Space writer Keith Cooper, the editor of the UK’s Astronomy Now, is currently attending the Royal Astronomical Society’s meeting in Llandudno, Wales — in fact, the photo of him just below was taken the other day in Llandudno. But the frantic round of presentations hasn’t slowed Keith down. When last spotted in these pages, he was engaged in a dialogue with me about SETI issues. That exchange got me thinking about having Keith talk to Michael Michaud, considering their common interests and realizing that they had already met at last year’s Royal Society meeting where so many of these issues were discussed. Michael was kind enough to agree, and what follows is an exchange of views that enriches the SETI debate.

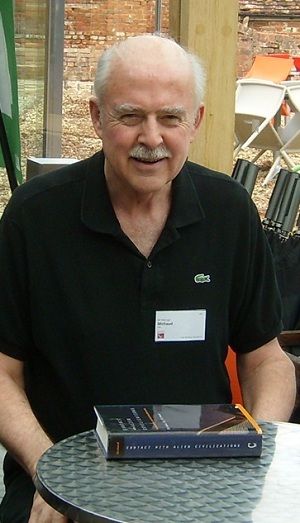

Centauri Dreams readers know Michael Michaud to be the author of the essential Contact with Alien Civilizations: Our Hopes and Fears about Encountering Extraterrestrials (Springer, 2006), but he’s also the author of over one hundred published works, many of them on space exploration and SETI. Michaud was a U.S. Foreign Service Officer for 32 years before turning full-time to research and writing. He had a wide variety of assignments during his diplomatic career, including Counselor for Science, Technology and Environment at the U.S. embassies in Paris and Tokyo, and Director of the State Department’s Office of Advanced Technology.

Michael was directly involved in the negotiation of international science and technology cooperation agreements, represented the Department of State in interagency space policy discussions, and testified before Congressional committees on space-related issues. It’s particularly germane to mention that he was actively involved in international discussions on contact issues within the International Academy of Astronautics for more than twenty years, and was the principal author of the so-called First SETI Protocol (actually entitled ‘Declaration of Principles Concerning Activities Following the Detection of Extraterrestrial Intelligence’). His recent work has focused on the importance of bringing more historians and other social scientists into debates about the possible consequences of contact.

- Keith Cooper

A few years ago I interviewed Andy Sawyer, the chief librarian and administrator of the Science Fiction Foundation at the University of Liverpool, and asked him about our predilection for alien invasion stories. “Because alien invasion stories are cool, and there are all sorts of anxieties that can be set in an invasion story,” he said. And I agree – I enjoy watching the latest alien invasion movie as much as the next person. But for many people their only exposure to ‘aliens’ is through the lazy stereotypes of Hollywood flicks, or perhaps the mono-cultural depictions in Star Trek, and this is driving how they envision real alien civilisations to be. Michael, in your work raising awareness of the consequences of METI you’ve helped bring home the fact that our ideas about aliens are just too simplistic, and consequently our visions of contact are equally superficial.

At the Royal Society last October you spoke of binary stereotypes – the wise old aliens happy to pass on their knowledge to us and teach us to become better beings, and the nasty, snarling conquerors hell-bent on wiping us off the face of the planet and stealing all our women and water (as the B-movie SF tropes usually go). What seems a shame is that some scientists in the SETI community have slipped into taking the first of these stereotypes for granted; the notion of an Encyclopedia Galactica is wholly expected by many, but this requires an enormous act of altruism on behalf of the sender.

I’ve seen lots of arguments suggesting that advanced extraterrestrials will inevitably be altruistic, yet it seems to me to be mainly the astronomers, speaking outside of their field of expertise, who are advocating such optimistic assumptions (without even defining what they mean by altruism – kin, or nepotistic altruism, is very different from reciprocal altruism, which is probably what they are referring to). Whenever I speak to evolutionary biologists, anthropologists, philosophers and other social scientists – people whose job it is to study social behaviour – they are much more cautious. For instance Professor Jerome Barkow, a sociocultural anthropologist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, described to me one possible example of “a fear-filled species, hypersensitive to danger, who have evolved intelligence selected for fear because it was the only way they could manage to win in competition against related species.”

Such a fearful species may constantly be on the lookout for danger, and in the worst case scenario may even be xenophobic. Simon Conway Morris, a paleontologist at the University of Cambridge who champions the idea of convergent evolution, is even more blunt: “If intelligent aliens call, don’t pick up the phone!” Meanwhile, Professor Nick Bostrom, Director of the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, told me that “even if we could detect a pattern of increasing moral enlightenment in human history, it would be hazardous to extrapolate from that into our future, but I imagine that is what would underpin some people’s optimism about technologically advanced civilisations. As for altruism, we just have no idea about that.”

There are so many questions I would like to ask. My main question to you Michael is why are we not listening to those with the knowledge base of human behaviour who are best-placed to make judgments about the possible actions of extraterrestrials? Does SETI run the risk of becoming too exclusive? How can we expand the discussion to include people from all disciplines all around the globe? Furthermore, at the Royal Society, you said that it was time to make the most objective analysis that we can of the benefits and risks of METI. How do we escape the cliche of invasion to investigate the subtler pros and cons of contact?

- Michael Michaud

Keith, I agree with much of what you say. Escaping the stereotypes that bedevil discussions about contact with ETI will not be easy. Because we have no confirmed information about the nature or behavior of extraterrestrial intelligence, our speculations about contact rest on belief, preference, or analogies with ourselves. Many people are impatient with the resulting ambiguity and want binary, either-or answers.

Early SETI advocates promoted the image of aliens as altruistic philosopher-kings not only because of personal preference, but also because they were trying to gain public support for a highly speculative endeavor. An idealistic and hopeful vision was a better sales pitch. For SETI advocates, that became the default position in discussions about the consequences of contact. Media treatments of contact issues, including documentaries, also are driven by what producers think will sell. Alien invasions — or wise, harmless extraterrestrials — overpower sober analyses based on what we know of human behavior. My responses to questions from three companies producing TV shows on the alien invasion theme were politely rejected not because they were wrong, but because they were less exciting than a war game.

Historians and other social scientists could offer more grounded visions of contact based on their studies of the only technological intelligent species we know – ourselves. For example, the human experience suggests that civilizations are not by nature either hostile or peaceful; their actions depend on the circumstances of the moment. Unfortunately, there is very little research funding or career reward for doing such work.

