The other day I made a crack about a particular piece of artwork not being up to snuff, said item being an illustration accompanying a news release about a recent astronomical find. Maybe I was just out of sorts that day. In any case, what’s significant to me about much of the artwork floating around to illustrate news stories is that it’s generally quite good. Sure, we’re talking about ‘artist’s concepts’ of things like exoplanets and other distant objects, but they’re usually concepts informed by current data and they’re well executed.

Then I ran across Jeff Foust’s essay on art and space in the Space Review and got to thinking about what had propelled me as a kid into this kind of work. We had a fabulous network of community libraries in St. Louis back in the 1950s and ’60s, and I made good use of three of them in particular. I’d stock up on science books and more or less read the astronomy sections straight through, starting at one end and working across. The photographs of astronomical objects were helpful, but the artwork was often what seized my mind.

Image: An artist’s conception of the Milky Way as seen from outside. Credit: NASA, ESA and The Hubble Heritage Team (AURA/STScI).

Naturally, Chesley Bonestell comes to mind, the man responsible for blowing more minds in that era than any other space artist (I still see Titan in Bonestell’s terms, despite everything we’ve learned about it since). Be sure to read Gregory Benford’s reprint of an early essay he wrote on a visit to Bonestell’s home. A snippet:

Does he ever read the things he has illustrated? No, he doesn’t like science fiction very much. Not enough solidity, perhaps. He rarely if ever willingly puts a human artifact into his work, a spaceship or a pressure dome, or a space-suited figure. He doesn’t have any idea of what the future will bring and feels awkward trying to visualize it. But stars and planets, yes, the astronomer friends he has can give him descriptions of how things must be there and he can see it, too, in some closed mind’s eye, so that it comes out right. Most science fiction is quickly outdated, anyway. Look at all the fins on space ships, and the cloudless Earths. Better to stay away from it.

Fascinating. But Foust reminds me that so doughty a figure as Alan Bean is a well-known artist in his own right, having recently opened an exhibition at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington. It’s amusing to see him quoted as saying people used to chide him about painting Earthly scenes. After all, he was the first artist in history to go some place besides the Earth. Why wasn’t he painting scenes from his Apollo 12 experience in 1969?

Bean went on to become a full-time artist, and I can only imagine the reaction of some of his associates when he made that move. Now he’s working in intriguing mixed media, using textures he creates from objects like lunar spacesuit boots and working lunar dust particles into his work, extracted from the patches of his suit. If the first career was satisfying, Bean now says he has developed “the heart of an artist,” a changeover that took 28 years to accomplish.

Image: Alan Bean surrounded by his paintings. Credit: Alan Bean.

Foust also looks at a panel on space art at the recent Mars Society Convention at the University of Maryland, where author Andrew Chaikin reminisced:

“I can say that I’m probably sitting here today because of space art. That’s what hooked me when I was five years old. The illustrations in my astronomy books when I was a kid were, as I have written, like ‘magic portals’ that transported me from my parents’ house to other worlds.”

Chaikin and I seem to have shared a common childhood experience. And I also think Emil de Cou, associate conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, is on to something important:

“There used to be a much closer overlap between the imaginative source of science and art that was shared in the years before that caught so much of our imagination. That’s why everybody is in this room today, not so much because of some hard scientific fact that you read as a child, but it was from reading Amazing Stories magazine, or watching Star Trek or Lost in Space.”

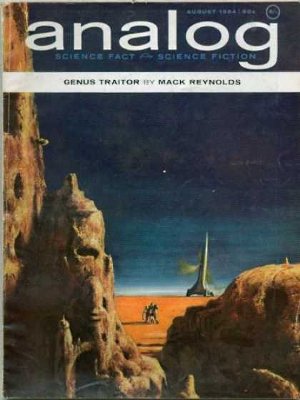

In my case, it was indeed Amazing Stories, along with the Astounding/Analog of the later Campbell era and H.L. Gold’s Galaxy, that provided much of the imagery. Those wonderful magazine covers worked their magic as much, if not more so, than blurry views from Palomar, keeping me wondering what it would be like to actually see some of these objects up close, if not walk upon their surfaces. Can art reawaken the spirit of exploration that seems so much on the wane?

Let’s hope so. We have no shortage of talented artists working this turf, and the Net is spreading their work more widely than ever. Have a look at the members’ page for the International Association of Astronomical Artists, where you’ll find Web sites listed for Lynette Cook, Don Dixon, Dan Durda, David Hardy, Rich Sternbach and many more. A few hours exploring these scenes may remind you of that early thrill of discovery that propelled so many into space sciences.

When I was living in Italy many years ago, the only regular science fiction publication was Urania. It mostly published translations American stories 10 years older (I guess for cost reasons).

