Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Building an Interstellar Philosophy

As the AI surge continues, it’s natural to speculate on the broader effects of machine intelligence on deep space missions. Will interstellar flight ever involve human crews? The question is reasonable given the difficulties in propulsion and, just as challenging, closed loop life support that missions lasting for decades or longer naturally invoke. The idea of starfaring as the province of silicon astronauts already made a lot of sense. Thinkers like Martin Rees, after all, think non-biological life is the most likely intelligence we’re likely to find.

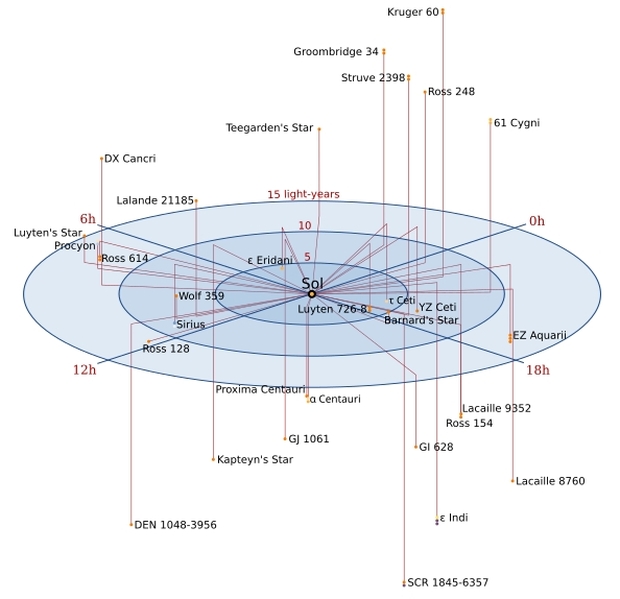

But is this really an either/or proposition? Perhaps not. We can reach the Kuiper Belt right now, though we lack the ability to send human crews there and will for some time. But I see no contradiction in the belief that steadily advancing expertise in spacefaring will eventually find us incorporating highly autonomous tools whose discoveries will enable and nurture human-crewed missions. In this thought, robots and artificial intelligence invariably are first into any new terrain, but perhaps with their help one day humans do get to Proxima Centauri.

An interesting article in the online journal NOĒMA prompts these reflections. Robin Wordsworth is a professor of Environmental Science and Engineering as well as Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard. His musings invariably bring to mind a wonderful conversation I had with NASA’s Adrian Hooke about twenty years ago at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. We had been talking about the ISS and its insatiable appetite for funding, with Hooke pointing out that for a fraction of what we were spending on the space station, we could be putting orbiters around each planet and some of their moons.

Image credit: Manchu.

It’s hard to argue with the numbers, as Wordsworth points out that the ISS has so far cost many times more than Hubble or the James Webb Space Telescope. It is, in fact, the most expensive object ever constructed by human beings, amounting thus far to something in the range of $150 billion (the final cost of ITER, by contrast, is projected at a modest $24 billion). Hooke, an aerospace engineer, was co-founder of the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems (CCSDS) and was deeply involved in the Apollo project. He wasn’t worried about sending humans into deep space but simply about maximizing what we were getting out of the dollars we did spend. Wordsworth differs.

In fact, sketching the linkages between technologies and the rest of the biosphere is what his essay is about. He sees a human future in space as essential. His perspective moves backward and forward in time and probes human growth as elemental to space exploration. He puts it this way:

Extending life beyond Earth will transform it, just as surely as it did in the distant past when plants first emerged on land. Along the way, we will need to overcome many technical challenges and balance growth and development with fair use of resources and environmental stewardship. But done properly, this process will reframe the search for life elsewhere and give us a deeper understanding of how to protect our own planet.

That’s a perspective I’ve rarely encountered at this level of intensity. A transformation achieved because we go off planet that reflects something as fundamental as the emergence of plants on land? We’re entering the domain of 19th Century philosophy here. There is precedent in, for example, the Cosmism created by Nikolai Fyodorov in the 19th Century, which saw interstellar flight as a simple necessity that would allow human immortality. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky embraced these ideas but welded them into a theosophy that saw human control over nature as an almost divine right. As Wordsworth notes, here the emphasis was entirely on humans and not any broader biosphere (and some of Tsiolkovsky’s writings on what humans should do to nature are unsettling}.

But getting large numbers of humans off planet is proving a lot harder than the optimists and dreamers imagined. The contrast between Gerard O’Neill’s orbiting arcologies and the ISS is only one way to make the point. As we’ve discussed here at various times, human experiments with closed loop biological systems have been plagued with problems. Wordsworth points to the concept of the ‘ecological footprint,’ which makes estimates of how much land is required to sustain a given number of human beings. The numbers are daunting:

Per-person ecological footprints vary widely according to income level and culture, but typical values in industrialized countries range from 3 to 10 hectares, or about 4 to 14 soccer fields. This dwarfs the area available per astronaut on the International Space Station, which has roughly the same internal volume as a Boeing 747. Incidentally, the total global human ecological footprint, according to the nonprofit Global Footprint Network, was estimated in 2014 to be about 1.7 times the Earth’s entire surface area — a succinct reminder that our current relationship with the rest of the biosphere is not sustainable.

As I interpret this essay, I’m hearing optimism that these challenges can be surmounted. Indeed, the degree to which our Solar System offers natural resources is astonishing, both in terms of bulk materials as well as energy. The trick is to maintain the human population exploiting these resources, and here the machines are far ahead of us. We can think of this not simply as turning space over to machinery but rather learning through machinery what we need to do to make a human presence there possible in longer timeframes.

