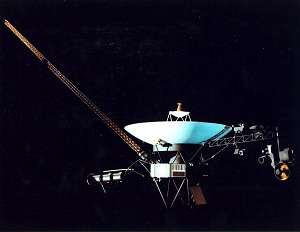

I remember thinking when Voyager 2 flew past Neptune in 1989 that it would be a test case for how long a spacecraft would last. The subject was on my mind because I had been thinking about interstellar probes, and the problem of keeping electronics alive for a century or more even if we did surmount the propulsion problem. The Voyagers weren’t built to test such things, of course, but it’s been fascinating to watch as they just keep racking up the kilometers. As of this morning, Voyager 1 is 17,422,420,736 kilometers from the Earth (16 hours, 8 minutes light time).

Then you start looking at system performance and have to shake your head. As the spacecraft continue their push into interstellar space, only a single instrument on Voyager 1 has broken down. Nine other instruments have been powered down on both craft to save critical power resources, but as this article in the Baltimore Sun pointed out recently, each Voyager has five still-funded experiments and seven that are still delivering data. The article quotes Stamatios “Tom” Krimigis (JHU/APL) as saying “I suspect it’s going to outlast me.”

Deep Space and Human Lifetimes

Krimigis is one of two principal investigators still on the Voyager mission, out of an original eleven, and the only remaining original member of the Voyager instrument team. These days he’s caught up with Cassini work (he’s principal investigator on an APL instrument aboard), but he did find time to report Voyager 1’s findings on the solar wind at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco. These are major observations, the first time since the beginning of space exploration that we’ve come to a place where the solar wind stops.

But tempering that sense of excitement is the fact that we currently have only one mission following up the Voyagers’ path to the outer system, the New Horizons probe to Pluto/Charon and the Kuiper Belt. The Sun‘s article quotes Norman Ness (University of Delaware) as saying that Voyager was the pinnacle of his career. “There is never going to be a mission in anybody’s lifetime, now living, that is ever going to get these observations in hand. So it’s once in a lifetime.” Stephen Pyne makes much the same point in Voyager: Seeking Newer Worlds in the Third Great Age of Discovery (Viking, 2010), leaving us with a reminder that continued expansion into deep space is by no means a given.

But back to the question of mission length and the reliability of parts. What’s fascinating about the Sun‘s article is that it covers Krimigis’ work on instruments that could measure the flow of charged particles during the mission. Such instruments — low-energy charged particle (LECP) detectors — would report on the flow of ions, electrons and other charged particles from the solar wind, but because they demanded a 360-degree view, they posed a problem. From the article:

…Voyager needed to keep its antenna pointed at the Earth at all times, so the spacecraft itself couldn’t turn. That meant Krimigis’ instrument needed an electric motor and a swivel mechanism that could swing back and forth for more than a decade without seizing up in the cold vacuum of space.

“They said I was crazy,” Krimigis said. To spacecraft designers, moving parts spell trouble.

Krimigis argued there was less mission risk in moving one component, than in turning the whole spacecraft. The solution was offered by a California company called Schaeffer Magnetics. Krimigis’ team tested the contractor’s four-pound motor, ball bearings and dry lubricant.

“We ran it through about a half a million steps [movements], enough to take us to Saturn and then some. And it didn’t fail,” Krimigis recalled.

And yes, you guessed it, after more than 5 million ‘steps,’ the instruments are still working. These days they’re working in a region where solar particles no longer strike Voyager 1 from behind, and it’s been like that for the last six months. Krimigis says the instruments can still detect a particle flow, evidently a mix of solar and interstellar particles, moving in a flow perpendicular to the spacecraft’s direction of travel, so it appears we’re still not in true interstellar space, but in a place where, as the scientist puts it, “…the solar wind is kind of sloshing around.”

