New Horizons’ close approach to Jupiter on the 28th of February set up some intriguing observational possibilities. The Pluto-bound spacecraft now moves beyond the giant planet in a trajectory that takes it down Jupiter’s ‘magnetic tail,’ where sulfur and oxygen particles from its magnetosphere eventually dissipate. Since no spacecraft has ever been in this region before, coordinating what New Horizons sees with other instruments — both space-based and terrestrial — can tell us much about the Jovian environment.

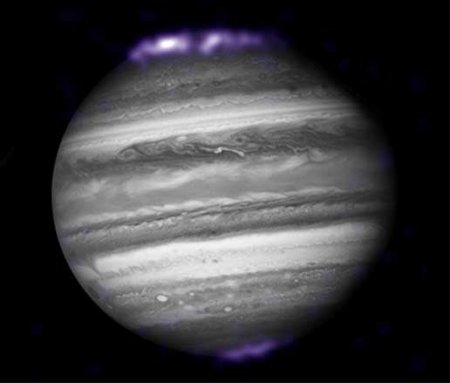

The image below is a composite of data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory superimposed upon the latest Hubble image. Notice the x-ray activity near the poles, where Chandra is detecting aurorae. The operative mechanism seems to be interaction between the solar wind and the sulfur and oxygen ions in Jupiter’s magnetic field, creating aurorae a thousand times more energetic than what we see on Earth.

Image: In preparation for New Horizon’s approach of Jupiter, Chandra took 5-hour exposures of Jupiter on February 8, 10, and 24th. In this new composite image, data from those separate Chandra’s observations were combined, and then superimposed on the latest image of Jupiter from the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SwRI/R.Gladstone et al.; Optical: NASA/ESA/Hubble Heritage (AURA/STScI).

To get a better picture of what’s going on, astronomers will tap observations by the Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE) satellite along with optical information from ground-based telescopes. How do the auroral emissions relate to what New Horizons will find as it moves down the magnetic tail? There will be no shortage of data as we marshall a wide range of resources to triangulate an answer. For New Horizons, Jupiter turns out to be much more than a simple gravity assist.

How intense would the X-rays be on the Galilean satellites, I wonder?

Andy, I wonder the same thing. Perhaps one of our resident astronomers can weigh in on that.

The New Horizons Pluto Kuiper belt Mission: An Overview with Historical Context

Authors: S. Alan Stern

(Submitted on 27 Sep 2007)

Abstract: NASA’s New Horizons (NH) Pluto-Kuiper belt (PKB) mission was launched on 19 January 2006 on a Jupiter Gravity Assist (JGA) trajectory toward the Pluto system for a 14 July 2015 closest approach; Jupiter closest approach occurred on 28 February 2007. It was competitively selected by NASA for development on 29 November 2001.

New Horizons is the first mission to the Pluto system and the Kuiper belt; and will complete the reconnaissance of the classical planets. The ~400 kg spacecraft carries seven scientific instruments, including imagers, spectrometers, radio science, a plasma and particles suite, and a dust counter built by university students. NH will study the Pluto system over a 5-month period beginning in early 2015. Following Pluto, NH will go on to reconnoiter one or two 30-50 kilometer diameter Kuiper belt Objects (KBOs), if NASA approves an extended mission.

If successful, NH will represent a watershed development in the scientific exploration of a new class of bodies in the solar system – dwarf planets, of worlds with exotic volatiles on their surfaces, of rapidly (possibly hydrodynamically) escaping atmospheres, and of giant impact derived satellite systems. It will also provide the first dust density measurements beyond 18 AU, cratering records that shed light on both the ancient and present-day KB impactor population down to tens of meters, and a key comparator to the puzzlingly active, former dwarf planet (now satellite of Neptune) called Triton, which is as large as Eris and Pluto.

Comments: 18 pages, 4 figures, 2 tables; To appear in a special volume of Space Science Reviews on the New Horizons mission

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0709.4417v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Harold Weaver Jr [view email]

[v1] Thu, 27 Sep 2007 15:03:39 GMT (1760kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0709.4417

The New Horizons Spacecraft

Authors: Glen H. Fountain, David Y. Kusnierkiewicz, Christopher B. Hersman, Timothy S. Herder, Thomas B. Coughlin, William C. Gibson, Deborah A. Clancy, Christopher C. DeBoy, T. Adrian Hill, James D. Kinnison, Douglas S. Mehoke, Geffrey K. Ottman, Gabe D. Rogers, S. Alan Stern, James M. Stratton, Steven R. Vernon, Stephen P. Williams

(Submitted on 26 Sep 2007)

Abstract: The New Horizons spacecraft was launched on 19 January 2006. The spacecraft was designed to provide a platform for seven instruments that will collect and return data from Pluto in 2015. The design drew on heritage from previous missions developed at The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) and other missions such as Ulysses. The trajectory design imposed constraints on mass and structural strength to meet the high launch acceleration needed to reach the Pluto system prior to the year 2020. The spacecraft subsystems were designed to meet tight mass and power allocations, yet provide the necessary control and data handling finesse to support data collection and return when the one-way light time during the Pluto flyby is 4.5 hours. Missions to the outer solar system require a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) to supply electrical power, and a single RTG is used by New Horizons. To accommodate this constraint, the spacecraft electronics were designed to operate on less than 200 W. The spacecraft system architecture provides sufficient redundancy to provide a probability of mission success of greater than 0.85, even with a mission duration of over 10 years. The spacecraft is now on its way to Pluto, with an arrival date of 14 July 2015. Initial inflight tests have verified that the spacecraft will meet the design requirements.

