Remember Arthur C. Clarke’s “The Wind from the Sun”? The short story, telling of a race from the Earth to the Moon via solar sail, appeared in 1964, portraying the vessel Diana and its 50 million square foot sail, all linked to its command capsule by a hundred miles of cable. In those days, the sail idea was newly minted and more or less the domain of science fiction buffs, who had first encountered it in Carl Wiley’s “Clipper Ships of Space,” a non-fiction article written under a nom de plume for Astounding Science Fiction in 1951. The 1960s would see tales like Poul Anderson’s “Sunjammer” and Cordwainer Smith’s haunting “The Lady Who Sailed the Soul.”

Addendum: When I say the idea was ‘newly minted’ (above), I’m referring to the engineering ideas that could go into an actual mission. The idea of solar sailing itself goes back much further — see my Centauri Dreams book for the whole backstory.

Wiley’s sail concept was startlingly ambitious for its time, an 80-kilometer design that preceded the first scientific paper on solar sails by seven years. But science fiction would go on to bring even larger sails to spectacular imaginative life. Thus Clarke:

All the canvas of all the tea clippers that had once raced like clouds across the China seas, sewn into one gigantic sheet, could not match the single sail that Diana had spread beneath the Sun. Yet it was little more substantial than a soap bubble; that two square miles of aluminized plastic was only a few millionths of an inch thick.”

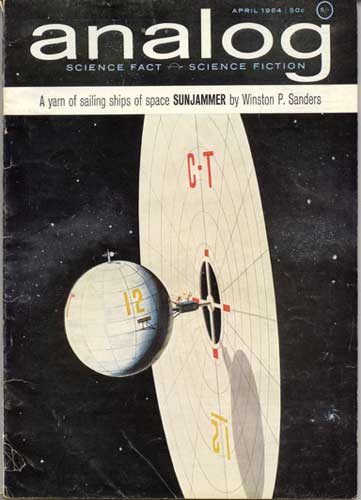

Image: Poul Anderson, writing as Winston P. Sanders, published “Sunjammer” in Analog‘s April, 1964 issue.

Cordwainer Smith (Paul Linebarger) wrote of the “tissue-metal wings with which the bodies of people finally fluttered out among the stars.” That story, from the April, 1960 issue of Galaxy, described ‘the age of sailors’:

The thousands of photo-reconnaissance and measuring missiles had begun to come back with their harvest from the stars. Planet after planet swam into the ken of mankind. The new worlds became known as the interstellar search missiles brought back photographs, samples of atmosphere, measurements of gravity, cloud coverage, chemical make-up and the like. Of the very numerous missiles which returned from their two? or three-hundred-year voyages, three brought back reports of New Earth, an earth so much like Terra itself that it could be settled.

The first sailors had gone out almost a hundred years before. They had started with small sails not over two thousand miles square. Gradually the size of the sails increased…

Entering the Age of Sail

We’re a long way from the era of giant sails of the sort that these writers, and soon scientists like Robert Forward, would depict in their work. But reading through a recent article on solar sails in Nature brought these memories back because solar sails and their beamed-propulsion cousins, so-called ‘lightsails,’ have been at the forefront of interstellar research ever since those days. Today’s IKAROS and NanoSail-D experiments, soon to be joined, we hope, by LightSail-1, are the beginning. However long it has taken — and there was serious consideration about a NASA sail to Halley’s Comet well over thirty years ago — we’re at least getting sails into space.

Japan’s IKAROS sail has just seen its mission extended until March of 2012. The first sail to make it into interplanetary space, IKAROS was a payload that would have reached Venus for its flyby with or without sail power, but that’s not the point. The idea was to shake out new technologies, and IKAROS did demonstrate acceleration from solar photons on its way to Venus, as well as giving controllers the chance to put its attitude control system to the test. The key result was to bulk up our data about sail technology so that engineers can build better ones in the future.

