My first glimpse of Ganymede ran like this:

Three dead men walked across the face of hell. Their feet groped past frozen rock, now and then they stumbled in the wan light, and always they heard the thin, bitter mumble of wind and felt the cold gnawing at their flesh. Around them there was death, naked stone reaching for a cruel sky of stars, a lean, poisonous whirl of snow which was not snow, that whipped about them and then lay still to crunch under their tread. Jupiter was low in the south, a great shield which glowed amber.

That’s not today’s Ganymede, but a mid-1950’s version as seen in Poul Anderson’s The Snows of Ganymede (Ace Books, as part of an Ace Double that included Anderson’s War of the Wing Men, otherwise known as “The Man Who Counts”). I bought this off a newsstand in St. Louis and remember reading it while waiting for a sandwich to arrive at a lunch counter just off Clayton Rd. I would have been something like nine years old.

That memory made the recent news about mapping Ganymede irresistible. It’s not the place Anderson imagined, but then just count how many other surprises we’ve had from our deep space probes. Voyager and Galileo data have come together to hand us a view of Ganymede that tells us where our imaginations strayed, but as we saw in the rest of the Jovian moon system, Ganymede was hardly the first place that didn’t fit what we expected. Think of that billiard-ball smooth face of Europa, and the startling volcanoes of Io.

What we have here is the first global geological map of Ganymede, the largest satellite in the Solar System (it’s larger than Titan, and for that matter, the planet Mercury). This is a world 5262 kilometers in diameter, the only satellite known to have a magnetosphere. The map displays geological features that help us understand how the moon has evolved over the years, not only internally but also through interactions with other Galilean satellites and in terms of objects striking its surface.

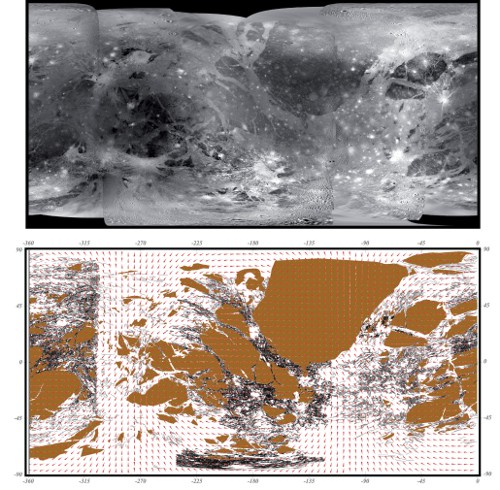

The team, led by Wes Patterson (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory) combined low-resolution photos from Voyager with high-resolution Galileo imagery to create what we see below:

Image: (top) A global mosaic of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede, constructed from the best images collected during flybys of the Voyager 1, Voyager 2, and Galileo spacecraft.

(bottom) A few layers of the geologic map of Ganymede, showing the boundaries between light terrain (white) and dark terrain (brown), and the massive number of tectonic features in the light terrain (black lines). The map is being used to analyze stress fields that could have been responsible for ripping apart the surface of Ganymede in the past (red arrows). Credit: Wes Patterson/JHUAPL.

Here’s Patterson on the significance of this result:

By mapping the entirety of Ganymede’s surface, we can more accurately address scientific questions regarding the formation and evolution of this truly unique moon. Work done using the map by collaborator Geoff Collins at Wheaton College, for instance, has shown that vast swaths of grooved terrain covering the surface of the satellite formed in a specific sequence. The details of this sequence tell us something about the forces that must have been necessary to form those swaths.

If we do get to the Europa Jupiter System Mission, now in the conceptualizing and planning stage at NASA and ESA, we’ll be looking at a Ganymede orbiter as well as one around Europa. This early geological map will clearly be of use in that scenario, helping scientists characterize the moon in detail. The work was presented at the European Planetary Science Congress in Potsdam on the 16th.

So now we have the third completed map of a Moon, the first two being our own Moon and the second Callisto. As to The Snows of Ganymede, it’s well worth a read even today, at least for those of us who love most of Anderson’s work, unraveling as it does political intrigue and mystery on the distant Moon. It’s also hard to find, appearing (to my knowledge) only in the Ace venue and in an earlier issue of Startling Stories (Winter, 1955). Worth seeking out if you happen to be in a used bookstore, that rapidly disappearing artifact of an earlier time.

Hi Paul

Another version of the old Ganymede was James Blish’s in his collection “The Seedling Stars” – a collection of his ‘pantropy’ stories about humans being genetically engineered for life on new worlds. Humans are engineered to live on that frozen, ammonia atmosphered icy moon – but to their adapted eyes it’s as homey as Earth, and Earth is, to them, a place with too much air, water and heat.