As for biological folk like ourselves, moving human-sustaining environments into space for long-term occupation seems a distinct possibility, at least in the Solar System and perhaps farther. Wordsworth comments:

…the eventual extension of the entire biosphere beyond Earth, rather than either just robots or humans surrounded by mechanical life-support systems, seems like the most interesting and inspiring future possibility. Initially, this could take the form of enclosed habitats capable of supporting closed-loop ecosystems, on the moon, Mars or water-rich asteroids, in the mold of Biosphere 2. Habitats would be manufactured industrially or grown organically from locally available materials. Over time, technological advances and adaptation, whether natural or guided, would allow the spread of life to an increasingly wide range of locations in the solar system.

Creating machines that are capable of interstellar flight from propulsion to research at the target and data return to Earth pushes all our limits. While Wordsworth doesn’t address travel between stars, he does point out that the simplest bacterium is capable of growth. Not so the mechanical tools we are so far capable of constructing. A von Neumann probe is a hypothetical constructor that can make copies of itself, but it is far beyond our capabilities. The distance between that bacterium and current technologies, as embodied for example in our Mars rovers, is vast. But machine evolution surely moves to regeneration and self-assembly, and ultimately to internally guided self-improvement. Such ‘descendants’ challenge all our preconceptions.

What I see developing from this in interstellar terms is the eventual production of a star-voyaging craft that is completely autonomous, carrying our ‘descendants’ in the form of machine intellects to begin humanity’s expansion beyond our system. Here the cultural snag is the lack of vicarious identification. A good novel lets you see things through human eyes, the various characters serving as proxies for yourself. Our capacity for empathizing with the artilects we send to the stars is severely tested because they would be non-biological. Thus part of the necessary evolution of the starship involves making our payloads as close to human as possible, because an exploring species wants a stake in the game it has chosen to play.

We will need machine crewmembers so advanced that we have learned to accept their kind as a new species, a non-biological offshoot of our own. We’re going to learn whether empathy with such beings is possible. A sea-change in how we perceive robotics is inevitable if we want to push this paradigm out beyond the Solar System. In that sense, interstellar flight will demand an extension of moral philosophy as much as a series of engineering breakthroughs.

The October 27 issue of The New Yorker contains Adam Kirsch’s review of a new book on Immanuel Kant by Marcus Willaschek, considered a leading expert on Kant’s era and philosophy. Kant believed that humans were the only animals capable of free thought and hence free will. Kirsch adds this:

…the advance of A.I. technology may soon put an end to our species’ monopoly on mind. If computers can think, does that mean that they are also free moral agents, worthy of dignity and rights? Or does it mean, on the contrary, that human minds were never as free as Kant believed—that we are just biological machines that flatter ourselves by thinking we are something more? And if fundamental features of the world like time and space are creations of the human mind, as Kant argued, could artificial minds inhabit entirely different realities, built on different principles, that we will never fully understand?

My thought is that if Wordsworth is right that we are seeing a kind of co-evolution at work – human and machine evolution accelerated by expansion into this new environment – then our relationship with the silicon beings we need will demand acceptance of the fact that consciousness may never be fully measured. We have yet to arrive at an accepted understanding of what consciousness is. Most people I talk to see that as a barrier. I’m going to see it as a challenge, because our natures make us explorers. And if we’re going to continue the explorations that seem part of our DNA, we’re now facing a frontier that’s going to demand consensual work with beings we create.

Will we ever know if they are truly conscious? I don’t think it matters. If I’m right, we’re pushing moral philosophy deeply into the realm of the non-biological. The philosophical challenge is immense, and generative.

The article is Wordsworth, “The Future of Space is More Than Human,” in the online journal NOĒMA, published by the Berggruen Institute and available here.

Jupiter’s Impact on the Habitable Zone

I’ve been thinking about how useful objects in our own Solar System are when we compare them to other stellar systems. Our situation has its idiosyncrasies and certainly does not represent a standard way for planetary systems to form. But we can learn a lot about what is happening at places like Beta Pictoris by studying what we can work out about the Sun’s protoplanetary disk and the factors that shaped it. Illumination can come about in both directions.

Think about that famous Voyager photograph of Earth, now the subject of an interesting new book by Jon Willis called The Pale Blue Data Point (Princeton, 2025). I’m working on this one and am not yet ready to review it, but when I do I’ll surely be discussing how the best we can do at studying a living terrestrial planet at a considerable distance is our own planet from 6 billion kilometers. We’ll use studies of the pale blue dot to inform our work with new instrumentation as we begin to resolve planets of the terrestrial kind.

But let’s look much further out, and a great deal further back in time. A 2003 detection at Beta Pictoris led eventually to confirmation of a planet in the early stages of formation there. Probing how exoplanets form is an ongoing task stuffed with questions and sparkling with new observations. As with every other aspect of exoplanet research, things are moving quickly in this area. Perhaps 25 million years old, this system offers information about the mechanisms involved in the early days of our own. Here on Earth, we also get the benefit of meteorites delivering ancient material for our inspection.

The role of Jupiter in shaping the protoplanetary disk is hard to miss. We’re beginning to learn that planetesimals, which are considered the building blocks of planets, did not form simultaneously around the Sun, and the mechanisms now coming into view affect any budding planetary system. In new work out of Rice University, senior author André Izidoro and graduate student Baibhav Srivastava have gone to work on dust evolution and planet formation using computer simulations that analyze the isotopic variation among meteorites as clues to a process that may be partially preserved in carbonaceous chondrites.

Image: Enhanced image of Jupiter by Kevin M. Gill (CC-BY) based on images provided courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS (Credit: NASA).