And while NanoSail-D continues its flight, an attractive catch for space-minded photographers when conditions are right, its low-Earth orbit will soon cause atmospheric drag to bring it down, a fiery re-entry that will tell us about using such technologies to de-orbit decommissioned satellites. While IKAROS is a 200 square-meter sail, NanoSail-D is much smaller, but principal investigator Dean Alhorn is now designing FeatherSail, an attempt to go beyond low-Earth orbit with a sail that will measure 870 square meters. And as we’ve discussed in these pages before, JAXA aims to build a much larger sail for a Jupiter mission launched at the end of the decade.

A Toast to Old Ideas

Sometimes I like to look through abandoned mission concepts, out of curiosity and the frisson that comes from watching new and speculative ideas encounter the combative world of engineering and politics. I’ve already mentioned the NASA sail studies for Halley’s Comet, which were led by one of today’s leading sail proponents, Louis Friedman. Then there was the TAU (Thousand Astronomical Unit) mission, designed to push deep into the Kuiper Belt as a platform for astrophysics and astronomy. First conceived around nuclear-electric propulsion systems, TAU was also examined in terms of solar sailing, using a close solar pass to achieve the needed acceleration. No final choices were made for this mission that never flew.

The Nature article referenced above notes one other abandoned sail concept, a solar sail satellite situated over the Moon’s south pole for use as a communications relay to a lunar base. The Constellation program, designed around future missions to the Moon, was considering such a sail before the program was canceled in February of 2010.

But stay optimistic, because with IKAROS and NanoSail-D already in space, we’re only getting started. “There’s a niche for solar sails and it’s there for the taking,” JPL’s John West says in the article, and the advantages of leaving the propellant behind should soon become apparent as we unfurl still more sails in space. Sometimes abandoned missions are harbingers of the more realistic attempts that succeed.

I can’t see how solar sailing can ever be more than a niche mode of propulsion withing the solar system, suitable for payloads that can tolerate slow transit times. This might make them suitable for instrument carrying and possibly bulk material haulage. Rocket propulsion, especially using solar energy and readily available volatile resources like water will be much more suitable for most transport, and especially humans.

If there were to be a good role for large, reflecting surfaces, I think it would be for concentrating solar energy. This would enhance the effectiveness of solar PV and allow its use in the outer solar system. “Sails” with a parachute like surface and solar arrays at the focus might make more sense for space transportation.

Paul, I am new to your blog so forgive my ignorance. Has anyone postulated this concept:

As our solar system fills up with solar sails, collectors and reflectors we create what I believe is Dyson’s original concept of his sphere. These reflectors can collimate a beam of light to a nearby star, a light bridge allowing solar-sailed habitats to colonize it.

Has anyone thought of looking for such a bridge as an indication of intelligent life out there?

My understanding (wrong?) is that “sundiver” solar sails that pass close to the sun (possibly in multiple orbits) could attain very high speeds, enough for missions past the heliopause to nearby interstellar space to only take a few years. Given the ~30 years that an ion-powered probe would take to make the same trip it’s an idea worth pursuing.

NS, the fastest figure I’ve seen for a ‘Sundiver’ mission to the outer system is on the order of 500 kilometers per second (this via Geoffrey Landis). And you’re right, that’s quite fast compared to Voyager’s 17 km/s. The TAU studies ruled out all propulsion concepts save solar sail and ion methods.

Hi Paul

A few years ago there was a discussion of message cairns as a more effective means of sending out data to other intelligences, rather than isotropic beacons. Rose & Wright were the two investigators and at the time they suggested ion-drive rockets to carry the messages at ~150 km/s or so. I contacted them and suggested solar or magnetic sails, both of which could hit ~300-600 km/s and, quite possibly, be able to deccelerate the message probe at destination. Since then Matloff’s beryllium balloon sail concept has been published and it demonstrates, at least to me, the relative ease of achieving such speeds to propel passive long-term “probes”. The energy cost of such cairns effectively drops to just that for manufacturing and launch. Transport is “free”. Isotropic beacons seem excessively wasteful by comparison.

I do wonder then at what a cairn might look like after travelling between the stars for millennia. Would we recognize it once it has achieved a solar orbit? And where would such things accumulate naturally? What medium would retain data-integrity for millennia? I think the arrival of solar-sails of our own should prompt a new round of SETA efforts to identify exosolar messages-in-bottles.

