Is science fiction a predictive medium, or is it, as I have opined before in Centauri Dreams, a diagnostic form of writing, telling us more about the times we live in than any purported future it describes? The question is occasioned by SF writer and scholar James Gunn, whose essay “Tales from Tomorrow,” available online and in the August/September issue of Science & Spirit, synopsizes the evolution of science fiction from Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s attempt to “…unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation” to recent work like Greg Egan’s Permutation City, where the mysteries of uploading human personalities into computers take center stage.

Here Gunn discusses the development of the genre in the early magazines, as edited by Hugo Gernsback and the legendary John Campbell:

Here Gunn discusses the development of the genre in the early magazines, as edited by Hugo Gernsback and the legendary John Campbell:

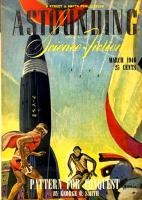

While there were few science fiction books to speak of until 1946, what evolved through magazines like Gernsback’s was a literature of ideas and, more important, a literature of change and anticipation. As a Darwinian fiction that has at its heart a belief in the adaptability of the human species, science fiction itself naturally evolves—and, indeed, science fiction is at its best when it is most innovative. At least for a time, a belief in the power of rationality and the survival—even the dominance—of the human species underpinned most works of science fiction. (This philosophy was most apparent under the stewardship of John W. Campbell Jr., who became editor of Astounding Science Fiction magazine in 1937 and attracted writers like Robert A. Heinlein and Isaac Asimov, who shared his vision.)

Image (above): Science fiction author and critic James Gunn.

Today’s SF, Gunn believes, is less likely to focus on space exploration for its own sake; the genre has likewise moved away from the ‘alien goodwill’ period of the 1970s and ’80s (think Close Encounters of the Third Kind, or E.T.) and into the dark universe of novels like George Zebrowski’s The Killing Star, where life on the galactic level is a matter of destroying other civilizations because they will, acting on their own imperatives, try to destroy you.

Gunn moves through SF utopias and dystopias (emphasizing John Brunner’s extraordinary Stand on Zanzibar, a 1968 novel that uses techniques reminiscent of John Dos Passos) to works on economics and social organization, but he notes that all of these play into the genre’s focus on rapid technological change. “Science fiction,” he writes, “is inextricably linked to the rise of the machine’s role in society; indeed, the origins of science fiction can be traced to the Industrial Revolution and James Watts’ perfection of the steam engine. Science fiction writers have had a love-hate relationship with machinery ever since. As C.P. Snow noted in his famous “Two Cultures” lectures, literary authors feared the machine, while science fiction writers either embraced it or approached with caution.”

Given all that, it’s ironic how poorly science fiction anticipated the computer; most of the classic works growing out of computer networking come well after the technology had demonstrated its powers, even William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984), which was written at a time when the capabilities demonstrated by the ARPANET had already begun to take hold in university networks. Few stories presage the emergence of computing power on the home desktop (a surprising exception: Murray Leinster’s 1946 story “A Logic Named Joe.”) The certainties of scientific progress have given way, in Gunn’s view, to a questioning about the role of science itself, a natural part of the evolution of a field that he believes is always marked by change.

Gunn’s apparent belief that other genres — the detective story, the romance, the western — do not themselves evolve is perplexing. All it takes is one Ruth Rendell novel to demonstrate how lively and malleable the mystery genre remains, while thriller enthusiasts have only to check Martin Cruz Smith’s superb December 6 to see how genre conventions can be refreshed and reshaped. Perhaps Gunn’s essay is itself diagnostic, for it demonstrates a certain widely-held complacency of outlook among SF practitioners that some of us think restrains rather than elevates the field. If so, it’s a rare misstep for Gunn, who remains the greatest living scholar of science fiction and one of its most capable contributors.

Gunn’s apparent belief that other genres — the detective story, the romance, the western — do not themselves evolve is perplexing. All it takes is one Ruth Rendell novel to demonstrate how lively and malleable the mystery genre remains, while thriller enthusiasts have only to check Martin Cruz Smith’s superb December 6 to see how genre conventions can be refreshed and reshaped. Perhaps Gunn’s essay is itself diagnostic, for it demonstrates a certain widely-held complacency of outlook among SF practitioners that some of us think restrains rather than elevates the field. If so, it’s a rare misstep for Gunn, who remains the greatest living scholar of science fiction and one of its most capable contributors.

Image: The March, 1946 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, containing Murray Leinster’s “A Logic Named Joe” (written under his pseudonym Will F. Jenkins). Astounding led the field in its day with an emphasis on rationality and a fascination with pushing scientific method to its limits to uncover new technologies.