The authors posit that dense bands of planetesimals, created by the gravitational effects of the early-forming Jupiter, were but the second generation of such objects in the system’s history. The earlier generation, whose survivors are noncarbonaceous (NC) magmatic iron meteorites, seems to have formed within the first million years. Some two to three million years would pass before the chondrites formed, containing within themselves calcium-aluminum–rich inclusions from that earlier time. The rounded grains called ‘chrondules’ contain once molten silicates that help to preserve that era.

The key fact: Meteorites from objects that formed during the first generation of planetesimal formation melted and differentiated, making retrieval of their original composition problematic. Chondrites, which formed later, better preserve dust from the early Solar System and also contain distinctive ‘chondrules,’ which solidified after going through an early molten state. But the very presence of this isotopic variation demands explanation. From the paper:

…the late accretion of a planetesimal population does not appear readily compatible with a key feature of the Solar System: its isotopic dichotomy. This dichotomy—between NC and carbonaceous (CC) meteorites —is typically attributed to an early and persistent separation between inner and outer disk reservoirs, established by the formation of Jupiter or a pressure bump. In this framework, Jupiter (or a pressure bump) acts as a barrier that prevents the inward drift of pebbles from the outer disk and mixing, preserving isotopic distinctiveness.

But this ‘barrier’ would also seem to prevent small solids moving inwards to the inner disk, so the question becomes, how did enough material remain to allow the formation of early planetesimals at the later era of the chondrites? What is needed is a way to ‘re-stock’ this reservoir of material. Hence this paper. The authors hypothesize a ‘replenished reservoir’ of inner disk materials gravitationally gathered in the gaps in the disk opened up by Jupiter. The accretion of the chondrites and the locations where the terrestrial planets formed are interconnected as the early disk is shaped by the gas giant.

André Izidoro (Rice University) is senior author of the paper:

“Chondrites are like time capsules from the dawn of the solar system. They have fallen to Earth over billions of years, where scientists collect and study them to unlock clues about our cosmic origins. The mystery has always been: Why did some of these meteorites form so late, 2 to 3 million years after the first solids? Our results show that Jupiter itself created the conditions for their delayed birth.”

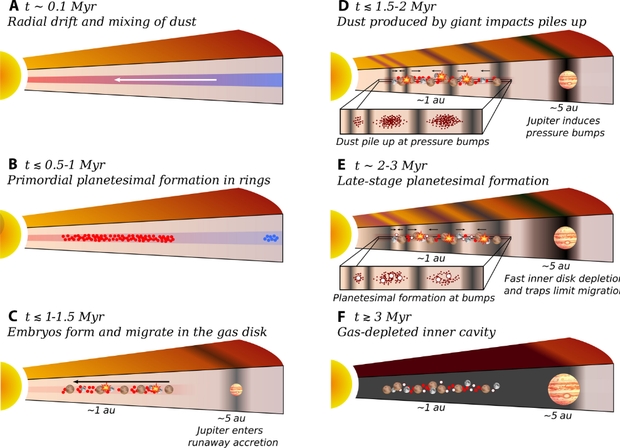

Image: This is Figure 1 from the paper. Caption: Schematic illustration of the proposed evolutionary scenario for the early inner Solar System over the first ~3 Myr. (A) At early times (t ~ 0.1 Myr), radial drift and turbulent mixing transport dust grains across the disk. (B) Around ≲ 0.t to 1 Myr, primordial planetesimal formation occurs in rings. (C) By ~1.5 Myr, growing planetary embryos start to migrate inward under the influence of the gaseous protoplanetary disk, whereas Jupiter’s core enters rapid gas accretion phase. (D) Around ~2 Myr, Jupiter’s gravitational perturbations excite spiral density waves, inducing pressure bumps in the inner disk. Giant impacts among migrating embryos generate additional debris. Pressure bumps act as dust traps, halting inward drift of small solids and leading to dust accumulation. (E) Between ~2 and 3 Myr, dust accumulation at pressure bumps leads to the formation of a second generation of planetesimals. Rapid gas depletion in the inner disk, combined with the presence of these traps, limits the inward migration of growing embryos. (F) By ~3 Myr, the inner gas disk is largely dissipated, resulting in a system composed of terrestrial embryos and a second generation of planetesimals—potentially the parent bodies of ordinary and enstatite chondrites—whereas the inner disk evolves into a gas-depleted cavity.

A separation between material from the outer Solar System and the inner regions preserved the distinctive isotopic signatures in the two populations. Opening up this gap, according to the authors, enabled regions where new planetesimals could grow into rocky worlds. Meanwhile, the presence of the gas giant also prevented the flow of gaseous materials toward the inner system, suppressing what might have been migration of young planets like ours toward the Sun. These are helpful simulations in that they sketch a way for planetesimals to form without being drawn into our star, but there are broad issues that remain unanswered here, as the paper acknowledges:

Our simulations demonstrate that Jupiter’s induced rapid inner gaseous disk depletion, gaps, and rings are broadly consistent with both the birthplaces of the terrestrial planets and the accretion ages of the parent bodies of NC chondrites. Our results suggest that Jupiter formed early, within ~1.5 to 2 Myr of the Solar System’s onset, and strongly influenced the inner disk evolution….

And here is reason for caution:

…we…neglect the effects of Jupiter’s gas-driven migration. This simplification is motivated by the fact that, once Jupiter opens a deep gap in a low-viscosity disk, its migration is expected to be fairly slow, particularly as the inner disk becomes depleted. Simulations show that, in low-viscosity disks, migration can be halted or reversed depending on the local disk structure. In reality, Jupiter probably formed beyond the initial position assumed in our simulations and first migrated via type I migration and eventually entered in the type II regime… but its exact migration history is difficult to constrain.