With the spacecraft now expected to keep transmitting for twenty or so more years, we’ll surely see both Voyagers reach into true interstellar space before their power runs out. Then the loss of energy will take its toll. Somewhere around 2015 Voyager 1 will shut down its data tape recorder, just as Voyager 2 shuts down its gyros. As instruments go quiet, all power will be shunted to interstellar wind measurements and communications with the distant Earth. As we reach 2020, the few instruments still able to operate by sharing power will be unable to be supported. We’ll be left with nothing more than a tracking signal that can last perhaps as late as 2025.

The Decision to Explore

It’s hard to think of these splendid machines shutting down, but ponder that if they make 2025, that will mark almost fifty years of continuous operation for some of their components. The thinking here is that if a vehicle can survive such a lengthy journey without being specifically designed to do so, an interstellar probe built from the ground up to last a century or more should be well within our capabilities. No, it’s not systems reliability that’s the Achilles’ heel of interstellar flight. As always, it’s propulsion, and that other great imponderable: The will to explore.

Only the latter will determine whether the Voyagers really were a single, magnificent gesture or part of a continuum along which our species will move. Is Ness right that we won’t see the Voyagers’ like in our lifetimes? Here again I think of Stephen Pyne’s book, and an assumption that infuses his coverage:

Voyager’s visionaries looked to the future. They thought of the Voyagers as instruments, and assumed their journey was simply another incremental moment in what would prove to be an irresistible expansion over the solar system and beyond. The Grand Tour mission would be followed by more and better missions. They could not know that Voyager would culminate a golden age, that its trek would be unique, that it might require a distinctive narrative. Even the most culturally sensitive such as Sagan looked only outward and forward. They imagined, in Emerson’s phrasing, a continued succession of ‘new lands, new men, new ideas.’

Norm Haynes, who was project manager for the Voyager 2 Neptune encounter, said of the event, “It wasn’t a once in a lifetime experience. It was a one-time experience.” Is he right? Is Pyne right that the Voyagers marked not the beginning but the end of a great era of exploration? These are troubling thoughts to those of us who believe that expanding into the Solar System and beyond is crucial not only for the good of the human spirit but for the very survival of our species. But long-term projects are guided by the decisions and the will of those who conceive and nurture them. The question now is whether we have the will to keep pushing, Voyager style, into the dark.

Our current civilization is not well suited to long range projects and visions like space exploration, nor is our very biology. The vast Cosmos is presenting our species with a challenge: are we capable of greatness? Are we more than hominids in the Olduvai battling with femur clubs? Are we worthy of survival?

My idea for meeting the challenge of space exploration is to turn it into a long term religious imperative. Just as religion made the Egyptian pyramids and the European cathedrals possible, we need to promote a new kind of religion which sees expansion into the Cosmos as a holy mission. I have begun creating a religion along these lines, which I’m calling “Cosmism” — click on my name to find out more about it.

Space exploration comes down to will, which in turn comes down to our fundamental myths. Our species desperately needs to revive the myth of “cosmic manifest destiny” and develop a cosmic religious sense if we are going to continue to progress. Fred Hoyle point out that there is only one shot for intelligent life on our planet — the clock is ticking on our one shot, and our very survival depends on whether we make space exploration a unifying myth going forward or become terminally mired in our terrestrial dramas.

Radioisotope generators. I believe the Mars rovers would have been even more successful if they had employed this technology like the Voyagers and the Vikings, back in the dark ages of the 1970’s.

You can sense that the general will to explore is fading faster than the power supplies on board the Voyagers. This article sadly illustrates this.

However, the fact is that technology continues to move forward at rapid rates. Fewer people and resources will be needed to plan and possibly develop deep interplanetary and interstellar missions someday. So a smaller team of well-funded enthusiasts might very well be able to continue on.

When reflecting on this degree of reliability – damned impressive – I’m just comfortably amazed. This bodes well for the future of starflight.

Throughout history the inventors, explorers, scholars, and dreamers have mostly come from the middle class, whereas the wealthy have been essentially conservative. In the U.S. at least we have been impoverishing the middle class and (further) enriching the wealthy for the last several decades. We are reaping (or not) what we have sown (or not).