I must admit to being puzzled over the excitement accompanying the solar sail concept – to me it always looked like an interim measure. And I don’t just mean against super advanced transport technologies such as Space Elevators. Such traditional mechanisms as cycling transporters between planets, and utilizing gravitational assist seems sufficient to confine the solar sail to a niche market within the inner solar system. It would not make sense to combine these two types of transport since then we can forget about adjusting these cyclers trajectories with aeroassisted maneuvers, particularly those using wave rider forms.

I admit that one such niche – having geostationary communications satellites that were not perfectly on the equator seems truly ingenious, but surely communications satellites are on their way out anyway.

As for the prospects for sail assisted interstellar probes this looks even worse to me – with the only interest being that if we had less than a decade to complete the task of sending one, that is quite possibly how we would do it. Of cause those probes would be overtaken by more advanced ones that we sent later well before they reached their destinations.

Actually the whole concept of the solar sail is so beautiful that I hope they find much use but I see scant evidence for such glory.

Adam writes:

I remember the paper you’re talking about, Adam, and the discussion of it here. Fascinating idea. The issues you’re sketching out here would make for an interesting science fiction story, and they also are issues we need to look at in our own human terms. What kind of medium for long-term data storage? That one really resonates given how quickly modern media deteriorate.

Rob Henry writes:

I’m more bullish on sails than you are, Rob, especially since beamed sailed concepts — anything from microwave to laser to magsails — may wind up offering our best choice for getting up to, say, 10 percent of lightspeed. There are many alternatives, but we don’t know how they’ll pan out, so I wouldn’t rule out sails as a major possibility for early interstellar probes. These would not, of course, be conventional solar sails but ‘lightsails’ and the infrastructure behind them would be huge. We’ll have to see whether other methods come in at significantly lower cost as we learn how to make them effective.

The thing I like about solar sails is that the concept agrees with the old engineering dictum of simplicate and remove weight. The more simple and straightforward a concept is, the less that can go wrong. When you talk about huge energies propelling starships, the immediate reaction is that huge energies can go hugely wrong, gentle energies can only go gently wrong. The possibility of a catastrophic explosion on a sailcraft is nil.

All we need now is to have someone attach a few sticks of dynamite or whatever equivalent works in the vacuum of space to disprove this. ;-)

Paul is right if sundrive could accelerate to 500 kps then we need a laser that can acclerate the sail 60 times faster.

I am assuming the probe is in the straucture of the sail itself and is very light.

What we need is better nanotechnology and a big laser . It is the most viable way to launch something in the next 50-100 years.

Sundriver would pass voyager and a laser sail would pass them all. Should we have not sent out voyager and pioneer?

I believe light sails are a remote option for near-relativistic travel, because of the corrosive effect of the interstellar medium. Lightsails are by nature very thin, and would have no resistance whatsoever to energetic particles.

For slower travel, sun-diver sails are an interesting idea, but I expect that the velocities mentioned here will turn out hopelessly optimistic in the face of practical obstacles. We are talking about getting REALLY close to the sun, here.

One could argue that being gently marooned in space is no better than going out with a bang…

Sunlight cannot be collimated with mirrors to anywhere near the degree that would be needed. A really large laser would be required to do this.

Somehow this all reminded me of Chandlers – Rim of Space-Stories from the 70s – the sunjammers

Some comments here which are more critical to the idea dont think ahead.

Inbound from outer planets – solar sails wont be that of much help. But when using them outbound and use H or H³ for propulsion from jovian planets to return inbound again? Letting the sail out there, for further use or different purposes.

More, for unmanned space probes to the near systems around us, it may be a rather cheap method to provide the initial speed/velocity and if too far away from the sun, jettison the sail and then use a different method to proceed further.

And agreeing on some of the limitations of sails, it still comes to me as the single cheap and rather low tech/low investment version of bulk carrier from inner to outer planets

Addendum to my February 6, 2011 at 17:26

We nearly allways are thinking about getting max. velocity when it comes to unmanned AND manned space probes to other systems. Until now, I never read of constant speed vehicles. If speed is constant and rather low, we could use sail operated fuel ships going earlier and ahead of everthing else to act as fuel stations on the way.

