Today we continue with responses to the Request for Information from the 100 Year Starship study. Kelvin Long is senior designer and co-founder of Project Icarus, the ambitious attempt to design a fusion starship. A joint project of the British Interplanetary Society and the Tau Zero Foundation, Project Icarus takes its inspiration from the original Project Daedalus, updating and extending it with new thinking and new technologies. Here Kelvin considers how a research organization tasked with developing something as ambitious as a starship can function and prosper. And he would have considerable insight into the matter — as a Project Icarus consultant, I’ve never seen so dedicated and energetic a team as the one he put together. Its final report will be an essential work in interstellar propulsion studies.

Kelvin Long completed his Bachelors degree in Aerospace Engineering and Masters degree in Astrophysics at Queen Mary College, University of London. He is a Fellow of The British Interplanetary Society, Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, Member of the American Institute Aeronautics & Astronautics, a Chartered Physicist and a Practitioner of The Tau Zero Foundation. He has published numerous articles and papers on various aspects of space travel. His Ph.D work is on the topic of Inertial Confinement Fusion, a key player in both the Daedalus and Icarus designs.

Kelvin F Long[ref]Note that the author is a British National based in the United Kingdom.[/ref]

BEng Msc CPhys FBIS FRAS MAIAA

Icarus Interstellar & Tau Zero Foundation (non-profits)

Abstract

This is a response to the DARPA solicitation requesting information for the 100 Year Starship Study. Preliminary ideas for a (long term) research model and Interstellar Institute for Aerospace Research (IIAR) are presented. The views expressed in this document represent the authors only and not the official views of Icarus Interstellar or the Tau Zero Foundation. This paper is a submission of the Project Icarus Study Group.

1 Introduction

The ambition of interstellar flight has been the subject of many science fiction novels [1-3] and continues to inspire a large number of academic papers and books [4-9]. Despite this interest, it has generally been the public belief that interstellar flight is speculative engineering. In 1969 man landed on the Moon, but before that stupendous achievement could be realized it had to first be demonstrated that such a thing was possible. Hence in the 1930s members of the British Interplanetary Society (BIS) undertook a study for a Lunar Lander [10], presenting the first such engineering concept and moving the subject from speculative fiction to credible engineering. Similarly, before the first interstellar probe can be launched it must first be demonstrated that such a thing is feasible. In the year 2033 the BIS will have reached its 100th anniversary and its Journal, JBIS, has been the home of visionary thinking since its first publication in 1934 – it is the oldest astronautical Journal in the world [11]. Members of the BIS were also the first in history to publish an academic paper on the subject of interstellar flight [12] and in the 1970s members pioneered the future by the design of a theoretical Starship called Project Daedalus [13]. Using an inertial confined fusion based propulsion system the probe would reach its stellar target in around half a century. Project Icarus was founded in 2009 and is an international project to redesign the Daedalus vehicle with modern knowledge as a ‘designer capability’ exercise [14]. An international team has been assembled and is hard at work on the calculations in a (volunteer) capacity. All of the above demonstrates that the “First Steps” towards the stars have already been made in advance of the DARPA RFI. The “Second Step” (for DARPA, TZF or others) is to bring this research together into a century long co-ordinated program. In reality, the first interstellar probe launch is likely at best one to two centuries away as has been consistently demonstrated [15-18]. To launch even an unmanned interstellar probe in advance of the year 2100 would likely require significant and sustained technology investments several times greater than those of today [19].

The means by which the first interstellar probe is to be propelled remains a matter of discussion awaiting technological breakthroughs. Although some clear contenders have emerged in recent decades, from external nuclear pulse [20], to fusion engines [21], to sail beaming systems [22-24]. Other more exotic alternatives includes antimatter based systems [25] or the use of interstellar ramjets [26] which requires no on vehicle propellant. One aspect that could changes all this is the discovery of a breakthrough method of propulsion physics such as proposed for the famed warp drive of science fiction, now the subject of rigorous metric engineering using the tools of General Relativity and Quantum Field Theory [27-29]. The potential for such propulsion systems (as well as others) and how to manage such research has been well studied by others [30-31]. The launch of human based Starships will require massive engineering and therefore large infrastructure requirements, as evidenced by studies of Worlds Ships [32-33], placing it many centuries into the future. Other than Project Orion and Project Daedalus, various vehicle design studies have been undertaken historically that are relevant to the design of a Starship, to differing degrees of engineering accuracy. This includes VISTA [34], AIMStar [35] and the student study LONGSHOT [36], for example.

How can the pace of interstellar research be accelerated so as to facilitate an earlier launch window? One method is to think about the interstellar roadmap by planning interstellar precursor missions which go to 200 AU, 1000 AU and beyond. Several such proposals have been made over the years [37-40]. What makes such proposals feasible (as well as the full interstellar missions) is consistency with the Technology Readiness Levels [41]. These are the guiding tool for all aerospace development even at national space agencies [42] and the emphasis for bringing about an interstellar mission must be to encourage and facilitate research into low TRL (~1-3) propulsion schemes and other technologies. An approach for the planning of visionary technology development programmes, the Horizon Mission Methodology, has been constructed and is an ideal tool for this purpose [43]. Although in past generations significant (largely theoretical) progress has been made towards the eventual launch of the first interstellar mission, this research has been largely uncoordinated, unfocussed and performed by volunteers. If the first launch of an interstellar probe is indeed to take place in the next two centuries, then what is required is a change of strategy to include a significant investment program and the formation of an Interstellar Institute for Aerospace Research (IIAR). The proposal for an Interstellar Institute has also been made by the former NASA physicist and current President of the Tau Zero Foundation Marc Millis, in private communication, and this is one of the long term aspirations of the Foundation.

