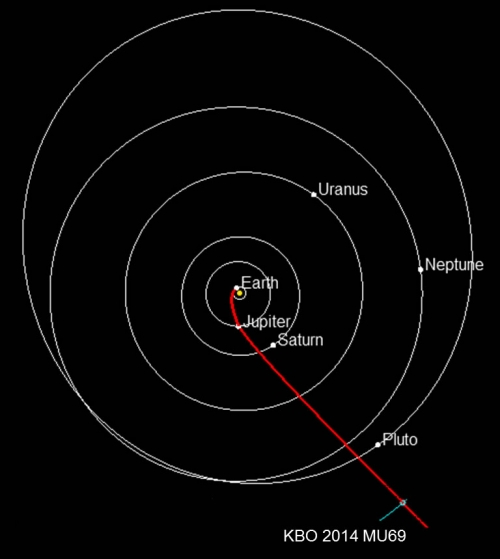

Another surprise from New Horizons, in a year which will surely see a few more before it ends. After all, we have a long flow of data ahead as the spacecraft continues to return the information it gathered during the July flyby of Pluto/Charon. Now we focus on Charon and the crater being called Organa, which produced an anomaly when scientists studied the highest resolution infrared compositional scan of the moon available. This crater and some of the surrounding materials show infrared absorption at about 2.2 microns, indicating frozen ammonia.

Not far away on Charon’s Pluto-facing hemisphere is Skywalker crater, which under infrared scrutiny shows the same composition as the rest of Charon’s surface. Here water ice — not ammonia — dominates. As this JHU/APL news release notes, ammonia absorption was first detected on Charon as far back as 2000, but what we’re seeing here is unusually concentrated. In any case, why is Organa so different from Skywalker and the rest of Charon’s craters?

Image: This composite image is based on observations from the New Horizons Ralph/LEISA instrument made at 10:25 UT (6:25 a.m. EDT) on July 14, 2015, when New Horizons was 81,000 kilometers from Charon. The spatial resolution is 5 kilometers per pixel. The LEISA data were downlinked Oct. 1-4, 2015, and processed into a map of Charon’s 2.2 micron ammonia-ice absorption band. Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) panchromatic images used as the background in this composite were taken about 8:33 UT (4:33 a.m. EDT) July 14 at a resolution of 0.9 kilometers per pixel and downlinked Oct. 5-6. The ammonia absorption map from LEISA is shown in green on the LORRI image. The region covered by the yellow box is 280 kilometers across. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

Organa and Skywalker are roughly the same size, about 5 kilometers in diameter, and both show the same ‘rays’ of ejected material, although Organa’s central areas are darker. But there seems to be no correlation: The ammonia-rich material extends beyond the dark area. One possibility is that the impactor that created Organa was rich in ammonia. An alternative posited by Will Grundy (New Horizons Composition team lead, Lowell Observatory) is that the crater could have been the result of an impact into a pocket of ammonia-rich subsurface ice.

“This is a fantastic discovery,” says Bill McKinnon (Washington University, St. Louis), deputy lead for the mission’s Geology, Geophysics and Imaging team. “Concentrated ammonia is a powerful antifreeze on icy worlds, and if the ammonia really is from Charon’s interior, it could help explain the formation of Charon’s surface by cryovolcanism, via the eruption of cold, ammonia-water magmas.”

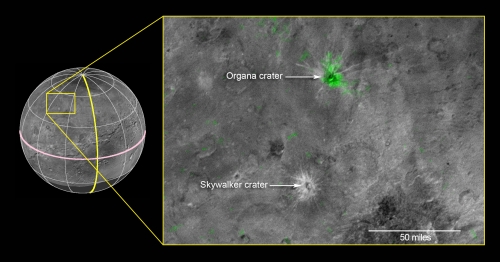

Meanwhile, New Horizons has now completed the third of its four trajectory-adjusting maneuvers needed for intercept of Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69. This was a 30-minute burn with the craft’s hydrazine thrusters and all indications are that it was successful. The fourth and final targeting maneuver is scheduled for today (November 4), although adjustments will be made later in the mission as more information about the KBO’s orbit is obtained. Remember that we only found 2014 MU69 in 2014, after a long search for a Kuiper Belt candidate.

Image: Projected route of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft toward 2014 MU69, which orbits in the Kuiper Belt about 1.6 billion kilometers beyond Pluto. Planets are shown in their positions on Jan. 1, 2019, when New Horizons is projected to reach the small Kuiper Belt object. NASA must approve an extended mission for New Horizons to study the ancient KBO. Credit: JHU/APL.

Is there any (remote) chance to get another KBO flyby beyond 2014 MU69?

May JWST launch on (much revised) schedule and NH can get enough JWST time.

Cool, I suppose the mechanism is similar to formation of KREEP material in moon, ammonia expelled from freezing water ice, until only very ammonia rich liquid is left to freeze, thus concentrating it to certain places.

‘One possibility is that the impactor that created Organa was rich in ammonia.’

This unlikely as the impact energy is sufficient to have completely vaporise the ammonia rather than leave it in place. It is more likely that ammonia rich material lies below the surface and upwelled from the impact.

Mister Gilster , who is in charge of the New Horizons missions from the standpoint determining the trajectory and what bodies will be visited, now that they’ve gone beyond Pluto ? I know they have a scientific team that I think is John Hopkins applied physics Lab, but I wonder whether or not it is JPL who handles all the rest of the targeting and whatnot.

I started to read astronomy books when I was in my early teens, it was in the middle of the 90s. Ever since that time I’ve hoped that we could one day reach Pluto and Charon, which seemed like such mysterious planets on the outskirts of the solar system. It took two decades of waiting and it seems that it was well worth it. The amount of surprises and planetary twists that the double system has thrown at us exceeds all expectations.

What an exciting time to be an astronomy fan. I feel like a I’m 15 again, I’m experiencing the same level on excitement when I first read about the Vikings on Mars and the Voyager near Jupiter.

Charlie writes:

As far as I know, these targeting decisions and trajectory adjustments are handled through the Applied Physics Lab (JHU/APL), but exactly who else they draw on probably depends on the situation. You might want to poke around the New Horizons site or even direct the question there on the specifics of the latest trajectory burn.

How NASA is getting New Horizons to its next celestial target:

http://www.wired.com/2015/11/how-nasa-is-steering-new-horizons-toward-a-tiny-space-rock-in-the-kuiper-belt

NASA Blames “Organizational Confusion” for Embargo on Latest New Horizons Results:

http://spacenews.com/new-horizons-reveals-new-mysteries-about-pluto/

However Pluto’s cryovolcanoes and floating mountains could not care less what humans think or do, just like the rest of the Cosmos:

http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20151109

If this is what we are finding on our very first expedition to a Kuiper Belt Object, and a flyby no less, just imagine what secrets the billions of other such bodies may hold.