I’m always sorry when a good conference like the Royal Astronomical Society’s 2010 gathering ends, even if I’m attending it ‘virtually’ from the other side of an ocean. But virtuality has its advantages, as I’m reminded by several conference attendees who have struggled with Icelandic volcano ash when trying to book flights out of the UK. If I were with them in Glasgow, I’d praise my good fortune for extra time in Scotland and immediately take the train for Inverness, then on to Skye and the Inner Hebrides, where I’ve spent many good days and intend to spend many more.

Volcanic ash or no, it was a lively conference with tantalizing results on planetary system residues in white dwarfs and retrograde exoplanet orbits, and a number of other issues that can be found in the conference program. I’ll close our RAS coverage here with two items that deal with interstellar dust rather than the Earth-based dust and ash that closes airports. Red giants, the kind of star our Sun will eventually turn into in a later phase of its life, expel dust and gas that produces raw materials for a new generation of stars and planets. The outcome is often a beautiful nebula, but it can also be a dusty disk surrounding what the red giant finally becomes, a white dwarf.

Dusty Disks Around Aging Stars

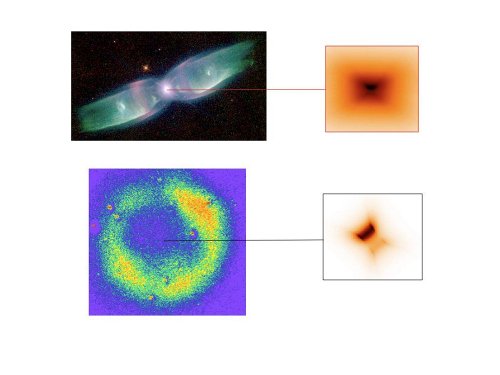

The new work pegs disk formation around stars at various stages of their evolution, an outstanding question being how long these disks survive. The images Foteini Lykou (Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics) showed at the RAS session were of disks caught early in their lives. M2-9 is a striking example, a nebula with symmetrical lobes of gas extending from it, with a binary star system at its heart. A red giant and a white dwarf are hidden by the disk, the dust originating in the red giant. Lykou believes the disk inside M2-9 is less than 2000 years old, a startling figure given the usual time-scales of astronomical observation.

Image: Top: Bipolar nebula M2-9 (credit: B. Balick/HST) with a reconstructed image of its dusty disc observed by VLTI. Bottom: Round nebula around Sakurai’s Object (credit: A. Zijlstra, University of Manchester) with its corresponding disc.

But the disk around Sakurai’s Object, a round nebula some 11,400 light years from Earth, is even younger. It’s composed of amorphous carbon (think coal or soot) and is growing rapidly. Says Lykou:

“The disc in Sakurai’s Object was created within the last 10 years, so we have the opportunity to study a newborn disc. It is expanding radially — and rapidly — in space. During our observation period in 2007, we saw the disc extend from 10 thousand million kilometers to 75 thousand million kilometers.”

We’re still speculating on what happens to these disks but current thinking is that interstellar radiation probably breaks the constituent dust grains down and thereby replenishes the interstellar medium with new materials. Observing objects like these calls for interferometry, combining the light caught by multiple instruments to sharpen the field of view. The astronomers here used the Very Large Telescope Interferometer at the European Southern Observatory in Chile, which combines four 8.2-meter telescopes and works in the infrared.

Explaining Interstellar Water

I’ll close our RAS coverage with a different kind of look at interstellar dust, one that helps to explain where water from the interstellar medium comes from. The problem is that while hydrogen atoms are extremely common in deep space, little gaseous molecular oxygen (O2) seems to be available and ozone has not been detected in these regions. Atomic oxygen (O) is plentiful, but gas phase reactions between hydrogen and atomic oxygen cannot account for the amount of water observed. Moreover, even the observed amounts of atomic oxygen show a shortage in star-forming regions when compared to the rest of interstellar space.

So while it’s one thing to say that Earth’s water was delivered by comets formed from interstellar material, the question of where that water came from in the first place has remained unanswered. And just where is the missing atomic oxygen?

Enter Victoria Frankland (Heriot-Watt University), whose team of researchers think they have found the answer in the form of the dust grains that make up approximately 1 percent of the interstellar medium. The dust, Frankland believes, provides the surface that allows the needed reactions to take place. Some molecules remain stuck to the surface so that an icy coat — mainly water ice — builds up over time. Says Frankland:

“These initial experiments are having some interesting results in that they are allowing us to look at how the ice coating develops on the dust particles. It appears that oxygen atoms may become trapped inside the icy mantles. We need to do more work, but it could be that our experiments might help solve the mystery of the missing atomic oxygen as well as where the water has come from.”

The image below is too beautiful not to run:

Image: Molecular cloud and star-forming region in the interstellar medium. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/L. Allen (Harvard-Smithsonian CfA).

Interstellar dust is gorgeous to the eye when lit up in star-forming regions like this one, and we’ve often speculated here on the problem of such dust for fast moving spacecraft of the far future. Now we’re learning how dusty disks can form not just around young stars but around burnt out stars nearing the end of their fusion reactions. And we’re seeing that dust may play a role in the essential production of water, so necessary for the formation of life. How appropriate, then, that volcanic ash and dust should mark the end of the illuminating sessions in Glasgow, a reminder that scientific theory paints a real and sometimes all too frustrating world.

Where can I find a large version of the molecular cloud image?

Hi Paul;

The above dusty image is increadibly beautiful. Such images seem to strike to the core of my conscious identity. My mother, who is also fascinated by astronomy and who often asks me what we practicianers of Tau Zero are up to will say the same thing when I present her with a good astrophotograph. From an abstract intellectual standpoint, I find it amazing at times the effect that such photos can have on our psyches. It is almost as if nature, the cosmos, or perhaps the whole of existence is somehow calling us out from the cradle of Earth. Art work such as the above dusty cloud scene will no doubt in itself promote the cause of we practicianers of Tau Zero.

I read your blog as often as I can. One of my favorite website. Thanks for your work.

But I noticed that when you post beautiful pictures like the one above, you only post the re-dimensioned picture, could you also post a link to the biggest version available ? Please :)

I know we can find everything, or almost, on Hubble’s website (or the NASA’s one), which are great, but also a bit messy.

Good point, TK_AK. One reason I stopped linking to the larger versions is that they so often get taken down, so that the link becomes useless after a few weeks. But when I can find a stable version of a given image, I’ll be glad to link to it. I agree that it’s a good idea.

Eniac, try this link. I just linked the above molecular cloud image to it:

http://ipac.jpl.nasa.gov/media_images/ssc2005-23a1.jpg

And for more pictures of this type, NASA’s Astronomy Picture Of The Day is a great source.

http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/archivepix.html

As beautiful and intreging as the molecular cloud image is, I often like to think what it is really like if I was in it. For the most part is it not just slightly less of a vacuum as dark areas. It is our distance away from it and the consolidation of light in a large object made small by distance that gives it the amazing image.

I believe that this particular molecular cloud has been named “The Eagle” for obvious reasons. It’s as iconic and evocative as the Horsehead in Orion. It does make you yearn, doesn’t it?

As superb as the research, reporting and writing may be, it is the pictures that really make it worth coming here.

Thank you for the kind words, Eniac. Much appreciated!

Thanks for the mention.