Why doesn’t NASA build a “standard” planetary probe instead of re-inventing the wheel each time a new mission is created? In other words, build a standard probe body with stuff that does not change much—-standard radioisotope power supply/optics/gyros/antenna. Then allot the science wizards x number of kilograms for their mission-specific instruments. Then plan a Uranus/Neptune/Pluto orbiter launch for every seven years. The electronics, computers, radios and CCD cameras would be upgraded for each later mission. Wouldn’t that save a lot of money?

A standard Io/Europa/Titan/Triton rover (lots of slashes, I know) could be done the same way. Develop a standard hardware rover chassis and vary the science instruments for the mission.

We (bio beings) probably are just one link in the evolution chain, the next step is machine. For them, low speed, vacuum, cosmic ray, etc involved in the interstellar travel are easier to solve. After all, a machine doesn’t care it will reach the destination in 10 years or 1000 years, as long as it can maintain itself.

This is no different than we found that earth was actually not the center of the universe.

Funny thing. I just got this new map of our galaxy last week in the mail. At least our “local quarter” of it, anyway. If anything, it’s fired up my imagination again. I keep checking on this site, the Kepler mission site, Spaceref’s US and Canadian home pages, exoplanet.eu and a slew of others on a regular basis.

Because the appetite’s never gone away.

I wish there was something poignant yet pithy that I could add to the discussion but nothing comes to mind. I do find the whole business about the prospects for future exploration quite worrisome. The re-primitivization of the world continues and any statement along the line of “If technological advancement continues . . . ,” requires an increasingly large if with numerous qualifications. But should the Technological Singularity* take place in the next generation or two, individual (i.e. small team) explorations should be able to continue, possibly followed by migrations of some sort. But there are so many variables that one can speak of these things only in the most general terms. And it would be much too easy to be pessimistic.

______________________________

* i.e., the future event where hardware costs collapse to the cost of the software needed to design that hardware. Note: Eric Drexler in the late ’80s stated he thought the Technological Singularity would occur place in the early years of this decade. That now seems unlikely.

Frank:

Exactly. Send lots of them, in all directions, so they can form a communications network and extremely long-baseline radio telescope, in addition to their individual missions. Eventually, such a web of probes can bridge the interstellar void.

“Why doesn’t NASA build a “standard” planetary probe instead of re-inventing the wheel each time a new mission is created?”

That’s an interesting question. Is there not enough consensus about the basic features any probe should have? Are the limits elsewhere on how many probes can be built and launched — basic funding, lack of personnel or facilities, shortage of launch vehicles? Maybe unless those problems are addressed first coming up with a standard design is a secondary issue?

Perhaps one day – even though the term “day” will by then cease to hold any particular meaning – one of the Voyager probes will be discovered by some other intelligent animals, long since grown silent and cold yet still obviously the product of a thoughtful, curious civilization. I wonder what will have become of humans when that day arrives, and if Voyager 1 or 2 will be a quaint forerunner of our interstellar advancement or a memorial to what we once were.

“Throughout history the inventors, explorers, scholars, and dreamers have mostly come from the middle class, whereas the wealthy have been essentially conservative. In the U.S. at least we have been impoverishing the middle class and (further) enriching the wealthy for the last several decades. We are reaping (or not) what we have sown (or not).”

Yes. Even leaving out the vast advances in information technology, global production of energy and raw materials is significantly greater than in 1977 when the Voyagers were launched. Humanity has not (yet) been constrained by resource limits, but by a disease of the spirit.

The degeneration of the political economy of the west into a feeding trough for a sociopathic oligarchy has crushed the hopes and dreams of the best and brightest. Not only space exploration, but art, music, and literature have degenerated into crass corporate commercialism. When $14 trillion to bail out private bankers who committed fraud is a given, but $14 billion for a space mission is considered too exorbitant, there is little hope for a renaissance.

Paul, I am not sure your pessimism applies outside the US. Certainly China and

India have expressed interest in interplanetary exploration while Japan and the Europeans have also sponsored such missions and have plans for future ones. As NS has pointed out,

short term thinking currently seems to be more of an issue with the US.

Head over to Project Icarus for some interesting discussion about long term maintenance.

