A meteor impact greater than the one that killed the dinosaurs? That’s the word from Antactica, where scientists working in the Wilkes Land region have found a crater twice the size of the Chicxulub crater in the Yucatan, which was likely the blow that led to the dinosaurs’ demise some 65 million years ago. “This Wilkes Land impact is much bigger than the impact that killed the dinosaurs, and probably would have caused catastrophic damage at the time,” said Ralph von Frese, a professor of geological sciences at Ohio State University.

Finding such a crater beneath the frozen wastes of Antartica isn’t an easy proposition, but tapping the GRACE satellites made the difference. GRACE stands for Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment; it’s a duo of satellites sent into orbit in March of 2002, each flying about 220 kilometers apart in a polar orbit 500 kilometers high. The GRACE experiment maps Earth’s gravity by taking measurements of the distance between the satellites using GPS and microwave ranging.

Out of that you get the ability to examine extremely subtle effects like deep currents in the ocean or movement between ice sheets and surrounding water. You also get to peer beneath the ice of Antarctica, where von Frese and team found a 200-mile plug of mantle material that had risen from deep below. Known as ‘mascons,’ such concentrations of mass form when large objects strike the planet, driving dense mantle material up into the overlying crust.

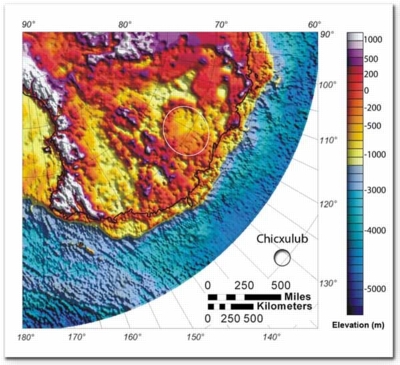

Matching their gravity data with airborne radar images, the team found a crater some 300 miles wide, with the mascon at dead center. The fact that the concentration of mass is still present tells us that the crater formed relatively recently in geological terms, perhaps some 250 million years ago. Is this the blow that began the breakup of the super-continent Gondwana by opening a rift valley that pushed Australia to the north? No one knows, but because the rift cuts through the crater, the possibility cannot be ruled out.

Image: Airborne radar image of land elevation in East Antarctica. Higher elevations appear red, purple, and white; the location of the Wilkes Land crater is circled (above center). An inset of the Chicxulub crater is included for comparison. Credit: Ohio State University.

Another possible correlation: the crater may have formed at the time of the Permian-Triassic extinction, an event destroying almost all animal life on Earth. Nor should we assume such events are flukes. Unlike the Moon (where there are at least 20 impact craters as large as this one), Earth’s meteor strikes tend to become obscured with time; even the Wilkes Land mascon will disappear because of geological activity in another half billion years.

These results were reported at the American Geophysical Union Joint Assembly meeting in Baltimore. And here’s Centauri Dreams‘ take: A better history of the battered early Earth will help us keep focused on planetary survival, and drive research into deep space exploration. For if we’re ever going to deflect an incoming asteroid or comet, we’ll need to do it as far out in the Solar System as possible where we have time and space to work with. In such ways do ancient craters have the potential for driving space research forward when more philosophical imperatives lose their punch.

Paul,

I just went to a set of talks recently in my department (Geology) relating to the P-T extinction event. They all sneered at the idea of an impact causing the extinction. Keep in mind, it wasn’t a geologist who came up with the idea of the K-T impact, it was a physicist, Luis Alvarez. Anyway, the main two reasons they were so derisive of an impact event was that 1) there was no crater, and 2) there was no diagnostic Iridium layer like we find with K-T. Well, potentially here is the P-T crater.

This could become a major area of new Antarctic research. So far, plate tectonics folks have completely avoided Antarctica, mainly because their methods including paleomagnetics, require direct access to rock. Since they can only get to rock in this part of Antarctica through coring, it will be interesting to see how this is compensated for.

That’s interesting! What can you tell us about paleomagnetics, and would such studies back up any potential iridium findings? I know nothing about how paleomagnetics works, so any thoughts you have would be helpful.