The news from Titan could not be more curious. Radar imagery shows dark areas that may be smooth plains choked with ice, or perhaps pools of liquid methane. The early photographs showed few topographical features, due largely to the diffuse glare that reduces shadows under Titan’s thick atmosphere. But processed radar images showed rough terrain interspersed with darker areas that seem to be flat. Variations in elevation appear to be no more than 150 feet in the area most closely studied, according to this article in the New York Times (free registration required).

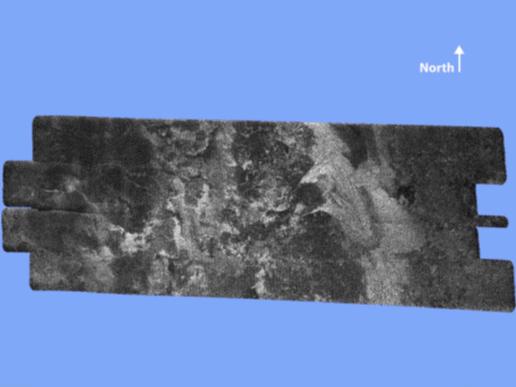

And what are these strange surface streaks in the equatorial region? Early speculation is that they are ridges of ice or deposits of some kind of windblown material.

Image: This medium-resolution view shows some of the surface streaks of Titan’s equatorial terrain. The streaks are oriented roughly east to west; however, some streaks curve to the north and others curve to the south, perhaps due to the topography of this region. North is a few degrees to the right of vertical. The scale is .85 kilometers (.53 miles) per pixel. This image was taken on Oct. 26, 2004, by Cassini’s imaging science subsystem using near-infrared filters. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

From the Times article:

“Dr. Ralph Lorenz of the University of Arizona reported that measurements of Titan’s surface heat ‘were consistent with a surface covered in organic material’ and that the dark regions were richer in organics than the brighter areas…Even though Titan’s mass is estimated to be half water and half rock, any lake would not be liquid water. It would be frozen solid on a surface with temperatures as low as minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit.”

Here’s a San Francisco Chronicle story about Si-Si the Cat, a region of possible lakes (named after a scientist’s daughter noticed it looked like a Halloween cat in the image).

And despite the fact that Titan would surely have received many hits from large objects in its life, no craters were visible in the latest round of images, suggesting that craters have filled in with water ice and what would probably be a rain of hydrocarbons from the sky. Titan’s atmosphere is primarily nitrogen, but methane is also plentiful.

The Cassini team points to the problems with our current view of Titan: the black-and-white radar image covered only 1 percent of the moon’s surface, a strip of land 75 miles wide and 1,250 miles long. An excellent ESA page showing how these images are cleaned up through various digital processing methods can be found here.

Cassini will make 44 more close passes of Titan in the next four years, and Huygens is scheduled to land in January. Assuming Huygens makes it down safely, what will it encounter on the surface? It may well come down in a hydrocarbon brew of methane, propane or butane, but the craft is designed to float, and we may get half an hour or so of data if all goes well. Clearly, we’re only at the beginning of this story.