The authors thus guide the direction of future research into further consideration of Jupiter’s migration and its effects upon disk dynamics. Continuing study of young disks like that afforded by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and other telescopes will help to clarify the ways in which disks can spawn first gas giants and then rocky worlds.

The paper is Srivastava & Izidoro, “The late formation of chondrites as a consequence of Jupiter-induced gaps and rings,” Science Advances Vol. 11, No. 43 (22 October 2025). Full text.

Interstellar Mission to a Black Hole

We normally think of interstellar flight in terms of reaching a single target. The usual destination is one of the Alpha Centauri stars, and because we know of a terrestrial-mass planet there, Proxima Centauri emerges as the best candidate. I don’t recall Proxima ever being named as the destination Breakthrough Starshot officially had in mind, but there is such a distance between it (4.2 light years) and the next target, Barnard’s Star at some 5.96 light years, that it seems evident we will give the nod to Proxima. If, that is, we decide to go interstellar.

Let’s not forget, though, that if we build a beaming infrastructure either on Earth or in space that can accelerate a sail to a significant percentage of lightspeed, we can use it again and again. That means many possible targets. I like the idea of exploring other possibilities, which is why Cosimo Bambi’s ideas on black holes interest me. Associated with Fudan University in Shanghai as well as New Uzbekistan University in Tashkent, Bambi has been thinking about the proliferation of black holes in the galaxy, and the nearest one to us. I’ve been pondering his notions ever since reading about them last August.

Black holes are obviously hard to find as we scale down to solar mass objects, and right now the closest one to us is GAIA-BH1, some 1560 light years out. But reading Bambi’s most recent paper, I see that one estimate of the number of stellar mass black holes in our galaxy is 1.4 X 109. Bambi uses this number, but as we might expect, estimates vary widely, from 10 million to 1 billion. These numbers are extrapolated from the population of massive stars and to a very limited extent on clues from observational astronomy.

Image: The first image of Sagittarius A*, or Sgr A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy. Given how hard it was to achieve this image, can we find ways to locate far smaller solar-mass black holes, and possibly send a mission to one? Credit: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

Bambi calculates a population of 1 black hole and 10 white dwarfs for every 100 stars in the general population. If he’s anywhere close to right, a black hole might well exist within 20 to 25 light years, conceivably detected in future observations by its effects upon the orbital motion of a companion star, assuming we are so lucky as to find a black hole in a binary system. The aforementioned GAIA-BH1 is in such a system, orbiting a companion star.

Most black holes, though, are thought to be isolated. One black hole (OGLE-2011-BLG-0462) has been detected through microlensing, and perhaps LIGO A+, the upgrade to the two LIGO facilities in Hanford, Washington, and Livingston, Louisiana, can help us find more as we increase our skills at detecting gravitational waves. There are other options as well, as Bambi notes:

Murchikova & Sahu (2025) proposed to use observational facilities like the Square Kilometer Array (SKA), the Atacama Large Millimiter/Submillimiter Array (ALMA), and James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Isolated black holes moving through the interstellar medium can accrete from the interstellar medium itself and such an accretion process produces electromagnetic radiation. Murchikova & Sahu (2025) showed that current observational facilities can already detect the radiation from isolated black holes in the warm medium of the Local Interstellar Cloud within 50 pc of Earth, but their identification as accreting black holes is challenging and requires multi-telescope observations.

If we do find a black hole out there at, say, 10 light years, we now have a target for future beamed sailcraft that offers an entirely different mission concept. We’re now probing not simply an unknown planet, but an astrophysical object so bizarre that observing its effects on spacetime will be a primary task. Sending two nanocraft, one could observe the other as it approaches the black hole. A signal sent from one to the other will be affected by the spacetime metric – the ‘geometry’ of spacetime – which would give us information about the Kerr solution to the phenomenon. The latter assumes a rotating black hole, whereas other solutions, like that of Schwarzschild, describe a non-rotating black hole.

Also intriguing is Bambi’s notion of testing fundamental constants. Does atomic physics change in gravitational fields this strong? There have been some papers exploring possible variations in fundamental constants over time, but little by way of observation studying gravitational fields much stronger than white dwarf surfaces. Two nanocraft in the vicinity of a black hole may offer a way to emit photons whose energies can probe the nature of the fine structure constant. The latter sets the interactions between elementary charged particles.

For that matter, is a black hole inevitably possessed of an event horizon, or is it best described as an ‘horizonless compact object’ (Bambi’s term)?

In the presence of an event horizon, the signal from nanocraft B should be more and more redshifted (formally without disappearing, as an observer should never see a test-particle crossing the event horizon in a finite time, but, in practice, at some point the signal leaves the sensitivity band of the receiver on nanocraft A). If the compact object is a Kerr black hole, we can make clear predictions on the temporal evolution of the signal emitted by nanocraft B. If the compact object is a fuzzball [a bound state without event horizon], the temporal evolution of the signal should be different and presumably stop instantly when nanocraft B is converted into fuzzball degrees of freedom.

There are so many things to learn about black holes that it is difficult to know where to begin, and I suspect that if many of our space probes have returned surprising results (think of the remarkable ‘heart’ on Pluto), a mission to a black hole would uncover mysteries and pose questions we have yet to ask. What an intriguing idea, and to my knowledge, no one else has made the point that if we ever reach the level of launching a mission to Proxima Centauri, we should be capable of engineering the same sort of flyby of a nearby black hole.

