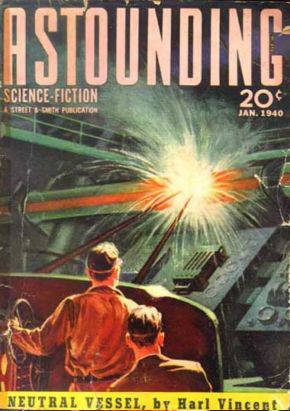

A recent acquisition has me looking backward rather than forward to begin the week. It’s the January 1940 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, a magazine then in its glory years under the editorship of John Campbell. Some of the authors here ring few bells: Sam Weston, for example, weighs in with “In the Day of the Cold,” as does D.L. James with “Moon of Delirium.” But this is also the issue of Robert Heinlein’s “Requiem,” and it contains good work by Lester del Rey and Edward E. Smith as well.

Astounding‘s science articles mixed with its ever reliable stories gave it a special place in the history of the pulp magazines, and many a scientist has told me that it was through Astounding or its later incarnation as Analog Science Fiction & Fact that a career path in physics or astronomy emerged. Which brought to mind science fiction writer Frederick Pohl, a distinguished editor in his own right.

Pohl’s 1978 memoir The Way the Future Was catches the magazine’s exciting heyday. He evokes the old building on Seventh Avenue where Astounding was produced, and recalls “…going up and down staircases, squeezing past rolls of paper stored to feed the ground-floor presses, reveling in the fascinating smells of printer’s ink and rotting wood.” In the passage that follows, Pohl recalls conversations with Campbell and their link to Astounding‘s editorials:

After a few such conversations, and after reading the editorials in Astounding a month or two after each of them, I figured out what was happening. That was how John Campbell wrote editorials. On the first of every month he would choose a polemical notion. For three weeks he would spring it on everyone who walked in. Arguments were dealt with, objections overcome, weak points shored up — and by the end of each month he had a mighty blast proof-tested against a dozen critics.

Every word he said I memorized:

On atmosphere: “I hate a story that begins with atmosphere. Get right into the story, never mind the atmosphere.”

On motivating writers: “The trouble with Bob Heinlein is that he doesn’t need to write. When I want a story from him, the first thing I have to do is think up something he would like to have, like a swimming pool. The second thing is to sell him on the idea of having it. The third thing is to convince him he should write a story to get the money to pay for it, instead of building it himself.”

On rejection letters: “When there’s something wrong with a story, I can tell you how to fix it. When it just doesn’t come across, there’s nothing I can say.”

On plot ideas: “When I think of a story idea, I give it to six different writers. It doesn’t matter if all six of them write it. They’ll all be different stories, anyway, and I’ll publish all six of them.”

On the archetypal sf story: “I want the kind of story that could be printed in a magazine of the year two thousand A.D. as a contemporary adventure story. No gee-whiz, just take the technology for granted.”

That latter item, of all Campbell’s dicta, seems to be the one most followed by modern science ficton, not always to its benefit since it can encourage a needless obscurity. Little of which you will find, it must be said, in today’s Analog, which continues to publish under the editorship of Stanley Schmidt, whose own tenure there is longer than any other editor save Campbell himself. Its science component is still robust, as witness the current issue’s discussion of current technology and interstellar possibilities by Gregory Matloff and Les Johnson.

And as to those old pulp issues like the one in the illustration above, they’re harder and harder to come by (most were destroyed in paper drives during World War II), but a small collector’s market still flourishes online in places like eBay, or at annual gatherings like PulpCon. Faced with a malfunctioning scanner, I poached the image above from the wonderful Pulps & Magazines Americains index of science fiction magazine covers and content. A few moments there, whether you read French or not, will trigger limitless nostalgia.

Good stuff!

The question I have is, when was the first starship written about in science fiction? And a follow on what was the first feasible (ok ok i’m sure that is a debatle point) startship? And of course the author.

For technical I keep coming to Dr. Forward with his star drive based on a laser that was stationed back in the Earth solar system. At certain times it shot it’s energy to a collector on the ship.

I know there are many earlier books, but I would have to select ‘ee. Doc Smith” for my first introduction to star ship.

Two extremely early entries would be C. L. Defontenay’s Star ou Psi de Cassiopée: Histoire Merveilleuse de l’un des Mondes de l’Espace (1854), which explored antigravity in its voyage to the planetary system Psi Cassiopeia, and Camille Flammarion’s Lumen (1872), a novel featuring a journey to Capella. I’d love to learn more about early interstellar treatments. The first fictional journey to Alpha Centauri that I know about is Wilhelm Mader’s 1911 novel Wunderwelten, translated into English in 1930 as Distant Worlds: The Story of a Voyage to the Planets. And an early Astounding story with a voyage to the Centauri system was Murray Leinster’s ‘Proxima Centauri.’

None of Campbell’s writers followed through the implications of “take the technology for granted” as skillfully as Heinlein, who pioneered a dozen ways to avoid the techno-info-dumps that had been so common earlier — and paid much more attention to how social behaviors and attitudes would be changed by technology.