Many physical and biological scientists are not listening because they are skeptical of social science findings. Papers on social science issues such as the consequences of contact were pushed into the last hour of the last day of the June 2010 Astrobiology Conference. Yet some physical and biological scientists make sweeping statements about the behavior of intelligent beings that are not empirically grounded in the human experience. Imagine the reaction if a group of social scientists published conclusions about physical or biological processes without confirmed evidence.

How can we expand the dialogue about the consequences of contact? One starting point might be for a worthy organization interested in policy or social science issues to invite physical, biological, and social scientists to a themed conference on the benefits and risks of contact, including examples from human history. The Royal Society has set a useful precedent. I have some additional thoughts on this issue, but will hold them until I have your response.

- Keith Cooper

Michael, I’m intrigued by your comment that a hopeful and optimistic vision of contact has been adopted because it makes a better sales pitch. It strongly echoes something that James Benford commented on following my previous SETI dialogue with Paul, namely the claim that Arecibo could detect a signal from another Arecibo 500 light years away is a myth perpetuated as part of SETI’s sales pitch.

[PG comment: Excuse me for interjecting, but I want to add that Benford has added material on the Arecibo signal in a revised edition of his paper “Costs and Difficulties of Large-Scale ‘Messaging’, and the Need for International Debate on Potential Risks,” written with John Billingham. This latest version is not the one currently up on the arXiv server, so let me quote from what Benford says:

A similar argument quantifies the ‘Arecibo Myth’, i.e., that that Arecibo (Earth’s largest radio telescope) would be able to detect its hypothetical twin across the Galaxy (Shuch, 1996). Arecibo can’t realistically communicate with another Arecibo over such distances. Those who so claim do not state their assumption that the bandwidth will be extremely narrow (0.01 Hz), that both the receiver and the transmitter will stare exactly at the right very small part of the sky, tracking each other and that the receiver will track for hours in order to integrate a very weak signal and that no information will be sent. This last point is that, because the bandwidth is so small, the bit rate is glacial, far less than the slowest modem, maybe a bit per hour in the best case.

Sorry for the interruption, and now back to Keith].

Of course we want the public, and those who would finance SETI, to feel hopeful about the possibility of contact. The detection of a message from another intelligent civilisation would be profound in ways that we are only beginning to perceive, both scientifically and culturally, and we can only explore those consequences with the aid of social science. Despite having an astronomical background, I do find the social science aspects of contact equally as fascinating as the physical science of the search itself. I’ve learnt so much more about the human experience through my reading as I try to understand the nature of contact than I otherwise would have. SETI is a rare merging of the physical and social sciences and is all the richer for it – those that push cultural and sociological debates on contact to the end of conferences, to footnotes in papers and wave them away in vague, sweeping gestures on alien altruism do SETI a great disservice.

The social sciences do not necessarily come down against METI and the hope for peaceful and rewarding contact – there are compelling arguments both for and against (as an example of the former, I’d cite Professor Steven Pinker of Harvard University championing the ‘myth of violence’ and the notion that we are becoming more peaceful as we become culturally and technologically more advanced – see his TED talk on the subject – the idea is that we could use this as a template for alien civilisations). What the social sciences do show is that the consequences of contact are more complex than the threat of invasion or dreams of uplift by wise philosopher kings.

This dialogue is about alien motivations; fear seems to be a standout candidate, as Jerome Barkow alluded to. Adrian Kent at the Perimeter Institute has taken this to extremes to explain the Fermi Paradox in his recent paper ‘Too Damned Quiet.’ Here he argues the Galaxy is quiet because natural selection chooses civilisations that remain inconspicuous in the face of galactic predators. He writes:

“Advertising our existence in such an environment would be risky: a predator species might decide it could afford to predate on us, and even a reticent neighbour species might decide it could not afford to leave us attracting the attention of predators to the neighbourhood.”

While Kent’s fear-filled, predator-dominated Galaxy is at the extreme end of possible contact scenarios, it is something to be aware of. So too are the more subtle aspects that are often dismissed in the face of sensational stories of alien invasion. But we have to be able to discuss all the possibilities without fear of prejudice. No one can say what alien motivations will be, and I’m not trying to argue for any particular viewpoint other than all possibilities are currently fair game.

SETI’s current sales pitch seems to be holding back the wider debate. We have both commented on the often abysmal reporting of the consequences of contact in the media. I’d like to begin to change this, here and now. We need a new sales pitch. Through SETI we’re trying to find our place in a Universe that could be equally full of exquisite wonders and terrifying dangers, and everything in between. If we cannot guarantee a vision of contact that is as idealistic as the one that went before, then Michael what should our new message be?

- Michael Michaud

So, where do we go from here? First, it is time to free ourselves of the binary stereotypes that Hollywood, the Cold War, and the political reaction to it have imposed on us. We should be wary of both utopian and apocalyptic predictions of what contact might bring. We have no basis for assuming that other technological civilizations would welcome contact with us, nor do we have any basis for assuming that they would be hostile.

Second, it is time to fill in the middle ground between the extremes of a helpful altruistic message and an alien invasion. There are lots of other potential scenarios of contact, many of which have appeared in science fiction. For example, what if we detect a one-time alien signal not meant for us and are unable to find it again? What if that signal is nothing more than a dial tone? That would be contact without either communication or danger.

What if we find evidence of astroengineering on a scale far beyond our own abilities? That would imply a civilization so technologically powerful that it might consider us irrelevant, if it even noticed our existence. (In Arthur Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama, a giant alien space craft using our sun for a gravitational assist passes through our solar system without stopping, or communicating.) What if we find an alien probe in our solar system that is doing nothing we can detect – no messages, no firing of weapons, not even a friendly glow? Such a probe might have been another civilization’s response to detecting signs of biochemistry in earth’s spectrum a billion years ago. (Would they be looking for the same kinds of evidence we seek? If not, they might miss Earth life.)

There are hopeful signs. Recent frictions among those interested in this issue may reflect a broadening and maturing of the debate. While some astronomers still dismiss the possibility of interstellar flight even by uninhabited machines, Seth Shostak of the SETI Institute has recognized in print that we humans could launch robotic interstellar probes by the end of this century. That puts the possibility of direct contact back on the agenda. No Star Trek aliens would walk down the ramp; we would be dealing with smart machines.

Third, those of us active in this field should evaluate the implications of alternate scenarios of contact as best we can. One starting point might be the Rio Scale proposed eleven years ago by Ivan Almar and Jill Tarter.

