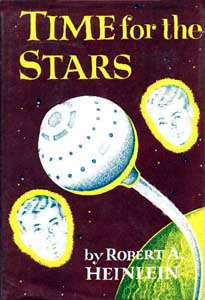

Anyone who looks back on Robert Heinlein’s ‘juvenile’ novels, twelve books written for young adults between 1947 and 1958, as inspiration for his current work gets my attention. I loved every one of those novels, particularly Citizen of the Galaxy (1957) and Starman Jones (1953), but David Neyland says it was Time for the Stars (1956) that got him thinking about the 100 Year Starship Study. If you’ve been keeping up with Centauri Dreams, you know that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which handles cutting-edge research and development for the US military, is putting on a starship symposium this fall in Orlando, FL.

This follows up on the earlier DARPA Request for Information and will lead to the award of $500,000 or so in seed money to an organization that can best pursue the study’s goals. Neyland, who is director of DARPA’s Tactical Technology Office, has been explaining what the study is all about to newspapers like the Los Angeles Times, which ran a story on it on August 6. Heinlein’s books came up naturally in the interview, for it turns out that Neyland was quite a science fiction reader in his youth and found Time for the Stars a natural fit with his mission to inspire a new generation of scientists and engineers with the dream of starflight. The key to the linkage is Heinlein’s use of a foundation that would facilitate long-term thinking and planning.

Thus the Long Range Foundation, which in the novel creates technologies that take generations to deliver, but eventually benefit not a single government or corporation but the entire species. In the book, twins Tom and Pat Bartlett turn out to have telepathic talents that allow them to communicate with each other instantaneously, and other twins display the same gift. It’s a useful trait because it appears that using such twins is the only way to stay in touch with a far-ranging starship. Thus a representative of the Long Range Foundation comes to visit the twins and their father, where we learn about the background of the organization, as told by Tom Bartlett:

Its coat of arms reads: “Bread Cast Upon the Waters,” and its charter is headed: “Dedicated to the Welfare of Our Descendants.” The charter goes on with a lot of lawyers’ fog but the way the directors have interpreted it has been to spend money only on things that no government and no other corporation would touch. It wasn’t enough for a proposed project to be interesting to science or socially desirable; it also had to be so horribly expensive that no one else would touch it and the prospective results had to lie so far in the future that it could not be justified to taxpayers or shareholders. To make the LRF directors light up with enthusiasm you had to suggest something that cost a billion or more and probably wouldn’t show results for ten generations, if ever … something like how to control the weather (they’re working on that) or where does your lap go when you stand up.

It turns out, of course, that a foundation like this pays off in a big way, having developed a number of exploratory starships called ‘torchships’ that can reach a substantial percentage of the speed of light, more than enough for time dilation to kick in. And as the young Bartlett reflects upon a school paper he has written on it, he realizes that the Long Range Foundation (LRF) has been having the desired effect for some time:

Mr. McKeefe had told us to estimate the influence, if any, of LRF on the technology “yeast-form” growth curve; either I should have flunked the course or LRF had kept the curve from leveling off early in the 21st century – I mean to say, the “cultural inheritance,” the accumulation of knowledge and wealth that keeps us from being savages, had increased greatly as a result of the tax-free status of such non-profit research corporations. I didn’t dream up that opinion; there are figures to prove it. What would have happened if the tribal elders had forced Ugh to hunt with the rest of the tribe instead of staying home and whittling out the first wheel while the idea was bright in his mind?

Neyland credits Heinlein, then, with the notion that inspired the 100 Year Starship Study, but he also points to Jules Verne, whose From the Earth to the Moon appeared in 1865. The point of such books isn’t that they were accurate in terms of the actual technologies involved — Verne shot his crew off to the Moon from a giant cannon in ways that would have mashed them to a pulp — but that they inspired people to think about the larger topic of traveling on such a momentous journey. And Neyland noticed that it was just over 100 years later that Apollo 11 set down at the Sea of Tranquility. Like Verne, then, we may not have all the answers about starflight (to say the least) but a starship study may inspire people to ask the right questions and think big.