I don’t believe the situation is as bad as it seems. We just need a different approach in financing and the public view, how it perceives space flight. For example if two danes can build a spacecraft for 63,000 $, that they got form sponsors and donations (http://www.copenhagensuborbitals.com/index.php), why can’t we build an interstellar probe for some millions (when the technology allows it).

Everything we need is some advertisement and some ingenious minds to design and launch it!

“That’s an interesting question. Is there not enough consensus about the basic features any probe should have?”

Perhaps the reason we do not build and send more probes is the cost of the ongoing mission support, receiving and doing something with all the data. There is likely a limit to the amount of data we can receive without more expensive infrastructure.

There are insightful comments, all. Indeed, it helps to keep a large historical focus.

There are three forms of chimpanzees: the common chimp, the bonobo, and us. We are the only chimp who got out of Africa. That experience reflects and probably laid down the deep human urge—indeed, our signature: the instinctive desire to restlessly move on, explore, exploit. Natural selection gives us a gut imperative that plays out physically and culturally, our goal: the expansion of human horizons.

Human history has favored both our spatial and our cultural expansion. Fresh prospects yield new perspectives. Life springing from the sea to land was similarly favored. We now stand on a beach, our world, timidly dipping a toe into the sea of space.

We stare into this ocean of night and imagine we are the Columbus generation. I fear we may be the Lief Eriksons.

There should be a bit of pessimism about our lack of Earth to orbit technology. Otherwise I think we’ve just figured out that flying cars at every house, Mars colonies and starships are not going to happen in the very short term. We can do with ground and orbital telescopes vastly more than in the 60’s.

I think we have just reached a sort of most efficient use of technology point that just happens to not include a flurry of deep space probes at the moment. Maybe a better way of saying this would be to ask, “What kind of probes should we be sending into deep space, and why?” Also, is it something that NASA has to fund, or could it be done by the ESA, some university or could it be inexpensive enough to be funded privately?

Voyager certainly is one of man’s greatest achievements of the space age (if not of all time) IMO. The Spirit and Oppy Mars rovers are comparable over-achievers :).

I think the issue isn’t so much “will the machines last” because it seems likely that they will – it’s more “will the funding and earth-based resources last to allow us to keep listening to them”. It doesn’t seem too hard to convince people to spend a little more money to keep receiving data from a hundreds-of-millions-of-dollar mission, but the availability of the Deep Space Network might be a bottleneck.

BTW, I thought Pyne’s book on Voyager was absolutely terrible – I posted a review on my site at http://evildrganymede.net/2010/11/25/voyager-book-review/ . I also posted my own thoughts about Voyager elsewhere on my site too.

Though I am not so sure about a ‘manifest destiny’ or the effectiveness of any new religiousness, I agree with The Cosmist (and others here) that we do need a long-term vision with regard to human future in space, not one based on a mythology or new religion, but one that we determine ourselves.

The main rationales behind such a long-term vision, to be advocated by truly visionary world-leaders, would be two-pronged: sheer survival of our species and civilization, and the spreading of our life in the cosmos. The latter will be hardest to promote and to overcome public indifference, it being rather philosophical in nature. The former is a matter of public awareness.

I think that the combination of the discovery of (potentially) habitable terrestrial exoplanets and some imminent global threats (meteorite impacts, supervolcanoes, new ice ages, etc.) would probably constitute the greatest public incentive for interstellar travel.

@Cosmos great idea count me in ;)

Reality check:

Global space budget in 1975 (constant 2007 dollars, billions)

NASA ~11

USSR ~~5

1975 total: about $16 billion

Global space budget in 2011 (constant 2007 dollars, billions)

NASA ~19

EU ~4.5

Russia ~3.9

China ~~2.0

India ~1.0

Japan ~0.4

Brazil ~0.3

Others (Iran, Pakistan, Israel, Korea, Indonesia) ~~0.6

2011 total: about $31.7 billion

These are rough numbers, but the trend is clear: over the last 35 years, global spending on space exploration has nearly doubled.