Fourth, we need to get more high-profile figures from the social sciences to speak or publish on this question. To me, the most relevant discipline is the history of contacts between human civilizations. I would love to hear what iconoclastic historians like Niall Ferguson and Felipe Fernandez-Armesto would say about the consequences of contact with extraterrestrials in a diverse set of scenarios. Prominent historian William McNeill warned many years ago that the human precedent is not encouraging.

Fifth, we need to bring into this debate younger people who are free of the ideological blinders of both the Cold War and the political and ideological reactions to it. That may mean people less than forty years of age. There are signs of hope. Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David Hackett Fischer put it this way: “After the delusions of political correctness, ideological rage, multiculturalism, postmodernism, historical relativism, and the more extreme forms of academic cynicism, historians today are returning to the foundations of their discipline with a new faith in the possibilities of historical knowledge.”

You ask what our message should be. That has to evolve from discussions among many thoughtful people. I can only offer a suggested formulation: Open eyes, patience and prudence. Accept what our searches tell us about the universe and about the behavior of intelligent beings, whether we like those findings or not. Recognize how new we are on the interstellar scene, and how much we have to learn. In trying to foresee the consequences of contact, keep in mind the only data base we have: our own history. I hope that you will use your journalistic skills to keep this discussion lively, and tolerant.

i’ve said it before… alien invasion just doesn’t make sense on any level under any circumstances.

there are plenty more resources floating around in space than on our planet, and there are probably many more inhabitle planets without a pre-existing technological civilization making invasion not worth the bother.

it’d be like bill gates stealing food from some family in sub-saharan africa: he can afford to go to nice restaurants much closer to home.

@adam “alien invasion just doesn’t make sense on any level under any circumstances.”

But let’s not make the logically flawed argument that because alien invasion makes no sense (assuming that is correct), that aliens are therefore not hostile.

We b;ow up people on the other side of teh planet who cannot possibly do anything to us. Why assume that aliens couldn’t do something similar, like alter our sun?

Reading this fragment of discussion, it strikes me that perceptions of aliens and their motives are similar to the projections various cultures/religions put on their gods, e.g. benign or wrathful. In a similar vein, there is the implied assumption that an alien culture is monolithic – no chance of different groups doing their own thing, just as humans do.

group deciding to do their own thing.

I can’t imagine how even a super-advanced society would ever be able to find us – or others – irrelevant in any way whatsoever, no matter the greatness of their own achievements. It’s in my view that if somebody have gotten to around or past our level of technology, they have probably exercised a great deal of “curiosity”, and I can’t see how even pre-life green goop on other planets could ever stop being interesting unless proven extremely abundant. If that fails, they should in the least be interested in how we’d fit together in the big, star system spanning picture, if that ever turns out to be possible.

I might just be new to the concept, and miss something, though. If anybody would care to clarify this for me, I’d be grateful. (Also, sorry in advance if my English is a little shaky)

On the other hand, I like how Adam compares galactic predation. =)

I see above that somebody beat me (as always) to the idea that an intelligent species which evolved in deadly competition with another intelligence might be benign towards its own kind but have a poisonous fear and hatred of other intelligences. Such a species might not go looking for a fight but react very violently to ETI contact.

I’m actually not very worried about that possibility, since I tend toward the view that high intelligence is rare and may even be unique to humans. It’s more likely that any alien species we encounter will be mentally incomprehensible.

Another possibility I saw pointed out in an essay was that aliens may value trading knowledge (particularly cultural) or ideas. Undisciplined broadcasting may inadvertently give away something extremely valuable or put us at a disadvantage in trade talks.

Alternatively, an alien civilization may decide that we’re too undisciplined to risk talking to (and potentially share information they’ve given us with other civilizations).

Shades of gray between the two extremes.

It is my understanding the “prime directive” of Star Trek culture derives from the history of our own planet. The low tech culture is almost always harmed more than it is helped by contact with a higher tech culture. There are numerous examples where we actually loved them to death. We want to be the higher tech culture when contact happens.

It’s pretty optimistic to expect scientists, even social scientists to make predictions about the social nature of alien species when we’ve barely started to get a scientific understanding on something as simple as our own moral nature.

I feel that this whole conversation is predicated on psychology being a mature science that can make great predictions in novel situations. It isn’t and it can’t.

The best I can offer is to repeat Alex Tolley’s point that we do not know if alien civilisations would have a monolithic structure. I would and to add that this would change everything. Humanity would not be central to their thinking, so I could imagine that their first act might be to annihilate cities that would otherwise frustrate their plans for Earth, and their next act might be to ask if there was anything we might need assistance with.

In some ways the discussion might be premature as we would need to assess the characteristics (in the plural) of any species or group of species we encountered and make judgement calls regarding intent and capability before determining a policy response – which may be based more on ignorance rather than firm information for quite some time after initial contact. The recent paper by Dr Alexander Wendt and Professor Raymond Duvall (2008) in ‘Political Theory’ v36, 4 (which is available in abridged form in Leslie Kean’s latest book and also online, I understand) provides an interesting if controversial perspective, exploring the impact of our current ignorance on current policy positions.

Given the enormous interstellar distances and flight-times I would suspect contact with a robotic intelligence much more likely then meeting actual aliens. As stated earlier in this thread, launching a robotic inter-stellar expedition is not too far beyond our own capabilities. Such a robotic expedition might easily travel for many centuries or even longer, but communication with its owners might still be constrained by the speed of light so it would be almost completely self-sufficient, making its own decisions without calling home first.

The fearful thing about such a robotic expedition might be that it could be programmed as a simple war-machine: destroy any intelligence discovered anywhere on its path. That would eliminate potential threats to the alien society with the benefit of never revealing anything about the location of its owners. A fearful society could send out hundreds of such robotic ships in all directions, and so clear all of its neighbourhood of potential competition without even going through the trouble of searching for or contacting these civilisations first. Simple ‘fire and forget’ missions, they wouldn’t even have to call home, all they would need is sufficient fire-power to destroy anything which moves (or, it it doesn’t move, destroy it anyway, just in case..).

