1951’s The Man from Planet X is a creepy Edgar G. Ulmer film involving an inscrutable alien whose small craft falls to earth in the moors of Scotland. There he is attacked, exploited and ends up being killed in spite of the fact that his real mission was apparently peaceable. The film is noir-like, the sets foggy and surreal, and although the dialog positively creaks, the moody atmosphere still puts a chill up my spine.

I mention this personal favorite because my copy of The Man from Planet X has a glitch, a defect in the aging tape that causes the image to jitter for a ten second period just as actress Margaret Field is getting progressively spooked by the strange alien craft. You would think that an upgrade to DVD is in order, and indeed, that’s my only real choice. But the other night, watching a DVD of Alec Guinness in the delightful Our Man in Havana (1959), I saw the image lock up and freeze, decomposing into pixels that reconfigured themselves only after a couple of minutes had passed. This, mind you, was on a relatively new DVD.

The Pleasures of an Older Medium

There are times when the older medium, VCR tape, is actually preferable in one sense — it recovers better from the kind of errors that can lock up a DVD. I think about these things because my obsession with the past and the recovery of seemingly lost history is very much involved with technology. Consider how image processing is now used to restore what was written on an ancient papyrus, or the way the Beowulf manuscript has been enhanced and re-examined through various electronic filters to tease out new information. See The Electronic Beowulf for more.

We are now able to extract information from palimpsests — vellum manuscripts once scraped and used again for new material written over the old — by imaging what was written in the earlier layer. Parchment was scarce in the Middle Ages, which is why a manuscript might be scraped with powdered pumice. The seemingly destructive practice yields at least some of its secrets to so-called multispectral filming, which recently recovered four-fifths of a priceless text by Archimedes. Various forms of x-ray imaging are also in play.

Lunar Images Back from the Dead

But back to space. The Lunar Orbiter Image Recovery Project shows us how heedless we’ve been in our rush to digitize. Located at NASA Ames, LOIRP had to acquire one of the last surviving Ampex FR-900 machines to play back analog data from our early Moon probes, information now being digitized to tease out new science. I think about that when I look at tape cassettes I recorded thirty years ago. I need a tape deck to play them and wonder how long cassette options, still built into many multimedia centers, will be available. Think of 8-track players.

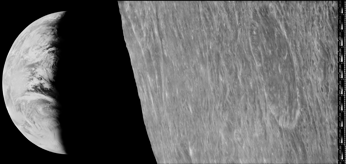

Image: Restored Lunar Orbiter view of Earthrise over the Moon. The FR-900 tape drives that held this and other images sat in a Sun Valley, CA barn for several decades before this restoration was made.

If you have a collection of old data, as I do on my hundreds of old movies recorded over two decades, you’re faced with the need to move to new formats to keep it viable. Here again the oddity: We have written manuscripts that are readable from the last two millennia, physical objects whose one great characteristic is the preservation of the content they carry. The photos we stuffed in our living room drawers are still there, but how long will the online service that hosts our new digital snaps stay healthy enough to host them?

David Pogue recently talked to Dag Spicer, curator of the Computer History Museum in Silicon Valley, about the issue. Spicer had this to say:

One of the technologies for really long-term preservation was developed at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. It was, I think, a titanium disk about the size of a long-playing record, and it was supposed to last 10,000 years. But then they realized that there were some assumptions that weren’t right, and that it would not last 1,000 years, it might only last 20.

Otherwise, as far as I know, no one is working on this problem. It’s really in no one’s interest, no manufacturer’s interest; they want to keep selling you more hard drives every two to five years, or more blank CDs, and what have you.

Recovering Old Machines, Building Better Ones

Much of our early space data exists under the same cloud. We need specialized machines to read the information, and the machines are increasingly scarce. We’re in the data gap between analog and digital, a place in which a few fumbles can make key aspects of who we were in the 20th Century unrecoverable. Meanwhile, the Long Now Foundation keeps pushing the value of planning for the long term, a set of values that should eventually help us create data formats and methods that don’t, like too many old films, let our images and stories gradually deteriorate inside cannisters nobody ever opens.

We’ll get there, of course, but the experience should serve as an object lesson in how to place change in context. We are pushing inexorably toward a future that, some of us believe, involves movement into the outer Solar System and beyond. We are taking data at unprecedented rates through a wide variety of experiments and observations. The challenge will be to preserve what we have while going forward, a task that should be hard-wired into the design of future technology.

Paul;

This post reminds me of our prior discussions about occassionally compiling and book-publishing the contents of our websites – Centuari Dreams and Tau Zero – for archival sake and to make such things assessible via another venue.