Most of the covers were from Karel Thole and some were quite fascinating, even when the story was actually a disappointment. They must have had the same effect on other people too as someone has gone to the trouble of scanning them all and putting them online. Someone even wrote a science fiction story on Urania’s covers.

There’s a short biography of Karel Thole on Wikipedia :

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karel_Thole

Searching for pictures on Google returns a lot of his work.

The complete list of Urania’s covers can be found here :

http://www.mondourania.com/urania/uraniaelencopagine.htm

Some of the strangest :

http://www.mondourania.com/urania/u681-700/urania693.htm

http://www.mondourania.com/urania/u1021-1040/urania1032.htm

http://www.mondourania.com/urania/u621-640/urania622.htm

It’s a hard thing to really get a space scene across, that mix of the familiar (snow on Titan, blue sky, sheer cliff faces) and the alien (Saturn, rings, deep purple zenith), making the image a compelling attractor for the imagination. First time I saw Bonestell’s Titan, in an old Time-Life book, I was instantly captivated. Not long afterwards all those old ‘Titans’ were made fiction by the ‘Voyager’ flyby of the real Titan. Bonestell’s blue sky and snowy cliffs became high orange haze and a teasing mystery for the next ~+20 years until ‘Huygens’ fell out of the sky and snapped those photos. The real Titan is even more puzzling, more teasing and alluring than Bonestell’s, but his painting will always be ‘Titan’ to me.

There is also Novaspace, where many of these talents and more congregate. And one of the loveliest books in this category is Bill Hartmann’s Cycles of Fire. Beautiful space art is truly ambrosia for the spirit!

I love what art can do whit the imagination, I often find some fantastic stuff at art communities like DeviantART. Try to look at some of the young ppl sci-fi stuff. It is absolutely incredible how much talent there is out there.

This Web site has many covers from science fiction magazines of yore:

http://www.sfcovers.net/

Richard M Powers,lets us not forget, and those whom do not know of his oeurve:

http://home.earthlink.net/~cjk5/

good stuff…

Mark

I’m so glad you mentioned Powers, Mark. His work casts a spell over me that is unbroken over the decades.

indeed. space art is important in depicting possible futures, and allowing someone to grasp abstract concepts like living in a dome on a far off planet. it presents the ideas of science fiction and science in a compelling way, and brings possible futures to life.

im personally intrigued by scifi illustrations, as well as concept art of distant exoplanets and black holes.

art and literature based on space helps shift our mindset towards the idea that “the whole world” is only one world, and that space is not just a distant view but a frontier for civilization.

An excellent piece on space art (and thanks for the mention!). But I was very surprised to read this excerpt from a piece by Greg Benford, on Bonestell:

“He rarely if ever willingly puts a human artifact into his work, a spaceship or a pressure dome, or a space-suited figure. He doesn’t have any idea of what the future will bring and feels awkward trying to visualize it.”

I find this hard to believe, considering the number of spaceships, spacemen, domes, etc. that Bonestell DID paint — and so brilliantly! (In the case of those, of course, rather than astronomers he would consult with scientists and engineers like Wernher von Braun or Willy Ley.)

September 15, 2009

Astro Art: Artist Creates Portrait Gallery of Astronomers

Written by Nancy Atkinson

Art and astronomy often intersect, and it’s wonderful when art can provide an emotional connection to science. Amateur astronomer and artist Sayward Duffano has captured the personalities of several astronomers through history as well as individuals in astronomy related fields in a gallery of paintings she created especially for the International Year of Astronomy.

“I knew I wanted to paint something special for the IYA,” she said. “So last year I had started painting a few astronomers, some planets, and some other types of astro art.”

And Sayward says she is looking for a place to display her work.

“Originally, I was working on a print and book project, but due to the recent downturn in the economy, those plans were not able to be realized,” she said. “I’m not trying to sell the originals, but I do want them to be able to be seen because of their subject matter and they were painted especially for the IYA.”

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/2009/09/15/astro-art-artist-creates-portrait-gallery-of-astronomers/

Spreading space art to a wider audience had a lot to do with my agreeing to chair the National Space Society’s first space calendar project where I pushed for going with a space art contest as opposed to either just grabbing non-copyrighted NASA images or licensing existing art. The art generated by that contest can be seen at http://www.nss.org/settlement/calendar/2008/gallery.htm

With respect to the art of Alan Bean, there is an interview I did with him many years ago on my web site at: http://www.artsnova.com/space-artist-alan-bean.html

Finally, Andy’s comments about the influence of space art on him during his childhood ring true for me as well.

Jim, the NSS contest generated some memorable images (I love ‘The Return to Abalakin’). Thanks for the link, and the link to your interview with Alan Bean as well.