At a press conference in June, Neyland spoke to journalists about the study (see this Centauri Dreams story on the event), noting that in the Request for Information period that produced over 150 responses, some people had misconstrued the study’s intent. DARPA has no plans to build a starship, in other words, but to develop understanding about how research into such long range matters can be conducted, and to encourage the inevitable spinoffs as such studies are pursued. Hence the planned award to a single group that can become the locus of interstellar studies over a long time period (and if none is deemed suitable, DARPA won’t disburse the money). Here’s how he describes the study’s true goals, as told to the Times:

A lot of folks think that we’re asking for somebody to come in with a plan on how to build a starship. That’s actually the wrong answer. What we’re looking for is an intuitive understanding of the process of inspiring research and development that comes up with tangible products.

“Products” doesn’t mean physical products, but might be a new computer algorithm, a new kind of physics, a new set of mathematics, a new philosophical or religious construct, a new way of growing grain hydroponically. The organization needs to have the gestalt of how to inspire that kind of research.

Will we, in the same hundred year stretch that separated Verne from Apollo, develop the technologies we need for an actual trip between the stars? It’s an energizing thought, but from our perspective today we have no way of knowing. Nonetheless, the idea of creating an organization that can shepherd various approaches to a starship — and this is a multi-disciplinary undertaking that ranges from physics to biology to sociology and more — is one that surely captures the imagination. What spinoffs it might generate along the way are open to conjecture. Unlike so much in today’s world, the project is inherently long-term, looks out well beyond current lifetimes, and asks what will produce results not just for us but for future generations as well.

The agenda for the 100 Year Starship Study symposium is now available online [but see Jim Benford’s comment below]. And if Heinlein’s Time for the Stars is what led David Neyland to this, maybe it’s time for me to re-read it. “We know the questions to ask, but we don’t know all the questions to ask,” Neyland told the Times. “We can hypothesize where we want to get to, but it’s a pretty broad target that we’re aiming for.” A broad target indeed, and it’s high time we began gathering the resources that, if interstellar flight one day proves not just possible but practical, will eventually lead us to a mission.

Hi Paul,

Great post,was it that long ago I read all that stuff?. Do not forget

‘Have Space Suit will Travel’. Such musing bring up a memory trace

of a story by Heinlein were the two main characters were living on the

moon in a dome working on StarShip Designs and Plans. I can not recall

the title,does that ring a bell?

The whole idea of long term planning,thinking is spot on ,just look at the willful

avoidance of many of todays problems. Richard Posner in this great book

‘Catastrophe: Risk and Response’ looks into some of the issues regarding

long term planning thinking and such. He spends a lot of time looking at the NEO questions. The book is a few years old but still trenchant none the less.

Best regards,

Mark

Paul, please forgive my divergent comment – but it does relate to DARPA and the idea of seeking out new concepts that can get our species off the planet. I don’t think anyone can be happy with the country’s present financial state – and the terrible employment picture. This is relevant to DARPA because a strong military is only possible with a strong economy, so this should be a major concern. Space development will also suffer if the economy does not improve. Here is my main suggestion: We know that our country finances black projects, so how about financing a black market in scientific and next century infrastructure. Instead of printing money and giving money to the banks to loan out; the money is provided off balance sheet by DARPA to projects that will improve our economic picture. This idea may sound farfetched, but is it anymore so than giving tax breaks to companies for outsourcing American jobs? Our government and financial system is man-made. If it doesn’t work, like Roosevelt during the Great Depression believed, we need to try bold creative ideas until one works.

Thanks for the reminder of this SF novel, I know I am showing my age, but “Time for the Stars” was a favorite of mine as a teenager in high school in the late 50’s. It really is not that dated and is still a good read today. Another classic about ‘realistic” interstellar travel and long range planning was Arthur C. Clarkes “Songs of Distant Earth” Both of these are great reads for people interested in this subject.

Time for the Stars is a great read (note: you will want to rush through it, but take your time), and is best understood as a retelling of Magellan’s tragic and, yes, terrifying voyage of discovery (see the amazon page here for an excellant contemporary history, Over the Edge of the World: http://www.amazon.com/Over-Edge-World-Terrifying-Circumnavigation/dp/006093638X/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1313428721&sr=1-1), the percentage of ships lost and the duration (in subjective time) being about the same. As a fun exercise, you may want to read the two books together.