Books do seem to have a degree of logevity that even the Long Now Foundation appreaciates. And it is with that thought that I have a twinge of contentment from having just finished “Frontiers of Propulsion Science” (AIAA 2009).

Marc Millis writes:

I still think about this, Marc, particularly given how many new publishing options have opened up in the past decade or so. Centauri Dreams is now up to about 1500 posts, so if we go that route, we’d better break that into a couple of separate volumes or it’s going to be even bigger than Frontiers of Propulsion Science! About which, what a pleasure to hear that our mutual friend Tibor Pacher was showing the book to participants at the recent Charterhouse interstellar session.

I just wanted to let you know how much I have enjoyed Centauri Dreams over the years! What a wonderful information filled blog! I so hope that humanity can conquer its problems and head to the stars. I do not think I will see the first relativistic starship heading off to a stellar neighbor in my lifetime-but I would like to think that historically speaking this time isn’t far off down the road. In the meantime it astonishes me -the things we are able to learn! If the cooler stars of the stellar population can support life-there is no telling how many different lifeforms there are in the universe. I agree about the rush to digitize all of this data-thanks for bringing this up. Best to you and thanks again for your wonderful blog!

Very kind words, Devin, and thanks. I deeply appreciate this readership and hope we’ll have all of you around here for a long time!

To some extent, ‘The Cloud’ may have some impact here. When all your information is stored on a ‘cloud’ or ‘grid’ of servers with redundancy built-in, then you are no longer reliant upon individual pieces of hardware, or indeed individual types of technology. As spinning drives give way to flash drives, then whatever comes next, the data is automatically replicated on to the new medium. The cloud doesn’t care *where* the data is.

However, this of course only solves part of the problem. It doesn’t tackle the preservation of data that is too private to risk storing on the cloud. And it doesn’t necessarily handle the problem of obsolete file formats.

The latter problem at least does appear to be taken seriously these days. I think what’s happened is that we’ve reached the point where computers have been around in offices and homes for long enough that many people have been bitten by the problem of not being able to open old files because the new application doesn’t support them. We are seeing a lot more use of formats that are based on XML, for example (which although ugly to read is at least readable; well, in theory :-) ),

Pat Galea writes:

Excellent point! I thought about the cloud concept when I was writing the piece, because massively redundant backup on servers located around the globe are a solution to the hardware problem, at least in terms of upgrading home and office equipment so frequently. That obsolete file format problem does continue to haunt us, as I am reminded when I look back at all the columns, essays and articles I wrote using the old XYWrite program. Earlier versions produced readable enough ASCII, but the later versions started coming up with proprietary solutions that need the original software to read. And then there are all the pieces I wrote using WordPerfect in various incarnations… Drives me crazy sometimes.

I’ve heard there are similar problems with government records generally. Up through the 1950s almost all records were on paper, but beginning in the 1960s electronic recording started to be used more often. Many of these electronic records are in media and formats for which equipment is no longer made.

NS, thanks for that point. That ‘window’ between about 1960 and 1985 seems particularly vulnerable when it comes to record-keeping of all types and our ability to read it today. It’s heartening to see the problem coming under wider discussions in places like David Pogue’s essay. And in our field of work, the Pioneer anomaly has brought it into focus, since the older Pioneer date was initially saved on equipment that now has to be reconstructed.

Marc, Paul,

– this is a great idea! I would be happy to hold such a book – better, books – in my hands. What do you think about a sort of “Best of Centauri Dreams ” Volume? – this could (a must then, to me!) be translated into several languages, imho.

Happy Easter to all Centauri Dreams readers – accompanied with a great thank you to Paul for this wonderful venue!

Tibor

Frontiers of Propulsion Science is indeed an excellent book. I’m partway through it, but I have skimmed the rest of the book and I believe it’ll become a classic in the field, and required reading for anyone starting out.

I was at the Charterhouse interstellar session too (I was the guy in the front row near the door asking lots of awkward questions! :-) ). Every talk at the session was fascinating, and after a good chat with Claudio Maccone after his talk, I ordered his new book.

Pat, I haven’t seen Claudio’s new one yet, but am certainly looking forward to it. His contributions to the field are immense and growing. Thanks for the kind words re Frontiers of Propulsion Science, thoughts which editors Marc Millis and Eric Davis will both see here. They deserve the praise!

Tibor writes:

All ideas welcome, though I suspect the next big push is going to be in developing the follow-up volume to Frontiers of Propulsion Science, aimed at the non-specialist. But I do like the idea of eventually compiling the Centauri Dreams material. Will keep you posted, Tibor!

