The first conference devoted solely to worldships takes place today in London at the headquarters of the British Interplanetary Society. It seemed a good time to check in with Gregory Matloff, a man I described when writing Centauri Dreams (the book) as the ‘renaissance man of interstellar studies.’ Perhaps best known for his continuing work on solar sails, Matloff’s interests have nonetheless ranged widely. He brought deep space propulsion to a wide audience in his book The Starflight Handbook (1989), which covers the full spectrum of interstellar options, but for over three decades has continued to produce scientific papers investigating issues ranging from laser ramjets to beamed microwave missions. A recent interest has been the expansion of the human biosphere into space, as discussed in books like Paradise Regained: The Regreening of Earth (Springer, 2009) and the soon to be published Biosphere Extension: Solar System Resources for the Earth, written with C Bangs. These last titles indicate that the interest in worldships Matloff first cultivated in papers for JBIS in the early 1980s continues to burn bright, as the following will confirm.

PG: Greg, I know you have a paper slated for the worldship conference that the British Interplanetary Society is holding today in London even though you couldn’t be there in person. And I know you’ve also been drafted by the Benfords to give a talk at the 100 Year Starship conference coming up in Orlando in October. When I first surveyed the field for my Centauri Dreams book back in 2004, I learned you were one of the early voices on this intriguing concept, the idea that a spacecraft might become a vast habitat capable of carrying thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of people between the stars.

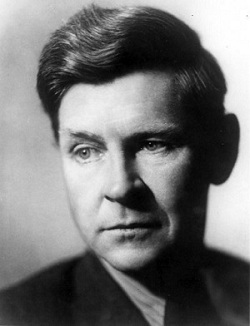

GM: I was one of the early scientific writers who addressed the idea. The concept itself goes back to the 1930s and even earlier. Worldships are mentioned in a philosophical essay by J. D. Bernal, The World the Flesh and the Devil (1929). There is also an absolutely wonderful science fiction novel by Olaf Stapledon called Starmaker (1937). He not only talks about world ships but also implies that stars themselves are conscious.

PG: The 1930s were an extraordinarily productive period both for science and science fiction.

GM: Extremely productive.There was a literary group at Oxford University that has become justly famous. C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien took part in this, and Stapledon was often discussed. I would have loved to have been there to have heard these guys kicking their ideas around in the era before World War II, a time when they all knew what was coming. It must have been fabulous. The worldship idea then disappears, although Tsiolkovsky mentions it when talking about space greenhouses and things like that. He doesn’t really develop it, and nobody touches it to my knowledge until the 1970s.

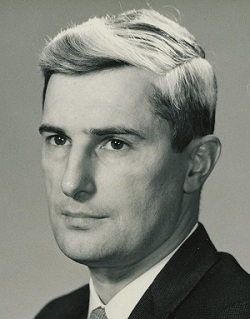

Then came Dandridge Cole, before Gerard O’Neill comes onto the scene, talking about ‘macrolife’ and the possibility of hollowing out asteroids to create workable habitats. Gerard O’Neill himself is important because he takes the idea and makes it concrete. O’Neill had major people working for him, such as Brian O’Leary, who was an astronaut, and Thomas Heppenheimer, who becomes a well known space writer. Eric Drexler would became the co-founder of the field of nanotechnology. So these are very bright folks, and they worked with O’Neill on the space colonies. O’Neill somewhere in there quotes Stapledon, and Arthur Clarke refers to him as a true science fiction visionary. He’s referring to Starmaker.

Image: Dandridge Cole, who coined the term ‘macrolife’ to refer to human colonies in space and their evolution. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

PG: Are worldships a theme in science fiction today?

GM: I found in the last 30 years maybe a couple of pieces, including Greg Benford and David Brin with Heart of the Comet (1986). People are hollowing out Halley’s comet and making it livable. The book also speculates about uploading of the human essence into a computer and things like that. What seems to have happened in science fiction in the last 20 or 30 years is to me many steps back. We’ve gone in the direction of military science fiction on the one hand and fantasy on the other. I go in looking for science fiction and would like to buy something but it’s very hard for me to find something in a Barnes & Noble that I’d like to buy. That to me is sort of depressing.

Looking Inward: Prospects and Consequences

PG: This seems to be a long way from the intense vision of the 1930s.