And on the matter of small black holes, be aware of a just released paper examining the role of dark matter in their formation. This one considers black holes on a much smaller scale, possibly making the chances of finding a nearby one that much greater. Let me quote the abstract (the italics are mine). The citation is below:

Exoplanets, with their large volumes and low temperatures, are ideal celestial detectors for probing dark matter (DM) interactions. DM particles can lose energy through scattering with the planetary interior and become gravitationally captured if their interaction with the visible sector is sufficiently strong. In the absence of annihilation, the captured DM thermalizes and accumulates at the planet’s center, eventually collapsing into black holes (BHs). Using gaseous exoplanets as an example, we demonstrate that BH formation can occur within an observable timescale for superheavy DM with masses greater than 106 GeV and nuclear scattering cross sections. The BHs may either accrete the planetary medium or evaporate via Hawking radiation, depending on the mass of the DM that formed them. We explore the possibility of periodic BH formation within the unconstrained DM parameter space and discuss potential detection methods, including observations of planetary-mass objects, pulsed high-energy cosmic rays, and variations in exoplanet temperatures. Our findings suggest that future extensive exoplanet observations could provide complementary opportunities to terrestrial and cosmological searches for superheavy DM.

The paper is Bambi, “An interstellar mission to test astrophysical black holes,” iScience Volume 28, Issue 8113142 (August 15, 2025). Full text. The paper on black holes and dark matter is Phoroutan-Mehr & Fetherolf, “Probing superheavy dark matter with exoplanets,” Physical Review D Vol. 112 (20 August 2025), 036012 (full text).

Teegarden’s Star b: A Habitable Red Dwarf Planet?

I have a number of things to say about Teegarden’s Star and its three interesting planets, but I want to start with the discovery of the star itself.

Here we have a case of a star just 0.08 percent as massive as the Sun, an object which is all but in brown dwarf range and thus housing temperatures low enough to explain why, despite its proximity, it took until 2003 to find it.

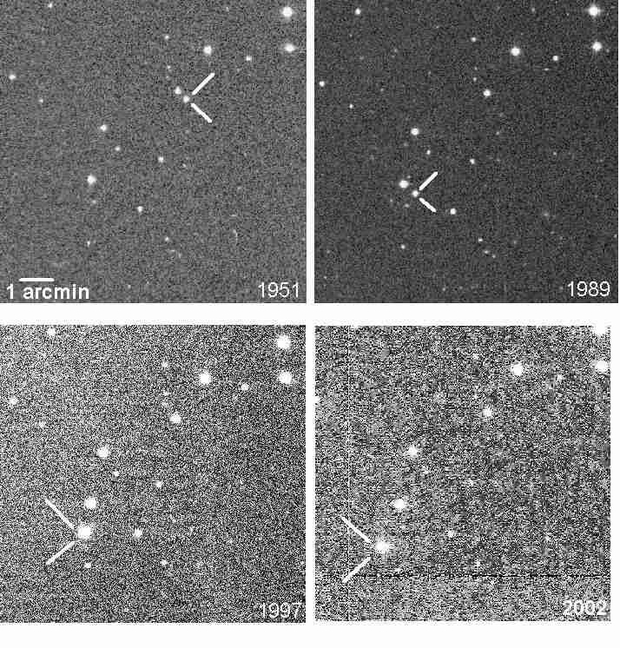

Moreover, conventional telescopes were not the tools of discovery but archival data. Bonnard Teegarden (NASA GSFC) dug into archival data from the Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking program, surmising that there ought to be more small stars near us than we were currently seeing. The data mining paid off, and then paid off again when the team looked at the Palomar Sky Survey of 1951. This was a team working without professional astronomers and telescopes.

Image: Teegarden’s Star was subsequently identified in astronomical images taken more than 50 years ago. Credit: Palomar Sky Survey / SolStation.com.

That it took until 2019 to announce evidence of planets reflects the fact that for some time, we had trouble even coming up with a workable parallax reading, one that finally produced a distance of 12.497 light years. There are no transits at Teegarden’s Star, so the discovery data on the first two planets came through radial velocity studies conducted with the CARMENES instrument at the Calar Alto Observatory in Spain. In 2024 a third planet was found, likewise by RV.

Teegarden’s Star compels attention because of those planets, and in particular Teegarden’s Star b, which orbits just inside the habitable zone with an orbit lasting about five days. Its minimum mass, calculated from the radial velocity data, is 1.05 times that of Earth, but recall that because of the limitations of the RV method, we can’t know the orbital inclination of a world that is likely larger. The primary is relatively quiescent by red dwarf standards, and indeed produces flares that would not be problematic if planet b retained an atmosphere.

That last note is important, because the whole question of how long the planets of young red dwarfs retain an atmosphere is crucial. Teegarden’s Star is about eight billion years old and, as I mention, comparatively calm. But young red dwarfs can spit out enormous flares and present serious problems for atmospheric gases, to the point that the atmospheres may be depleted or destroyed altogether. We need to come to grips with the possibility that red dwarfs may simply be inhospitable to life, a notion skillfully dissected by David Kipping in a recent paper that I plan to address in the near future.

For now, though, let’s take a brief look at a new paper from Ryan Boukrouche and Rodrigo Caballero (Stockholm University) and Neil Lewis (University of Exeter). The authors tackle climate and potential habitability of Teegarden’s Star b, noting that its proximity puts it in the catalog for study by next-generation observatories. The team uses a three-dimentional global climate model (GCM) to study habitability, including position in the habitable zone and the question of surface climate if there is an Earth-like atmosphere.