We’re living in a frickin’ golden age of space exploration. We’re flying to Pluto, bombing the Moon for water, mapping methane lakes on Titan, and getting ready to land on a comet and drop an SUV on Mars. We’re mapping the inner solar system down to a few meters of resolution and doing sample returns from comets. We’ve got the ISS (which somehow /always/ gets ignored in these discussions), now into its second decade of operation and approved at least a decade more. We’ve got fully functional ion drives, a working prototype solar sail, and the ISS solar panel systems producing enough electricity to light up a small subdivision.

We’ve put landers on Titan and the polar regions of Mars. We’ve watched geysers erupt on Enceladus, lightning strikes on Venus, and found a frickin’ hexagon on the north pole of Saturn.

So: the global space budget has grown steadily for nearly two generations now, roughly doubling over 35 years, with the number of active countries rising from two to around a dozen. As a result, we are currently in a glorious Magellanic age of space discovery.

How are the commenters here responding?

“Quite worrisome… re-primitivization”.

“You can sense that the general will to explore is fading.”

“Disease of the spirit… degeneration… there is little hope for a renaissance”.

“We are reaping what we have sown (or not)”.

“I fear we may be the Lief Eriksons”.

Seriously. What the hell is wrong with you people?

Doug M.

I’m not greatly worried about loss of the will to explore. Everything we do in space must at present leap the hurdle of huge launch costs. The major development of the next couple of decades has to be the appearance of fully reusable vehicles which give economic access to LEO in the service of large-scale markets for the commercial and leisure uses of space (microgravity research and manufacturing, and personal space exploration or space tourism). Companies like SpaceX in America and Reaction Engines in the UK are beginning to make progress on this.

Think forward to a point maybe 20 years on when there may be thousands of private, fare-paying visitors to orbiting space hotels per month. Such an industry is the only way to get costs down and reliability up. At this point, exploration beyond LEO will no longer require such a huge effort of political will. (LEO is halfway to infinity in terms of energy cost, 9 km/s out of 12.4 km/s for Earth escape.)

Ideas about Cosmism, the Millennial Project (Marshall Savage), the Overview Effect (Frank White), my own Astronautical Evolution and so on are nice, but the people who’ll really make the difference are those entrepreneurs working on commercial space access right now. Even the conservative super-rich can help — by buying tickets to fly on the early passenger services and thus building up the industry.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

Doug M: I meant we the USA may be the Lief Eriksons, not humanity.

This is a recurring theme: there’s a conversation about “space exploration”, and after a bit you realize that half the people in the room are taking that to mean MANNED space exploration BY AMERICANS, with any other sort being at best a bit disreputable and at worst vaguely threatening.

Leif Erikson: I’m sorry, but it’s still a really dumb analogy.

One, the US space exploration budget is still about 60% higher, in real dollar terms, than it was in 1975. If our national will is flagging, you can’t see it from the numbers.

Two, the fact that the rest of the world is going into space is, and that its no longer a simple binary US/USSR competition… well, how is this a bad thing? India, China and Brazil are becoming rich enough to afford serious space programs, and they are choosing to spend some of their new wealth in space: why is this not a cause for celebration?

To imagine a future where Americans continue to dominate space exploration, you have to imagine a future where the rest of the world stays poor. Wouldn’t that be kind of a crappy future?

Three, Leif went for Leif himself and his immediate clan members and friends. Modern space exploration involves a worldwide community of scientists and space supporters. When Chandrasekhar discovered water on the Moon, were we supposed to sulk because it was a dirty Indian probe that did it? When the Japanese brought Hayabusa home, should we not have joined in that astonishing triumph of scientists and engineers over adversity? Should the 90+% of the world that’s not American ignore the glorious images from Cassini — and the accompanying avalanche of scientific information! — because Cassini is run by the imperialists of NASA?

Space exploration is science, you know? And science knows no borders.

Doug M.

When we get hit by the next asteroid (or if global climate change makes things unbearable and we perish first), our epitaph should read:

“Despite a demonstrated potential for greatness, this species, when it had an opportunity to push forward and explore ways to ensure its long-term survival, gave up power to a few who then gorged at the trough and undermined all by convincing them space exploration was too expensive.”

