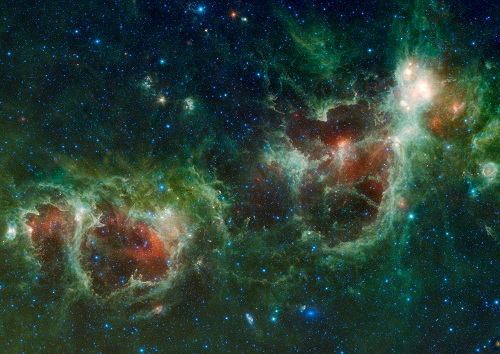

What a glorious image WISE has given us. The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer has finished three-quarters of its infrared map of the entire sky, with the final images scheduled for July, after which time the spacecraft will spend three months on a second survey before its solid-hydrogen coolant (needed to keep its infrared detectors chilled) runs out. The public WISE catalog will be released a little over a year from now, but we can already marvel at spectacles like the Heart and Soul nebulae, seen below. Be sure to click on the image, presented at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Miami, to enlarge it and spend some time among the newly forming stars.

Image: Located about 6,000 light-years from Earth, the Heart and Soul nebulae form a vast star-forming complex that makes up part of the Perseus spiral arm of our Milky Way galaxy. The nebula to the right is the Heart, designated IC 1805 and named after its resemblance to a human heart. To the left is the Soul nebula, also known as the Embryo nebula, IC 1848 or W5. The Perseus arm lies further from the center of the Milky Way than the arm that contains our sun. The Heart and Soul nebulae stretch out nearly 580 light-years across, covering a small portion of the diameter of the Milky Way, which is roughly 100,000 light-years across. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA.

The beauty of WISE for this kind of study is that it’s working in the infrared, and thus able to penetrate into cool, dusty crevices in the dust surrounding these star factories. It’s important, then, to keep in mind that we’re not in visible light here. In this image, green and red (mostly light from warm dust) represents light at 12 and 22 microns, while blue and cyan show infrared at wavelengths of 3.4 and 4.6 microns (dominated by light from stars). With that caveat in mind, we can marvel anew at the prodigious spectacle that accompanies stars being born.

No word yet on the brown dwarf possibilities in nearby space, of particular interest to Centauri Dreams readers, but we’re getting no shortage of images, with some 960,000 having been beamed down to date. And let’s not forget WISE’s utility in spotting asteroids. The spacecraft has tagged 60,000 of them thus far, of which about 11,000 are newly discovered, and 50 of these are near-Earth objects, of obvious significance as we continue to identify potential impact threats. The NEOWISE program studies and catalogs the asteroids WISE is finding.

“Our data pipeline is bursting with asteroids,” said WISE Principal Investigator Ned Wright of UCLA. “We are discovering about a hundred a day, mostly in the Main Belt.”

Once identified, new asteroids are reported to the IAU’s Minor Planet Center in Cambridge MA, and a network of ground-based telescopes follows up and confirms the finds. Although it hasn’t yet found an asteroid that would be too dark for visible-light detection from the ground, WISE’s infrared capabilities give it more accurate measurements of an asteroid’s size. Researchers expect that by mission’s end, WISE will have found between 100 and 200 new near-Earth objects and will offer size and composition profiles for all.

Two aspects of the WISE mission particularly pique our interest at Centauri Dreams. Tracking down thus far unidentified brown dwarfs near the Sun is obviously consequential — a brown dwarf at 3 light years would make a tempting target for study and, one day, an interstellar probe, being closer to us than the Alpha Centauri trio. But WISE also investigates the Trojan asteroids, which track Jupiter’s orbit around the Sun in two groups, one in front of and one behind the giant planet. 800 Trojans have been observed thus far, and their study may offer insights into the formation of gas giants both in our system and in others.

In terms of protecting our planet, WISE is also a comet hunter, having seen more than 72 so far, a dozen of them new. This animation gives you a sense of WISE’s operation, showing as it does the objects that come near the Earth, along with the comets found thus far. Measuring cometary orbits helps us understand what triggers their movement from long-period orbits (or short-period orbits within the system) and pulls them in toward the Sun. The search for a large, hidden perturber, possibly a gas giant, in the Oort Cloud will benefit from this information, but even in its absence, we need to learn more about how comets move in order to understand how they shaped our Solar System and played a role in bringing volatiles to the Earth.

Were there a means the WISE data could be mined by the public, like Galaxy Zoo, some of us would subscribe to help.

Would be nice if the perturber postulated by Matese & Whitmire gets “discovered” by WISE, especially if it’s big & warm enough to be a BD. If it glows at ~500 K, then a moon receiving ~250 K levels of heating will be ~4 planetary radii out. With a suitable atmosphere and/or tidal heating such a moon would be astrobiologically interesting. Assuming the scaling of moons posited by Robin Canup, Mars sized moons should appear around BDs 5-10 times heavier than Jupiter.

It’s probably a little far out there but is is possible that WISE could detect a Dyson Sphere type object?? I remember reading that these would emit quite a bit of infrared radiation/heat and it might be enough to look unusual when compared to another star/object. I couldn’t figure out from the article if WISE has the resolution needed for this type of detection…

SO COOL!! I love this type of research (ie not my bs but the ACTUAL science they are probably doing).

Is WISE also looking for Trojans associated with other outer planets? Mars and Nepture have some, I think there are dynamical reasons why Saturn and Uranus might not but there’s no harm in looking!

P

My biggest interest in this is finding cool BD’s in the local area. It was mentioned on here a few weeks back that a BD had been discovered this year and it was within the 10 nearest stars.

However, that was found from an older survey (and one that covered only 6% of the sky BTW). It was quite some time after the images became available that this object was found. So my question is, how long will it take to process the images so that we can say definitively there is/is not (delete as applicable) a BD closer than Centauri?

If you click the link at the top of the article, then click

WISE Flash Piece

>Cool Stars

>Close Neighbours

you get a picture of the solar neighbourhood where you can toggle between “present day view” and “the WISE view”. The difference, of course, is all the conjectured BD’s light up in the “WISE view”.

Quite clearly the WISE team expect to see more BD’s than proper stars. There are at least four conjectured BD’s closer than Centauri (at least on the two-dimensional projection).

It is also stated that WISE is expected double or even triple the star count within 25LY (and they are counting BD’s as “stars” of course).

I hope they are not over-stating the case and then we get disappointed !

look like that the WISE already found 2 BD

see at: http://nextbigfuture.com/2010/05/nasa-wise-telescope-has-found-at-least.html#more and

http://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/post.cfm?id=wise-satellite-already-spots-two-br-2010-05-27

Thanks for the news Daniel. It’s a bit disappointing these discoveries are not on the WISE website itself!

WISE-2 sounds like it is under 500K, and going by the claimed detection capabilities, that would mean it is within 75LY.

Also, it is claimed that several hundred BD’s have been discovered, but they have to await confirmation from Spitzer. This makes me put 2 and 2 together and make 5. Why are WISE-1 and WISE-2 selected out of these hundreds? It says their spectra are unambiguous but their distance is unknown, I wonder if these two are very close by but they are waiting to make sure?