The positive thing about a robotic expedition is that, if it is not intended as a war-machine, it’s basic purpose will probably be its own survival (for which mining asteroids and such for metals, minerals, and water would be much more logical then going through all the trouble of landing on earth) and study of the solar system (including earth). Such a research-expedition is not likely to try to establish contact with our civilisation, it would travel through our solar-system, maybe even orbit earth, but remain silent. Our own, much more modest, unmanned craft have also never tried to ‘hail’ Mars, or Jupiter, or whatever planet, they observe but don’t draw attention to themselves. For a robotic research-vessel there is no benefit in advertising its existence, on designing the ship, its owner would probably be just as much in the blind about what kind of intelligence it might find as we are, so the vessel would be programmed to observe but nobody would take the risk of having it say ‘hello’ without extremely clear benefits to its owner. We are observing microbes, but we aren’t trying to contact them, and an advanced alien civilisation might do the same.

Finally, as has been mentioned before, I can’t think of any specific reason why any alien civilisation would wish to invade earth, there’s nothing on our planet which can’t be found much easier on lower-gravity worlds like asteroids and certain moons. So, either they will simply destroy us, in order to clear their area of possible competition, or they will study us. In both cases, they are not likely to contact us!

What should the message of SETI be? Simply this: that we can’t rule out the possibility of other civilisations out there, and if we want to do well out of any encounter we need to meet them on something approaching equal terms. We want to be like the Japanese, not like the pre-colonial Americans or Africans or Australians.

Therefore we must press vigorously ahead with technological and economic progress: fully reusable spaceplane access to orbit, expanding markets for passenger spaceflight, large-scale development of the near-Earth asteroids, then colonisation of the Main Belt, leading on to interstellar probes and ultimately interstellar travel for our (robotically augmented) human descendants. The vision of Tsiolkovsky, O’Neill and many others.

My own experience with sociologists in the UK is that they are dead against this expansion of our civilisation because it upsets their Marxist principles. It will enhance the power of the already rich and powerful, they moan, forgetting that that is a pre-condition of enhancing the poor and weak, too. These sociologists need to be told firmly why they are wrong, and why Marxism is out of date and irrelevant to modern society, particularly in its galactic context. (See correspondence in Spaceflight magazine, March and April 2011, between myself and one of the authors of the sociological academic text (read: Marxist political tract) “Cosmic Society”.)

NB: we don’t need hostile aliens to threaten us. Mark Presco above is quite right to talk about the weaker partner in an encounter being loved to death. I wrote a brilliant stage play a few years ago (not yet performed) in which Earth was visited by *friendly* aliens. And the bitter conflict between us and them arose precisely because of their wish to help us! (This was my reaction to seeing the unimaginative “Independence Day” movie, ca. 1996.)

I repeat: the message of SETI must be that there *may* be other civilisations out there, they *may* be more advanced than we are, and if we value our own worth then we must continue to grow and expand into our cosmic environment.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

NS said:

“It’s more likely that any alien species we encounter will be mentally incomprehensible.”

A major point that is often missed due to current SETI’s limitations and being constantly fed for decades now an entertainment diet of aliens that look and act like us with only a few variations. Aliens will be ALIEN to us and vice versa.

Expanding on the theme Geert Sassen started regarding robots, it may take the development of an Artilect (Artificial Intellect) to both find a suitably advanced ETI and communicate with it, or even just translate any signals from them.

Astronist (Stephen) – is your play available online? Would love to read it, thank you.

Kepler shows us all crazy shapes and sizes of planets and moons and stars. Galaxy is like a corral reef. A varied habitat. And we are a small fish still in the home nook. We can’t stay hidden forever. We’re getting too big to hide. We’re getting hungry. Most of the nooks and crannies in this reef are empty. Some are not. Some might give us a symbiotic advantage. Or a parasitic advantage. Most of our neighbors are harmless to us. Some are not. Some are stingers, some are egg-layers, some are predators, some are themselves running scared. Some instinctual. Some intelligence. I don’t doubt there is a great galactic ecology filling every possibility. Nature abhors a vacuum. That 12 billion years before mankind arose was a long long LONG time. Lots of water has past under the bridge before we arrived.

The potential threat, I wonder if that is the reason behind the silence.

Give humanity another thousand years of development and there will be only one possible threat to us – an intelligent species that is hostile. However give the distance between stars and the tendency of life to evolve that hostile intelligent species need not be alien, just another branch of humanity.

So maybe that is why the galaxy is silent, technological species don’t want to create existential threats to themselves. It would also explain why every species doesn’t colonize – no species is willing to risk their own racial immortality.

Astronist, I can see where you are coming from, but I don’t think a lot of people have taken on board the Deep Time aspect of Galactic civilisations.

If the current paradigm is anywhere near correct, there ought to be races in the Galaxy billions of years ahead of us. We are not going to catch up with them technologically. It would be an extreme and unlikely coincidence if we were even within a few centuries as our interstellar neighbours in our level of technology.

Proactively advertising our presence to ETs strikes me as unwise. Potential benefits from Contact could be significant but it’s not like humanity is doomed if Contact never takes place. It may take us an extra thousand years to achieve, say, cold fusion, but we are not in a rush.

On the flip side, if the aliens turn out to be hostile and technologically superior and proceed to wipe us out — well, that would be quite a downer. Even if there’s only a 10% chance of that outcome — and I’d guess it’s much higher than 10% for all the reasons stated above — why risk it? Which of us would submit to a 10% chance of death in return for some hypothetical and not particularly life-altering gains?

I should’ve added that I am all for passively listening/looking for SETI. In fact, I view it as crucial to humanity’s security — much like a foreign intelligence service is crucial to a country’s security. It’s not a very romantic view and it may turn out to be needlessly cautious but this is one area where “better safe than sorry” clearly applies.

Mike – Which of us would submit to a 10% chance of death in return for some hypothetical and not particularly life-altering gains?

This is something I’ve never understood about METI, how would broadcasting blindly benefit us in the slightest? Even if there’s someone there and they’re interested in responding, it will be a considerable length of time for their response to reach us for all but the closest stars. Even relatively near stars would result in conversations far too lengthy to be of any use for practical problems.

So why broadcast blindly?

Chris T, you are taking too many practical considerations into account for METI.

You are right that an interstellar conversation would be a very long one in most cases, far beyond the usual level of patience for most human beings. However, METI is often considered and done for other reasons that just a dialog. Now whether it is the right and smart thing to do is another matter, one that we a serious lack of real data on other than our experiences with each other on this one planet. But when did that ever stop people from doing all sorts of things?

The next question is, are other intelligences in the Universe just as rash and irrational as humanity? This is not necessarily a bad thing, please note, because it is often the ones who don’t play it safe and by the rules that often make progress in the end. This also does not mean there aren’t problems from these actions along the way.