Of course, this increases flight time by much, but think of the ratio between fuel mass and operational mass of the probe. More, when there is no high speed in the midth of flight, any shielding against atomar and bigger debris on the way, does become much less as a problem.

I wonder if there might be a middle ground between a sail propelled purely by solar light, and laser propulsion? Wiki mentions that zone plates can be used to further focus laser energy on the sail; might it be possible to place several such plates in a low solar orbit, where they can focus solar light on the sail from a point that sees more light intensity, thus acheiving better thrust without the need for a powered laser?

Although saddled with a 0.1% lightspeed limitation, one advantage a solar sail has on the alternatives (when used for interstellar travel) is that it can put the brakes on at journey’s end and presumably reach some form of orbit (assuming the star at the other end has a similar output to our own Sun, or we use some other trickery to achieve the same).

Using lasers to add yet more oomph for a 1-2% lightspeed seems wonderful at first glance, but does imply a flyby mission – there won’t be a second laser at the other side, and aerobraking at such a fair clip might be a tad challenging.

On another note, I like the idea of lightsails being used within our own solar system as a method for relocating the resources that would be needed to assemble a spacecraft capable of achieving that magical 10% lightspeed target *and* decelerating at the destination.

The truly nice part of a solar sail is no need for fuel. Just that open’s up probes with indefinite life span’s. Meaning loitering at one area of interest then moving, albeit slowly, to another. Or just enabling communication relay’s for the inner solar system.

Obviously reflected light is a more efficient use of solar energy than lasers. Equally obviously there are such extreme focusing problems that reflected light could only be used out to a few times the diameter of the Dyson sphere in Mark Presco’s idea. Also it would not make any sense to try to focus such a beam on one sail ship. Thus at first I thought that his plan was unworkable under any circumstances, then I thought of an exotic (ie not native) stage II civilisation around an O or B star. The entire population would want to leave relative quickly and preferably together in a grand fleet (to another O or B star) a few thousand years before the supernova.

Of cause, such a setup would not allow for particularly fast travel – but who are we to judge the mindset of aliens. Actually, because this travelling population would be so massive, it would get around most psychological problems associated with generationship travel.

Sundiver sails are a good bet, but I think a 500 km/s sail will have to be an engineering miracle. One must plunge to within a thousandth of an AU, ie lesto ~ a million km, where it is hot indeed. The sail can use desorption for a rocket effect, which we (brother Jim & self) included. Let me quote from a paper a decade or so ago:

As a simple example, consider a sail falling sunward on a parabolic orbit. It will be accelerated by

(a) the ?V imparted by desorption at perihelion

(b) ordinary solar sail acceleration on the outward-bound leg, once the desorbed layer is gone, leaving a reflecting sail

We can find an approximate expression for the final velocity VF

with respect to the sun, following energy analysis, as in Matloff’s Deep Space Probes (2001). The sail’s parabolic velocity at distance R is

V’ = 1.4 (GM/R)1/2 = 93 km/s (R/0.1 AU)-1/2

At perihelion of 0.1 A.U. the sail reaches a temperature (for seemingly plausible values of absorption and emissivity)

T = 927 K [(?/0.3)(?/0.5)-1]1/4 (R/0.1 AU)-1/2

For such temperatures a considerable ?V > km/s is plausible for a range of desorption materials. Losing its mass load at perihelion, the sail thereafter works as an ordinary solar sail, attaining a final exit speed from the solar system

VF = 19.5 km/s [(?V/2 km/s) + (3?’)-1 ]1/2

= 3.9 AU/year (?V/2 km/s)1/2 [1 + 0.33 /(?V/2 km/s)(?’)]1/2

Here ?’ is the sail areal mass density in units of 100 gm/m2. In the brackets, the first term comes from acceleration (a), the ?V imparted by desorption at perihelion and the second from (b), ordinary solar photon acceleration on the outward-bound leg, once the desorped layer is gone, leaving a reflecting sail.

