrial Migration – Gene Engineering

Eternal Life Society

Migrating to Infinite Space-Time.

“We Can Become the Engineers of Our Own Body Chemistry.

– In the Right Environment We Can Live Forever”

Once we get off the finite surface of the planet earth and are capable of living in potentially infinite orbital space, there is no reason to have a finite lifespan.

As engineers of our own body chemistry we can disable the genes that dictate the termination of our lifespan, as scientists have already demonstrated with plants and animals. There is no inherent limit to the “Lebensraum” (living space) in orbital space as there is on our planetary surface.

The life span of each organism is determined by the environment to which it has adapted.

The new environment will be our imagination which we can only fill if we live forever. We have to be immortal. There is no inherent limit to our imagination as long as there is time and space.

The incentive to be a member in good standing in society is the pursuit of immortality. Humankind’s social activity, ultimately its urge to mate, is an instinct, just like the instinct to live. If the purpose of society is to protect and enhance the well being of its members, then providing the means to achieve immortality should be one of its highest priorities. The “New World” must provide individuals with access to the experts, the education and the means to achieve immortality.

The difference between our present world based on the formation and protection of family, tribe, nation and the “New World” is that the latter must have as its goal the pursuit of individual immortality.