I had hoped to be able to cover the Hartley 2 flyby today, but I’m traveling on Tau Zero business and have to write this entry early. Instead, I’ll at least keep the EPOXI mission focus by talking about the other half of this unique venture, an investigation of exoplanet systems. We can always talk about what the Hartley 2 encounter produced next week, but not before, as the schedule is crowded and I doubt I’ll be able to get an entry posted here at all on Friday.

Remember that the Deep Impact spacecraft that visited Tempel 1 in 2005 is now on an adventuresome extended mission called EPOXI (although the spacecraft, confusingly enough, still retains the original ‘Deep Impact’ name). The spacecraft was reawakened in the fall of 2007 and directed to a flyby of the Earth for a gravitational assist that would put it into a heliocentric orbit for the Hartley 2 encounter.

On the cruise portion of that journey, the extrasolar component of the mission kicked in. EPOCh (Extrasolar Planet Observation and Characterization) is the name of that investigation, the observing phase of which began in January of 2008 and ran until August of that year. A deep search of a nearby red dwarf star looking for a planet comparable in size to the Earth has been part of the larger EPOCh study.

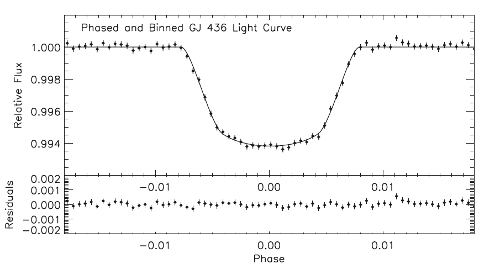

33 light years from Earth, GJ 436 is known to host a Neptune-sized planet that transits every 2.6 days. The fact that GJ 436b’s orbit is slightly eccentric has drawn the attention of researchers interested in whether an unseen planet is behind the eccentricity, perhaps one as small as the Earth. Three weeks of continuous observations produced an excellent lightcurve of the Neptune-class world, but despite the fact that the potential planet was expected to orbit nearly edge-on to our line of sight, no transit or other data signature for it was found.

Image: EPOCh data for the transit of the Neptune-sized planet orbiting the red dwarf star GJ436. Using data of this quality, EPOCh was able to attain sensitivity to planets as small as 1.5 Earth radii. Credit: Ballard et al. 2010, Astrophysical Journal, Vol. 716, p. 1047.

The team is able to rule out transiting planets over 1.5 Earth radii to a high degree of confidence. Even in the absence of a transit, variations in the transits of the known planet could signal the existence of further planets. So is there a GJ 436c, or is there some other explanation for the eccentricity of GJ 436b’s orbit? Drake Deming, deputy principal investigator for EPOCh), has this to say in a post on the EPOXI site:

[The] negative result has provided motivation for theorists to consider that GJ436c may not exist. Theorists are re-examining their original conclusion that the orbital eccentricity of GJ436b requires the presence of a second planet. It is possible that tidal forces from the star are not sufficient — even in the absence of a second planet — to quickly drive the orbit of GJ436b to a circular state, as had been previously believed. That would obviate the need for GJ436c, but would require the interior structure of GJ436b to be unlike the gaseous planets of our solar system.

GJ 436 is one of eight stars chosen for the original EPOCh survey, all known to have other transiting planets. The other transiting planet systems included HAT-P-4, TrES-2, TrES-3, XO-2, GJ436, WASP-3, and HAT-P-7. In addition to finding new worlds, intense study of the known transiting planets could reveal the existence of moons or rings around the planet. The EPOCh team has now moved from processing the data to writing papers about the results.

But EPOCh isn’t through yet. Using the same data analysis technique developed for the mission and employed with GJ 436 data, researchers will soon be working with data from the Spitzer Space Telescope. The Deep Impact spacecraft may have Hartley 2 in its sights, but the EPOCh team will be looking to Spitzer’s investigation of the red dwarf system GJ 1214, some 42 light years from Earth. The Spitzer search, to be conducted in the spring of 2011, targets the habitable zone around this star, and the analytical tools developed for EPOCh coupled with Spitzer’s results could theoretically detect a planet here that is even smaller than the Earth.

Thus a spacecraft designed to drive an impactor into a comet — and one that has been re-purposed for a second comet encounter — produces exoplanet data and new analytical techniques that will now mesh with results from a space-based telescope (not to mention its studies of the Earth from space, that provide information about how to observe Earth-like planets at long range). No question about it, Deep Impact has given us plenty of bang for the buck.

You can find more about the EPOCh targets here, and ponder as I do what may turn up in the subsequent analysis of EPOXI and Spitzer data. The paper is Ballard et al., “A Search for Additional Planets in the NASA EPOXI Observations of the Exoplanet System GJ 436,” The Astrophysical Journal Vol. 716, Number 2 (20 June, 2010). Abstract available.

Go EPOCh! Hope they keep it funded for as long as the spacecraft lasts. Any word on how much gas is in its tank for attitude control?