The novel is one of my all time favorites. It is psychologically astute, filled with realistic characters and fantastic ideas, and I believe it is arguably Heinlein’s finest juvenile. Every aspect of the book is integrated perfectly. I’ve read it about twenty times and it is time to read it again. Not everyone would agree, of course. Certainly it is among his most misunderstood novels.

On a personal note, I wrote a paper and actually got to present it for the Heinlein Society (2007) on how the Long-Range Foundation and Edward de Bono’s ideas on creativity (his generative logics such as parallel thinking in particular) were a natural fit. Heinlein is in fact a precursor to de Bono (this is made very clear in his novel, almost as good as TFTS, Tunnel in the Sky). Unfortunately, the paper sailed right over the audience’s head and the notion went nowhere. Almost certainly my fault. Maybe someday others will glom onto the ideas and run with them.

My feeling is that long range planning of the kind your talking about isn’t compatible with our current form of government and culture. Democracy and consumer capitalism have very short time horizons and are subject to chaotic popular demands which make long-term projects almost impossible. The Chinese are demonstrating an alternative way to run a modern state, and they seem poised to rocket past the moribund democracies. So I would like to suggest that another form of government, perhaps techno-fascism or some kind of theocratic rule by a “cosmic religion,” would be more effective in implementing hundred-year plans to reach the stars. Space enthusiasts can create foundations and make grand plans all day long, but without real power they are just producing science fiction.

Thanks for the synchronicity of your entry! I presently am ‘re’-reading “To Sail Beyond The Sunset’, another Heinlein novel. This one was written in 1987 – rather later in his auspicious career! In this novel he invents another longevity foundation called, ‘The Howard Foundation”, whose purpose is to genetically select individuals who have the right genes for long life and encourage them to marry similar individuals. Living beyond 100 years may not seem to be something you’d want to do with a ailing body? So his premise to select out the healthy sounds reasonable? Not eugenics, but if done without a political or personal profit for an agenda?

Heinlein apparently turned somewhat scatological in his later years? There is a LOT of sex in this read and some of it not up to social standards. Incest does not interest me and reading about it again does nothing for me. His take is rather benign on that subject, in that while in his eighties he seems to have had a tendency to moderate his morals? Never the less, an interesting read too!

For people interested in Heinlein and the evolution of his thought, there is no better source than Robert Heinlein, In Dialogue with His Century: http://www.amazon.com/Robert-Heinlein-Dialogue-1907-1948-Learning/dp/0765319624/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1313445460&sr=1-1). This is the first volume which takes his life up to 1948. The second volume is in work and my guess is will be completed next year.

Note: Heinlein was very experimental in all aspects of his life and work (the Howard Foundation btw was first written about by Heinlein in the 1940s). I don’t know if recommending the biography as strongly as I do takes us too far afield, but I simply find the man and his thinking fascinating. If you are not into it, then realize he began a descent as a writer in the last 20 years of his life (beginning with the ghastly I Will Fear No Evil), and much of what he wrote then can only be understood in terms of the very complex structure of his life story, which includes his health and sexuality. I believe his works before that time stand on their own and you don’t have to know much if anything about his background to enjoy them (though it may help).

star ships, 100 year or otherwise, are not built by elves or even robots for now. people build star ships in factories and they are assembled in earth orbit.

scientists think up equations and engineers figure out how to implement those ideas. on paper and even in science fiction these plans and machines seem to be without flaw. everything works fine. but in the real world things tend to go wrong.

people who are not scientists and engineers have different motives. take investment banking. 100 yss will be developed when investment bankers see the profitability in it. say as a life boat to bail out of a dying planet.

would a deprived underclass build such a ship for the elite to escape?

Defense Secretary Leon Panetta has called for cuts to social security before cuts to the pentagon budget. is that what learned men and women of science and engineering want?

untold trillions of dollars are spent on defense. no one knows where much of it goes. surely there is enough already to build a fleet of star ships. most ends up in the pockets of people who just want money.

already we have legions of scientists and engineers. and what does the defense industry produce? grounded f-22 and f-35’s mostly. VTOL osprey.