The sail’s speed as it passes through the outer planets will exceed VF. The linear sum of ?V and the ordinary solar sailing momentum in the square root above means there will be a simple tradeoff in missions between the two effects, which are equal when the last term in brackets above is unity.

This is only a rough calculation, omitting many mission details, such as sail maneuvering near the sun. I have assumed a perfectly reflecting sail on the outward leg, and that desorption would occur quickly at perihelion.

++++++

I’d like to see Geoff Landis’s calculations, too.

Rob Henry has come close to the concept I had in mind. I believe the future of the human race is in zero-G habitats. There is plenty of room out there and we can essentially fly within them. If these habitats orbit the sun at approximately 1 au, solar energy can sustain the habitat with current technology, just as it does on earth. No radical technological breakthroughs are required.

If we can create a light bridge with a solar flux density equivalent to that at 1 au, we have the technology for interstellar travel. By my calculations that’s only one billionth of the total output of the sun.

For multigenerational zero-G habitats, it makes little difference to the inhabitants whether you’re spinning your wheels orbiting the sun, or on your way to the next star. And we don’t need a planet to colonize. We just orbit that star and begin building a bridge to the next star.

The beauty of this plan is that we have, or are close to having the necessary technology. The chink in the plan is the human politics required to sustain the bridge for the length of time required. All bets are off we invent warp drive or some other advanced technology.

Gregory Benford, I understand the utility of the desorption process, but I do not see how it exceeds normal chemical potentials. Why wouldn’t it be more effective to coat these sails with some high-energy uv-triggered explosively-decomposing chemical. And wouldn’t such a chemical absorb the suns heat anyway?

If the problem is preserving the structural integrity of the sail, why not alternate thin layers of deabsorption material with layers of high energy chemicals?

Oh, I have just realised that if the idea was to combine rocket and sundiver, a much more efficient rocket would have been attached to the body of the payload. The idea of this procedure must have been to protect the sail and so minimise the potential perihelion, while reducing the delta V cost for that protection. Oops

With regards to the sun diver that Gregory benford mentions, does the extra material that provides the desorption mass create a sufficiently strong sail sheet to allow the sail to be unfurled, whilst leaving a much thinner sail sheet at the end of the desorption phase than could otherwise be deployed?

Jules Verne predicted solar sailing in 1865:

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2011/02/pictures/110208-jules-verne-google-doodle-183rd-birthday-anniversary/#/jules-verne-inventions-solar-sail-light-propulsion_32044_600x450.jpg

The point my brother Greg is making, which is lost in the equations, is that a sail approaching the sun close enough to escape the solar system with 500 km/sec would be heated to temperatures sufficient to evaporate the sail material and fry any electronics.

The paper of ours that he’s referring to is: “Desorption Assisted Sun Diver Missions”, Gregory Benford and James Benford, Proc. Space Technology and Applications International Forum (STAIF-2002), Space Exploration Technology Conf, AIP Conf. Proc. 608, ISBN 0-7354-0052-0, pg. 462, (2002).

I should add with regard to Geoff Landis’ calculations that all this was a genuinely back of the envelope result — i.e., a real envelope, and quick figuring with a ballpoint pen. We were in his office at GRC in 2003 and I had been asking about Sun-diver missions — I doubt there would be any disagreement with Greg’s conclusions from him at this point.

It might not be completely relevant to this discussion, but has anyone thought of what speeds are attainable with a spaceprobe or spaceship slingshooting past a very heavy body in a multiple star system (gravity assist)? In the center of the Milky Way, there is a big star in orbit around a black hole, and the orbital speed is something like 5000 km/sec. (They have named the start ‘S2’, try http://www.eso.org/public/news/eso0226/) . That’s more than 1% of the speed of light.

A chance of a lifetime: the missions to Comet Halley

Twenty-five years ago today the Giotto spacecraft flew past the nucleus of Comet Halley, part of an international armada of spacecraft sent to study the comet. Andrew LePage examines the Soviet, Japanese, and European spacecraft sent on a one-in-a-lifetime mission.

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1798/1