Astronist above directed a comment to “NB” — I think he/she might have meant me. Anyway, as I’ve noted on previous threads, in Hawaii (where I live) the native Hawaiian population dropped 90% in the 100 years after initial contact with Europeans and Asians, and are a minority today, even though interaction has been almost entirely peaceful. In Central and South America on the other hand, where the newcomers were bent on overt conquest, native peoples still represent a large fraction of the population and have maintained much of their cultures. So I agree that the overt intentions of ET may have little to do with what actually happens as a result of contact.

Fully agree with Chris, broadcasting blindly seems to me very unwise and quite useless. You don’t start yelling ‘here I am’ if you haven’t got the faintest idea who is listening..

There is another item which seems to me somewhat neglected in the various discussions: what actual benefits would we (or anyone else) get from contact with an alien civilisation? SciFi stories often feature all kinds of interstellar trade, mining of precious metals, or whatever, but this is illogical. Our earth doesn’t have anything worthwhile to offer which can’t be mined at far less costs on myriads of other worlds, asteroids, and comets. Besides, given the costs of interstellar traffic, what could ever be so important that trading it across those distances would be economical?

Colonisation? Just as illogical in my opinion, an alien civilisation which has mastered the art of interstellar traffic won’t bother with colonizing other planets, huge spaceships are a much better option. You can select the most optimal orbit for such an artificial colony, control its atmosphere, radiation-levels, whatever, and if it is threatened by some space-rock, you can simply move it out of the way. A planet is a very inefficient habitat for a really advanced civilisation, they won’t bother with it.

Educate us? Unlikely, they have nothing to gain from it and worst case they would create unwanted competition..

Study us? Possible, for a short while, but would we really be that interesting to any advanced civilisation?

Wipe us out? They might, as has been mentioned before, a fearful civilisation might simply argue that the best survival-strategy rests on eliminating every possible competition within their neighbourhood, although I would guess that any civilisation which is really thousands of years ahead of us won’t bother about us, just as we don’t bother with wiping out all chimpanzees. We are only a possible danger to civilisations which are more or less in our own time-frame, in other words: civilisations which have mastered the art of actually sending their inhabitants to other stars won’t bother with us, but civilisations which are just advanced enough to send robot-ships might consider us a threat..

Looking at above options, once again, I doesn’t sound like a very good idea for us to start yelling ‘here we are’, I would remain silent and listen real good..

Keep in mind that any ETI coming to Earth will have traveled so much farther than any human ever has on this planet. It will require methods much more involved and sophisticated than a water ship or plane. The environment an ETI will be moving through will also be unlike anything on Earth. Add to this the fact that they will be aliens and you will have a situation that may not mirror what happened on Earth at all. Besides, if they do want to destroy us, they don’t need to send themselves and we won’t know what hit us.

@Mike “why risk it? Which of us would submit to a 10% chance of death in return for some hypothetical and not particularly life-altering gains?”

The religious have often done that, from early Christians in Rome, to the 100% chance of death for suicide bombers today. Arguable participating in a war is done for just that sort of trade off. Dangerous occupations might be another example. There are therefore many examples of humans taking such a risk, even at the national level.

ljk – However, METI is often considered and done for other reasons that just a dialog.

This was precisely what I was hoping someone would answer. Once you’ve eliminated the practical, what’s left?

I should hope it’s not just because someone has a vastly inflated view of their own self importance.

Chris T., METI is done for the following reasons. This list is not conclusive but these are the main points. Others are welcome to add their own ideas.

1. To get the attention of other intelligences in a very big, very noisy, very busy, and very spacious galaxy (and sometimes beyond). Think of it as an aid to SETI.

2. To have an actual dialogue with ETI. Yes they will be long conversations, but it is hoped that we will learn a lot in the process and that humanity and/or our world may offer something of interest to them to keep the dialogue going.

3. Free speech on a cosmic scale. Some who do METI consider it their right to be able to speak to the Cosmos just like the small group of scientists who have done so in the past. They don’t like the fact that someone else is representing them and all of humanity and then telling them they cannot do it because of the potential danger. So I guess that is a bit of an ego involved too. It also showcases that in any endeavor there will always be some humans trying to break the rules no matter what the consequences. The reasons range from personal freedom to insanity.

4. The hope that an advanced and benign ETI will be enticed to come to Earth and “save” us from our problems. All I can say to this is, while learning from an alien species may certainly benefit our understanding of existence and aid us in progress, if an ETI does come to visit, it may be very foolish to assume they are traveling unknown light years and not want anything more in return than to see us improve ourselves. The expectations and price may not be sinister, but there is the possibility of losing ourselves in the process.

5. Publicity, often to make money. The last few years have seen a number of METI events aimed more at generating revenue from the occupants of this planet than adding to the wisdom of another species or our own. As just a few examples: A Doritos ad was sent to a nearby star system to help pay for UK science; the sub-par remake of the SF film The Day the Earth Stood Still was beamed into deep space (how was that was I don’t know considering the theme of the remake). METI has also been done to commemorate events in a big way: The first Arecibo Message was actually done to celebrate the new aluminum panels put on the radio telescope’s net to increase its abilities.

6. Art – Some METI were done as artistic expression, which could be someone combined with freedom of speech above. MIT artist in residence Joe Davis has sent several DNA METI transmissions into the galaxy over the years, the latest being at Arecibo in 2009 and which is chronicled on Centauri Dreams.

Now whether the other technological residents of the Universe will behave and react in a way similar to the above due to the basic nature of being intelligent and aware, or end up going down other paths we can scarcely imagine, remains to be seen.

Might I say that the extent of ET interest in Earth would depend on how rare such planets are? Just because it is very unlikely Earth would be a good place for them to inhabit does not equate to them having no interest in it or plans for it.

Might I also claim that the most dangerous reason so far given here for METI is ljk’s reason 4? If we are having problems with our relationship with Earth or with relating to other sectors of humanity, then such a message equates to a request that the ‘footprint’ of humanity be erased from the Earth, or that we need to be told what to do.

Extraterrestrials who respond in concordance to such a message, and that possess a disproportionately high interest in humanity, are likely wipe out our civilisation or take it over, because they would hate to see such ongoing suffering, particularly in fairly intelligent animals such as humans. Extraterrestrial respondents with a disproportionately low interest in humanity would prioritise the rebalancing of Earth ecology over human wants.