An Interstellar Institute would coordinate research relating to all aspects of an interstellar mission, from the manufacturing and assembly, launch and construction, fuel generation or acquisition, to communications and science monitoring. Such a body should also encourage research spanning the range of propulsion options. By not closing off any options today each method progressives incrementally until a front runner clearly emerges – ad astra incrementis. The Institute logo spells out the letters of the name. The trajectory of a spacecraft is shown, passing three stars which get progressively larger, emphasising that with incremental steps the stars will get closer. The spacecraft exceeds the position of the stars and continues out into the galaxy showing that with visionary (but credible) goals anything is possible. The Institutes motto would be along the lines “Leading Astronautical Research to the Stars”, emphasising academic rigour in all studies.

2 Research Model

In this document we describe an optimistic (long term) vision for an Interstellar Institute manned by permanent staff, hosting resident academics and assuming the support of wealthy philanthropist(s) to get it started (but not to sustain it). If there were an Interstellar Institute this would attract academics from around the world to come together for weeks or months at a time to jointly work on some of the major technical issues or explore a new area of physics where a fundamental breakthrough in our understanding may come. Design teams could also be assembled to work on specific problems, such as: development of technology for the unfurling of a solar sail in deep space; engineering an interstellar ramjet; reducing the negative energy requirements of a warp drive; or finding ways of mining Helium-3 from the gas giants in a cost effective way. The basis of all research will be to improve the Technology Readiness Levels of a diverse range of spacecraft technologies, particularly pertaining to propulsion. It would also be the location for a major conference and would act as the international focus point for all interstellar related research. This is what we need to make interstellar research move substantially forward and allow innovative ideas to emerge and be applied efficiently to the progression of the subject. It needs to be moved from the volunteer sidelines of science, given some major investment, and an institute to focus the research and provide an exciting atmosphere where an optimistic vision for space exploration exists. The Aim, Vision and Mission of the Institute are described as follows:

- Aim : To co-ordinate and facilitate international research excellence towards solving the engineering and physics obstacles associated with interstellar flight and to spur technological breakthroughs.

- Vision : To encourage robotic and human missions to the stars in the coming centuries.

- Mission : [1] To be proactive in co-coordinating international research associated with international flight and to demonstrate research leadership in the field of astronautics [2] To conduct outstanding educational activities to better communicate to the public the importance and the credible feasibility of interstellar flight [3] To work towards an agreed set of short, medium and long terms goals that are consistent with the Institutes optimistic vision for interstellar flight.

2.1 Organizational Governance & Finance Model

A non-profit organization manned largely by volunteers does not have the man power or resources to undertake a large scale research program greater than 10s of people. A business does have this capacity but is subject to risks associated with financial markets and competition. Government can protect itself against risk and can manage large scale programs; however, inherent bureaucracy, micro-management and leadership changes due to changing political policies create an environment that is unstable, costly (usually measured in billions of dollars) and over time become less flexible to positive innovation and change. The best strategy therefore is to combine the best of all three structures whilst throwing away the worst parts.

The cost of the Institute construction is expected to be of order ~$30-50 million. The cost of the initial research investment program is expected to be of order ~$100 million. Annual funding programs of order ~$10-20 million per year are expected until self-revenue generation emerges. In essence the Institute is a non-profit research body, more similar to a University rather than an industrial company, which specialises in research and academic educational programmes in physics and engineering relating to deep space missions.

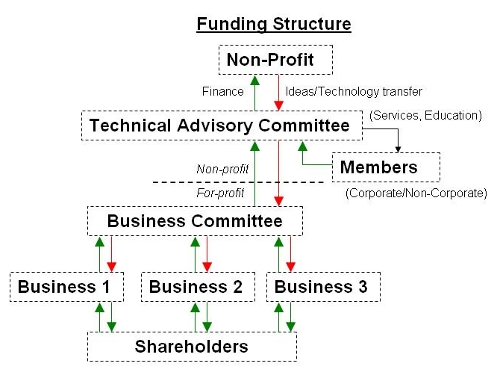

The Interstellar Institute would be founded around the year 2020, allowing time for sufficient planning and construction work. The initial start fund program to begin the planning stage is of order several hundred thousand dollars, consistent with the DARPA RFI. The funding structure is described in the diagram above, with innovative technologies leading to patents and new engineering products for space. The organisation that comes closest to this model is the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Canada, which was founded in 1999 by Mike Lazaridis who owns the Blackberry Company. New Scientist has said of PI: “…what may be the most ambitious intellectual experiment on Earth” [44]. The Interstellar Institute can exceed this by reaching for new heights in intellectual leadership and turning the energies of international groups of volunteers into a coordinated research programme that is focused on the launch of the first interstellar probe in this century or the next.

2.2 Organizational Structure

The Institute would be an independent non-profit organized with a Technical Advisory Committee acting as the Board of Directors to oversee all activities. A core membership would support the non-profit status. The core of its work program consists of three elements:

1. Theoretical research to produce breakthrough solutions to problems in physics and engineering relating to deep space missions utilizing a variety of propulsion systems and technologies, including concept development for real spacecraft designs.

2. Education to bring about a greater awareness of the viability for future interstellar missions and how they might impact our cultural and technological growth.

3. Public outreach to communicate the vision and feasibility of interstellar travel and inspire the world that such a vision is essential to a secure and peaceful future for the human race in space.

Additionally, the Institute may undertake the following two activities:

1. Laboratory based experiments to improve the Technology Readiness Levels of key systems and sub-systems likely required for a deep space mission.

2. Contributions to actual space missions by development of a sub-system that would be required for a deep space mission.

The majority of the work undertaken by the Institute is expected to be theoretically based (~70%), performed by the visiting academics, with perhaps a minor element (~10%) dedicated to actual laboratory and space environment mission development. The remainder of the program will be dedicated to education and public outreach (~20%). Typically the Institute would consist of around 30 administrative and facility staff, 20 research co-coordinators and around 150-200 resident researchers, of which two thirds would be visiting. All staff will be designated Support, Management, Resident Researcher or Visiting Researcher. Additionally, non-academics/non- professionals (common in this field) who has showing a grasp of the technical issues may also become visiting residents, awarded on a grant basis, regardless of background.

