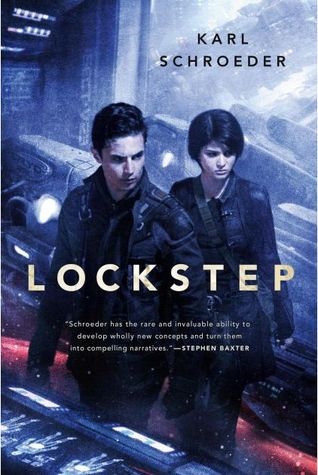

We last heard from Karl Schroeder in his essay Creative Constraints and Starflight, published here back in March. Schroeder was describing his new novel Lockstep, whose ingenious plot is in the service of a daring idea: If we are limited to speeds well less than that of light, can we still find a way to achieve the kind of deep space civilization we’ve seen depicted in so much science fiction? That would include travel to far places within single human lifetimes, trade with colony worlds, and much of the panoply of what is sometimes called ‘space opera.’

Schroeder’s solution is ingenious and challenges the preconceptions most of us bring to interstellar flight, which is why I want to return to Lockstep this morning. I had read a pre-publication copy late in 2013 and found that it triggered some incipient thoughts on how we relate to time that I needed to work out. In particular, not only in Karl’s work but in Neal Stephenson’s and, to an extent, in Alastair Reynolds’, I’ve found a creative re-casting of our relationship to time and how we measure it off in terms of a single human lifetime. Exactly what is ‘subjective’ time, and is there a specific way it should relate to ‘objective’ time?

The question Schroeder forces upon us is whether time is best measured as a clock-driven passage of minutes, hours and days (I call it ‘objective’ time while acknowledging its malleability in the form of spacetime), or as an accumulation of life experiences that can be separated from this objective time. In the world of our experience, we may think of time as a substrate through which we move — we have so many years in our lives and the clock is always ticking in the background. In the world of Lockstep, that ticking can be suspended. Adjusted. The human experience of time is what it has always been, but the world around it is accelerated.

Benefits of Adjusted Chronology

We’re in a world where suspended animation is routine and about as eventful as getting into bed for a good night’s sleep. You might sleep a day, or a year, or in the case of young Toby McGonigal, the book’s protagonist, a breathtaking 14,000 years before waking up. While conventional, day to day life goes on elsewhere, the Lockstep worlds are those that have entered into a contractual arrangement to use suspended animation to stay synchronized. A 360/1 schedule, the primary one in this culture, keeps people suspended for 359 months out of every 360. It’s this last month in which they awake and get about the business of civilization.

Karl has already described this scenario in our pages and we’ve had discussions about its pluses and minuses. But let’s look back and review for a moment what a society like this gets from this strange arrangement. You can see that the so-called ‘fast worlds’ — the inner planets, for example, living as we do today without recourse to suspension — suffer from constraints that the tiny outer worlds in the far Kuiper Belt and beyond don’t endure. As Toby gets used to the world he has awakened into, he marvels at its fecundity. “We’re in the middle of nowhere between the stars but this place seems as rich as Earth. Though that can’t be.”

But of course it is, for reasons he comes to learn, just as he learns the key role his own family has played in this outcome. Schroeder describes all this in terms of computer technology. The locksteps, small worlds synchronized on their schedules with each other, form a synchronous network, with each node acting at the same time. In other words, imagine a large number of tiny, isolated worlds in the Oort Cloud, all sending out their cargo (including passenger ships) on the same schedule. Tuning the ‘frequency’ properly can turn desolate outposts into economically viable societies, for reasons Schroeder is careful to explain in a book where the consequences of this tuning are extremely well thought out and depicted with real panache.

There were tiny colonies that didn’t own even a chunk of cometary ice but harvested the impossibly thin traces of gas found between the stars using modified magnetic ramscoops. In an abyss so empty that there was only one hydrogen atom per cubic centimeter, the scoops filled their vast lungs like baleen whales filtering tenuous oceanic plankton. It could take them decades to fuel a single fusion-powered ship with enough hydrogen to visit their nearest neighbor. Yet even these little starevelings could contribute to the wealth of Lockstep 360/1, because its clock ticks were slow enough for them to keep up.