Great post. I, too, was surprised by Gregory Benford’s statement on Chesley Bonestell rarely, if ever, willingly putting human artifacts in paintings. I remember a lot of them and one specifically that has a suited astronaut discovering Chesley’s sig carved into a foreground rock. Perhaps this was at the suggestion of an art director. The paintings That usually are devoid of humans are the California Mission series. A wonderful collection of work. He really liked painting architecture.

Our studio is in Carmel not far from Chesley’s former home. I had long planned a visit to see him while I was living in Rochester, NY and then a little closer in Laguna Beach, CA. During that period, I was here a few times working for Penske Racing. Couldn’t take personal time to go see him, though. A few years later, I found myself moving to Carmel and the pilgrimage would surely happen. Was called back to Rochester for three months and I learned of his passing while I was there. I will always regret not making that visit a priority, no matter where I happened to be living. His work started my path to being a space artist and I often wonder what we would have spoken about during my visit and if he would have liked my work and perhaps given some pointers.

Paul Bock: the art of science

Whether biochemist Paul Bock is painting a picture or conducting research on blood coagulation, creativity is the name of the game.

Full story:

http://www.vanderbilt.edu/exploration/stories/bock.html

http://www.universetoday.com/95395/visions-of-the-cosmos-the-enduring-space-art-of-david-a-hardy/

Visions of the Cosmos: The Enduring Space Art of David A. Hardy

by Nancy Atkinson on May 30, 2012

‘Moon Landing:” This is one of Hardy’s very earliest paintings, done in 1952 when he was just 15. It was also the first to be published. Credit: David A. Hardy. Used by permission. Click image for access to a larger version and more information on Hardy’s website.

For over 50 years, award-winning space and astronomy artist David A. Hardy has taken us to places we could only dream of visiting. His career started before the first planetary probes blasted off from Earth to travel to destinations in our solar system and before space telescopes viewed distant places in our Universe. It is striking to view his early work and to see how accurately he depicted distant vistas and landscapes, and surely, his paintings of orbiting space stations and bases on the Moon and Mars have inspired generations of hopeful space travelers.

Hardy published his first work in 1952 when he was just 15. He has since illustrated and produced covers for dozens of science and science fiction books and magazines. He has written and illustrated his own books and has worked with astronomy and space legends like Patrick Moore, Arthur C. Clarke Carl Sagan, Wernher von Braun, and Isaac Asimov. His work has been exhibited around the world, including at the National Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C. which houses two of his paintings.

Universe Today is proud to announce that Hardy has help us update the banner at the top of our website (originally designed by Christopher Sisk) to make it more astronomically accurate.

Hardy has also recently debuted his own new website where visitors can peruse and learn more about his work, and buy prints and other items.

We had the chance to talk with Hardy about his enduring space art and career:

‘Skiing on Europa’ by David A. Hardy, 1981. Used by permission.

Universe Today: When you first started your space art, there weren’t images from Voyager, Cassini, Hubble, etc. to give you ideas for planetary surfaces and colored space views. What was your inspiration?

David Hardy: I got to look through a telescope when I was about 16. You only have to see the long shadows creeping across a lunar crater to know that this is a world. But I also found the book ‘The Conquest of Space‘ in my local library, and Chesley Bonestell’s photographic paintings of the Moon and planets just blew me away! I knew that I wanted to produce pictures that would show people what it’s really like out there — not just as rather blurry discs of light through a telescope.

UT: And now that we have such spacecraft sending back amazing images, how has that changed your art, or how have the space images inspired you?

Hardy: I was lucky to start when I did, because in 1957 we had Sputnik, and then the exploration of space really started. We started getting photos of the Earth from space, and of the Moon from probes and orbiters, then of Mars, and eventually from the outer planets. Each of these made it possible to produce better and more realistic and accurate paintings of these worlds.

‘Ferry Rocket and Space Station’ by David A. Hardy. Used by permission. Hardy’s description: ‘A wheel-shaped space station as designed by Wernher von Braun, and a dumbbell-shaped deep-space vehicle designed by Arthur C. Clarke to travel out to Mars and beyond. The only photographs of the Earth from space at this time were a few black-and-white ones from captured German V-2s.’

UT: We are amazed at your early work — you were so young and doing such amazing space art! How does it feel to have inspired several generations of people? — Surely your art has driven many to say, “I want to go there!”

Hardy: I certainly hope so — that was the idea! In 1954 I met the astronomer Patrick Moore, who asked me to illustrate a new book in 1954, and we have continued to work together until the present day. Back then we wanted to so a sort of British version of The Conquest of Space, which we called ‘The Challenge of the Stars.’ In the 1950s we couldn’t find a publisher — they all said it was ‘too speculative!’ But a book with that title was published in 1972; ironically (and unbelievably), just when humans visited the Moon for the last time. We had hoped that the first Moon-landings would lead to a base, and that we would go on to Mars, but for all sorts of reasons (mainly political) this never happened. In 2004 Patrick and I produced a book called ‘Futures: 50 Years in Space,’ celebrating our 50 years together. It was subtitled: ‘The Challenge of the Stars: What we thought then –What we know now.’