My copy of Maccone’s book arrived today. :-)

Building a stellar time machine

July 7, 2009 by Alvin Powell

Jonathan Grindlay (from left), Paine Professor of Practical Astronomy, Alison Doane, curator of plate stacks, Edward Los, software engineer, and Sumin Tang, research assistant in astronomy, are part of the DASCH project, which aims to digitize 525,000 glass photographic plates taken in the last century.

Photograph here:

http://www.physorg.com/news166197904.html

(PhysOrg.com) — Harvard researchers are building a celestial time machine that lets astronomers look back at hundreds of thousands of objects in Earth’s skies over the past century.

The effort aims to digitize 525,000 glass photographic plates taken at observing sites around the world between the 1880s and the 1980s. The collection, the largest such in the world, contains a treasure trove of largely unexamined data, according to Paine Professor of Practical Astronomy Jonathan Grindlay, who is leading the digitizing effort.

Grindlay said each of the plates has been examined for one or a few objects of interest to specific astronomers. When one considers that each plate holds images of upwards of 100,000 objects and that each visible object has been photographed between 50 and 3,000 times over the years, the potential knowledge about the changing universe hidden in the Harvard College Observatory plate stacks is enormous.

“DASCH will look at every object on the plate with specially developed software and measure its brightness. You can not know what you’re looking for and still find something,” Grindlay said. “We’re part of a wave that is looking at the sky for its variable objects, for everything that goes bump in the night — and that turns out to be a lot. DASCH will open a new window for time domain astronomy.”

Full article here:

http://www.physorg.com/news166197904.html

The Web site for DASCH is here:

http://hea-www.harvard.edu/DASCH/

More on the Harvard DASCH project at this site:

http://hea-www.harvard.edu/DASCH/index.php

And an earlier work on digitizing the Harvard plates here:

http://tdc-www.harvard.edu/plates/

Astroinformatics: A 21st Century Approach to Astronomy

Authors: Kirk D. Borne (1) ((1) George Mason University)

(Submitted on 22 Sep 2009)

Abstract: Data volumes from multiple sky surveys have grown from gigabytes into terabytes during the past decade, and will grow from terabytes into tens (or hundreds) of petabytes in the next decade. This exponential growth of new data both enables and challenges effective astronomical research, requiring new approaches.

Thus far, astronomy has tended to address these challenges in an informal and ad hoc manner, with the necessary special expertise being assigned to e-Science or survey science. However, we see an even wider scope and therefore promote a broader vision of this data-driven revolution in astronomical research.

For astronomy to effectively cope with and reap the maximum scientific return from existing and future large sky surveys, facilities, and data-producing projects, we need our own information science specialists.

We therefore recommend the formal creation, recognition, and support of a major new discipline, which we call Astroinformatics. Astroinformatics includes a set of naturally-related specialties including data organization, data description, astronomical classification taxonomies, astronomical concept ontologies, data mining, machine learning, visualization, and astrostatistics.

By virtue of its new stature, we propose that astronomy now needs to integrate Astroinformatics as a formal sub-discipline within agency funding plans, university departments, research programs, graduate training, and undergraduate education.

Now is the time for the recognition of Astroinformatics as an essential methodology of astronomical research. The future of astronomy depends on it.

Comments: 14 pages total: 1 cover page, 3 pages of co-signers, plus 10 pages, Astro2010 Decadal Survey State of the Profession Position Paper

Subjects: Instrumentation and Methods for Astrophysics (astro-ph.IM)

Cite as: arXiv:0909.3892v1 [astro-ph.IM]

Submission history

From: Kirk D. Borne [view email]

[v1] Tue, 22 Sep 2009 02:21:49 GMT (449kb,X)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0909.3892

“Rescuing our photographic heritage”

Group moves to safeguard and archive astronomical plates.

by

Martin Ratcliffe

April 22nd, 2005

Astronomy

There are more than three million slowly deteriorating photographic plates recorded over a century and a half at many small observatories around the world. With today’s digital revolution in full swing, it would be easy to forget the huge wealth of data recorded by early observers using photographic plates. Each plate represents a unique record of the universe from a time past that can never be repeated.

The Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute (PARI) in North Carolina has proposed a plan to ensure the safety of the astronomical photographic collections in North America and to digitize each plate for future generations to use.

The first step is to establish a list of priorities for United States collections at risk. The project was described at the 205th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in San Diego in January.

“The photographic records are in serious jeopardy and a call to the international community to safeguard this priceless wealth of photographic data, some dating back over a century, has been made,” said Michael Castelaz, Director of Astronomical Studies and Education at PARI. “It’s a unique legacy left by previous generations of astronomers.”

Full article here:

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2011/07/pluto-photographic-plate.html