Automate your industry and go to sleep. When sufficient time has passed to allow the accumulation of a viable amount of resources, you emerge to engage in the necessary trade with other worlds like your own, worlds on the same schedule. A richer world might join a faster lockstep since it could manufacture goods at a greater clip, but even the poorest world has the chance to be part of a functioning civilization at a slow speed. Travel between the worlds takes a lot of time — remember, we’re in a world where Einstein’s speed limit still applies — but on a 360/1 schedule, you might travel half a light year while ‘wintering over,’ as Schroeder calls it.

That makes long periods of suspended animation a genuine plus for those with a yen to engage with the greatest number of the more distant worlds. A wintering over journey at a 36/1 schedule can have a certain number of destinations within range, but a 360/1 lockstep can deal with a thousand times more worlds. Doubling the distance you can travel opens up more distant worlds scattered through three-dimensional space, and a kind of empire can emerge that has resonances with everything from Doc Smith’s clanky space tales to the world of Star Trek.

Differentiation of the Culture

But back to the human experience of time, which is what fascinates me about what Schroeder is doing here. The understandable immediate reaction to a lockstep is that it simply slows the pace of discovery — how to progress when people only wake up briefly every thirty years? But the question is, progress on whose terms? For those whose lives take place within the lockstep, the framework of time outside has been abandoned. They still can expect to live their allotted lifetime, but it’s a lifetime that might take in vast stretches of time during which, to civilizations not in a lockstep, their own empires might rise and fall as the lockstep goes about its way.

All he could really sort out was that humanity and its many subspecies, creations and offspring had experienced many rises and falls over the aeons. Since they had the technology, and lots of motivations, people kept reengineering their own bodies and minds. They gave rise to godlike AIs, and these grew bored and left the galaxy, or died, or turned into uncommunicative lumps, or ran berserk in any of a hundred different ways. On many worlds humans wiped themselves out, or were wiped out by their creations. It happened with tedious regularity. The only reason there were humans at all, these days, was that there were locksteps.

I think this is fascinating — the lockstep as a backup, a repository for the entire species. Schroeder continues:

They served as literal freezers, preserving ancient human DNA and cultures. All kinds of madness might descend upon the full-speed worlds circling the galaxy’s stars — expansions, contractions, raptures, uploading, downloading, mind control, and body-swapping plagues (quite apart from the usual wars, dark ages and terraforming failures) — but everybody ignored those useless frozen micro-worlds drifting between the stars. Their infinitesimal resources and ancient cultures held no interest to the would-be gods of the inner systems. So once those would-be gods had wiped themselves out, the telltale silence from formerly buzzing stars would alert this or that lockstep, and they would send some colonists back. A few millennia later, the human population on Earth and the other lit worlds would again number in the billions or trillions, and some of those would return to the locksteps…

It’s a way of living deep into the remote future, this lockstep, and it sets up levels of civilization that work at different rates of time, from those who continue, as we do, to live one day for every day that passes, to those who adjust that schedule according to the needs of their environment, which out in the Kuiper Belt or Oort Cloud can be quite different. Freeman Dyson has often talked about the biological differentiation that will occur in our species as we adjust to varying conditions moving outward from the Sun. Schroeder is describing a chronological evolution that takes place as entire cultures become disconnected by their choice of calendars.

So how do you feel about it? Is sleeping for thirty years a waste of time? Or is a lockstep a way to continue to live your entire life while what gets ‘burned’ is time that is of little value to you? I’ve always found Karl Schroeder’s work provocative, but Lockstep is a book that keeps coming back to me at odd moments, as I wonder whether people would voluntarily enter into these arrangements in a world where suspended animation was easy, and whether the benefits of a lockstep to the teeming worlds on the Solar System’s edge would outweigh the break from the culture that had spawned the original colonists. I don’t have the answers here, but good science fiction, and this is very good science fiction, asks extraordinarily provocative questions.

Very interesting post! Definitely keen to read this book now. I wonder how you can enforce a lockstep in any sensible way though? Won’t it always be to the advantage of any single community to drop out even if only by a little bit, so they can catch up with the competition?

‘wintering over,’ as Schroeder calls it.

KARL and PAUL: I don’t think I could live without the animal kingdom surrounding me…Do I get to keep my dogs with me too? A trivial point to some but a deal breaker for me…I’m one who assumes nothing…Do I have to get used to having a different pet every time life resumes…A strain on the emotions…This is a gut wrenching movie or television series…

The way to neutralize time as an obstacle to multigenerational startravelling , is not necesarily by inventing a new kind of Warp-Factor called ”adjusted cronology” . As far as we know , the existing kind of humans cannot be frozen. The human brain is the last step on the evolutionary ladder , and as such will probably be the most difficult to freeze without major damage .