GM: Exactly. Now it is possible that we might be doing inward exploration rather than outward exploration. A recent book we purchased is How the Hippies Saved Physics, by David Kaiser (2011). The book talks about folks who started to apply quantum mechanics to human consciousness. It turns out C and I knew one of them fairly well, Evan Harris Walker, who died a few years ago. He was very much involved in this approach. I think what happened is that inward exploration, probably because of the 70s, had replaced outward exploration in many peoples’ minds. There may be some sense to it because people in the 70s thought they could do exploration by taking a pill or something similar. Later on learning how to do it by meditation and yoga comes to seem easier than funding a trillion dollar project to launch a few people into deep space.

PG: Just as setting up computerized VR is easier. Maybe we’re still going in the same direction.

GM: Yes, I think so. In fact, about two years ago, in October of 2009, C and I went to a meeting of singularity people. We were guests of Greg Benford. It was very interesting to hear these brilliant mathematicians talking about a virtual reality and folding human consciousness into it. Its a seductive thought. Now, is it more seductive than SETI? Is it more seductive than actually going out and colonizing new worlds or spreading the biosphere beyond the Earth — I don’t know!

I run into this with students all the time. Some of them are much more interested in inner exploration than outer exploration, and I don’t have any answers for this, except that I do hope that we also extend the biosphere, because I think it should be a goal of technological consciousness. It’s something we can do and it’s something we should do rather than having everybody just living in a little box. You and I may turn out to be in the minority on this.

Image: Olaf Stapledon, whose vision became a focal point for C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, and influenced Lewis’ subsequent science fiction, which was partly written in response to Stapledon’s ideas.

Near-Term Drivers for a Worldship

PG: Could be, but I suppose the worldship concept is sort of the ultimate extension of the expansion of the biosphere. Because these are gigantic vessels. Just how big are they?

GM: There are various estimates of the size of a worldship. If we’re talking about an interstellar ark, something that is like living in a submarine, it’s something that may be the size of a submarine. This is Edward Gilfillan in the 1970s

. The Outsiders are doing exactly that, traveling in worldships, and they consider it nearly low class to travel at a speed greater than one or two percent of the speed of light.PG: I love that because it’s such a reversal of conventional thinking. Everyone is trying to go as fast as possible, and at the same time we all have the sense of short-term horizons. Here we’re saying, what’s your rush? And if we don’t get there in this generation, maybe we can in the next, or maybe in a hundred generations.

GM: Exactly. And that’s what they do. As I recall, the reason that terrestrials developed hyperdrive in these stories is that it’s a trade item for the Outsiders. They don’t care about things like that, but they’re trading for the things they want. Sure, hyperdrive is an interesting technique; it allows you to go fast if you want, but to us the voyage is the more important thing.

PG: I love the Niven stories of that era. Now you remind me I must go back and do some re-reading of those tales.

GM: Sure! They’re fabulous. And the more I think about it, the more significant science fiction is to science. Visionary science fiction is very, very important. People like Clarke, Asimov, Stapledon. Asimov does speculate that the early migrations from Earth are by worldships. He calls them interstellar arks.

PG: In which books?

GM: In the Foundation series, he does mention that the ruins of some of these arks are discovered around planets orbiting various stars, including one or two planets in the Alpha Centauri system, and they’re not sure where they come from. One of the speculations is that they come from Sol originally, 50,000 years ago. But the records have been lost.

The Worldship and the Sail

PG: Greg, although you are not going to London for the worldship conference, I know a paper of yours will be presented there on the question of using a sail for propusion. Tell us more about that.

GM: What has happened with the sail is that we know that solar sails are the only propulsion system for interstellar travel that people have suggested to date that can be used for acceleration, deceleration and cosmic ray shielding enroute. Because you simply wind it around the habitat. So it’s a tri-use device, which none of the others methods have. And what I do is I review a lot of the literature including acceleration and deceleration and I talk about the fact that right now the most investigated sail material is beryllium. People at NASA hate that.

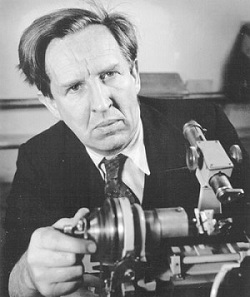

Image: John Desmond Bernal, a British physicist and crystallographer whose The World, The Flesh & The Devil (1929) investigated a human presence in worldships and discussed the possibilities of solar sailing long before it became fodder for scientific papers.