The educational program would consist of regular symposia and conferences in a lively and dynamic research atmosphere. The highlight would be a bi-annual Conference for Interstellar Flight, reviewing the latest research in the field. One aspect of the outstanding educational program would be an annual summer residential course, taught by a combination of permanent and visiting residents. The course will lead to a Postgraduate Certificate in Interstellar Engineering, to be awarded by a local University with their co-operation and involvement. The syllabus would cover all aspects of spacecraft design technology and mission performance; from communications to structure and materials to propulsion. Orbital mechanics and trajectory analysis would also be included, as well as basic planetary and solar physics science. There is also the potential for creating a full Masters program in Interstellar Engineering, to include a design project, as part of a summer school attended twice in succession. Doctoral research programs may also be possible. The Institute is to be a world leader in the implementation of the latest technologies in the everyday activities of its residents with many symposia and conferences transmitted live to the World Wide Web. On occasions the entrance lounge of the Institute can be easily turned into a banquet hall for conference dinners whilst listening to some cultural music. The entrance hall would also be an exhibition arena showcasing either the latest technologies or artwork which helps us to understand the challenges of humans in space.

The Institute governing structure is now defined.

– Institute Executive: Director Institute; Deputy Director; Executive Committee (Division Heads + selected volunteer external advisors).

– Division of Research Management: Division Head; Deputy Division Head; Building Management; Office Administration; Publications & Media; Building Maintenance (facilities, structure, gardening, health & safety); Business & Finance; Human Resources, Business Marketing & Finance; Archives & Exhibition (museum, library); Catering Facilities; IT Services (maintaining on site computers, networks and supercomputing clusters); Office of Future Developments (expansion of Institute); Office of International Research Co- ordination (co-coordinating residents/sabbaticals); Office of Space Mission Liaison (co- coordinating interactions with commercial/agency spacecraft missions); Office of Laboratory Research (management of on site laboratories or test technology).

– Division of Science & Technology: Division Head; Senior Advisory Committee; Leader Instruments & Payload Group; Leader Computing & Electronics Group; Leader Power Systems & Thermal Control Group; Leader Structure & Materials Group; Leader Risk, Reliability & Spacecraft Protection Group; Leader Space Infrastructure & Vehicle Assembly Group; Leader Space Communications, Navigation & Guidance Control Group; Leader Astronomy & Exploration Group; Leader Human Colonization.

– Division of Reacting Engines: Division Head; Senior Advisory Committee; Chemical Propulsion Group; Electric Propulsion Group; Nuclear Fission Group; Nuclear Fusion Group; Antimatter propulsion Group; Advanced Particles & Fields Group.

– Division of Propellantless Propulsion: Division Head; Senior Advisory Committee; Solar & Microwave Sails Group; Particle Beams Group; Interstellar Ramjets Group; Mass Drivers Group.

– Division of Breakthrough Physics: Division Head; Senior Advisory Committee; Leader Space Drives Group (dean drive, disjunction drive); Leader Metric Engineering Group (warp drive, black holes, worm holes); Leader Particle & Information Transmission (teleportation, tachyons).

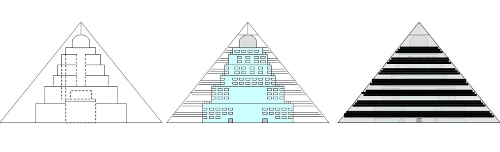

3 The Interstellar Institute for Aerospace Research

The building for the Interstellar Institute should be visionary, futuristic and visually stimulating. One example for such a building would be the use of a pyramid shaped structure, a symbol of permanence and the need for long term planning in enduring programmes. It would be constructed of glass with layers of solar panels to supply the electrical energy for the building. Inside would be the building itself, constructed in stages analogous to the stages of a rocket. The ground floor level would contain the main conference hall, cafeteria, open air library, exhibition space and perhaps a Japanese garden. The higher levels would contain smaller conference rooms and offices for permanent and visiting residents working on the problems of interstellar flight. At the top of the building is the observational Skydome, shaped to represent an interstellar payload on top of each engine stage. The Skydome is maintained to low light levels, to allow visualization of the stars at night. Some moderate telescopes are permanently in place for the enjoyment of the visitors. The total floor area inside the pyramid is around 10,000 square meters, being 100 m on each side. The Institute would become the worlds leading centre for research into interstellar flight, promoting research excellence and stimulating scientific breakthroughs. The institute is to be a place of positive inspiration, where the best of humanity comes together to focus on solving the obstacles to the launch of the first interstellar mission.

On the very apex of the building is a high gain radio antenna for the sending and receiving of deep space signals for participation in some monitoring programs. On the first level is the main conference room capable of holding up to 300 people, using modern electronic visualization tools. On the second level is another, but smaller, conference room capable of holding up to 100 people. Small meeting rooms are included on the third and fourth level to hold up to 20 people. Each of the levels has a small balcony and railing which comes off of each office, providing for pleasant views over the arena and Japanese garden. In the middle of the third to fifth floor is a hollow opening allowing windows across the way. At the rear of the building (external to the pyramid) is a small observatory to be used for exoplanet observations to help determine the first astronomical mission target, focussed on stars within 20 light years. Entrance to this is enabled through the Japanese garden which is also a bird atrium. The overall design objective of the building is to inspire the designers, providing for a peaceful and relaxing atmosphere whilst being an innovative design using parallels with engineering technology from interstellar spacecraft designs.

References

[1] Anderson, P, “Tau Zero”, Orion Books, 1970.

[2] Niven, L & J.Pournelle, “The Mote in God’s Eye”, Simon & Schuster, 1974.

[3] Clarke, A.C, “Rendezvous with Rama”, Gollancz, 1973.

[4] Spencer, D.F et al., “Feasibility of Interstellar Travel”, Acta Astronautica, 9, pp.49-58, 1963. [5] Forward, R.L, “A Program for Interstellar Exploration”, JBIS, 29, pp.611-632, 1976.

[6] Gilster, P, “Centauri Dreams, Imagining & Planning Interstellar Exploration”, Springer, 2004.