Can we retire the asteroid argument, please?

It’s already impossible for a dinosaur-killer asteroid to sneak up on us. We have the asteroid belt mapped pretty well; anything big enough to do that kind of damage, we would see coming decades if not centuries away.

At this point we can say with very very high confidence that there’s nothing bigger than a couple of hundred meters across that could possibly hit us within the next decade. We’re not perfectly safe yet — we could still be surprised by a rock in the ~50 meter range sneaking up on us — but at this point we’re talking impacts that might take out a city and give the rest of us spectacular sunsets for a few months, not dinosaur-killing world-enders.

And even that window is closing; within a decade we’ll have the inner Solar System mapped down to the little rocks too.

Enough with the asteroid strikes, please.

Doug M.

@Chris London: there may even be a ruthless self-selection mechanism for budding intelligences and civilizations; the ones that are either too aggressive or too complacent just don’t make it, they use up their local resources and/or they destroy themselves.

There is even some consolation in this. However, the major downside of this principle is the possible, even likely, situation in which higher intelligence and technological civilization are exceedingly rare. In that case we humans possess a very, very rare opportunity and responsibility to spread our life and intelligence.

Doug, very elliptical orbit objects might still take us by surprise.

Secondly, being able to detect is not yet being able to avert. A very large meteorite would still be very, very difficult for us to destroy or deflect. The sheer (nuclear) power required would be huge (hundreds to thousands of megatons TNT) and it would have to be delivered at the right spot and moment. This may appear to be quite a challenge for decades to come.

But I do agree that some other phenomena, such as supervolcanoes, pandemics, drastic climate change (ice age) and to a lesser extent still nuclear war, may pose more serious potential threats.

Most Earth-crossing asteroids *have* highly elliptical orbits. That’s why they’re Earth-crossing.

We’ve found most of them anyway. Why? Because an Earth-crossing asteroid can’t avoid coming within 1 AU of Earth at least once per decade. (Unless it’s in resonance with Earth, like Cruithne — in which case it simply can’t hit the Earth.) And current technology has very little difficulty seeing a 1 km object less than 1 AU away.

The only remotely plausible scenario would involve an Earth-crosser that avoided detection because it had been perturbed into a freakishly tilted orbit inclined way off the ecliptic. That’s not actually impossible. Earth-crossers are perturbed and abnormal almost by definition, and their orbits can go chaotic and strange. There are several known Earth-crossers with highly inclined orbits, most notably 2009 HC82, whose orbit is so inclined that it’s actually retrograde.

But these guys are rare — probably less than 5% of all Earth-crossers. And we’re detecting them anyway! Just more slowly. But every year, we cross a few more potential threats off the list. Within a generation we’ll have them all.

Doug M.

I whole-heartedly agree. While progress can never be fast enough for some, including myself, what has been accomplished in a mere 50 years of space flight is absolutely astonishing. And there is no doubt in my mind that the next 50 will be even more so.

Doug, what’s with the “reality check”? Sure we’ve spent more money, but we have gotten less in return. What did we get in return for all the money spent on the Lockheed X-33 Venture Star and its Aerospike engine? Do you realize that what you’re actually saying is that the “reality check” is that we’re pouring more of our future down the toilet?

Stunted: you’re right, there’s a huge amount of money wasted. To the example you give, I could add all the money wasted on the Soviet Moon-landing rockets and spacecraft, on Energiya and Buran, on the NERVA nuclear rocket programme, on the NASP, in Europe on Hermes, and I’m sure people could come up with many more examples. You might also want to add the waste involved in dismantling the Apollo Saturn system and indeed now the Space Shuttle instead of developing them further. And indeed the wasteful way the ISS was developed, when the US already had a perfectly functional station with Skylab.

