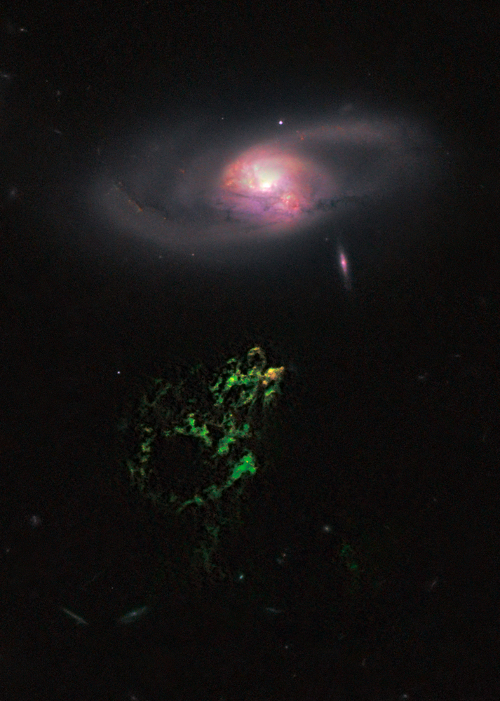

We’re exoplanet-minded around here, and any news from Kepler or CoRoT almost automatically goes to the top of the queue, but there are days when the visuals take precedence. Such was the case yesterday, when even as we learned about a small, rocky planet in Kepler’s view, we also received the image below, released at the American Astronomical Society’s 217th meeting. It’s Hanny’s Voorwerp, named for Hanny van Arkel, the Dutch teacher who discovered the celestial anomaly in 2007 while working with the Galaxy Zoo project. Here it’s seen through the Hubble Space Telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 and Advanced Camera for Surveys, and what an image it is.

Image: This bizarre object, dubbed Hanny’s Voorwerp (Hanny’s Object in Dutch), is the only visible part of a 300,000-light-year-long streamer of gas stretching around the galaxy, called IC 2497. The greenish Voorwerp is visible because a searchlight beam of light from the galaxy’s core illuminated it. This beam came from a quasar, a bright, energetic object that is powered by a black hole. The quasar may have turned off about 200,000 years ago. Credit: NASA, ESA, W. Keel (University of Alabama), and the Galaxy Zoo Team.

This green, gaseous blob floating in space near a spiral galaxy looks for all the world like the cover of a science fiction magazine — I can almost imagine a couple of story titles and a publication name superimposed over the image. What are we looking at? Evidently the nearby galaxy (IC 2497) produced a quasar that sent a beam of light in the direction of the object — the bright green color comes from glowing oxygen. What makes the image so remarkable is that the quasar itself evidently turned off in the ‘recent’ past, within 200,000 years or so, so Hanny’s Voorwerp displays for us the quasar’s afterglow, along with now visible signs of star birth in the galaxy-facing region.

William Keel (University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa) led the Hubble study:

“This quasar may have been active for a few million years, which perhaps indicates that quasars blink on and off on timescales of millions of years, not the 100 million years that theory had suggested.”

Adding to the eerie quality of the photograph is that while Hanny’s Voorwerp seems to be an island of gas floating in space, it’s now known through radio studies that it is part of a long, twisting rope of gas, a 300,000 light-year long tidal tail that wraps around the galaxy, with only the Voorwerp itself being optically visible. All this points to a billion-year old galactic disruption in IC 2497, which is about 650 million light years from Earth. A possible culprit is a galactic merger, which would have expelled gas from the galaxy while simultaneously funneling gas and stars into a central black hole, which would have powered up the quasar.

Small Planet, Hot Orbit

A feast of ideas and imagery inevitably marks each AAS meeting, which makes following the proceedings on Twitter (search for #AAS217) a lively pastime, and one that can become a fixation as the tweets pick up their pace. The action was fast and furious yesterday not only as William Keel’s session on Hanny’s Voorwerp approached, but also when the Kepler mission confirmed the discovery of a small rocky planet, Kepler 10-b. We’re starting to see the emphasis on small planets pay off, as this latest find is said to measure roughly 1.4 times the size of Earth.