350 million dollars spent on ships that went right into the scrap heap without any service. billion dollar battle wagons with bad engines always in dry dock.

yes! a fleet of star ships and full employment with high wages and living pensions and medical care for the folks who work in the factories manufacturing star ships.

or am i dumb? is DARPA’s plans only for a special elite? what about the rest of us? cut me in on a big piece of 100 yss pie.

i read mostly a. c. clarke and i. asimov. i read some heinlien. downward towards the earth rings a bell. very dark and disturbing. he describes many mishaps to space farers in his novels, often gruesome.

what if the recent riots in england happen in the usa when social security is cut or gasoline and food isnt delivered? how will that effect the planning of a 100 yss? how about corruption at the highest levels of government? how about low wages and a polluted environment? i think those things will have as large an impact on building a 100 yss just as much as the scientific and engineering hurdles.

I Like Richards idea. We need to increase aggregate demand and the giant corporations can’t or won’t.

Spending on new technologies for the future creates good jobs NOW instead of the Fed playing casino games with the banks/wall street

Paul Krugman thought it would take an alien invasion to turn around the economy . I would posit building our starship faster could do the same thing…

I really like seeing Project Icarus leading the schedule.

— Actually, that quote shows the first nibbles of the Brain Eater on Heinlein’s frontal lobes. “Tax cuts will save CIVILIZATION! There’ll be FIGURES to PROVE IT!”

Heinlein got increasingly grumpy about taxes from c. 1950 onwards, as his income rose steadily higher. (Keep in mind that back in the 1950s, the top tax brackets were 75% and 90%. Dark times indeed.) Within another decade or so he’d have Wise Old Characters pronouncing, in the voice of absolute authority, that there was NOTHING WORSE OR MORE EVIL than forcing a man to pay taxes.

Anyway. _Time for the Stars_ is a fine book in many respects, but it also has some problems. For starters, it gets relativity wrong — utterly wrong. You wouldn’t have a slow twin and a fast twin. Each would perceive the other as slow. Before long, each would be talking to a twin living in the “past” — leading to communication through time and causality violations. That’s how relativity works, folks, and its why instantaneous communication is just as problematic as FTL.

And it shows astonishingly little thinking about the implications of technologies. For one example, even in 1954 it would have been pretty clear that launching a fusion-exhaust starship from a planet’s surface was a terrible idea. (Multiple reasons. Do I really need to spell them out?) Also, this is a future that has clean, cheap controllable fusion, where a nonprofit can build a dozen starships capable of accelerating at 1g forever. Yet it’s a future where food is rationed.

As for the Patterson bio, it’s… problematic. It’s likely to be the only detailed Heinlein bio for many years, and possibly ever. So it’s what we have. But it has issues. Patterson is a huge fan, which is inevitable because the Heinlein estate was never going to let a non-fan biographer near their stuff. So it’s not exactly an unbiased account. Also, Patterson is not a particularly careful and meticulous scholar. (Thorough, yes. But that’s a different thing.)

Doug M.

David, I’m glad to see that someone read my comment and approved of it. We know that the space program and DARPA have been instrumental in developing new technologies that have greatly stimulated our economy (internet, computers). Imagine if DARPA had two hundred billion dollars to not only develop but finance next generation infrastructure projects with an eye towards optimal employment gains. Why should money be doled out to the banks who then dole it out to the corporations who then sit on it, waiting for the economy to improve? If the money were off-budget, we’d really be getting a bargain for our investment. Why should we allow ourselves to be dominated by human financial constructs that are not effective in creating full employment? Perhaps the government of China would be more sympathetic to these arguments. Many party members with their engineering background and their 5 year plans might not only be more receptive to this way of thinking, they might already be doing it. Stupidity is to continue doing the same thing and expecting a different result.

This is a good choice of direction. Most of our problems — personal and collective — originate with an inability to ask what questions need to be asked in the light of the information available.

Mark Phelps, the Heinlein story you are thinking of is “The Menace From Earth.” The protagonist and her boyfriend are working on the blueprints for a starship that uses “Davis Mechanics” (which was a bogus scientific theory concocted to explain the long since discredited “Dean Drive”)

I see at the Next Big Thing that GNP and innovation growth have stagnated in our country. Today’s high unemployment can also be seen as a further sign of our national decay. Go to the following address:

http://nextbigfuture.com/2011/08/world-transformed-and-need-for-faster.htm

and note that DARPA’s role in bankrolling innovative technology is highlighted. Perhaps DARPA could do even more if instructed to massively upgrade our nation’s infrastructure and GNP with some black, off-the-books money. (It’s all paper play money anyway.)

