With our eyes on a proposed interstellar future, we don’t want to neglect the real challenges of preserving the steps taken along the way. I’m thinking about this because of a post on an astronomy list (thanks to Larry Klaes for the pointer) by Richard Sanderson, who is curator of physical science at the Springfield Science Museum (MA). Sanderson is worried about the media upon which we store our information, and for good reason. Here’s the issue in a nutshell:

The difficulties that future historians may encounter are related to the ephemeral nature of digital information and the media used to store it. I can visit an old monastery in Europe, find a giant leather-bound astronomy book from the 17th century, blow off the dust, open it, and read the pages (provided I can read Latin). The only tools required are my eyes and hands. But imagine someone living in the 23rd or 24th century who finds an old box of computer diskettes or CDs. Even if the diskettes haven’t been corrupted and the CDs haven’t delaminated, will that person be able to access the information?

The question surfaces enough in the computer press to give at least some reassurance that it’s under active study, and of course we have projects like the Internet Archive at work, attempting to preserve such ephemera as short-lived Web sites, particularly those associated with concrete events that have their brief moment in the Sun and then disappear. Sanderson quotes Curator, a magazine for museum professionals, to the effect that while high-quality photographic film can last 500 years, unmanaged digital media have a life expectancy of only five. We have examples of books in our museums that have lasted for centuries, but in the digital age we’re constantly forced to transfer our data from one medium to another.

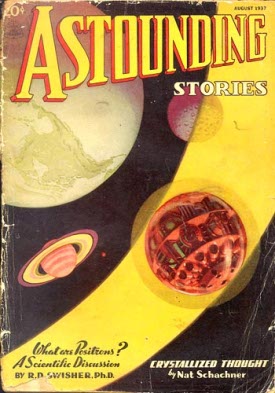

I can see signs of the problem in my own life. I’m using old pulp magazines, some of them collected forty years ago, some recently bought, to work on a book project. An Astounding Story: Science & Fiction in the Golden Age looks at the changing views of science presented by these magazines in the first third of the 20th Century. Anyone who has collected pulps knows that severe limitations are in play here. Not only did World War II paper drives lead to the destruction of vast stores of the magazines, but the paper they were printed on was high in acid, making their deterioration a process that is all but impossible to reverse.

Image: The August, 1937 issue of Astounding Stories. Finding old issues of popular magazines is complicated by the fact that most people in their time saw no need to preserve them.

So I use the lovely old volumes with caution, otherwise keeping them stored in transparent envelopes made for the purpose. It’s remarkable to me how few of these magazines, which reflect their time and place so well, have been digitized against the day when they’re all but unusable. Simple OCR isn’t adequate, because we need the context as well as the content. We need to see the surrounding material, the ads, the illustrations, the environment of the text that informs how people in that era experienced the embedded stories and occasional science article.

Shifting media a bit, I’m also an inveterate collector of old movies. I have some 1400 films going back to the silent era and ending in the mid-1950s (1956, the year Bogart died, is usually my terminus). All of these have been taped from movie channels and now reside on VCR tapes, yet another example of a technology whose day is passing. I could re-master these onto DVD but the task is enormous. In any case, a DVD recorder would allow me to reassemble many of them at far higher quality as presented on my new HDTV. How to proceed, and when to switch?

Sanderson calls this the ‘stewardship’ problem:

Unlike books and paper archives, which only require a decent environment and some security, digital media require continual stewardship, which translates into a significant investment of time and money. As time goes on, data must be transferred over and over onto newer media so that both the information and the context (software) are preserved and made accessible using future digital equipment. The stewardship problem is exacerbated by the sheer volume of digital data being generated.

So are we entering a ‘dark age’ of science that passes along to the future a record containing large holes where digital data were mismanaged? Let’s hope not, but we have to be aware of the danger. Years ago in Reykjavik, as a UNC graduate student trying to master Old Icelandic, I examined a manuscript called the Flateyjarbók at the Háskóli Íslands (University of Iceland). The manuscript, 225 vellum leaves containing sagas of the Norse kings, historical annals and poetry, has survived since the late 14th Century and remains an exquisite testament to a people and their times. Knowing its fragility and its age, not to mention the uniqueness of its contents, we have no doubt that it needs to be preserved.