@Alex Tolley… there’re plenty of instances of people risking or even choosing death but in all such cases they are driven by some combination of honor, duty, religion, desperation, or delusion. METI does not fall in any of those of those categories . There is no cosmic honor or duty in seeking out ETs (though yes, it would certainly be “cool”), we do not worship them, we are not desperate to meet them, and we are presumably not delusional.

The only truly globally dangerous act of humanity I’m aware of is the development and proliferation of nuclear weapons. At its time the development of nuclear weapons was almost certainly the only logical choice — should the Axis powers have developed them first the consequences would have been even more terrible. METI is in no way similar since there are absolutely no terrible consequences to the absence of METI. We wouldn’t (and shouldn’t) even have to give the passive SETI when we abandon METI.

The benefits of METI, as listed above by ljk are rather abstract, save for #4 which, as ljk points out, may have its own perils. The possibility of being wiped out is very real, even if we can argue about its probability. Even if Earth’s ecosystem was full of competing species helping each other survive and human history was full of countries and civilizations peacefully co-existing — even then we could not fully discount the possibility of hostile and mobile ETs. Of course our own reality and history are much more savage than that so we should assign the correspondingly high probability to the possibility of killer ETs.

So, to summarize:

– no life-altering benefits from METI

– no need or necessity for METI other than general curiosity

– no adverse consequences to abandoning METI

– passive SETI is a near-perfect and completely safe substitute for METI

– non-zero (and possibly very high) likelihood of humanity’s demise with METI.

What other human endeavor has had such an ugly risk-reward profile?

Quote from

http://www.cplire.ru/html/ra&sr/irm/Making_a_Case_for_METI.html

In conclusion, we subscribe to one possible solution to the Fermi Paradox: Suppose each extraterrestrial civilization in the Milky Way has been FRIGHTENED BY ITS OWN SETI leaders into believing that sending messages to other stars is just too risky. Then it is possible we live in a galaxy where everyone is listening and no one is speaking. In order to learn of each others’ existence – and science – someone has to make the first move…

@Mike “METI…. There is no cosmic honor or duty in seeking out ETs …, we do not worship them, we are not desperate to meet them, and we are presumably not delusional. “

I think it is arguable that:

1. Science naturally looks to understand all of the universe, so there is at least the equivalent of ‘duty” to seek them out to meet this goal.

2. There is at least a strain of seeing ETIs as gods. Are they any different from the invisible gods we have today? ETI cults?

3. Humans have exhibited plenty of delusional behaviors, worshiping invisible sky people is one of them.

If humans gain benefit from religious practices, why would one based on ETIs be any different? Is METI any different from building a church or cathedral and using it to communicate with the supreme being[s] of the religion? If ETIs really did exist, and if they were believed benevolent, then there possible payoff would meet your original criterion of a 10% probability of death for a hypothetical benefit.

But let’s be clear, METI is essentially useless unless the listeners are relatively close to us, or have ways of detecting our signals that get around the c limitation. Without either of those 2 conditions, METI is less effective than throwing a message in a bottle into the ocean.

If ETIs are out there, and they want to monitor activity for any purpose, they will already be monitoring us in some fashion. Arguing about METI is like an ant colony thinking about putting out a strong pheromone signal to attract the attention of humans. Humans already know about the colony, may have already studied it in detail, and what happens next is not really in any way controlled by the ant colony. Although tehe queen taking flight with a few drones is a little like an interstellar colonizing effort

Never having contact with an ETI is another possibility. Each of us have personal thoughts continuously running through our minds in complete privacy. This individual privacy is considered sacrosanct in human beings, vital to personal evolution. Perhaps the importance of privacy works on a planetary level as well. Here’s one reason: It’s great to know that we human beings have evolved totally on our own to where we are today. If we discover alien manipulation in our evolution, that might rob us of something.

Just a thought, I realize it’s far-fetched. But the importance of privacy on a personal level has many parallels on a planetary level. The universe is set up for privacy.

My apologies if this is off topic.

This was an interesting post, since it gets beyond some of the tired ideas of benign / hostile. There are many, many possible dimensions to contact and results of contact.

I would point out that chance will probably play a huge role, since the last thing we should expect is uniformity in anything as complex as an old ETI. Forgetting diversity and diversification seems to be a common problem in these discussions.

(1) Human motivations, beliefs, and actions vary widely. Some people believe in METI and have tried it, others see it at as very risky. Even on our one little planet, we have a diverse set of responses to the possibility of ETIs. As social complexity continues to expand in human civilization(s), I’d expect greater range of opinions and behaviors vis-a-vis possible aliens.

(2) Deep time and the vastness of space suggest that aliens, even if they originated in once spot, would become vastly varied. If they do exist, we should expect more of a diverse ecology in the Galaxy. The “space” of possible roles in alien ecologies / societies will no doubt be at least as diverse as Earth. We’ve got predators, prey, parasites, primary producers, missionaries, criminals, social workers, warriors, sociopaths, researchers, outcasts, homeless, adventurers, etc., etc.,. These can be mirrored elsewhere and include many far more alien kinds of motivations, beliefs, and niches. We’re not uniform here on Earth, so there’s no reason why should ETI’s be uniform.

I suppose the impact of SETI’s success would really depend on luck. One can only hope that long term evolutionary trends and selection pressures favor contact with critters (or robots) that won’t be harmful (for whatever reason). For example, if you were to meet a human being at random, it’s very unlikely you’ll meet a sociopath, more likely you’ll meet someone with some moral / ethical habits. But you could get unlucky.

Great to read everyone’s comments in this discussion, and thank you to Paul for allowing myself and Michael the opportunity to have this dialogue. Although nothing is going to be decided here, no consensus reached, it at least gets us thinking about this topic, which is crucial because as Kathryn Denning told me, “nobody is thinking about this hard enough.” Over the next few years hopefully more discussions like this, on websites such as Centauri Dreams, as well as at conferences all over the world featuring experts from all areas of physical and social sciences, and the public, will enrich the debate. Even if we never contact ETI, the understanding gained through our discussions of the subject may help us better understand the nature of contact between our own people, and thus our own history.

To respond/comment on a couple of people’s points:

Rob Henry – yes, we are still learning about human psychology, human culture, and the evolution of culture and intelligence. But if it is the case that psychology is not yet a mature science, then why do we allow some researchers to make sweeping generalisations when they apply these areas to ETI? We’re suggesting that these assumptions should at least be looked at and questioned before being applied. Ideally we’d want more information about the possibilities for ETI before we dived headlong into this debate, but the horse has already bolted – we are already trying to initiate contact. So now is the time to talk about this.