I tuned in a decade post-pulp, already liking SF by age ten (1960), when my family moved to Manhattan. But it was the second-hand book and magazine shops there — where one week’s allowance could score a stack of 1950s Astoundings and Galaxies, plus some Groff Conklin paperback anthologies with the Good Stuff from the 1940s — that made it a true addiction.

Hi All

I had the fortune of being given a bunch of old “Astoundings” probably even the issue with the cover above. Some gems are a 1937 edition with an instalment of Doc Smith’s “Skylark of Valeron”, the issue with Leinster’s “A Logic Named Joe” (a 1946 prediction of the Internet), and Heinlein’s “Blowups Happen” in its 1940 edition – modern collections have the 1949 version of that story. The poor old pulps are flaking away and I’m not sure how to slow down their decay.

On starflight old Doc Smith began writing “The Skylark of Space” in 1915, before Gernsback published it in 1927 (?) But interstellar travel tales are older than that – Voltaire’s “Micromegas” is about a visit by a gigantic traveller from Sirius.

The first serious interstellar travel proposal was probably some idea dreamt up by Tsiolkovsky since he imagined so much else. Once sub-atomic energy was a physical possibility I think many thinkers and writers imagined interstellar flight. Most were ridiculously naive, usually ignoring Einstein, but John Campbell, for example, was a physicist and in his “The Mightiest Machine” he invoked a kind of hyperdrive to skirt around relativity.

From the 1940s total conversion drives were the usual sub-light concept invoked, especially by Heinlein. Fusion power began to be invoked in the later 1950s, and ramjets appeared after Bussard’s seminal paper in 1960. That idea dominated sub-light stories. In the early 1970s blackhole wormholes became popular as a relativistic lightspeed dodge, while antimatter rockets began appearing. Joe Haldeman invoked both in different tales, for example.

Laser-sails sprang forth in the early 1980s, thanks to Forward, but a whole range of concepts rattled around – amat rockets, ramjets, fusion rockets, vacuum energy ramjets (Sheffield and Clarke both used this one.) Greg Benford’s “Across the Sea of Stars” uses carbon-cycle fusion for its ramjet reactor. Plus all the vague and unphysical “drives” every SF writer has been tempted to invoke. Stable wormholes became HUGE in the late 1980s and early 90s, trailblazed by Sagan’s “Contact” and Kip Thorne’s work. Stephen Baxter’s GUT drive is another quite original drive from the early 1990s and in his recent novel “Exultant” he invokes a different Robert Forward drive, which used special oscillations of crystals to extract virtual photons from the vacuum, as well as a space-flaw concept.

Every new idea from theorists has propelled some story’s starship. Bob Forward’s negative matter drive is one favourite of mine, and his “Timemaster” put it to good use. Whether any of these ideas pans out is another matter entirely.

The most realistic, I think, are beamed mass or energy drives. “Mass beams” have been very well conceptualised in the “Epona” shared-world, and used to good effect in many other stories. Yet to be used in a major way is the related “sail-beam” concept developed by Jordin Kare. This is the most feasible in the short-term, as shown by an analysis by Andrews Aerospace’s Dana Andrews. Whether it inspires notable fiction is a good question: watch this space?

Adam

Adam, the best thing to help preserve those pulps is an archival sleeve that can at least slow down the decomposition. I get mine from Bags Unlimited (http://www.bagsunlimited.com/) and they’re available for all sizes of old magazines. Very useful!

I’m glad you brought up Campbell’s ‘Mightiest Machine.’ I had totally forgotten about it and will now go back and re-read it with new interest! I loved Forward’s Timemaster and I see that Kare keeps plugging at the sailbeam idea. No shortage of ideas when it comes to the interstellar conundrum.

Not all of the science fiction pulps disappeared during WWII, of course- I fondly remember Galaxy and Worlds of If (along with the briefly reincarnated Amazing Stories) before they too succumbed to harsh economics. The biggest problem with the pulps’ endangered status is the shrinking short story market for the next generation of science fiction writers. There are a few decent fanzines that publish fiction, but they have only a fraction of the circulation the pulps enjoyed, and in today’s dollars, pay even worse than the old “penny-a-word dreadfuls” that once proliferated on newsstands everywhere. Fanzines also tend to have a much shorter life cycle than the pulps of yesterday, making them elusive markets at best. Many a new writer cut their teeth on the pulps, which published far more duds than classics as writers learned their craft.

What George Burns once said about the death of Vaudeville is appropriate here: “There’s no place for the kids to be lousy anymore.”

The pulps were the Vaudeville for new writers, and the loss of all those skilled editors who were willing to work with no-name authors and whip bad stories into shape hurts not only science fiction, but writers in all genres.

The days of free (if sometimes harsh) mentoring while earning some encouraging pocket change are nearly gone now, and that’s really too bad.

The Burns comment is priceless, and so true.