Image: A page from the Norse saga of King Sverre Sigurðsson in the Flateyjarbók, a manuscript that has endured for centuries, challenging us to find better ways to preserve data that may otherwise be lost. Credit: Árni Magnússon Institut, Reykjavik.

The trick is in understanding things that are closer to our own time. Materials that seem pedestrian to us can quickly disappear. In an era where so many journals are expanding their online presence, where peer review is being taken into new and productive realms on the Internet and the very idea of the book is being challenged by digital devices, we need to remember that science builds upon the efforts of those who have come before. As we take the first tentative steps toward an interstellar culture, we are in a transitional period in data stewardship that is fraught with peril. Let’s be careful about preserving that future history.

I just saw a picture of a few volumes of R. Buckminster Fuller’s “Chronofile,” a collection of his sketches, letters, newspaper clippings, and other things. Despite its sleek-sounding name, all these are collected in thick, bound volumes—in other words, books. I was surpised that Fuller, so concerned with making structures as ephemeral as possible, would choose such a heavy, old-fashioned looking method for storing the collected data of his life. After reading this, I’m thinking it’s just another example of his foresight.

The information loss problem that you describe has resulted in the loss of tens, and perhaps hundreds, of millions of dollars worth of geophysical data. Throughout most of the 1960’s, 70’s, and 80’s, geophysical processing contractors made little or no attempt to competently archive millions of miles of airborn geomagnetic, electromagnetic, and radiometric data collected over vast areas of our planet. Most of this data has now been permenantly lost due to deteriation of the old tape storage media. Even if the data were still available in the original format it would be largely irretreavable because the information specifying the recording formats, and the processing systems required, have both been lost.

NASA has a similar problem. Years of data from early satellites were recorded on now obsolete analog equipment. Worse, many of those priceless tapes have deteriorated due to poor archival storage practices to the point that even if the equipment could be found or fabricated to retrieve that data, thousands of hours is beyond salvage. NASA dropped the ball when it came to judiciously preserving some of its early findings, much to the detriment of Earth and space scientists today who could have found that data an invaluable touchstone for modern experiments measuring the same factors.

Reading the “Foundation” stories in technological retrospect I always smile at their use of “microfilm”, but perhaps simplistic optical media are a good way to go for very long term storage? At least the retrieval process doesn’t necessarily involve arcane electronic protocols. Isn’t there a group making a “Rosetta Stone” for future ages?

On the other hand, Hal Clement has a space crew using slide rules in Mission of Gravity… Though not, obviously, for data storage.

Re Rosetta, yes indeed. The Rosetta Project is here:

http://www.rosettaproject.org/

Read another real life story about the Pioneer anomaly data, where a lot of problems showed up, such as to find a DEC computer which still runs and has the necessary software to read the old data. Which, of course, are in a format actually known only to a handful engineers left…

Here is the link to Lou Friedman`s Emergency Letter on The Planetary Society pages:

http://www.planetary.org/programs/projects/innovative_technologies/pioneer_anomaly/20070831.html

Hi Paul,

Any chance for a link to the article by Sanderson ?

Many thanks,

Mark

Actually, quite a few vintage computer collectors can be put to work to retrieve data stored on old media. There are DEC system collectors who have working 9-track tape drives and the programming skills to interpret and convert the data for export to modern systems. In my personal collection I have a Compupro S-100 micro system with 8″ floppy disk drives and several brand-new spares! Perhaps not very useful for the task in your article (most data was probably stored on magnetic tape), but it goes to show that much of the old hardware exists in operational condition. It would give collectors something useful to do with their beautiful old hardware!

Mark, re the link to the Sanderson article, good idea. Let me see if I can track the link down — right now I’ve only got the straight text, and I haven’t found a link outside the mailing list archive, which requires a password login.

jr_brady, what a wonderful notion about resurrecting old hardware!