The interest in Teegarden’s Star draws not only from its Earth-mass planets – which Boukrouche and colleagues see as prime fodder for future telescopes like the ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope and its Planetary Camera and Spectrograph – but the effect of flare activity on atmospheres. The authors assume that Teegarden’s Star b is tidally locked given its tight orbit (4.9 days) around the primary. They consider values for surface albedo which approximate first an ocean-dominated surface and then a surface dominated by land masses. Here the discussion reaches this conclusion: “Although the sensitivity to surface albedo is… relatively small, it illustrates that the habitable zone does depend on factors intrinsic to the planet, not just on orbital parameters.”

The results indicate that this intriguing planet may be habitable under these atmosphere assumptions, but if so, it is still close to the inner edge of the habitable zone. Indeed, of two different orbital distances chosen from earlier papers investigating this planet, one produces a runaway greenhouse effect that would prevent the presence of liquid water on the surface. Fittingly, the authors are sensitive to the fact that the habitability question hinges upon the configuration of their models. Citing studies of TRAPPIST-1, they note this:

…different GCMs configured to simulate the same planet can produce a range of climates and circulation regimes (presumably owing to differences between the parameterizations included in each model). For example, models capable of consistently simulating non-dilute atmospheres may explore the possibility that under a range of instellation values, the planet’s atmosphere might be in a moist greenhouse state (Kasting et al. 1984) instead of a runaway, where water builds up enough that the stratosphere becomes moist, driving photodissociation and loss of water to space.

Installation is critical. The classic problem: We need more data, which can only be supplied by future telescopes. Teegarden’s Star remains highly interesting, but if we have yet to nail down the orbital distance of a planet so close to the inner edge of the habitable zone, we can’t yet make the call on how much light and heat this planet receives. And the authors themselves point out that the origins of nitrogen on Earth are not completely understood, which makes guesses at its abundance in other worlds’ atmospheres problematic.

Image: Even in our local ‘neighborhood,’ the data on Earth-mass planets is paltry, and our investigations rely heavily on simulations with values plugged in to gauge the possibilities. New instrumentation will help but it’s sobering to realize how far we are from making the definitive call on such basic issues as whether a given rocky world even has an atmosphere. Image credit: Inductiveload – self-made, Mathematica, Inkscape. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Let me just suggest that this is where we are right now when it comes to key questions about life around nearby stars. Plugging in the necessary data on any system takes time and, when it comes to Earth-mass planets around red dwarfs, the kind of instrumentation that is still on the drawing boards or in some cases under construction. Given all that, we’re going to have quite a few years ahead of us in which we’re constructing theories to explain what we see without the solid data that will help us choose among myriad alternatives.

The paper is Boukrouche, Caballero & Lewis, “Near the Runaway: The Climate and Habitability of Teegarden’s Star b,” accepted at The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Preprint available.

A Dark Object or ‘Dark Matter’?

We are fortunate enough to be living in the greatest era of discovery in the history of our species. Astronomical observations through ever more sensitive instruments are deepening our view of the cosmos, and just as satisfyingly, forcing questions about its past and uncertain future. I’d much rather live in a universe with puzzling signs of accelerated expansion (still subject to robust debate) and evidence of matter that does not interact with the electromagnetic force (dark matter) than in one I could completely explain.

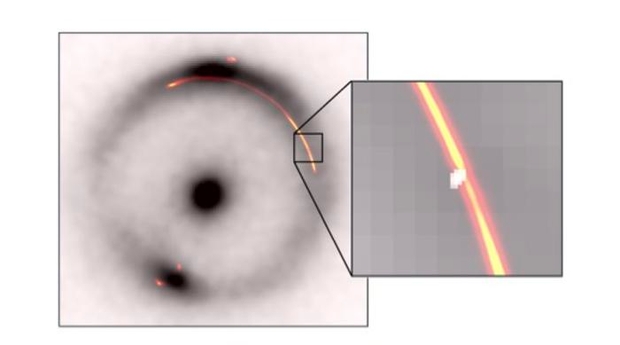

Thus the sheer enjoyment of mystery, a delight accented this morning as I contemplate the detection of a so-called ‘dark object’ of unusually low mass. Presented in both Nature Astronomy and Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, the papers describe an object that could only be detected through gravitational lensing, a familiar exoplanet detection tool that reshapes light passing near it. With proper analysis, the nature of the distortion can produce a solid estimate of the amount of matter involved.

Image: The black ring and central dot show an infrared image of a distant galaxy distorted by a gravitation lens. Orange/red shows radio waves from the same object. The inset shows a pinch caused by another, much smaller, dark gravitational lens (white blob). Credit: Devon Powell, Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics.

We wouldn’t have any notion of dark matter were it not for the fact that while we cannot see it via photons, it does interact with gravity, and was indeed first hypothesized because of the anomalous rotation of distant galaxies. Fritz Zwicky was making conjectures about the Coma Cluster of galaxies way back in the 1930s, while Jan Oort pondered mass and observed motion of the Milky Way’s stars in the same period. It would be Vera Rubin in the 1970s who reawakened the study of dark matter, with her observations of stellar rotation around galactic centers, which proved to be too fast to be explained without additional mass, meaning mass that we currently couldn’t see.

The present work involves the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, the Very Long Baseline Array in Hawaii and the European Very Long Baseline Interferometric Network, which creates a virtual telescope the size of Earth. Heavy-hitter instrumentation for sure, and all of it necessary to spot the infinitesimal signals of the gravitational lensing created by this object.