[7] Matloff, G.L & E.Mallove, “The Starflight Handbook, A Pioneers Guide to Interstellar Travel”, Wiley, 1989.

[8] Long, K.F, “Fusion, Antimatter & the Space Drive: Charting a Path to the Stars”, JBIS, 62, pp.89-98.

[9] Long, K.F, “Deep Space Propulsion: The Roadmap to Interstellar Flight” (book), Springer, Publication Pending

2011.

[10] Ross, H.E, “The BIS Space Ship”, JBIS, 5, 1939.

[11] Parkinson, R, “Interplanetary, A History of the British Interplanetary Society”, BIS Publication, 2008.

[12] Shepherd, L.R, “Interstellar Flight”, JBIS, 11, 1952.

[13] Bond, A & A.R.Martin, “Project Daedalus – Final Report”, JBIS Special Supplement, 1978.

[14] Long K.F., Obousy R.K., Tziolas A.C, Mann A, Osborne R, Presby A, Fogg M, “Project Icarus: Son of Daedalus – Flying Closer to Another Star”, JBIS, Vol. 62 No. 11/12, pp. 403-416, Nov/Dec 2009.

[15] Dyson, F, “Interstellar Transport”, Physics Today, 68, 41-45, 1968.

[16] Cassenti, B.N, “A Comparison of Interstellar Propulsion Methods”, JBIS, 35, pp.116-124, 1982.

[17] Millis, M.G, “First Interstellar Missions, Considering Energy and Incessant Obsolescence”, JBIS, Publication Pending, 2011.

[18] Baxter, S, “Project Icarus: Three Roads to the Stars”, JBIS, Publication Pending, 2011.

[19] Long, K.F, “Project Icarus: The First Unmanned Interstellar Mission, Robotic Expansion & Technological Growth”, JBIS, Publication Pending, 2011.

[20] Dyson, G, “Project Orion – The Atomic Spaceship 1957-1965”, The Penguin Press, 2002.

[21] Long, K.F, R.K.Obousy & A.Hein, “Project Icarus: Optimization of Nuclear Fusion Propulsion for Interstellar Missions”, Acta Astronautica, 68, pp.1820-1829, 2011.

[22] Forward, R.L, “Starwisp: An Ultra-Light Interstellar Probe”, Journal of Spacecraft & Rockets, 22, pp.345-350, 1985.

[23] Landis, G.A, “Beamed Energy Propulsion for Practical Interstellar Flight”, JBIS, 52, 1999.

[24] Benford, G & J.Benford et al., “Power-Beaming Concepts for Future Deep Space Exploration”, JBIS, 59, 2006.

[25] Cassenti, B.N, “Design Considerations for Relativistic Antimatter Rockets”, JBIS, 35, pp.396-404.

[26] Bussard, R.W, “Galactic Matter and Interstellar Flight”, Acta Astronautica, 16, Fasc4, 1960.

[27] Alcubierre, A, “The Warp Drive: Hyper-Fast Travel within General Relativity”, Class.Quantum Grav, 11, L73-L77, 1994.

[28] Long, K.F, “The Status of the Warp Drive”, JBIS, 61, PP.347-352, 2008.

[29] Obousy, R .K & R.Cleaver, “Warp Drive: A New Approach”, JBIS, 61, pp.364-369, 2008.

[30] Millis, M, “Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Research Program”, NASA TM-107381, 1996.

[31] Millis, M & E.W.Davis, “Frontiers of Propulsion Science”, Progress in Astronautics & Aeronautics, 227, AIAA, 2009.

[32] Bond, A & A.R.Martin, “World Ships – An Assessment of the Engineering Feasibility”, JBIS, 37, 6, 1984.

[33] Martin, A.R, “World Ships – Concept, Cause, Cost, Construction & Colonization”, JBIS, 37, 6, 1984.

[34] Orth, C.D, “Parameter Studies for the VISTA Spacecraft Concept”, UCRL-JC-141513, 2000.

[35] Gaidos, G et al., “AIMStar: Antimatter Initiated Microfusion for Pre-cursor Interstellar Missions”, Acta Astronautica, 44, 2-4, pp.183-186, 1999.

[36] Beals, K.A et al., “Project LONGSHOT, An Unmanned Probe to Alpha Centauri”, N89-16904, 1988.

[37] Jaffe, L.D et al., “An Interstellar Precursor Mission”, JBIS, 33, pp.3-26, 1980.

[38] McNutt, R.L, Jr, “Interstellar Probe”, White Paper for US Heliophysics Decadal Survey, 2010.

[39] Long, K.F & R.Obousy, “Starships of the Future, The Challenge of Interstellar Flight”, Spaceflight, 53, 4, 2011.

[40] Maccone, C, “FOCAL – Probe to 550 or 1000 AU: A Status Review”, JBIS, 61, pp.310-314, 2008.

[41] Mankins, J.C, “Technology Readiness Levels”, A White Paper, NASA, 1995.

[42] Schmidt, GR & M.J.Patterson, “In-Space Propulsion Technologies for the Flexible Path Exploration Strategy”, Presented 61st IAC Prague, IAC-10.C4.6.2, 2010.

[43] Anderson, J.L, “Leaps of the Imagination: Interstellar Flight and the Horizon Mission Methodology”, JBIS, 49, pp.15-20, 1996.

[44] “Building on Success – Five year Plan”, Perimeter (PI) Institute for Theoretical Physics, 2009.

maybe it is better to think first about a manned probe to mars and other destination like the gas giants. We need to start with the first step before we are going doing the next. If we control first our own solar system it is likely that a interstellar trip will come soon after. For now interstellar travel is not

achievable.

Let me remind you of Lao Tzu’s maxim: “You accomplish the great task by a series of small acts.”

Interstellar flight will doubtless require a Solar System-wide infrastructure, and it may not happen for a long time. But the idea is to begin the thinking that will lead to practical ideas and result in workable designs. DARPA’s 100 Year Starship study is looking at how that kind of research effort can be put together and how the organization that develops it can function over long periods of time. It is only one study of many that will surely follow. Other organizations and other studies continue to pursue manned flight in our own system.