I miss the old Ganymede and the old Jupiter. But I’m intrigued by their replacements…

It looks like used copies are available using AbeBooks.com. But if you’d prefer picking up a Ganymedeian story at your local B&N I’d recommend Farmer In The Sky by Heinlein.

Hi Curt

There’s another quite different Ganymede too. Dense enough to have 1/3 of a gee and not too icy, unlike the much icier real Ganymede. Funny thing is the probable low density of Ganymede and Callisto has been known for decades thanks to early studies of gravitational perturbations between the Galilean moons, but no one seems to have quite believed the figures right up into the 1970s. Incidentally Heinlein’s size of Ganymede was ~2,632 km, almost spot on. The early astronomers of the 20th Century could get some surprisingly good results using micrometers to measure sizes on images on their view lenses.

BTW that’s Ganymede’s radius I’m quoting as ‘size’.

Curt, the science in FitS is pretty dubious. Ganymede terraformed in a few decades, by use of force fields, supermoonquakes caused by the moons lining up… well.

I’ve never quite understood why Ganymede lacks an atmosphere. Yes, it’s hotter than Titan, but “hot” is pretty relative out there. And a BOTE calculation suggests it should have been able to retain ethane if not methane. I’m sure there’s a good reason, but I’ve never seen it spelled out.

Doug M.

Forget being amazed at having a detailed map and other information about

an alien moon over 400 million miles from Earth – according to that SF

novel cover, they used to offer two complete stories for just 35 cents!

Unbelievable!

So how deep under the ice might the conjectured Ocean of Ganymede be?

Hi All

Doug M., Jay Melosh’s work on impact erosion of atmospheres shows that Ganymede (and the other Galileans) would lose atmosphere, while Titan gains it, because of their relative difference in gravitational potential. He did see a trace atmosphere of methane/ammonia remaining on Callisto, but it would’ve been decomposed and polymerised in the high-energy particle environment Callisto is in. Thus the atmosphere’s remnants are probably the dark material on Callisto’s surface – long-chain frozen hydrocarbon gunk.

Larry, I’ve seen estimates that put Ganymede’s ocean some 10-20 km below the ice at the peak of the heating that led to its present-day terrain. How much deeper it is now I’ve no idea. Deeper than Europa’s definitely. But there are a few odd mascons so maybe a great mass of ‘warm ice’ or even buried sea might be closer to the surface in places, rising through the surrounding ices like a balloon of magma in Earth’s crust. Depends on the solutes in the liquid. All sorts of odd salts are possible.

Hi Folks;

5,262 kilometers in diameter! DAAaaM! I did not know that Ganymede was so large. This moon might be used for a complex of sub-surface and surface based habitats with enclosed regulated atmospheres. If we built in three dimensions, a many layered or should I say, storied sub-surface civilization might flourish on Ganymede, as well as on the potentially several other suitable moons in our solar system.

I hope the Europa Jupiter System Mission goes through with great success. We have somewhere around 200 moons in our solar system to explore. I look at such future exploration and possible development of these moons as a sort of ride to a proverbial vacation site that is essentially the entire Milky Way Galaxy and beyond.

Part of the fun of going on a road trip for me is the drive to the point of destination. If we could travel anywhere all at once, that would indeed be cool, but we would loose out on the fun and novelty of the long road trip to the destination. In this case , the future of manned intersteller travel within the Milky Way and beyond is an eternal vacation destination full of disovery, while the first road traveled on to this destination is the road of exploration of our solar system. I hope and feel that we will discover many things along this road.

Adam, that’s very interesting! Is there a reference I could look at? Now I’m curious.

Thanks,

Doug M.

Hi Doug

My summary comes from an old “Discover” magazine article on his work. Now that I’ve searched for it I’ve found it was Zahnle and Griffith who did the Galilean/Titan modelling. Here’s the “Discover” piece…

http://discovermagazine.com/1995/jun/themarsmodel522/

…and the paper by Zahnle and Griffith…

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1992Icar…95….1Z

Wrong paper. But akin to the one by Caitlin Griffith and Kevin Zahnle, which is here…

http://www.lpl.arizona.edu/faculty/griffith/eprints/Griffith95.pdf

…but I doubt the findings are very different.

Do you think humans will ever make it to Jupiter space?

Differences Between Ganymede and Callisto Explained

http://srs.gs/1279

“Differences in the number and speed of cometary impacts onto Jupiter’s large moons Ganymede and Callisto some 3.8 billion years ago can explain their vastly different surfaces and interior states, according to research scientists.”