Les Johnson [NASA MSFC] was at a conference in Aosta, I forget if that’s the one you were at, and when I described the work of a beryllium sail, he did a wonderful imitation of Indiana Jones and said, “Oh no, why did it have to be beryllium?” Because he’s making a very good point. If NASA wishes to build an Oort Cloud explorer which is going to be a small scale 2000 year ark — and in fifty or sixty years they could build this to demonstrate a prototype interstellar spacecraft and also to do exploration of the Oort Cloud — right now beryllium is their only candidate for the sail, but beryllium is also very toxic. Les was saying if we do this, we’re going to have to deal with huge losses and tremendous safety issues. I understood his point, but technology is changing very rapidly.

There are things like carbon nanotubes and more recently graphene. These are interesting because they could have thickness measured in nanometers. Maybe a couple of molecules thick. They would have a finite either reflectivity or absorptivity, which means even though they are extremely low in mass, they are very strong. They’re going to be pushed by photons. So you could certainly imagine lowering the interstellar transit time with the sail to something like a millennium, maybe even lower than that. I don’t know. I would hesitate to say that we’ve discovered everything.

PG: I actually remember Les saying that about beryllium two years ago in Aosta. But you’re saying that these possibilities are going to be significantly thinner than anything we might do with beryllium?

GM: I think they’ll be both thinner and stronger than what we’re doing with beryllium, and they may not be toxic to work with. Right now they are amazingly expensive. If you were going to come up with enough graphene to cover a postage stamp, it would cost something like a hundred million dollars. So to build a real starship would bankrupt the planet. Even if we paid it out over a century. So the graphene price has to come down by many orders of magnitude.

One person at the Aosta congress did suggest that this isn’t impossible because this is what happened with aluminum. Aluminum when it first became recognized as a possibly significant commercial metal, probably a century and a half ago, was remarkably expensive. But a number of commercial processes were developed and the price began to drop dramatically. And as it dropped, people found more and more applications, driving the price down still further.

PG: What sort of mission configuration would you foresee? We can talk about a close solar pass, but our colonists are not in any great rush anyway, are they?

GM: They’re not. If you are using graphene, you might even be able to start with something like Earth orbit to get there in a thousand years. Because it’s very, very thin. A lot depends upon how its reflectivity or absorptivity varies with temperature. We really don’t know much about this material at this point to any great depth. I’m going to be talking about this also in Orlando, and presenting some of the numbers one of the guys presented at Aosta. But it’s not something you can get your hand around at this point. It’s still a brand new material that’s extremely difficult to work with. It’s very expensive, and there are only a handful of labs on the planet that can fabricate the stuff. So right now it’s a scientific material but not yet an engineering material.

Life Within the Colossus

But I do think if you’re going to extrapolate how to engineer a worldship, you would think about something that is a small version of an O’Neill colony. It maybe has the dimensions of a small skyscraper, maybe a hundred meters high, twenty meters across. That’s the payload. The payload might mass something like 107 kilograms if it’s using a 2000 year beryllium sail, an inflatable sail, maybe the sail size is 600-700 kilometers.

PG: Huge sociological issues come into play when we’re talking about millennial voyages.

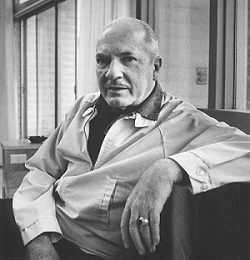

GM: Our crew would have to deal with interesting sociological matters. How do we become a society that stays intact for that long? And it was interesting that Arthur C. Clarke was not an optimist about the sociology. He was an optimist about the technology. In one of the Rama novels [in the series that began with Rendezvous with Rama, 1972], Rama was an alien worldship that comes to the solar system and aliens invite the terrestrials to fly a ship out and colonize it and live there with some of the aliens. Ultimately a few thousand terrestrials take advantage of this, and they have to decide how to live on this worldship. They decide to have a society with a lot of sports events, so they build stadiums for these. What happens is one of the major team players says I can take this place over. And he develops a cadre of fellows to work with him who enslave or massacre the other males and the various women become sex slaves.

