Saturn’s moon Iapetus has always had an unusual aspect, one first noted all the way back in the days of Giovanni Cassini (1625-1712), for whom our Saturn orbiter is named. The moon’s discoverer, Cassini correctly noted that Iapetus had a bright hemisphere and a dark one, each visible (because of tidal lock) on only one side of the planet as viewed from Earth. We now call the dark hemisphere Cassini Regio in honor of the Italian-born astronomer.

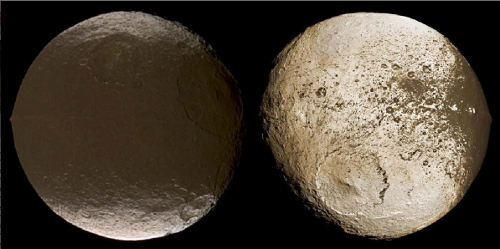

Image: Cassini-Huygens spacecraft images of Iapetus’ dark, leading side and its bright, trailing side. The high-resolution images shed new light on the long-standing puzzle of how Iapetus got its unusual coloration. Credit: Cassini Imaging Team.

So what makes Cassini Regio so dark? Interior activity on the moon itself is one possibility, but the leading theory is that dusty debris from Saturn’s moon Phoebe is the source. Now images from the Cassini orbiter have been analyzed, with a paper in Science concluding that Cassini Regio is being bombarded by debris from Phoebe. The images can show impact craters down to a resolution on the order of 10 meters to the pixel. Small bright craters are found within the dark hemisphere that indicate the dark surface material is likely only a few meters thick. Moreover, both dark and bright materials on the leading side are much redder in color than on the trailing side.

The leading side’s dust, in other words, seems to have come from somewhere else. Moreover, the transition from dark to light hemisphere is shown to be not a solid line but a mottled array of dark and light spots. Couple this with recent work in Nature that announced the discovery of an enormous ring of debris ten thousand times the area of the main ring system, around Saturn and near Phoebe, a system that supports the dust from Phoebe hypothesis. It is thought that impacts on Phoebe keep the ring supplied with material, and that this material then migrates inward to strike the dark side of Iapetus.

Joseph Burns (Cornell University) thinks the dust question has been resolved:

“The ring of collisional debris that has come off Phoebe is out there, and its companion moons are out there, and now we understand the process whereby the stuff is coming in. When you see the coating pattern on Iapetus, you know you’ve got the right mechanism for producing it.”

Remember that Iapetus is hardly alone when it comes to dark material being found on the surface. Not long ago we looked at studies showing black coatings on Hyperion, Dione and Phoebe as well, suggesting a common mechanism for carrying the material from one moon to another. That work was intriguing because there’s some evidence for geological activity on Dione, but evidently not enough to serve as the source for its dark materials. Here I’m going to repeat a quote I used earlier from Cassini scientist Bonnie Buratti:

“Ecology is about your entire environment — not just one body, but how they all interact. The Saturn system is really interesting, and if you look at the surfaces of the moons, they seem to be altered in ways that aren’t intrinsic to them. There seems to be some transport in this system.”

Indeed, and with Cassini’s help we’re untangling its mysteries. The paper is Denk et al., “Iapetus: Unique Surface Properties and a Global Color Dichotomy from Cassini Imaging,” published online in Science on 10 December, 2009 (abstract). The paper on the ring discovery is Verbiscer et al, “Saturn’s largest ring,” Nature 461, (22 October 2009), pp. 1098-1100 (abstract).

I first heard about Iapetus’s puzzling asymmetry in an old comic reprint – the enhanced albedo was from diamonds, which was as good a guess as any in 1953. Now we know better and the answer is perhaps more prosaic than Iapetus’s other mysteries like its orbit and equatorial ridge… but I wouldn’t count on there being no more surprises either. Something weird happened amongst Saturn’s moons – perhaps Titan disrupted other moons when (if) it was captured?

Apologies if the link below is too OT. Some posters have expressed an interest in the search for alternative forms of life, including ones that may exist or have existed on Earth:

http://www.mso.anu.edu.au/~charley/papers/DaviesetalShadow.pdf

http://www.technologyreview.com/blog/arxiv/26752/

Astronomers Solve the Mystery of the Ridge around Iapetus

The mysterious ridge around the equator of Iapetus is probably an ancient ring that settled onto the surface of the moon, say planetary geologists.

kfc 05/11/2011

Saturn’s moon Iapetus is one of the more mysterious objects in the Solar System. It’s fairly large, the 11th largest moon in the Solar System, and made mostly of ice.

But Iapetus is a puzzle. Half of the moon is dark-coloured and the other half light, with no shades of grey. It is bulging around its equator, as if it is rapidly spinning. But it actually rotates rather leisurely, once every 79 Earth-days. Most puzzling of all is a ridge that stretches almost half way round its equator (see picture above).

Today Iapetus is slowly giving up its secrets. Planetary geologists recently solved the puzzle of its two-tone appearance. It turns out that the dark stuff is the chemical residue left when water ice sublimates.

The thinking is that about a billion years ago, one side of Iapetus began to sublimate a little more quickly than the other, leaving a dark residue. The ice then condensed on the other side of the moon making it lighter. The darker side then absorbed more sunlight, making it warmer and increasing the rate of sublimation in a positive feedback cycle.

It is this cycle that has left the moon in its current two tone state.

Today, Harold Levison and buddies at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, have hit on an explanation for the other two puzzling features: Iapetus’s bulge and ridge.

Their theory is that early in its history, Iapetus spun very quickly, probably at a rate of once every 16 hours or so. This caused it to bulge around its equator.

At this time it was hit by another large moon, which catapulted a huge volume of ejecta into orbit (a little like the collision that formed our Moon). This orbiting mass of rubble then fell victim to two separate processes.

To understand these forces, we first need a little bit of background about orbital dynamics. Astronomers have long known that there is a particular distance from any gravitational object beyond which rubble can condense to form a solid body. This is called the Roche radius. However, anything closer than this gets torn apart by tidal forces and so never condenses.

Levison and co say the ejecta around Iapetus must have spanned the Roche radius. The stuff beyond this limit condensed to form a new moon, which gradually spiralled away from Iapetus. It was this loss of its own satellite that slowed Iapetus’s rotation to the sedate rate we see today. However, its frozen body preserved the shape of the original bulge.

But the ejecta inside the Roche radius could not have formed a solid body and so must have formed a ring around Iapetus instead. Levison and co think this ring was unstable and must have slowly closed in on the moon.

So the equatorial ridge we see today is the leftovers of this ring that settled onto the moon’s surface.

That looks like a neat idea. It explains at least two of the great mysteries of Iapetus. And that ain’t bad for a single theory.

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/1105.1685: Ridge Formation And De-Spinning of Iapetus Via An Impact-Generated Satellite