It is unclear to me what activities the institute is researching that will lead to sustainable business income. There are hints of space systems that a government might want to pay for, but that is all I see. Is this a viable model given the stated vagaries of government policy, especially over a century?

Even just focusing on one propulsion technology – fusion – is the proposed funding level going to be useful compared to the funding of hardware for existing fusion programs?

Does the idea of a physical research institute even make sense in the C21st century with the cheap communications technology now available? Perhaps it would be better to have a much more modest HQ and use all funds for research distributed around the planet? (It would certainly make administration much easier for researchers located in a number of countries).

[BIS as an organization has fossilized somewhat too, as the letters page of “Spaceflight” indicate.]

If I might be so bold, I would advocate a different approach. Create a foundation that can fund research for vetted proposals. Proposals for ideas could be put forward on a Wiki and a body of experts could decide which ideas merit funding. Forget about a business oriented approach, simply ensure that the foundation has enough funds from investment returns.

As for what projects to fund, that should be decided by the foundation. Avoid duplicate effort – e.g. human longevity, AI’s, environmental life support.

My sense is that it is most likely the institute will look rather stodgy in just 50 years. Rather like rocket societies still dreaming of human spaceflight to the planets, while the world uses robotic hardware instead. In 50 years, we will probably know a lot more about our galactic neighborhood and the focus will be on direct “telescopic” observations and possibly extremely miniaturized interstellar probes. My thoughts are more along the line of “what capabilities can today’s rapidly flowering technologies offer and how might they transform our outlook for the institute’s goals? maybe the best way to find out is fund some really good SF writers, with the caliber of am A C Clarke”.

Dear Alex,

Thanks for your comments.

The only government connection to the Institute proposed is through the creation of a non-profit under charitable status and perhaps in the assistance of the intial start up where required. In general the Institute is to be independent from government control. So your first comment on the role of government is not relevant to the model proposed.

You are right to flag up vetted proposals, and that is in essence how the Technical Advisory Committee(s), or body of experts as you call it, would work, using similar models to those like NIAC and NASA BPP. This would be part of the grant award system that allows residents to visit, but work together on specific engineering problems.

Then, those designs will feed technology inventions which can be transferred accross to the profit arm.

That said, I like your alternative web model too.

My primary motivation for writing the report was to make DARPA think outside the box. No doubt they are receiving many proposals for how to spend that several hundred thoustand dollars. I wanted to do something different, make them think longer term.

As an academic, I see high value in the existence of an Interstellar Institute as a key mechanism for focussing efforts towards specific programme goals, whilst allowing for adequate free thinking in a creative and flexible structure.

The BIS is alive and well, but like all organizations it occasionally must renew itself. This has been its constant history, with a perfect balance between the professional/academic and the non-professional/academic. If it swings either way too far it will marginalize the other. I asert this duality is one reason it has survived for so long, precisely because it has always hovered in balance between these two extremes.

Kelvin

Kelvin Long wrote:

“How can the pace of interstellar research be accelerated so as to facilitate an earlier launch window?”

This is a Propulsion Physics problem and as such all spare funds should goto Research & Education. The organisation mentioned by Kelvin is too far off and requires a lot of money. Unless there’s a private billionare out there ready to make the donation and yearly contributions, don’t see it happening in today’s economic climate.

I was very dissapointed when they canned the Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Program at NASA, they could have at least kept it going for a meagre $1 million / year which is peanuts compared to their total yearly budget (regardless whether this was in line with their more short term goals). Back to DARPA, if they need guidance now on how to spend any spare cash on interstellar research, there are already excellent organisations with the experience that can assist (TZF and the BIS).

Cheers, Paul.

The SETI Institute spent tens of millions of dollars on their headquarters while forgetting to keep the ATA at Hat Creek funded. Now we have 42 radio telescopes languishing in hiberation rather than listening for signals from intelligent beings around other stars.

The lesson here should be obvious, but just in case:

Focus on the Ship, not the HQ or anything not directly important to the goal.

And yes, we should go to the stars. We don’t need the Moon or Mars for this goal.

I am an ordinary person who washed up on your shore with no foresight. Yes, we must listen to the stars, aim for the stars, and, let’s really dream: Let’s make the effort a function of the United Nations. I will be 100 years old in 2040 I think I feel like Jules Verne or Leonardo di Vinci, so much appreciation for science, such a short life to experience it.

The range and variety of potential approaches to reaching the stars truly amazes and generally intrigues me. Its always a pleasure to peruse this site.

As to Kelvin Long’s response to DARPA’s call for papers, its apparent that he has given a lot of thought to the whole process, including that of establishing a permanence, or continuity, to a means for reaching the stars; right down to the design of a physical structure capable of serving as a base and icon for the work of an Interstellar Institute …

I am reminded of Heinlein’s approach in “Time for the Stars”; the Long Range Foundation. It seems though that Dr. Long’s organization suffers from a malady which afflicts most large organizations; complexity. I would rather see a much simpler model sans so many departments. I suppose though that departments could ‘come and go’ depending on what is thought feasible and what is ruled out by the scientific method. Besides, the tendency to select the more probable and to eliminate the less likely to succeed should naturally limit how many arms the body grows.

One of the things which shall contribute to fostering motivations to reach for the stars is … science fiction. I dare say that everyone who visits and participates and is featured at this site has a love of science fiction, and will acknowledge its influence upon them.

I’m an unknown sojourner here, but if I ever complete my first novel, science fiction of course, I hope it will inspire many to look at the stars and to see suns. Time will tell. ‘Til then, I wish all here success.

How many nuclear physicists with an expertise in fusion energy are on the Icarus team?

Because if we can’t get a real fusion reactor to work on Earth after decades of trying with many millions of dollars invested, how do you expect to get one up in space to power a starship?