A few corrections:

1) “David Neyland says it was Time for the Stars (1956) that got him thinking about the 100 Year Starship Study.” I was at the kickoff meeting in January. Someone brought up the quote from Time for the Stars and Dave said he didn’t remember it. But it does make a good story for the press.

2) “The agenda for the 100 Year Starship Study symposium is now available online.” I suspect this is a far-from-final agenda. Junior staffers put this Agenda together and the DARPA staff immediately put it online, unwisely. The Chairs of the tracks have not approved it. Therefore there will be revisions. In particular, the two tracks I’ve organized, the two left columns, will be put back into the sequence I gave them 3 weeks ago. Therefore, those in these sessions should look for revised versions of the aganda, and perhaps for other sessions as well.

Jim, I saw your message on the agenda in the Icarus message you sent out — I’ve added a note to this effect in the article text and will link to the final version when it’s available.

Pardon my cynicism, but IMHO, I very much doubt that any society based on western democracy will ever go to the stars, or even beyond low Earth orbit ever again. We are collectively suffering from a massive failure of will & nerve, and effectively have a self imposed horizon on planning which extends as far as the next election (for Government spending) or the next takeover/merger (for Private sector spending). When I compare the massive projects and big thinking of my parents generation, with the small mindedness, petty politics and “can’t do” ethos of today, I feel that our great days as a civilisation are already 30 or more years behind us.

I therefore contend that if we’re going to the stars, it will be from the base of a society as different to us as we are to ancient Egypt. The Voyager probes, Apollo missions and maybe some more recent efforts are likely to be forever the high point of Western civilisation. Famous early footsteps, but not the true start of our journey to the stars.

I am thus of the opinion that any long range foundation aiming for the stars must be primarily concerned with sociology, economics & politics. It must be aiming for a way of bringing about that long term thinking, stable, sustainable society that has the will & means to aim for the stars. That society is clearly not us as we are today.

Colin Weaver, I put it to you that it is not the West, but the way we use it that is at fault. If we were in a high tech version of the Roman world, our generals would know to bribe the Augurs, but I suspect that we in the scientific community would not. In the modern world, politicians have fulltime spin-doctors, we advocates of scientific projects do not.

RE Sith Master Sean’s idea that a techno-fascism or similar monolithic society might be needed to support such long range projects:

The problem with such systems is that they are too top-down to allow the *absolutely essential* accurate feedback that is the basis of all science and engineering.

China has the political will to finance the maglev trains and manned space program, yes. But they build them with technology dreamed up and developed by others, in cultures that encourage the young punks to tell the learned professors to go fly a kite, whenever they have half an excuse.

The great leaps of technology usually come when an open society is under threat (like WW2) – and sometimes when it sees huge economic opportunities (like the dotcom boom), and occasionally when its competitive pride is on the line (like the 60’s space program).

While economic opportunities are coming into play in low-orbit and interplanetary space, only the pride factor is likely to come into play in interstellar travel in the 100-year range. This should not be written off. The fact that Americans laid claim to reaching the moon -a half century+ before anyone else- has created advantages in an astounding variety of arenas.

Why scientists should read science fiction

By Hannah Waters | September 29, 2011 |

Republished with scant edits from the previous iteration of Culturing Science on July 20, 2010. A great blog post about fiction inspiring science by Uta Frith reminded me of this old friend. Hat tip to Princess Ojiaku.

I didn’t really grow up reading science fiction. Sure, I was (and am) completely obsessed with some fantasy novels (e.g. Lord of the Rings), but never made the leap to becoming a true sci-fi enthusiast.

It wasn’t until I started studying science more fully that I developed an interest in speculative science fiction. Many of the stories deal with technology taking over civilization – but embedded within this framework is a great deal of excitement, along with some deserved anxiety.

Full article here:

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/culturing-science/2011/09/29/why-scientists-should-read-science-fiction/