Until we have reason to believe otherwise , it would be more pragmatic to look at natures own existing way of ”slowing down time” . Many species have prooved capable of existing completely unchanged for milions of years in limited environments and small populations . A single Eucalytus tree in Australia has spred itself through the roots for 5000 kms , during a period of 15000 years ,without changing a single gene on the way .

Our own species in the past has prooven perfectly capable of surviving on small isolated ilands for thousands of years . This prooven capability can be enhanced by the use of a few million frozen embryoes , and a better understanding of the general function of human beings in limited environments .

Another question is , if humans can be made radiation resistant , by incorporating genetic maschinery capable DNA repair on a bigger scale than our own . This might be much easyer than making us freeze-resistant .

There is another way around this time issue, could the space travellers not just be born, live and die and then be reborn again, same genes, your sort of out of synch twin so to speak. If I knew I that I would be reborn, ok no memories suffice what I wanted to be recorded of my previous lives I would have no problem with knowing that I was going to die. If you are really bad in one life you are not reborn though.

Now to this subjective-objective time conundrum, I was in a lot of pain once and was given medication for it, to me time slowed down, there seemed to be more hours in the day!

Classic psychological theory of memory is that you best remember that which you pay attention too. Anyone who has ever had the misfortune to experience PTSD will know that all too well, but for the rest of us the best way to have our attention grabbed is novelty. In general the more experience one has , the less novelty one is confronted with . Ageing would do this and ironically there is evidence of this contributing to the subjective experience of time . You live your life from one novel experience to another . Of course as things become less familiar and less novel , the quicker life seems to pass. All of us from middle age onwards probably are familiar with this. So time is a subjective thing , “relative” as Einstein famously stated. This book evokes the whole experience of the passage of time . Presumably even in a life lived in “snap shots” over centuries , that one month would end up passing very quickly unless you aggressively looked up new experiences during each waking. It might even be like a drug, with increased risk taking to get that extra “fix” of originality. That’s the theory anyway…..

What would happen if this world meets a FTL propulsion using aliens? Surely it would devastate the humans, or they would acquire the tech, and the lockstep would be a history.

I do hope that the author has secured any potential gaming rights. Would make an interesting story for an awesome game.

There is a way to force large populations to do things in lockstep, but we have seen those kinds of governments and social orders before and they tend to treat human beings as machine parts. The result is usually a lot of dead and damaged “machine parts” and either an eventual collapse of the system or one that functions but just barely.

Humans are amazingly individualistic, even in the societies that do their darndest to keep everyone in line with the groupthink. It can be a pain but it has also spurred innovation and kept human society from becoming a complete collection of totalitarian regimes.

That being said, humans are also still very tribal in nature. One study shows they do not function very well in a democratic sense above 100 in number. Our shiny toys distract us from the fact that we are not so far from the caves and savannas as we like to think we are.

This is why I think humans will need to be radically altered to survive and thrive in space. Not just to adapt to different environments but also to handle the dangers of space and alien worlds psychologically. Which will mean we won’t be quite the humans we are now any more. But that is because we have not naturally evolved to handle such a situation; nature will need a helping hand if we really want to live out there, assuming we do not terraform new places to live or want to put our brains in robot bodies.

What this also means is that those who are planning long and permanent space journeys and settlements really need to think of the human factors or risk major failure. The days of the macho astronauts zipping around Earth in a tin can for a matter of days to months should start being put behind us – five decades after the first humans were put into orbit.

Interesting story. It’s important however to keep the distinction between physical time and time that would be rendered to the individual through suspended animation. Suspended animation could be thought of in a sense of time travel for simply the reason that cellular processes as I understand it are rendered almost to the point of no molecular activity.

However you have to bear in mind that this type of suspended activity’s STILL does have the thermodynamic properties that there is SOME activity going on in a person’s body. This means that if your voyages thousands upon thousands of years that there will be some decay going on within the human person. On the other hand time dilation related to Einstein’s theory states that the time nearly becomes suspended as the vehicle approaches lightspeed. To me this would mean that thermodynamic decay would not occur with regards to the time dilation process. Thus voyages requiring many thousands upon thousands years would still retain persons youthfulness as compared to the suspended animation.