LOL @ the pyramid at the end. Becuase you need swanky HQ or else! Reminds me of all the Silicon Valley startups that boght aeron chairs and pool tables then folded.

@Tyler: If we can go to the stars you can bet we’ll need the moon and mars. If we cannot go there with ease and reliably do so then any interstellar effort is doomed to failure. Baby steps.

Kudo’s to Kelvin Long for his outstanding ideas concerning an Interstellar Institute for Aerospace Research (IIAR). Some of the details may be arguable, but in general an Interstellar Institute is exactly what is needed. A similar idea has been pioneered in the area of Aging Research with great success over the last 12 years, i.e The Buck Institute. After 12 years the Buck Institute now serves as a Global magnet for research on the Biology of Aging, and progress in this domain has been significantly accelerated since it was founded in 1999.

Kelvin also mentioned that the IIAR would not be created until 2020 which is the right time-line since by then we should have a decent idea if there is anything of interest around our nearest Interstellar neighbor Alpha Centuari. If something of interest is found such as a planet or moon in the habitable zone then Interstellar Travel suddenly becomes much more viable and less far out in time. It may even be possible in the 21st Century given the relative nearness of Alpha Centuari to Sol, and the fact that we might be able to take a Lilly Pad approach to getting to our closest neighbor. At that point having an IIAR to focus on not only a mission to Alpha Centauri but all of the precursor mission steps including the requisite Interplanetary Travel and Colonization and supporting Technology development would be ideal.

As for funding, if a mere $10 Billion was put in an investment trust circa 2020 to sustain the IIAR that should be enough to create a fine Interstellar Research/Precursor Mission Program over time with an initial focus on Technology Development and Concept exploration. So where might that “spare” $10 Billion come from? Surprisingly it could come from the U.S. Government if something of real interest was actually discovered around Alpha Centauri. Again we must not judge these things by today’s standards, but instead anticipate a better time when people of more vision may control things and there is a widely perceived compelling need. This could be as early as 2020.

Project Icarus fits nicely into this time-line since it predates the potential 2020 founding of the IIAR and is focused on “the how”. The real risk to all of this is if nothing of interest is found around Alpha Centauri or at least out to about 12 Lyrs. If that is the case then Interstellar Travel barring some sort of “new physics” becomes far less viable over the next couple of Centuries given the potential distances involved. At that point it would be neccessary to reasses, perhaps with a much scaled down and almost exclusive focus on Breakthrough Physics since we are not going anywhere soon. A trip to Alpha Centauri, especially one that is able to follow a Lilly Pad Strategy in many ways represents a greatly extended Interplanetary journey that would start with several 1000-2000 AU precursor missions perhaps followed by the establishment of a staging base on Pluto or even further out.

Glad you found my comment amusing, Ian. Because I am definitely not giving one thin dime to an organization that wants money up front for its fancy and “futuristic” headquarters while promising me some wonderful payback way down the road after I am long gone. Sounds just like most religions I know. HMMMMMM.

So tell me how a colony on Mars will get us to Alpha Centauri? And I want something concrete, not the usual NASA plaititudes which sound pretty but say nothing.

I also went and checked the Icarus web site to see who is actually on this team (and who elected them, btw?). I see a lot of white anglo-saxon males from western countries in all the top positions – no big surprise there. Now my question is:

Where are the poets? The historians? The biologists? Anyone with real political and business savy? And who’s providing the real cash and resources for all this?

We’ve already got plenty of white papers on starship designs. So when does someone start putting two pieces of metal together? Or do I get to see three more decades of talk, this time from a cushy corporate office that looks like a really cool pyramid?

@Kenneth Harmon

I do not see any deep reason why aging and star flight should have similar institutions. Aging research was not very well coordinated, but recent interest has grown with the rapidly increase in biological knowledge. We could know with a few decades at most whether any of the current ideas might work, and these ideas would be at the medical stage with possibly human clinical trials in progress. There is an industry already in place to capitalize on any work and a huge demand for results. None of these features is in place for a star ship program.

If anyone is going to invest $10bn for anything, aging research would have a far higher payoff with a faster result. You might even solve some of the human star flight issues on the way.

Dear all,

I am occasionally checking in to answer any questions. Firstly, I would like to clarify some points. The DARPA RFI was restricted in its length, so the full concept of the Institute, how it would work and the reasons for why it is needed were not fully explored in the report – there simply was not the page space. Additionally, the intention was not to provide a complete plan, especially since the costs were crude estimates. Instead it was to provide ‘a plan’ to allow for a structured discussion. Ultimately the details of 100 people or 1000 people, $100 million or $500 million, Pyramid or Cube, are not so relevant. It is the concept of an inspirational and useful Institute and the research that it facilitates that is more important. Now I will attempt to address some of the more constructive comments made by others and those comments relevant to the article.

Paul Titze: Regarding the institute being way off and a lot of money. You say all spare funds should go into research and education, but that is precisely what the insitute would do, conduct research, educate and communicate the vision/reasons for interstellar flight. If you make an attempt to cost an interstellar probe it is likely at the lower bound of $1 trillion and at worst several hundred trillion {try it, I have}. Hence the cost of an Institute, and its funding in this context, is peanuts. Meanwhile, the institute delivers core research developments, increases TRLs and results in patented technologies will help to progress the pace of science and technology generally, particularly in space, bootstrapping research being made by the institute – we get to the first launch sooner rather than later.

Dispatcher: Thank you for your comments. Regarding the complexity of the plan, its just ‘a plan’. The number of divisions and how the research is structured is in the details. In essence I deliberately set about describing a grander vision and then efficiency and common sense can kick in perhaps leading to a leaner model. I was intending to provoke the imagination with a visionary picture. If I had described only a modest skeleton model, I don’t believe it would achieve that objective so well. I completely agree with you that science ficiton is a funamental inspiration factor in interstellar research. I’m a big SF reader myself.