But we’re still not talking about a planet in the habitable zone, for Kepler 10-b orbits its star at a distance some 20 times closer than Mercury is to our Sun, with an orbital period of 0.84 days. Because high frequency variations in the star’s brightness caused by stellar oscillations (‘starquakes’) can be readily detected on this bright star, its properties are under active study and help to tell us more about the new planet. Scientists believe that it’s a rocky world with a mass 4.6 times that of Earth, with an average density of 8.8 grams per cubic centimeter. That points to a higher metal content than Earth, and a composition of solid silicate and metal grains.

Here’s Kepler mission co-investigator Natalie Batalha (San Jose State) on the find:

A Science News story quotes Diana Valencia (Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) as saying “I would call it a rocky planet, and I would say it is more like a super-Mercury” than a super-Earth. With temperatures hot enough to melt iron, the star-facing side of the planet is likely covered with seas of lava.

For all the good news that the discovery represents — and it’s a heartening sign that Kepler is on course to find those rocky planets in the habitable zone that so many believe are out there in abundance — Kepler 10-b is not, as is being widely reported, the smallest planet ever discovered outside our Solar System. That honor goes to PSR B1257+12A, a ‘pulsar planet’ some 980 light years away in the constellation Virgo. That object is about twice as massive as our own Moon, a small planet indeed, but the same pulsar has yielded an even smaller candidate, PSR B1257+12 D, which is more or less the size of a Kuiper Belt object in our own Solar System.

True, pulsar planets circle stellar remnants and are obviously well off the main sequence, but they do give us interesting confirmation of the ubiquity of planetary systems. Meanwhile, the hunt for small, rocky worlds with climates far more moderate than Kepler 10-b continues.

Beautiful image.

So the Voorwerp is a massive amount of intergalactic gas that we would not otherwise be able to see but for the light-echo of a now dead Quasar.

Like a flashlight shining on and revealing what was formerly dark matter (small ‘d’).

Hmmm.

Why do you astronomers have such a ridiculous nomenclature when it comes to metals? Am I to take the phrase “a higher metal content than Earth” just means that this planet may be dryer than Earth, and if so why not just say so? I had previously assumed that “metal content” referred to metalicity and “content of metal” referred to metals as chemists would understand it.

While I’m in a griping mood, helium is one of the only two non-metals to astronomers, and the only element named by astronomers, and what did you name it but “metal of the sun”. Additionally, it is my understanding that the metallic form of hydrogen is more common astrologically than the molecular form. What’s going on!

Usually when the astronomers say the nebula or gas cloud or galaxy looks like some animal or object, I never see it. But this one really does look like a happy jumping frog. It reminds me of that frog from the Bugs Bunny cartoons that used to sing “Hello My Ragtime Doll”.

Dear Paul,

The letter ‘a’ does not apply to exoplanets (PSR1257 12A is the star itself, not the exoplanet).

Regarding exoplanet enciclopedia I would say that PSR1257 12b is the lightest exoplanet known.

http://exoplanet.eu/planet.php?p1=PSR+1257+12&p2=b

To Rob Henry, I’m not sure how to describe Hydrogen’s” astrological” status but I can assure you that anytime spent with basic astronomy books or online astronomy websites would answer your questions and clear up any misconceptions.

Ricardo, this from the Wikipedia should clear up the issue re naming conventions, which are indeed different for pulsar planets (or were):

“The planets of PSR B1257+12 are designated from A to D (ordered by increasing distance). The reason that these planets are not named the same as other extrasolar planets is mainly because of time. Being the first ever extrasolar planets discovered, and being discovered around a pulsar, the planets were given the uppercase letters “B” and “C” (like other planets). When a third planet was discovered around the system (in a closer orbit then the other two), the name “A” was commonly used. The extrasolar planet name 51 Pegasi b (the first planet found around a Sun-like star), was the idea used for naming planets. Although these pulsar planets were not renamed, some have done it themselves. PSR B1257+12A is catalogued as “PSR 1257+12b” on The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia.”

My understanding is that the pulsar designation is PSR 1257+12, not PSR 1257+12A — let me know if I have that wrong.

The Kepler mission website has been revamped and now lists the lastest confirmed exoplanet Kepler 10b and also the aprox. number of planetary candidates.

The Kepler space telescope was down for 15 days while NASA worked out a problem with the Sun detector circuitry. Science operations resumed on Jan.6th.

I would heartily recommend a visit to the Kepler website to learn more about the efforts made to keep Kepler functioning and to read up about Kepler 10b. The smallest exoplanet (1.4 Earth radius) detected around a main-sequence star so far. We can expect a wave of exoplanet discoveries from Kepler and the follow up team this year and over the next few years.