And I totally agree with those of you who say that ET civilisations will not be mono-cultural. These are what I like to call ‘Star Trek cultures’ – the Klingons are all warriors and bark on about honour, the Vulcans are all logical thinkers, the Romulans are all sneaky, the Ferengi all greedy etc. And we don’t just do it in science fiction; we also have a worrying tendency to do it to different societies right here on Earth. Unless we’re dealing with a hive mind (which Star Trek did get right with the Borg) or some kind of advanced ‘overmind’ then we have to consider the possibility that among each civilisation there will be different groups with differing levels of interest in us. It makes any contact with ETI that little bit more of a minefield.

Astronist – I share the general idea of your ‘message of SETI’ – we don’t know what is out there, but to find out we need to progress and explore before we should feel confident enough to commit to a programme of METI. Perhaps the emphasis of SETI’s sales pitch could focus more on exploring both space and our own nature, our own place in the Universe, than on just contact (which may take centuries in terms of sending messages and receiving replies). Note that I don’t say we should never transmit, but only to do so when we know more about what we are dealing with so that we are better prepared to initiate contact, although I cannot say at what stage that will be.

Geert Sassen – what would Earth have to offer ETI? David Brin suggests that all we have is our culture, and that we should therefore not beam it into space for free. Would ETI really be interested in our culture? I honestly don’t know. At first such a notion sounds parochial, but I’ve heard the SETI Institute’s Doug Vakoch talk about how science progresses a little bit like a mountain climber ascending towards a peak, but that there may be different routes up that mountain, or some climbers might even be climbing different mountains. The point of the analogy is that our culture, our view of the nature of the Universe, may be slightly different to those of other intelligences. I can imagine advanced ETI collecting these different cultures, different viewpoints, from species all across the Galaxy to gain a better understanding of the Universe. It’s a rather romantic notion, but I like it, although it still doesn’t mean that contact will necessarily be beneficial for us.

ljk and Rob Henry – the idea that some people view ETI as gods or saviours worries me, not so much from the philosophical aspect, but from the point of view that I’d prefer us to focus on solving our own problems. But you may find the Earth Speaks project (http://earthspeaks.seti.org/), run by Doug Vakoch at the SETI Institute, illuminating. Its a sociology experiment to collect messages to ETI from the public (not to transmit, I should mention – it’s more of a ‘what if you could talk to aliens’ kind of thing) and shows that a lot of people would ask ETI to save us.

I have no idea whether ETI exists or not, but I don’t think this debate is futile because we can learn so much from it, if not about ET then about ourselves. And if ETI does exist, and we do make contact, I would hope that discussions like this one will at least help inform us so that we can navigate through the dangers of contact and emerge on the other side as a better, more prosperous human society.

Happy Easter!

Keith

Hi All

Then there’s this possibility…

On the Origin and Evolution of Life in the Galaxy

On the Origin and Evolution of Life in the Galaxy

Authors: Michael McCabe, Holly Lucas

(Submitted on 17 Mar 2011)

Abstract: A simple stochastic model for evolution, based upon the need to pass a sequence of n critical steps (Carter 1983, Watson 2008) is applied to both terrestrial and extraterrestrial origins of life. In the former case, the time at which humans have emerged during the habitable period of the Earth suggests a value of n = 4. Progressively adding earlier evolutionary transitions (Maynard Smith and Szathmary, 1995) gives an optimum fit when n = 5, implying either that their initial transitions are not critical or that habitability began around 6 Ga ago. The origin of life on Mars or elsewhere within the Solar System is excluded by the latter case and the simple anthropic argument is that extraterrestrial life is scarce in the Universe because it does not have time to evolve. Alternatively, the timescale can be extended if the migration of basic progenotic material to Earth is possible. If extra transitions are included in the model to allow for Earth migration, then the start of habitability needs to be even earlier than 6 Ga ago. Our present understanding of Galactic habitability and dynamics does not exclude this possibility. We conclude that Galactic punctuated equilibrium (Cirkovic et al. 2009), proposed as a way round the anthropic problem, is not the only way of making life more common in the Galaxy.

@Alex Tolley… appreciate your response. The presence of UFO cults is no reason for all of humanity to take on the risk of being exterminated in the name of METI. A cult directly or indirectly harming people in the name of its religion is illegal in the US and most countries in the world. Even if we view METI as a sort of religious or spiritual pursuit, it should be subject to the same constraints. Going with the 10% hostile/mobile ET probability, METI would be expected to result in ~700,000,000 human deaths (10% of all humans today). Yikes!

I do agree somewhat with your argument for the “duty” of scientists to explore the unknown, but there are other scientific pursuits that are frowned upon if not outright forbidden because they are potentially not safe (e.g. bioengineering killer viruses). METI should fall in this category.

I am not in a position to judge how much or little METI increases the chances of Contact relative to all the radio emissions we produce as part of everyday life. If powerful enough and (un-)luckily targeted then it seems at least plausible that a METI burst may be what causes faraway ETs to detect our presence a few centuries or millennia down the road. But yes, overall, I would agree with you that chances of Contact via METI are poor, both in absolute and relative (to SETI or to ETs landing by the Washington Monument) senses.

So, either METI is a priory hopeless and is a waste of money and resources (which as we all know are extremely hard to come by for all space sciences, let alone SETI) or it’s a ~10% : ~90% gamble on extermination of humanity : some, likely abstract, gain. And much of the same gain with zero chance of extermination could be achieved through passive SETI.

We probably all agree that the key question driving all these efforts is “are we alone?”, not “what technologies can we learn from the ETs?”. Devoting available resources to passive SETI over METI would be more conducive to answering this key question while also minimizing the potential unpleasantries of being exterminated.

In my opinion, the medieval obscurantism and the witch-hunt are not different from the shaman’s spell about the deadly dangers of METI.

Adam, this modelling of the emergence of life and intelligence, that was further elaborated on by McCabe and Lucas has been a work of genius. It is easy to be so drawn by such beauty that one forget what it is based on. Firstly, statistics on a sample space of one allow no way to estimate error, so the assumption of this emergence being a series of approximately rare transitions serves greater purpose than just trying to follow the evidence. Other assumptions are even more of a problem if a newcomer to this model does not know of them. These are as follows.

1 The timing of the abiogenesis is unconstrained after the Late Heavy Bombardment. We thus can’t believe that life began in an oceanic soup of organics (which would quickly ‘wind down’ with time) or that chemical evolution was driven by meteoric impacts.