Kenneth Harmon: I like your ‘Lilly Pad Strategy’ phrase, nice. You got it, some of the ideas are arguable but thats the intention. I will also tell you that although I thought about these ideas sometime last year the report was put together in two days (which others can testify to) when DARPA kindly gave me permission to submit upon returning from vacation. With more time, what else is possible?

Now I want to propose something for the President of TZF to be taken up by all the members of Centauri Dreams. Why not have a competition? A competition to design a sensible interstellar institute to be constructed in the year 2020 that is economic, credible, serves the goal of achieving the first launch, and is consisent with the business model requirements as stated in the DARPA RFI. This could become an official TZF competition and no doubt others could better my brief effort.

Who dares take up the task for a TZF Interstellar Institute Challenge?

Kelvin

p.s although the official santioning of such a competition would have to be approved by the TZF President. I am merely proposing it here.

I think I’m starting to see Weyland-Yutani Corp. You’re going to have to fight some serious corruption potential while trying to earn 100 trillion. Plan carefully.

Would there be any benifit to setting up separate entities, to foster competition and spread power? Maybe an Omni Consumer Products for habitats, Cyberdyne Systems for the AI/robotics and Yoyodyne Propulsion Systems? Aperture Science Laboratories, Black Mesa and Union Aerospace Corporation can work on teleportaion. :)

Based on my understanding of the various Technological Readiness Levels, I would propose, say, 30% engineering, 30% research, 30% theoretical and 10% administrative/ public outreach. There’s already an abundance of papers that have been written that few people read (and fewer fully comprehend), outlining everything with fantastic equations but which get absolutely no traction with research, let alone engineering. To distinguish it from existing agencies and add to credibility, the aesthetic and bureaucratic fluff could be trimmed down.

Regarding the title, I’m not sure “Interstellar” and “Aerospace” really fit together; they refer to separate fields. My idea has been simply “IPP” : “Institute for Propulsion Physics” (in the distinguished vein of “Institute for Advanced Theoretical Physics”).

I agree that we don’t need to go to Mars or the Moon as preliminary steps. I don’t see the point. The inner planets are no more hospitable than LEO, and are immensely more difficult to reach. That’s why we haven’t gone to Mars already; the cost/benefit ratio is way out of wack. It would be like building a shopping mall on the North Pole. The only preliminary step to interstellar missions is SSTO, to facilitate experimentation and engineering in space. Having the patent on an SSTO vehicle (one that could get the cost of payloads per pound down to something ordinary people could afford) would be all that is necessary for all the funding needs of any organization well into into the foreseeable future, be it government, business or non-profit.

Regarding life extension, it does indeed go hand in hand with space migration just as IT / AI does. Robert Anton Wilson gave a lecture on this way back in 1980- he called it SMILE, although the more appropriate term is SMAILE (space migration, artificial intelligence, life extension). These constitute the three main tenets of transhumanism, similar to the Holy Trinity. But the life extension wouldn’t be to keep people alive for extended deep space missions; it’s to keep researchers on earth alive long enough to master a thing like warp drive engineering, which could have a centuries-long learning curve, and mastery can only really be attained on an individual level. Furthermore, engineers may be the only people who would desire immortality- engineering is perhaps the only field with a perpetual linear progression.

The notion of an interstellar institute was brought up years ago and still resides on the TZF “about” pages. At that time, the tactic was to wait until enough progress and revenues had been made, and the key pioneers identified, before launching into this ‘invitational’ institute. As much as institutes can be focal points to spur progress, they can also end up limiting participation and serving themselves more than their mission (a common pitfall as organization mature).

It is my personal feeling that investing energy toward an interstellar institute now is premature and likely to draw energies out of the other projects we are trying to get up and running.

In the meantime, the tactic that I am employing for interim ‘new’ research and education is to try and get graduate students, wherever they are, to pick thesis topics aligned with any of the unsolved, next-step issues of star flight; from; “What’s out there?” “How to get there?” and “What does this mean for humanity?” If they do, I might be able to pair them up with practitioner experts to advise them. Only one such thesis is underway at present, at the USAF Inst of Technology. I am attempting to establish collaborations with other universities so that we can jointly apply for future grant funding for both the student and to help pay for the services of our practitioners. Right now, that is one of the Tau Zero activities I’m working on behind the scenes. I feel it will spur greater progress and broaden opportunities for less cost and effort.

Wish me luck!

Marc Millis wrote:

“It is my personal feeling that investing energy toward an interstellar institute now is premature and likely to draw energies out of the other projects we are trying to get up and running.”

Maybe DARPA would like to setup a modest yearly fund to help with the costs of running projects or even scholarships through TZF? This would result in real benefits now towards interstellar research and motivate new students to pursue their studies in this area since the funds are available if they are successful. Papers can then be submitted to http://arXiv.org and http://viXra.org and reviewed here by our interstellar journalist, Centauri Dreams readers and TZF folks for further comment.

Cheers, Paul.

Establishing an Interstellar Institute will be a steadier step to support the mission. However, the first interstellar mission will be economically affordable and technically feasible only with development of relativistic space drives. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sgAwyr5Udzw

Here is a very positive thought about Project Icarus: If the team comes up with a way for controlled, contained fusion power, not only will they have literally helped to save our growing technological civilization,they will also make enough money from this to build twenty Icaruses!

Alas, this approach has not worked for the countless teams who have tried just that, very hard and with tons of money, over the past 50 years or so….

I am afraid I have to side with Tyler Durden, here: Why would we think that we can be more successful? Because we read more science fiction?

Eniac wrote:

“Why would we think that we can be more successful?”

Because all the interstellar propulsion options presented so far are based on current known Physics ie they could work but demand such an engineering feet that it makes all of them unpractical options for the stellar distances involved, they are also simply too slow (from solar sails to antimatter, forget about warp drives/wormholes these are dead ends). We haven’t even considered yet how to get all this hardware into orbit from Earth’s surface.