Comments: 33 pages, 13 figures, 4 tables; To appear in a special volume of Space Science Reviews on the New Horizons mission

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0709.4288v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Harold Weaver Jr [view email]

[v1] Wed, 26 Sep 2007 23:46:03 GMT (2887kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0709.4288

New Horizons: Anticipated Scientific Investigations at the Pluto System

Authors: Leslie A. Young, S. Alan Stern, Harold A. Weaver, Fran Bagenal, Richard P. Binzel, Bonnie Buratti, Andrew F. Cheng, Dale Cruikshank, G. Randall Gladstone, William M. Grundy, David P. Hinson, Mihaly Horanyi, Donald E. Jennings, Ivan R. Linscott, David J. McComas, William B. McKinnon, Ralph McNutt, Jeffery M. Moore, Scott Murchie, Carolyn C. Porco, Harold Reitsema, Dennis C. Reuter, John R. Spencer, David C. Slater, Darrell Strobel, Michael E. Summers, G. Leonard Tyler

(Submitted on 26 Sep 2007)

Abstract: The New Horizons spacecraft will achieve a wide range of measurement objectives at the Pluto system, including color and panchromatic maps, 1.25-2.50 micron spectral images for studying surface compositions, and measurements of Pluto’s atmosphere (temperatures, composition, hazes, and the escape rate). Additional measurement objectives include topography, surface temperatures, and the solar wind interaction. The fulfillment of these measurement objectives will broaden our understanding of the Pluto system, such as the origin of the Pluto system, the processes operating on the surface, the volatile transport cycle, and the energetics and chemistry of the atmosphere. The mission, payload, and strawman observing sequences have been designed to acheive the NASA-specified measurement objectives and maximize the science return. The planned observations at the Pluto system will extend our knowledge of other objects formed by giant impact (such as the Earth-moon), other objects formed in the outer solar system (such as comets and other icy dwarf planets), other bodies with surfaces in vapor-pressure equilibrium (such as Triton and Mars), and other bodies with N2:CH4 atmospheres (such as Titan, Triton, and the early Earth).

Comments: 40 pages, 9 figures, 7 tables; To appear in a special volume of Space Science Reviews on the New Horizons mission

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0709.4270v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Harold Weaver Jr [view email]

[v1] Wed, 26 Sep 2007 21:40:28 GMT (1249kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0709.4270

Overview of the New Horizons Science Payload

Authors: H. A. Weaver, W. C. Gibson, M. B. Tapley, L. A. Young, S. A. Stern

(Submitted on 26 Sep 2007)

Abstract: The New Horizons mission was launched on 2006 January 19, and the spacecraft is heading for a flyby encounter with the Pluto system in the summer of 2015. The challenges associated with sending a spacecraft to Pluto in less than 10 years and performing an ambitious suite of scientific investigations at such large heliocentric distances (greater than 32 AU) are formidable and required the development of lightweight, low power, and highly sensitive instruments. This paper provides an overview of the New Horizons science payload, which is comprised of seven instruments. Alice provides spatially resolved ultraviolet spectroscopy. The Ralph instrument has two components: the Multicolor Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC), which performs panchromatic and color imaging, and the Linear Etalon Imaging Spectral Array (LEISA), which provides near-infrared spectroscopic mapping capabilities. The Radio Experiment (REX) is a component of the New Horizons telecommunications system that provides both occultation and radiometry capabilities. The Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) provides high sensitivity, high spatial resolution optical imaging capabilities. The Solar Wind at Pluto (SWAP) instrument measures the density and speed of solar wind particles. The Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation (PEPSSI) measures energetic protons and CNO ions. The Venetia Burney Student Dust Counter (VB-SDC) is used to record dust particle impacts during the cruise phases of the mission.

Comments: 17 pages, 4 figures, 1 table; To appear in a special volume of Space Science Reviews on the New Horizons mission

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0709.4261v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Harold Weaver Jr [view email]

[v1] Wed, 26 Sep 2007 20:48:59 GMT (1143kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0709.4261

The ion-induced charge-exchange X-ray emission of the Jovian Auroras: Magnetospheric or solar wind origin?

Authors: Yawei Hui, David R. Schultz, Vasili A. Kharchenko, Phillip C. Stancil, Thomas E. Cravens, Carey M. Lisse, Alexander Dalgarno

(Submitted on 9 Jul 2009)

Abstract: A new and more comprehensive model of charge-exchange induced X-ray emission, due to ions precipitating into the Jovian atmosphere near the poles, has been used to analyze spectral observations made by the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

The model includes for the first time carbon ions, in addition to the oxygen and sulfur ions previously considered, in order to account for possible ion origins from both the solar wind and the Jovian magnetosphere.

By comparing the model spectra with newly reprocessed Chandra observations, we conclude that carbon ion emission provides a negligible contribution, suggesting that solar wind ions are not responsible for the observed polar X-rays. In addition, results of the model fits to observations support the previously estimated seeding kinetic energies of the precipitating ions (~0.7-2 MeV/u), but infer a different relative sulfur to oxygen abundance ratio for these Chandra observations.

Comments: 11 pages, 2 figures, 2 tables, submitted to ApJ Letter

Subjects: High Energy Astrophysical Phenomena (astro-ph.HE); Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:0907.1672v1 [astro-ph.HE]

Submission history

From: Yawei Hui [view email]

[v1] Thu, 9 Jul 2009 20:36:39 GMT (151kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0907.1672