Thanks! When I started collecting vintage computers I was amazed at the size of the community and passion of my fellow collectors. At one point I had over a dozen working systems with spare parts, software, documentation and peripherals. I even owned a working VAX-11/750, since donated to the Computer History Museum in California. I met people with garages full of working PDPs, IBM mainframes, micros, you name it. I bet most of them are still around and would participate in a data recovery/archival project if the opportunity arose. Later the torch could be passed to the next generation after today’s media becomes equally obsolete.

I just wanted to say that I want a copy of An Astounding Story as soon as it hits the bookshelves.

–Danny, who owns a collection of 1930’s and WWII-era pulp SF magazines himself while simultaneously being almost afraid to touch them

Perhaps, borrowing from Ike Asimov again, there really should be a Foundation to preserve old knowledge? We have the means surely to do archiving unlike any other age before us.

Consider the human genome – 6.3 billion nucleotides sense/anti-sense. Using the usual symbols, AGTC, that means a book of 630,000 pages with 10,000 symbols per page – virtually a library. Store a few versions, all known alleles, and that quantity balloons. Then do it for all known genomes. But electronically this is not an onerous task and, with sufficient skill, not exceptionally hard to track down homologous sequences in either via automated programs. Surely we can breakdown all the old storage skills into very simple-to-follow algorithms for all future ages to come.

The problem is will – and there seems to be abundant will out in the wider community.

Danny, we share a common problem! Opening up some of the older magazines can be a scary proposition — I find myself approaching them sometimes as museum pieces, afraid to do damage to page and spine. What I wouldn’t give for a well digitized collection of all the early issues… One day, I suppose, we’ll have materials like this and all the pre-digital printed materials well scanned, both via OCR and straight image, but that day seems a long way off.

Adam writes:

I suppose the Long Now Foundation is the closest we have to this in terms of an explicit foundation, although theoretically, of course, universities have this built into their charter (I leave aside for a moment whether or not most are living up to it!). The genome idea is fascinating and I share your optimism about their being an abundance of will out there waiting to take on these tasks. I’m sure they’ll get done, but we should probably keep poking and prodding to make sure the issue stays in focus.

The Future of the Past, an absorbing book by Alexander Stille, addresses the issues of conservation and preservation — of books, archeological findings, esoteric skills… It contains at least one glaring error: it names “St. Cyrus” as the originator of the Cyrillic script instead of Cyrillus and Methodius. But it covers very interesting territory, including the increasing fragility and fungibility of reading/writing media.

Several years ago Robert Shapiro proposed the Alliance to Rescue Civilization (ARC) project, “…a group that advocates a backup for humanity by way of a station on the Moon replete with DNA samples of all life on Earth, as well as a compendium of all human knowledge..”

I do not know the status of the proposal, but this is the link on the Lifeboat Foundation site to Shapiro`s bio:

http://lifeboat.com/ex/bios.robert.shapiro

Anybody out there with fresh knowledge about this proposal?

Tibor

A further complication was the fact that most ancient information survived by chance rather than design. If those Medieval monks had not re-used all those old manuscripts…

Any preservation scheme needs LOTS of copies. An expensive, high tech single site repository is not going to work.

My day job has a long title; I’m the Manager of the Regional Planetary Information Facility in the Astrogeology Team at the U.S. Geological Survey Flagstaff Science Center. Basically, I’m a glorified dumpster diver. I pull together Astro’s scattered documentation of past space missions and repackage it to preserve it and enhance access to it. We have, for example, all of Mariner 9’s Mars images in hardcopy format, and extensive correspondence documenting the Apollo landing site selection process.

Digital formats are convenient in the short-term, but if one really values what one is doing and wishes to make it available to the next generation so that they can make of it what they will, one needs to keep hardcopy. Digitial formats are not a replacement for hardcopy, though that’s the way they are perceived. They are a presentation method.