Devon Powell (Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Germany is lead author of the paper in Nature Astronomy:

“Given the sensitivity of our data, we were expecting to find at least one dark object, so our discovery is consistent with the so-called ‘cold dark matter theory’ on which much of our understanding of how galaxies form is based. Having found one, the question now is whether we can find more and whether the numbers will still agree with the models.”

An interesting question indeed. It raises the question of whether dark matter can exist in regions without any stars, and offers at least a tentative answer. Or will we subsequently learn that this object is something a bit more prosaic, a compact and inactive dwarf galaxy from the very early universe? The authors point out that this is the lowest mass object ever found through gravitational lensing, which points to the likelihood that future searches will uncover other examples. We’re clearly at the beginning of the study of dark matter and remain ignorant of its makeup, so we can expect this work to continue. New lens-modeling techniques and datasets taken at high angular resolution provide the tools needed to make images more detailed than any before taken of the high-redshift universe and gravitationally lensed objects.

From the Powell et al. paper:

Strong gravitational lensing offers a powerful alternative pathway for studying low-mass objects with little to no EM luminosity. A spatially extended source in a galaxy-scale strong lens system acts as a backlight for the gravitational landscape of its lens galaxy, revealing low-mass perturbers through their gravitational effects alone. Furthermore, lens galaxies typically lie in the redshift range 0.2 ≲ z ≲ 1.5, which means that low-mass, low-luminosity objects can be detected and studied across cosmic time. To date, observations of galaxy-scale lenses with resolved arcs have been used to detect three low-mass perturbers: discovered by Hubble, Keck and ALMA…[E]xpanding the mass range that we can robustly probe necessitates that we use strong lens observations at the highest possible angular resolution.

The first paper is Powell et al., “A million-solar-mass object detected at a cosmological distance using gravitational imaging,” Nature Astronomy 4 March 2025. Full text. The second paper is McKean et al., “An extended and extremely thin gravitational arc from a lensed compact symmetric object at redshift of 2.059.” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Vol. 544, Issue 1 (November, 2025), L24-30. Full text.

Solar Sails for Space Weather

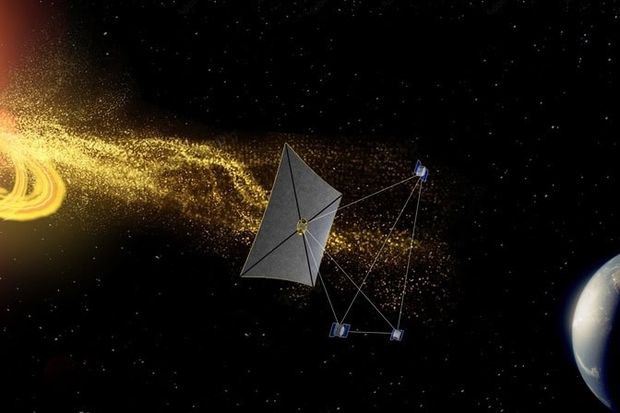

A new paper dealing with solar phenomena catches my eye this morning. Based on work performed at the University of Michigan, it applies computer modeling to delve into what we can call ‘structures’ in the solar wind, which basically means large-scale phenomena like coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and powerful magnetic flux ‘ropes’ that are spawned by the interaction of a CME and solar wind plasma. What particularly intrigues me is a mission concept that the authors put to work here, creating virtual probes to show how our questions about these structures can be resolved if the mission is eventually funded.

More on that paper in a minute, but first let me dig into the mission’s background. It has been dubbed Space Weather Investigation Frontier, or SWIFT. Originally proposed in 2023 in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences and with a follow-up in 2025 in Acta Astronautica (citations below), the mission is the work of Mojtaba Akhavan-Tafti and collaborators at the University of Michigan, Les Johnson (NASA MSFC) and Adam Szabo (NASA GSFC). The latter is a co-author on today’s paper., which studies the use of the SWIFT probes to study large-scale solar activity.

What SWIFT would offer is the ability to monitor solar activity at a new level of detail through multiple space weather stations. A solar sail is crucial to the concept, for one payload must be placed closer to the Sun than the L1 Lagrange point, where gravitational equilibrium keeps a satellite in a fixed position relative to Sun and Earth. Operating closer to the Sun than L1 requires a solar sail that can exactly balance the momentum of solar photons and the gravitational force pulling it inward. If this ‘statite’ idea sounds familiar, it’s because the work grows out of NASA’s Solar Cruiser sail, a quadrant of which was successfully deployed last year on Earth. We’ve discussed Solar Cruiser in relation to the study of the Sun’s high latitudes using non-Keplerian orbits.

Image: An artist’s rendering of the spacecraft in the SWIFT constellation stationed in a triangular pyramid formation between the sun and Earth. A solar sail allows the spacecraft at the pyramid’s tip to hold station beyond L1 without conventional fuel. Credit: Steve Alvey, University of Michigan.

The SWIFT mission, unlike Solar Cruiser, would consist of four satellites – one of them using a large sail, and the other three equipped for chemical propulsion. Think of a triangular pyramid, with the sail-equipped probe at the top and the other three probes at each corner of the base in a plane around L1. Most satellites tracking Solar activity are either in low-Earth orbit or geosynchronous orbit, while current assets at the L1 point (WIND, ACE, DSCOVR, and IMAP) can offer up to 40 minutes of advance warning for dangerous solar events.

SWIFT would buy us more time, which could be used to raise satellite orbits that would be compromised by the increased drag caused by atmospheric heating during a geomagnetic storm. Astronauts likewise would receive earlier warning to take cover. But the benefits of this mission design go beyond small increases in alert time. With an approximate separation of up to 1 solar radius, the SWIFT probes would be able to extract data from four distinct vantage points.