There are many lingering unknowns in the Standard Model of Physics, to be able to pursue practical interstellar flight (if at all possible), one has to pursue Breakthrough Propulsion Physics which could result in a more succesful approach to the intestellar flight problem. If the BPP option fails, our chances of interstellar flight are very slim because in 200 years time things may not look so good for us on Earth ie we are running out of time (where society flourishes) due do many factors (overpopulation, resources etc). Why 200 years? See Marc’s paper:

http://arxiv.org/abs/1101.1066

Cheers, Paul Titze.

Tyler and Eniac wrote:

“Why would we think that we can be more successful?”

Propulsion fusion differs from terrestrial fusion in that you don’t need to contain the reaction; in fact, you specifically want to eject material from the back of the engine to produce thrust, and the super-heated reaction products themselves can readily serve this purpose. Recall that we’ve had terrestrial fusion on this planet since the 1950’s — the issue is just sustaining and controlling the reaction. No, I think the biggest challenge for propulsion fusion isn’t in making the reaction happen, but in sufficiently miniaturizing the necessary equipment.

– Robert

But if we can build a fusion reactor in space (and yes I know what that will involve, thank you), and I mean in actual space, then size should not be such an issue.

I say the bigger the starship/probe, the better chance of its survival, to say nothing of being able to carry more equipment and such. You can dispense with lots of little probes at a target star system, but they will need to be protected by something big from radiation, dust, gas, and who knows what else.

@Paul Titze

With respect to this reference:

http://arxiv.org/abs/1101.1066

The estimate of when starflight becomes possible is for a world government reaching some level of energy availability. The energy fraction allocated to starflight is by society is estimated to be 1.3^{-6} (not unreasonable). I wonder how this might look for a privately owned corporation (which probably can allocate a substantially larger portion of its wealth, e.g. when the founder decides to retire)

Peter

Peter: Unless star flight will be powered somehow from the grid (unlikely), there is really no relationship between the power we use for housekeeping and that which our starship uses for flight. The latter could be a thousand times the former. What matters is the cost of fuel and engine, that better be just a small fraction of our GDP.

Eniac: obviously, energy is here being used as a surrogate for cost. Unless you think that in a century or two’s time power will be too cheap to meter, a starship will only be able to use a small fraction of the energy budget of the society which builds it. Fuel costs money.

Tyler Durden: you ask how will a colony on Mars help us get to Alpha Centauri? Let me ask you what you would have thought of someone in England at the time of Elizabeth I responding to Sir Walter Raleigh’s proposal to set up colonies in America with the claim that we did not need to colonise America in order to fly to the Moon.

In the first place, the justification for the more distant goal is the same as that for the nearer one, and in the second place, the further goal is only remotely achievable by a society which has already long since reached the nearer one. The most concrete aspect of this is population size: the enormous energy cost of starflight demands a greatly expanded economy, therefore a greatly expanded population, therefore a Solar-System scale civilisation. Its enormous development cost also requires that cost to be spread widely over society – in other words, if you build one special engine for an interstellar probe or starship it will be immensely expensive and unreliable (a Space Shuttle of an engine); if you adapt your engine from high-energy propulsion systems already in large-scale commercial use in the Solar System, then the main burden of the development cost has been borne for you by mass markets (a Rolls Royce of an engine).

The factor which is missing from most of this flurry of excitement about this 100 year initiative is that, while a small robotic probe is just about conceivable as a product of Earth alone, for any sustained or systematic interstellar exploration, particularly if manned vehicles are involved, the indispensable precondition is extraterrestrial colonisation (sci-fi speculations about magical “breakthrough” propulsion systems aside). Manned vehicles require in addition at least a century’s experience with orbiting space colonies (otherwise how do you demonstrate long-term sustainable human life-support in space?).

The key point at present is that, as growth on Earth levels off, extraterrestrial population and economic growth must begin to rise. This scenario has to be our entry point into the public consciousness. Until society has put this process into gear, starships will remain a dream.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

Hi, the use of the word ‘Aerospace’ in the name ‘Interstellar Institute for Aerospace Research’ was chosen as a nod to the importance of spin-off technological developments to impact the aviation/astronautics industry but also to acknowledge that the remit of the institute would also have to include some ‘aero’space reserach, e.g. gas giant mining using balloons and ramjets/scramjets, SSTO to orbit to assemble large space structures, design of sub-probes to enter the atmosphere of other worlds. It is in this context that I chose the word ‘Aerospace’. But equally it could be called the ‘Interstellar Institute for Astronautics Research’.

kelvin

Carl Sagan discusses Orion, Daedalus, and the Bussard Ramjet on his Cosmos series, complete with large blueprints:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yak-KFI-jKA&feature=related

In a recent Programme on Discovery Channel entitled “Evacuate Earth!”, reference was made to the not inconsiderable task of maintaining a focussed sense of mission among a population in a closed environment, most of whom would never see their goal- leaving the future to unborn descendants.

Many might feel tempted to give up, or wander aimlessly among the stars, losing their readiness for the rigours of landing on a strange world and begetting a new civilisation .

Complete hedonism and nihilism is clearly a threat, while an authoritarian military style regime could degenerate, as on Earth, into deadly dictatorship presided over by psychopaths – the usual result ).

One approach might be a religious type of approach, but not sectarian. It is well known that in World War 2, faith allowed people ( the Jews in Nazi ruled Europe for instance ) to procreate when any rational consideration would have precluded it. Nevertheless, procreation occurred within the shadow of death, and helped to populate and lead the Jewish State of Israel.

A sense of quasi religious “mission” or “election” could help to maintain cohesiveness as the wanderers travelled towards their new “Promised Land!”

Another example was rather idealistically shown in theHG Wells film “Things to Come!” when a ravaged world was pacified by a group of airmen- “The Freemasonry of the Air” as Cabal termed it.

A version of Freemasonry itself would engender cohesiveness and a sense of mission- in their words , it exists to make good men better, and greatly furthers education and comradeship.

Perhaps the world ship could be the ultimate Masonic Lodge, with the addition of the Ladies. There are after all, Ladies’ Lodges today!

The key will, I propose, be to start with good people as well as technicians.