Keep an eye on ESA’s SMART-1 mission, which recently completed a four-hour burn of its ion engine to correct its trajectory to the Moon. The next engine burn, lasting 4.5 days, won’t occur until November 15 when the craft has reached lunar orbit. The final operational orbit will be polar elliptical, ranging from 300 to 3,000 kilometres above the Moon’s surface. SMART-1 will perform a six-month survey of chemical elements on the lunar surface by way of examining various theories on how the Moon originally formed.

What’s interesting about SMART-1, in addition to the exotic series of spiraling orbits it is using to reach the moon, is its solar-electric propulsion system. This device uses electricity (generated from sunlight through solar panels) to accelerate xenon ions through an electric grid at huge velocity. So-called ‘ion engines’ like this create low thrust, but their specific impulse (ISP) is high. Their efficiency means a spacecraft can carry less fuel and be outfitted with more scientific instruments.

What’s interesting about SMART-1, in addition to the exotic series of spiraling orbits it is using to reach the moon, is its solar-electric propulsion system. This device uses electricity (generated from sunlight through solar panels) to accelerate xenon ions through an electric grid at huge velocity. So-called ‘ion engines’ like this create low thrust, but their specific impulse (ISP) is high. Their efficiency means a spacecraft can carry less fuel and be outfitted with more scientific instruments.

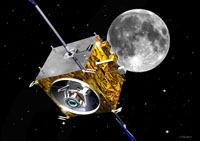

Image: Artist’s impression of SMART-1. Credit: European Space Agency.

You can’t use an ion engine to lift off from a planetary surface; high-thrust, low ISP chemical engines are better for that. But because it can keep pushing for months or even years, that gentle nudge out the back mounts up. On long missions (as, for example, to the outer planets or the Kuiper Belt), an ion engine can operate almost constantly, allowing such designs to outperform chemical rockets.

The first craft to use an operational ion propulsion system in space was NASA’s Deep Space I mission, launched in October of 1998 (although the principle was tested as far back as 1964 on the SERT 1 satellite). Both Deep Space 1 and SMART-1 use the solar-electric variant of ion propulsion, which works well in the inner solar system where sunlight is plentiful. But to reach the outer planets, nuclear-electric engines will be needed to provide the power to ionize the gas atoms.

The upshot: ion propulsion isn’t powerful enough to get us to another star, but it may develop into an efficient way to launch missions to the outer solar system. And it will take a space-based infrastructure to create our first interstellar probes, making ion propulsion one of the enabling technologies upon which more powerful designs will be built.

ESA maintains good Web materials on SMART-1; its home page is here.

test

test test

test test