We could quibble about whether there was more waste in the 1960s or more today. But surely the bottom line is that progress is happening. When the Chinese launch Tiangong there will be for the first time ever two functional space stations in orbit. Space Adventures is continuing to sell seats to private space travellers (inconceivable back in the 1960s and 1970s), and as Bigelow, SpaceX and others develop their systems this traffic can only grow. Meanwhile the use of unmanned satellites for comms, Earth observation and GPS has become absolutely integral to the economic infrastructure.

Yes, progress is slower than Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick imagined in 1968, but let’s not get impatient!

Stephen

Oxford, UK

Stunted & Astronist:

You could also take the stance that all of these cited programs were considerably less of a waste then the trillions spent on war, advertising, legal fees and other unproductive endeavors. At least with those programs technologies were developed and tested, to be one day perhaps dusted off and used as a starting point for something more successful. Or, equally useful, as an example of how not to proceed. Either way, lessons were learned, and that is worth something.

Frank asked: “Why doesn’t NASA build a “standard” planetary probe instead of re-inventing the wheel each time a new mission is created?”

Hmmm. A good idea, that has been tried at least once: the spacecraft was Mars Observer. Sadly, MO was lost because the “standard” fuel system (from earth-orbiting spacecraft of the time) turned out to be unsuited to a long cruise out to Mars, and malfunctioned.

Spacecraft have become substrates for software, and a lot of their software IS re-used. Even that has its perils, though. And don’t forget that many spacecraft, at least those operated by JPL, use common ground systems, cutting cost and increasing standardization. Also, CCSDS helped a LOT to standardize flight software and telemetry systems; see the Wikipedia entry on that. So a lot of standardization has occurred (shared parts, shared software, shared telemetry systems) but much of it isn’t visually apparent.

Regarding the view if it isn’t an American space mission then it isn’t good enough or worth covering, etc., the Japanese recently flew a solar sail craft past Venus. It even took a photograph of itself and the planet in the background. That should have been front-page news, but it wasn’t. I only learned about it from a space blog almost two months after it happened and I try to keep up on these things. The Japanese also retrieved a capsule containing particles from an asteroid thanks to a probe they built and operated which landed on the space rock. The robot explorer itself went through all kinds of trials that threatened to end its mission at any point. This one got a bit more attention but has since faded from the public attention.

The Russians will soon be sending a probe to land on Phobos and return samples of it to Earth. The Chinese recently sent another orbiter to the Moon but you might be forgiven for barely knowing about that.

Voyager was not an end. There probably won’t be another major flyby mission like it any time soon, but that is in large part because what those two probes did allowed scientists and space agencies to focus on specific worlds, as was the point of the Grand Tour. Space exploration is going a bit slower than what we were promised in the early days, but it will happen – it just might not happen the way we planned or with the organizations we assumed would do them.

Voyager 2 to Switch to Backup Thruster Set

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.cfm?release=2011-341

November 05, 2011

Voyager Mission Status Report

NASA’s Deep Space Network personnel sent commands to the Voyager 2 spacecraft Nov. 4 to switch to the backup set of thrusters that controls the roll of the spacecraft. Confirmation was received today that the spacecraft accepted the commands. The change will allow the 34-year-old spacecraft to reduce the amount of power it requires to operate and use previously unused thrusters as it continues its journey toward interstellar space, beyond our solar system.

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are each equipped with six sets, or pairs, of thrusters to control their movement. These include three pairs of primary thrusters and three backup, or redundant, pairs. Voyager 2 is currently using the two pairs of backup thrusters that control the pitch and yaw motion of the spacecraft. Switching to the backup thruster pair that controls roll motion will allow engineers to turn off the heater that keeps the fuel line to the primary thruster warm. This will save about 12 watts of power. The spacecraft’s power supply now provides about 270 watts of electricity. By reducing its power usage, the spacecraft can continue to operate for another decade even as its available power continues to decline.

The thrusters involved in this switch have fired more than 318,000 times. The backup pair has not been used in flight. Voyager 1 changed to the backup for this same component after 353,000 pulses in 2004 and is now using all three sets of its backup thrusters.