James D. Stilwell writes:

Why not take them with you? In the novel, there’s no reason for an animal not to winter over as well.

The rather sad news about Shumacher and this story has me thinking about how long we can induce artificial comas “safely”. If for instance we can do it for 3-6 month periods, journeys to Mars become a bit more feasible, at least in terms of resources, boredom issues as well as living space. I reckon we’d still need a “watch” person but this could possible be done remotely from Earth and robotically/computerised in situ.

Another way to organise a ‘lockstep’ culture within an Oort Cloud would be to freeze everybody most of the time, and only wake them up whenever a visiting spaceship arrives. With Oort cloud objects (on average) tens of AU apart, these visits will be rare.

When a new ship arrives the colony can wake up and interact with the visitors in real time, and also read any stored messages sent by the other objects; but even if two or more colonies wake up at the same time, they will still be separated by light hours of time and distance (at the very least).

Whether our descendants were to get there by sleeper ships, frozen embryos/gametes, or some other method… it seems that if you have enough people around you to create a viable society with a common culture, you won’t care as much if you were separated by 500 years of cultural/technological development back on earth … unless, maybe just as you reach your destination you receive a radio message that light-speed capable battle ships will be arriving from earth next week to pick up conscripts…

When reading the novel the first thing that came to my mind was, why hibernating for a specific period of time? Why not slow down our aging mechanism and perception of time to a rate similar to the 30 year hibernation period. This would assume we could extend the human body life span into the 28000 year range but then again, hibernation technology is science fiction as well.

Larry, individualism doesn’t always mean going against mass movements – if you don’t like the Lockstep it’s easy to emigrate, for example. But the advantages surely out weigh the tedium of wait times. But read Karl’s tale for a better idea of how it’d work.

OTOH there’s always the possibility that some clever person will figure out how to send sunshine to the worlds between the stars. Power-beaming or even teleportation may allow the fast worlders to claim the dark planets. There’s a lot of potential real estate out there. And stars like the Sun make billions of times more energy than Earth receives so there’s plenty to spare.

I find the idea extraordinarily silly. Chiefly because “normal time” folks have a technological development rate 360 times faster than the locksteppers, and will soon regard the locksteppers as hopelessly primitive. Also because people can and will cheat, to whatever advantage that amounts.

Charles Sheffield had a similar system in his novel Between The Strokes Of Night (1985)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Between_the_Strokes_of_Night

Scientist invent a sort of suspended animation where you are still conscious but you perceive time at 1/2000th the normal rate. This is called “S-Space”.

So if your starship travels at 0.1c, it takes 40 years of normal time. But to a person in S-Space consciousness, it only seems like 7 days.

Of course for an S-Space person to feel like the ship is under 1 g of acceleration, the ship actually only accelerates at 1/2000th g

Tesh,

Alternatively, you could engineer an animal to wake you… it would have to be one capable of sleeping as well, with a very accurate clock to wake itself in time for-

One question, unanswered in the story, is why anyone would opt for the 360/1 Lockstep when very long lifespans are possible – given 14,400 years of fast world history, longevity treatments should be standard.

Instead of just lock stepping in on-off modes, it is enough to just alter the metabolic/psychological passage of time. This would have several interesting consequences:

The perception of time is accelerated, so if say, a year in real-life passes in a day on your psychological time, things like perceived luminosity of sky objects gets amplified by a proportional amount, just because there is a larger amount of photons inciding in your retina per unit of PsyTime (psychological time).

In remote Oort cloud objects, being at a slower pace with a slower metabolism, means that less power is required to operate in real time. But also, the perceived luminosity from the Sun is amplified by 365 (in the case mentioned above where a year is converted into one day of PsyTime). Also, the luminosity of the whole Milky way gets a similar boost for the same reason.

“Of course for an S-Space person to feel like the ship is under 1 g of acceleration, the ship actually only accelerates at 1/2000th g”

Only with regards to the speed at which objects appear to “fall down” inside the ship, but the force felt would still be the same.

In Greg Egan’s “Schild’s Ladder” the protagonist’s home planet goes into slow-motion while one of their envoys is visiting another star-system. Non-sentient robots keep things running as they should in normal time, while the people experience the time in synchrony with the envoy (roughly, since their mind is beamed between stars and their body is in a state of suspension while they’re off elsewhere.) The protagonist and a friend speed up to normal time briefly in a (slightly) naughty act of adolescent defiance.