Each new world we visit offers a different perspective on how planets and their moons form. Consider Saturn’s moon Hyperion, the density of which now appears to be only about 60 percent that of solid water ice. What that means is that much of the moon’s interior — 40 percent or more — is made up of empty space, so that Hyperion is not so much a solid body as a conglomeration of icy rubble.

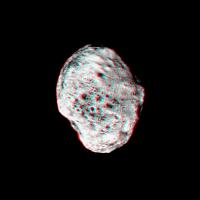

The Hubble images acquired between June 9 and 11 confirm this estimate, showing an object that looks almost sponge-like, bearing the imprint of countless craters which seem relatively recent. What we can gather from all this is that Hyperion is a moon that is pushing a critical limit beyond which the internal pressure of its gravity would start to crush weaker materials, closing up those porous spaces and establishing the more familiar spherical shape of larger bodies. Hyperion’s diameter (adjusting for its irregular shape) is 360 x 280 x 225 km (223 x 174 x 140 miles).

We’ll have a much closer look at Hyperion in September (these images were taken from 815,000 to 168,000 kilometers (506,000 to 104,000 miles); the later flyby will take Cassini within 510 kilometers (317 miles). Until then, you can see a movie sequence of the Hyperion encounter at the Cassini Imaging Central Laboratory for Operations site, showing the jagged outlines that reveal large impacts and the moon’s unusual shape as it tumbles past.

We’ll have a much closer look at Hyperion in September (these images were taken from 815,000 to 168,000 kilometers (506,000 to 104,000 miles); the later flyby will take Cassini within 510 kilometers (317 miles). Until then, you can see a movie sequence of the Hyperion encounter at the Cassini Imaging Central Laboratory for Operations site, showing the jagged outlines that reveal large impacts and the moon’s unusual shape as it tumbles past.

Image: Saturn’s moon Hyperion pops into view in this stereo anaglyph (or 3D view) created from Cassini images. Images taken from slightly different viewing angles allow construction of such stereo views, which are helpful in interpreting the moon’s irregular shape. Craters are visible on the moon’s surface down to the limit of resolution in this image, about 1 kilometer (0.6 mile) per pixel. The fresh appearance of most of these craters, combined with their high spatial density, makes Hyperion look something like a sponge. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

Coming soon for Cassini is another Enceladus flyby, this one the closest yet at 175 kilometers (109 miles). The last time the spacecraft closed on Enceladus, scientists were startled to find a tenuous atmosphere that may imply internal activity on the moon. It is also intriguing that Enceladus is crater-free on large areas of its surface, making its similarities to Europa and Ganymede (both of which may have water beneath their surfaces) worthy of extended study. As I write, we are two days away from the Enceladus encounter.

NASA Finds Hydrocarbons on Saturn’s Moon Hyperion

PASADENA, Calif. – NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has revealed for the first time surface details of Saturn’s moon Hyperion, including cup-like craters filled with hydrocarbons that may indicate more widespread presence in our solar system of basic chemicals necessary for life.

Hyperion yielded some of its secrets to the battery of instruments aboard Cassini as the spacecraft flew close by in September 2005. Water and carbon dioxide ices were found, as well as dark material that fits the spectral profile of hydrocarbons.

A paper appearing in the July 5 issue of Nature reports details of Hyperion’s surface craters and composition observed during this flyby, including keys to understanding the moon’s origin and evolution over 4.5 billion years. This is the first time scientists were able to map the surface material on Hyperion.

“Of special interest is the presence on Hyperion of hydrocarbons–combinations of carbon and hydrogen atoms that are found in comets, meteorites, and the dust in our galaxy,” said Dale Cruikshank, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif., and the paper’s lead author. “These molecules, when embedded in ice and exposed to ultraviolet light, form new molecules of biological significance. This doesn’t mean that we have found life, but it is a further indication that the basic chemistry needed for life is widespread in the universe.”

Cassini’s ultraviolet imaging spectrograph and visual and infrared mapping spectrometer captured compositional variations in Hyperion’s surface. These instruments, capable of mapping mineral and chemical features of the moon, sent back data confirming the presence of frozen water found by earlier ground-based observations, but also discovered solid carbon dioxide (dry ice) mixed in unexpected ways with the ordinary ice.

Images of the brightest regions of Hyperion’s surface show frozen water that is crystalline in form, like that found on Earth.

“Most of Hyperion’s surface ice is a mix of frozen water and organic dust, but carbon dioxide ice is also prominent. The carbon dioxide is not pure, but is somehow chemically attached to other molecules,” explained Cruikshank.

Prior spacecraft data from other moons of Saturn, as well as Jupiter’s moons Ganymede and Callisto, suggest that the carbon dioxide molecule is “complexed,” or attached with other surface material in multiple ways. “We think that ordinary carbon dioxide will evaporate from Saturn’s moons over long periods of time,” said Cruikshank, “but it appears to be much more stable when it is attached to other molecules.”

“The Hyperion flyby was a fine example of Cassini’s multi-wavelength capabilities. In this first-ever ultraviolet observation of Hyperion, the detection of water ice tells us about compositional differences of this bizarre body,” said Amanda Hendrix, Cassini scientist on the ultraviolet imaging spectrograph at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

Hyperion, Saturn’s eighth largest moon, has a chaotic spin and orbits Saturn every 21 days. The July 5 issue of Nature also includes new findings from the imaging team about Hyperion’s strange, spongy-looking appearance. Details are online at: http://ciclops.org/view.php?id=3303 .

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the Cassini-Huygens mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington.

More information on the Cassini mission is available at:

http://www.nasa.gov/cassini