Voyager 2 will relay the results of the switch back to Earth on Nov. 13. The signal will arrive on Earth on Nov. 14. Voyager 2 is currently located about 9 billion miles (14 billion kilometers) from Earth in the “heliosheath” — the outermost layer of the heliosphere where the solar wind, which streams out from the sun, is slowed by the pressure of interstellar gas.

The Voyagers were built by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., which continues to operate both spacecraft. JPL is a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate. For more information about the Voyager spacecraft, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/voyager .

Rosemary Sullivant 818-354-0880

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

Rosemary.sullivant@jpl.nasa.gov

2011-341

A 1993 paper on the music of the Voyager Interstellar Record by several music experts:

http://music.dartmouth.edu/~larry/published_articles/voyager_.pdf

December 20, 2011

Carl Sagan and “The Sounds of Earth”

If, billions of years from now, extraterrestrials were to come across one of our far-flung interstellar space probes, what could they learn of us? In the 1970s, as NASA prepared to send its first probes beyond the distant reaches of the solar system, this was the question that worried renowned scientist and author Carl Sagan.

Sagan, who died 15 years ago on this day, was enormously influential in a number of ways—he was a prolific researcher and publisher of articles on planetary science, and his books and popular PBS series Cosmos inspired a generation with the remarkable discoveries of astronomy and astrophysics. But his most long-lasting and significant impact might indeed be the time capsule he placed on the NASA probes: a gold-plated record titled “The Sounds of Earth.”

“From the beginning, Sagan was a strong believer in the probability that there is intelligent life out there,” says Jim Zimbelman, a geologist at the Air and Space Museum, which holds a replica of the gold record in its collection. “And because of that, he said, ‘Look, these are the first man-made objects to leave the solar system. What if someone finds them?’”

Full article here:

http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/aroundthemall/2011/12/carl-sagan-and-the-sounds-of-earth/

The Voyagers: A Short Film About How Carl Sagan Fell in Love

by Maria Popova

A thousand billion years of love, or what the vastness of space has to do with eternal mixtapes.

In 1977, NASA launched two unmanned missions into space, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. Though originally intended to study Saturn and Jupiter over the course of two years, the probes have long outlasted and outtraveled their purpose and destination, on course to exit the solar system this month.

Attached to each Voyager is a gold-plated record, known as The Golden Record — an epic compilation of images and sounds from Earth encrypted into binary code, the ultimate mixtape of humanity. Engineers predict it will last a billion years.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Golden Record was conceived by the great Carl Sagan and was inspired by his childhood visit to the 1939 New York World’s Fair, where he witnessed the famous burial of the Westinghouse time capsule. And while its story is fairly well-known, few realize it’s actually a most magical love story — the story of Carl Sagan and Annie Druyan, the creative director on the Golden Record project, with whom Sagan spent the rest of his life.

Voyagers is a beautiful short film by video artist and filmmaker Penny Lane, made of remixed public domain footage — a living testament to the creative capacity of remix culture — using the story of the legendary interstellar journey and the Golden Record to tell a bigger, beautiful story about love and the gift of chance.

Lane takes the Golden Record, “a Valentine dedicated to the tiny chance that in some distant time and place we might make contact,” and translates it into a Valentine to her own “fellow traveler,” all the while paying profound homage to Sagan’s spirit and legacy.

“Carl and I knew we were the beneficiaries of chance, that pure chance could be so kind that we could find one another in the vastness of space and the immensity of time. We knew that every moment should be cherished as the precious and unlikely coincidence that it was.” ~ Annie Druyan

And as I launch into a voyage of chance of my own this week, I lose myself in the poetry of Lane’s closing words:

“It’s hard to imagine the Golden Record being made now. I wish Carl Sagan were here to say, ‘You know what? A thousand billion years is a really long time. Nobody can know what will happen. Why not try? Why not reach for something amazing?’ There is no way to forestall what can’t be fathomed, no way to guess what hurts we’re trying to protect ourselves from. We have to know in order to love, we have to risk everything, we have to open ourselves up to contact — even with the possibility of disaster.”

Full article and complete film online here:

http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2011/12/27/the-voyagers-penny-lane-carl-sagan/