In Astro, history more or less ends in the 1990s because that’s when the team started to conduct all of its business digitally. Astro is not unique in this. I think of that as the start of the dark age. Already, digital data generated during that period is becoming inaccessible, and it has no hardcopy backup. Of course, as others have pointed out, the problem began earlier.

I resist placing all of our collections online because it might lead some unenlightened bureaucrat at some point to say, “all of this hardcopy is redundant, so let’s create some new office space by ridding ourselves of it.” Of course it’s redundant – that’s the whole point.

It’s as if we’re burning our libraries to power the digital age.

I’m looking forward to reading the book Athena recommended, Stille’s The Future of the Past, to put these matters further into context.

And David, re your comment on burning our libraries, I think similar thoughts whenever I get into the local community library system. Every year fewer books are actually on the shelves, while computer equipment takes over more and more space…

Re the above for background,and it will date my humble self,

‘A Canticle for Leibowitz” Walter Miller,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Canticle_for_Leibowitz

and of course Neal Stephesnson’s new tome,

‘Anathem’ a novel of some interest to the topic. Long Now website etc…

Mark

Good discussions here.

Issues of long term communication, accidental or not, I treated somewhat in my DEEP TIME (1999).

Interestingly enough I just posted the Clayton Astoundings to the Internet Archive. Do a book search for “Astounding Stories” The issues after that aren’t going to be posted.

Well done, Greg! I can’t wait to go through this material. For those interested, go to:

http://www.archive.org

and run a search for ‘astounding stories’. Excellent resource!

Maybe we can broadcast all those books into space and then wait for aliens to come back and return them to us?

Mike

July 10, 2009

Stephanie Schierholz

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-4997

stephanie.schierholz@nasa.gov

RELEASE: 09-158

NASA TO PROVIDE EDUCATION FUNDING FOR MUSEUMS AND PLANETARIUMS

WASHINGTON — NASA has announced a competitive funding opportunity for

informal education that could result in the award of grants or

cooperative agreements to several of the nation’s science centers,

museums and planetariums. Approximately $6 million is available for

new awards.

Proposals for the Competitive Program for Science Museums and

Planetariums are expected to use NASA resources to enhance informal

education programs related to space exploration, aeronautics, space

science, Earth science or microgravity. Full proposals are due Sept.

10.

NASA is uniquely positioned to contribute to informal education

through its remarkable facilities, missions, data, images, and

employees, including internationally-known engineers and scientists.

Proposals for the program are expected to encourage life-long

engagement in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, and

focus on NASA’s contributions to these disciplines. NASA already

provides interested science centers, museums and planetariums access

to informal education resources — NASA images, visualizations,

video, and information — free of charge through NASA’s Museum

Alliance.

NASA will accept proposals from institutions of informal education

that are science museums or planetariums in the United States or its

territories. NASA centers, federal agencies, federally funded

research and development centers, education-related companies, and

other institutions and individuals may apply through partnership with

a qualifying lead organization.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., which leads the

Museum Alliance, will conduct an external peer review process for the

proposals. Authority for final award selections rests with the Office

of Education at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

Informal education is recognized as a successful tool for learners of

all ages. Recently, the National Academy of Sciences published a

study, “Learning Science in Informal Settings: People, Places,

Pursuits,” which found evidence that informal education programs

involving exhibits, new media and hands-on experiences — such as

public participation in research — increase interest in science,

technology, engineering, mathematics and related careers for both

children and adults.

Congress initiated the Competitive Program for Science Museums and

Planetariums in 2008 to enhance programs related to space

exploration, aeronautics, space science, Earth science or

microgravity. On June 3, NASA selected 13 organizations for the first

group of projects.

For detailed information about the funding opportunity, click on “Open

Solicitations” and look for Competitive Program for Science Museums

and Planetariums (CP4SMP) or solicitation number NNH09ZNE005N at:

http://nspires.nasaprs.com

This funding opportunity supports NASA’s education goal to engage

students in science, technology, engineering and mathematics related

to NASA missions and careers. For more information about NASA’s

education programs, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/education

For more information about the Museum Alliance and to join, visit:

http://informal.jpl.nasa.gov/museum