Designed to fit the parameters of a Medium-Class Explorer mission, SWIFT is described in the Johnson et al. paper in Acta Astronautica as a ‘hub’ spacecraft (sail-equipped) with three ‘node’ spacecraft, all to be launched aboard a Falcon 9. The craft will fly “in an optimized tetrahedron constellation, covering scales between 10 and 100s of Earth radii.” A bit more from the paper:

This viewing geometry will enable scientists to distinguish between local and global processes driving space weather by revealing the spatial characteristics, temporal evolution, and geo-effectiveness of small-to meso-scale solar wind structures and substructures of macro-scale structures, such as interplanetary coronal mass ejections (ICMEs) and stream interaction regions (SIRs). In addition, real time measurements of earth-bound heliospheric structures from sub-L1 will improve our current forecasting lead-times by up to 35 percent.

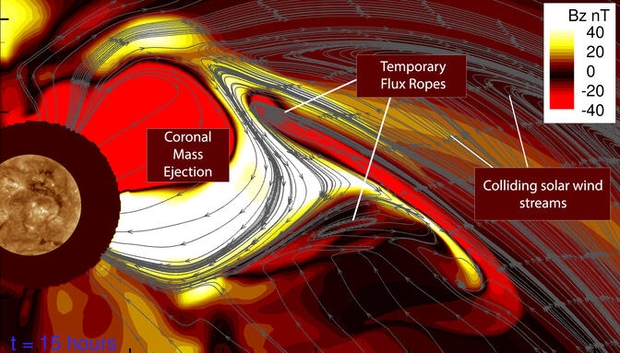

Looking now at the paper “High-resolution Simulation of Coronal Mass Ejection–Corotating Interaction Region Interactions: Mesoscale Solar Wind Structure Formation Observable by the SWIFT Constellation,” with lead author W. B. Manchester, the scale of the potential SWIFT contribution becomes clear::

The radial and longitudinal spacecraft separations afforded by the SWIFT constellation enable analyses of the magnetic coherence and dynamics of meso- to large-scale solar wind structures… The main advantage of the tetrahedral constellation is its ability to distinguish between a structure’s spatial and temporal variations, as well as their orientations.

Coronal mass ejections are huge outbursts of plasma whose injections into the solar wind form mesoscale structures with profound implications for Earth. Magnetic field interactions can produce geomagnetic storms that play havoc with communications and navigation systems. The effects show up in unusual places. Sudden changes in Earth’s atmosphere can affect satellite orbits. On the ground, this particular study, out of the University of Michigan, cites a 2024 geomagnetic event that created large financial losses in agricultural areas in the US Midwest by crippling navigation systems on farm-belt tractors.

Mojtaba Akhavan-Tafti, co-author of the paper, notes the need for more precise detection of this phenomenon:

“If there are hazards forming out in space between the sun and Earth, we can’t just look at the sun. This is a matter of national security. We need to proactively find structures like these Earth-bound flux ropes and predict what they will look like at Earth to make reliable space weather warnings for electric grid planners, airline dispatchers and farmers.”

Flux ropes, between 3,000 and 6 million miles wide, are hard to recreate in current CME simulations and prove too large for existing modeling of magnetic field interactions with plasma. The new study produces a simulation that probes the phenomenon, showing that these ‘ropes’ are produced as the coronal mass ejection moves outward through solar wind plasma, and can form vortices interacting with different streams of solar wind. The authors compare them to tornadoes, noting that existing space weather-monitoring spacecraft are not always able to detect their formation. SWIFT will be able to spot them.

Image: A computer-generated image shows where rotating magnetic fields form at the edges of a coronal mass ejection 15 hours after a solar eruption. The coronal mass ejection is the large bubble extending from the sun at the left edge of the image. Two streams of plasma extend from the edge of the coronal mass ejection as it hits neighboring streams of fast and slow solar wind. Shades of red and yellow depict the strength and orientation of the plasma’s magnetic field (labeled “Bz” in the figure legend). Shades of red represent plasma that could trigger geomagnetic storms if it hits Earth, while shades of yellow represent plasma with a strong, positive orientation. The red-brown circle around the sun shows the area not covered by the simulation, about ten million miles wide. ILLUSTRATION: Chip Manchester, University of Michigan.

This is fascinating research into a topic with near-term ramifications, a matter of planetary defense that we can take steps to resolve soon, although as always we await funding decisions. In the larger perspective, here is another way sails can be employed for purposes no other propulsion method could achieve. Future sails could use these methods to ‘hover’ over the Sun’s polar regions. Moreover, close observation of space weather changes near the Earth has much to tell us about future mission concepts that would harness solar wind plasma to drive a magsail or enable an electric sail to reach high velocities.

ADDENDUM: Alex Tolley tracked down a paper I hadn’t seen on SWIFT, available here. This may be helpful in understanding the full mission concept.

The 2023 paper on SWIFT is Akhavan-Tafti et al., “Space weather investigation Frontier (SWIFT),” Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences Vol 10 (2023), 1185603 (abstract). The 2025 paper is Johnson et al., “Space Weather Investigation Frontier (SWIFT) mission concept: Continuous, distributed observations of heliospheric structures from the vantage points of Sun-Earth L1 and sub-L1,” Acta Astronautica Vol. 236 (November 2025), 684=691 (abstract). The paper on solar activity as a target for SWIFT is Manchester et al., “High-resolution simulation of CME-CIR interactions: small- to mesoscale solar wind structure formation observable by the SWIFT constellation,” The Astrophysical Journal Vol. 992 No. 1 (2025), 51 (full text).