While lamenting the budgetary problems of space-based missions like SIM — the Space Interferometry Mission — I often find myself noting in the same breath that technological advances have us doing things from the ground we used to think possible only from space. Make no mistake, we need to develop space-based interferometry for future studies of exoplanet atmospheres and their possible biomarkers. But it’s gratifying that the next generation of ground-based telescopes using adaptive optics coupled with extremely large instruments like the Giant Magellan Telescope will also give us powerful tools for studying exoplanets.

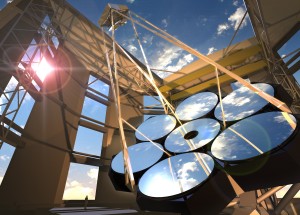

Image: An artist’s rendering of the Giant Magellan Telescope in its enclosure. Credit: Giant Magellan Telescope Organization.

The same holds true for another intriguing line of investigation. We’ve known about dark energy since the late ’90s, when two groups — the Supernova Cosmology Project and the High-z Supernova Search Team — discovered that the expansion of the universe is accelerating. It’s now believed that dark energy makes up some 70 percent of the mass and energy of the universe, a startling thought given that we know almost nothing about it. No wonder dark energy is considered by many the most significant problem facing physics today.

Pursuing its nature is something we can do in space, as we saw yesterday in discussing the WFIRST mission advocated by the National Research Council’s Decadal Survey. But we can do a great deal from the ground as well. HETDEX (the Hobby-Eberly Telescope Dark Energy Experiment) is a project to discover what dark energy is. An upgrade to the Hobby-Eberly Telescope run by the University of Texas at McDonald Observatory, HETDEX has just received an $8 million grant from the National Science Foundation to survey dark energy.

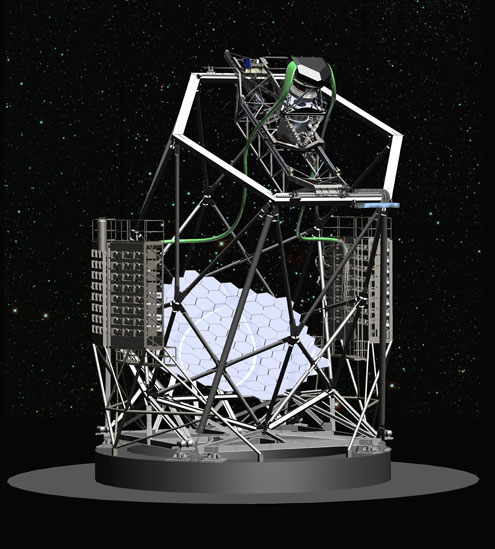

Here’s the method: HETDEX will make a survey of approximately one million star-forming galaxies between 10 and 11 billion light years away. The goal is to study these findings to learn whether dark energy is constant through time. At the heart of the survey is a spectrograph called VIRUS, to be assembled and aligned at Texas A&M University. VIRUS will be made up of 150 copies of a single spectrograph, allowing it to capture spectra from 33,000 points on the sky simultaneously using fiber optics to move light to the spectrograph array.

Image: Artist’s concept of the upgraded Hobby-Eberly Telescope. The VIRUS spectrographs are contained in the curved gray “saddlebags” on the side of the telescope. They receive light through the green cables, which contain bundles of fiber-optic lines. This illustration shows the telescope without its enclosing dome. Credit: McDonald Observatory/HETDEX Collaboration.

In making this survey, HETDEX also opens up an extremely useful window on the early universe. Says Robin Ciardullo (Penn State):

“The HETDEX observations, in addition to revealing key information about the expansion history of the universe, will also provide important insights into the formation of galaxies. We will be obtaining information from a time before our sun was born. We believe that many of the objects HETDEX detects will someday evolve into galaxies similar to the Milky Way, so the experiment will also be providing a glimpse into our galaxy’s infancy.”

The HETDEX survey is to begin in January of 2012 and, according to reports from project partners, is currently on track. After three years of operations, the survey will cease, with data being released to the public. Thus HETDEX joins existing dark energy projects like the Dark Energy Survey (Fermilab) and the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (part of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey). Will a firm fix on dark energy emerge from one or more of the three? Let’s hope so, for understanding what makes the cosmos accelerate is fundamental to physics.

Ultimately, the ability to make such surveys using space-based instrumentation holds out the promise of going even deeper into these mysteries, but it’s heartening that as we survive economic downturns and build toward an eventual space infrastructure, we can accomplish so much from our planetary surface. Learning what makes the universe tick is an end in itself, but there’s also the tantalizing possibility that at some point in the future, we’ll learn whether there is an energy here that can be put to work to turn a system-wide space-based infrastructure interstellar.

Someone remind me again:

Dark matter is needed to explain the observed rotation of the galaxies. Also, dark matter can’t be normal matter because if it was it would block out more the star light reaching us than is the case. Is this correct?

Dark energy is needed to reconcile recent astronomical observations with the Big Bang Theory. Is this correct?

kurt9, yes, dark matter emerged as a way to explain anomalous galactic rotations, but it’s also been studied intensively in terms of gravitational lensing effects — in other words, how a distant object bends light is affected by dark matter. The best book on this is Evalyn Gates’ Einstein’s Telescope: The Hunt for Dark Matter and Dark Energy in the Universe. Gates goes through the recent work and discusses the impressive observational evidence re dark matter, and goes from there into dark energy. About the latter: Supernova investigations indicated in 1998-99 that the universe is not only expanding, but that its expansion is accelerating. It’s that acceleration, again the focus of intensive study, that has scientists trying to come up with explanations.

Dark matter interacts with normal matter only through the gravitational force. So wouldn’t it be wreaking havoc with our observations and calculations of orbits in our solar system and in binary systems, and in every other calculation involving gravity?

“…we’ll learn whether there is an energy here that can be put to work to turn a system-wide space-based infrastructure interstellar.”

Dark energy: fuel for the imagination, but not vehicles.

I am not investing. ;-)

To Stephen:

The density of cold dark matter (CDM), if it exists, would be too sparse at the scale of the solar system or other star systems to induce detectable anomalous orbital velocities. Only at the galactic scale can there be enough CDM to contribute significant gravitating mass.

Having said that, I can also tell you that at an intermediary scale — the scale of globular clusters — once again CDM would be too sparse to induce detectable anomalous orbital velocities, but nevertheless, anomalous velocities at the edges of globular clusters HAVE been reported by the likes of Italian astronomer Riccardo Scarpa, et al. They interpret these observations as evidence for MOND (a modified gravity theory) — which is a rival theory to CDM. However, their findings are also consistent with the theory that merely the Doppler shifts (observed in the spectrographs from which knowledge of velocities depend upon) are anomalous, and that the underlying stellar velocities, if they could be independently measured by non-spectrographic means, would turn out not to be anomalous at all, which would falsify both CDM and MOND.

This repulsive force we see given the name, “Dark Energy,” seems like hocus-pocus! A better name might be Phlogiston II.

Lots of stuff we don’t understand. In a way, that gives me some small bit of optimism that humans will uncover something that will revolutionize propulsion and make interstellar travel feasible.