There are thousands of follow up RV observations needed to confirm planetary candidates and that will take time.

Now it is clear to me: the naming convention changed after the discovery of these pulsar-planets…

Thanks Paul for the explanation.

Regards,

Ricardo

To Bob Henry,

In astronomy metalicity has a different meaning.

“What do astronomers consider a metal?

Astronomers consider any chemical element heavier than hydrogen a metal. This is because when the Universe began in the Big Bang the only elements produced in large abundances where hydrogen and helium (the two lightest elements). Stars produce all elements heavier than hydrogen in their cores as a result of the process of fusion by which they produce energy to shine. So all the chemical elements produced in stars are considered metals. ”

Read more on the site below:

https://edocs.uis.edu/jmart5/www/rrlyrae/metals.htm

@Paul Gilster: yes the pulsar planets are indeed designated A to C (e.g. this paper and many others). The fourth object as far as I can tell has never been referred to by designation in the literature and is regarded as unconfirmed. If it exists, it implies that that remarkable system (still the only exoplanet system that looks remotely like our own inner solar system) has formed comets…

@Rob Henry: best fit solutions to the Kepler-10 mass and radius suggest it does have a greater fraction of its mass in the form of an iron core than Mercury does. As for most of the hydrogen in the universe being metallic – nope. Most of the hydrogen in the universe is NOT in the form of gas giant planets…

I completely understand the two different definitions of metal, but in few percent of articles I do not know which one of these two has been used. I think the key here should have been the relative density of 8.8. Unfortunately I do not know how compressed density relates to the uncompressed density of a super-Earth. If the answer is about 6 that density seems incomprehensively high if compared to planets of our solar system. In that case is it even possible to model impacts that would relieve such a world of enough of its rocky mantel without also depleting enough of its metallic core, or are we looking at more exotic processes? I thought that Mercury was the ultimate for this process, but this exceeds it.

I also understand that atomic hydrogen and hydrogen plasma are very much more common that hydrogen metal or molecular hydrogen, but have heard that metallic hydrogen is more common than molecular hydrogen in our universe. Since at the time this speculation rested on unconfirmed assumptions I would love to know if anyone could confirm this.

Obviously Kepler-10b wasn’t born at the distance it orbits its sun now.

.

Probably Kepler-10b lost its light elements to space as it migrated in the direction of its star. Can it explain the reminiscent iron core?

.

See:

http://arxiv.org/abs/1012.1780

ABSTRACT: “The standard picture of planet formation posits that giant gas planets are over-grown rocky planets massive enough to attract enormous gas atmospheres. It has been shown recently that the opposite point of view is physically plausible: the rocky terrestrial planets are former giant planet embryos dried of their gas “to the bone” by the influences of the parent star. Here we provide a brief overview of this “Tidal Downsizing” hypothesis in the context of the Solar System structure. “

what bothers me slightly is the kepler team have yet to extract a signal for less than 1.4 earth radius. We know they must exist in the kepler data and there must be some close enough to their parent star that kepler will have seen many transits of these but as yet no confirmation.

Even out of the 700 or so candidates they announced at the TED presentation none were below 1.5 earth radius. I assume kepler 10b was one of those ok its slight less at 1.4. Is it just a case of fine tuning the software? collecting more data? so far kepler hasnt acheived the sensitivity it set out to do.

Hi Folks;

I was just looking at the above photo of Hanny’s Voorwerp and muzed at the name of this gas cloud. The name Hanny’s Voorwerp standout just as natural wonders on Earth given unique names stand out. Among these are the Yosemiti Park’s Half Dome within the U.S., Mount Everest, The Matterhorn, and the like easily remembered names.

With such a large survey, it is likely that many more novel and exiting things will be discovered and given cool names that scientists and lay-persons alike will easily memorize.

I like the way Hanny’s Voorwerp glows in the shade of green similar to that of Slimer the Ghost, in the movie Ghost Busters. It just looks freaky and out of place. Perhaps this sort of visual qualitative phase change within the subject photo is in itself a sign of novel or exotic initial conditions that lead to the evolution of Hanny’s Voorwerp.

I have been back to this thread about 20 times since its posting just to have a look of the green cloud. This is way too cool.