I quite often find that younger space artists tell me they were influenced by The Challenge of the Stars, just as I was influenced by The Conquest of Space, and this is a great honour.

‘Mars From Deimos’ 1956. Credit: David A. Hardy. Used by permission. Hardy’s description: ‘The dumbell-shaped spaceship (designed by Arthur C. Clarke) shown in the previous ‘space station’ image has arrived, touching down lightly in the low gravity of Mars’s little outer moon, Deimos. The polar cap is clearly visible, and at that time it was still considered possible that the dark areas on Mars were caused by vegetation, fed by the melting caps. On the right of the planet is Phobos, the inner moon.’

UT: What places on Earth have most inspired your art?

Hardy: I’m a past President (and now European VP) of the International Association of Astronomical Artists (IAAA; http://www.iaaa.org), and we hold workshops in the most ‘alien’ parts of Planet Earth. Through these I have been to the volcanoes of Hawaii and Iceland, to Death Valley CA, the Grand Canyon and Meteor Crater, AZ, to Nicaragua. . . all of these provide not just inspiration but analogues of other worlds like Mars, Io or Triton, so that we can make our work more believable and authentic — as well as more beautiful, hopefully.

UT: How has technology changed how you do your work?

Hardy: I have always kept up with new technology, making use of xeroxes, photography (I used to do all my own darkroom work and processing), and most recently computers. I got an Atari ST with 512k (yes, K!) of RAM in 1986, and my first Mac in 1991. I use Photoshop daily, but I use hardly any 3D techniques, apart from Terragen to produce basic landscapes and Poser for figures. I do feel that 3D digital techniques can make art more impersonal; it can be difficult or impossible to know who created it! And I still enjoy painting in acrylics, especially large works on which I can use ‘impasto’ –laying on paint thickly with a palette knife and introducing textures that cannot be produced digitally!

‘Antares 2’ by David A. Hardy, shows a landscape looking up at the red supergiant star, which we see in Scorpio and is one of the biggest and brightest stars known. It has a small bluish companion, Antares B.

UT: Your new website is a joy to peruse — how does technology/the internet help you to share your work?

Hardy: Thank you. It is hard now to remember how we used to work when we were limited to sending work by mail, or faxing sketches and so on. The ability to send first a low-res jpeg for approval, and then a high-res one to appear in a book or on a magazine cover, is one of the main advantages, and indeed great joys, of this new technology.

UT: I imagine an artist as a person working alone. However, you are part of a group of artists and are involved heavily in the Association of Science Fiction and Fantasy Artists. How helpful is it to have associations with fellow artists?

Hardy: It is true that until 1988, when I met other IAAA artists (both US, Canadian and, then, Soviet, including cosmonaut Alexei Leonov) in Iceland I had considered myself something of a lone wolf. So it was almost like ‘coming out of the closet’ to meet other artists who were on the same wavelength, and could exchange notes, hints and tips.

‘Ice Moon’ by David Hardy. Used by permission.

UT: Do you have a favorite image that you’ve created?

Hardy: Usually the last! Which in this case is a commission for a metre-wide painting on canvas called ‘Ice Moon’. I put this on Facebook, where it has received around 100 comments and ‘likes’ — all favourable, I’m glad to say. It can be seen there on my page, or on my own website, http://www.astroart.org (UT note: this is a painting in acrylics on stretched canvas, with the description,”A blue ice moon of a gas giant, with a derelict spaceship which shouldn’t look like a spaceship at first glance.”)

UT: Anything else you feel is important for people to know about your work?

Hardy: I do feel that it’s quite important for people to understand the difference between astronomical or space art, and SF (‘sci-fi’) or fantasy art. The latter can use a lot more imagination, but often contains very little science — and often gets it quite wrong. I also produce a lot of SF work, which can be seen on my site, and have done around 70 covers for ‘The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction’ since 1971, and many for ‘Analog’. I’m Vice President of the Association of Science Fiction & Fantasy Artists (ASFA; http://www.asfa-art.org ) too. But I always make sure that my science is right! I would also like to see space art more widely accepted in art galleries, and in the Art world in general; we do tend to feel marginalised.

UT: Thank you for providing Universe Today with a more “accurate” banner — we really appreciate your contribution to our site!

Hardy: My pleasure.

See more at Hardy’s website, AstroArt or his Facebook page. Click on any of the images here to go directly to Hardy’s website for more information on each.

Here’s a list of the books Hardy has written and/or illustrated.

The Leonids over Stonhenge by David A. Hardy. Used by permission