2 That we know how much longer it is possible for Earth to support complex life.

3 That geological or other environmental transformation process on Earth played no role in this process. For example we cannot believe that intelligent life needed atmospheric oxygen levels above 10 000 Pascals to evolve.

Note that we could still salvage a fair bit from the model while working under other assumptions, but we would first have to do some reworking.

Oops. Above I criticized the Carter model (actually I thought it originated with Ernst Mayr, but never mind) as used by McCabe and Lucus for its ability to mislead. In my haste to do so I incorrectly stated that the major evolutionary transitions are assumed to have similar rarity, when there actual required commonality is that every step involved in any one of those transitions must occur within a span that is much much smaller than the time available for evolution on Earth, and the probability of any one of these transitions occurring within this Earthly time frame must be much much lower than even.

That said, my major error was in not cutting to the chase. The only thing that this model is really good at is evaluating how many such steps have occurred in our evolution AFTER assuming that evolution has such a nature. The only other thing that this model seems moderately good at is in assessing whether the timing of transitions seen in the fossil record is in any way consistent with them being improbable.

Mike said on April 24, 2011:

“So, either METI is a priory hopeless and is a waste of money and resources (which as we all know are extremely hard to come by for all space sciences, let alone SETI) or it’s a ~10% : ~90% gamble on extermination of humanity….”

The vast majority or SETI and METI projects are privately funded these days. NASA briefly had a SETI program in 1992 but it was shut down the next year due in large part to the efforts of some ignorant politicians. So you and others don’t have to worry about your tax money going to the aliens.

Even if they did, what the search has gotten in funding over the decades is paltry compared to most other scientific endeavors; a vast disparity compared to the importance of finding extraterrestrial life.

And as I have said in several articles on Centauri Dreams, there are few practical reasons for an ETI to harm or destroy humanity, but if they were going to, it would be done powerfully and quickly and there would be darn little we could do about it. Think of it like a big earthquake.

Wow! The number and intensity of these comments speaks volumes about human concern on such big questions for which there is so little data from which to deduce conclusions. Clearly, this is one of those “important questions” that needs impartial and reliable tracking.

New arxiv paper:

“Would contact with extraterrestrials benefit or harm humanity?

A scenario analysis”

http://arxiv.org/abs/1104.4462

Zaitsev – The point of the article is that there is a large range of risks presented from scenarios that don’t reside at the extremes of the spectrum (homicidal or altruistic). As has been further pointed out in the discussion, the potential benefits are not at all clear at this time. Prudence would dictate, until risks and benefits can be better assessed, we should wait before blindly shouting into the universe.

Chris T – The fact that our unusual atmosphere that contains oxygen, long “screams” into space, over 200 million years! Any advanced civilization long ago discovered this unusual planet! And after the discovery began monitoring a planet in order to detect in time a reasonable life. And found it first and foremost on the emission of radar signals. Case that comparison of the total number of the radar astronomy transmissions with respect to that used for sending messages to extra-terrestrial civilizations reveals that the probability of detection of the radio signals to extraterrestrials (ETs) is one million times smaller than that of the radar signals used to study planets and asteroids in the Solar System.

See “Detection Probability of Terrestrial Radio Signals by a Hostile Super-civilization” at:

http://jre.cplire.ru/jre/may08/index_e.html

Ljk, you write “there are few practical reasons for an ETI to harm or destroy humanity”. Surely this assessment turns on the assumption that their only interest in our system and planet was our current civilisation (note that a more general interest in our species will not suffice here). What strikes me, is that in any other circumstances one could be equally struck that “there are few practical reasons for an ETI to protect or conserve humans or their institutions”.

There is no additional threat since anyone capable of communicating with us will already be capapble of detecting life (and industry) here. Bacteria gave our position away many years ago.

Rob Henry, read the rest of the sentence you quote me on. I never said there weren’t any risks from an encounter with an alien intelligence, nor am I assuming that they would only go after us and our world at this particular point in history.

However, unlike the manners depicted in the glut of SF films and novels regarding alien invasions, if an ETI wanted to destroy us, there are a number of ways they could do so which we would have virtually no defense against at this point. What we need to find out is, why hasn’t this happened already?

over 200 million years!

Way longer than that, free oxygen should have been detectable around 2.5 billion years ago. This only begs the question, why haven’t they tried to contact us if they know about us? Either they don’t know about humanity or they’re not interested in contacting us. The former brings us back discussing the potential risks of signaling an ETI and the latter makes METI rather pointless.

ljk the point of this article is that we should examine the ETI perspective of us with maddening pedantry if have any chance of understanding their potential contact. With that in mind, and taking your suggestion, I find that the second half of that sentence starts “if they were going to [destroy humanity] it would be done powerfully and quickly”. Surely this would only indicated from our own historic evidence, if they saw us as near equals. In any other circumstances it would be leisurely and slow, such as the mysterious and well documented worldwide drop in sperm counts that is actually occurring right now.

I apologise for being so picky, and admit that in most any other debate this, and that previous point, would be to minor to bring up.

Chris T – What a pity that you have read only the first part of my answer…

For those of you still worried about SETI being a drain on the economy or just a waste of time in general, worry no more:

http://www.universetoday.com/85121/budget-woes-put-setis-allen-telescope-array-into-hibernation/

SETI is sent to the back of the bus where it can once again scrape and beg for a ride with the Big Boys of Science.

Just so you know: The amount of money needed to keep ATA running is the same that MTV will be paying the cast of Jersey Shore for future episodes.

Chris T, almost everyone in this forum would agree that any advanced and inquisitive ETI to which our modern METI messages could reach, should by now be aware that high metabolism life forms inhabit Earth. Most of these are probably aware of signs that the industry of early technological civilization has also started here. Thus I agree that making the assumption that they care little about us is one of our most solid starting points for examining the mindset of any likely to receive such a signal.

What I disagree with is that the knowledge that we wish to communicate with them could have no conceivable effect on them. Also, I feel that the more powerful and deeper reaching METI that we would be capable of sending a few decades hence, might reach much further than Earth’s biological signs.

ljk, that SETI news would indeed be truly great to many of us in this forum if the money had been redeployed in searching our own system for signs of Bracewell probes or other artificial structures (if they’re there they’re here by Fermi). Sadly, in this case it just seems a symptom of an insular outlook. If that does not change we really are doomed, so all any one of us can do is party on and rejoice in that Jersey Shore news!