He develops a fascist state with him on top. And what happens is one of the women revolts and she is able to get in contact with the worldship intelligence, which is the supreme intelligence of the universe, so she has a good deal of help, and because of this there is a very successful revolution. But OK. In any event, what Clarke is presenting there is pessimism about sociology and so was Heinlein in ‘Universe’/’Common Sense’ in the early 1940s. He has a worldship going between Earth and Centauri and the society falls apart. So basically all the people assume this is their universe. These two stories became the novel Orphans of the Sky, published as such in 1963.

It’s a brilliant story and of course the protagonists break in somehow to the holy of holies, the control room, they see what the stars are, they learn about the universe and they just happen to be passing through a solar system which is probably the Centauri system and there happens to be a livable planet. Somehow the shuttlecraft is operable by non-experts and they are able to elicit a landing. OK, Heinlein was playing the odds to have a happy ending to the thing, but the sociology is going to be a major factor because we haven’t had small human communities isolated for that long. There have been a couple of experiments and their results aren’t that good.

One of the experiments is the Vikings in Vinland. And when you look at that, the Vikings come and settle a small colony in Vinland [the account is told in the Saga of the Greenlanders]. One of the women is Freydis, the daughter of Erik the Red, who decides it’s too cold in the winter. She wants to be warmer, and why must she have only one male to snuggle up with? So she slaughters all her sisters and she has all the men now. This is in a small colony and they have nothing to do with the surrounding people, who they call Skraelings, the native Americans. So that’s an example maybe of a space colony gone wrong and becoming a tragedy.

Image: Robert Heinlein was one of a number of science fiction writers of his time who investigated the potential — and the problems — of worldships. Credit: The Heinlein Trust.

PG: On the other hand, I suppose one potential cause for optimism would be that a large enough worldship is going to have quite a large population, so perhaps that kind of diversity might play to survival. But I think the larger point you make is exactly in tune with the upcoming starship conference, mainly that while we usually think of interstellar ideas in terms of the propulsion that would get a probe there, the field actually demands a multidisciplinary approach.

GM: Very true. You make a good point about having a large population and I think O’Neill speculates that for a space habitat to be self-sufficient, it needs a population of something approaching a hundred thousand. Certainly tens of thousands of people. Then you have to say, what are they all going to do? If you have a large population like this, what will they do between stars? You have to design a ship in such a way that maybe the ship is never completely finished. Maybe the ecology always needs adjustment for it to work. Or maybe you have a second ship launched with materials to be mined as needed. Going out to the second ship and mining that becomes one of the periodical heroic episodes for this enclosed culture. Because look at the fact that we do seem to need heroes, in war or hopefully more frequently in sports. Look at the number of sports the industrialized and developed world practices today, and that’s to keep sane. That is largely to take the people who would be actual warriors and give them a role in society so they don’t have to go around other countries hacking off peoples’ heads.

A Multidisciplinary Study

PG: So all these things point us in the direction of the need to assess sociology, philosophy, history, to look at how humans have done in other settings when they’re in remote places.

GM: Yes. I would love to know the early history of the Minoan colonies in places like what is now Gaza. Or when the Minoan/Mycenaean peoples colonized Miletus in Asia Minor. Miletus becomes the parent for Russia, for many of the eastern European countries, because many of the people from there starting in about 1000 BC begin to build colony cities around the Black Sea area. I would love to know how many of these succeeded, how many failed, what the interaction was. Did they war with each other, did they war with the indigenous populations? I’m likewise fascinated with the early story of the Etruscans. They were obviously strongly influenced by the Minoan/Mycenaean civilization, but how did they do this? Were they a direct colony? We’ll probably never know. Or were they indigenous people who traded to try to build their own cities?

PG: You mentioned the possibility of having a second ship that might have resources the first could exploit. Is there an argument to be made that human nature says in any case a second ship is a good idea because you need to have a neighbor, a potential other, out there with you?

GM: It’s a possibility, that you might send instead of one ship a small fleet, particularly if you’re using something like a solar sail or a photon sail or maybe even an electric sail — you don’t have to pay for the propulsion. And in either case like this, conceivably, you could send as many colonies or habitats as wanted to go. That may offer something like this, because they could trade with each other, maybe they could have political or athletic contests with each other, maybe even there could be some form of highly ritualized warfare. I know that warfare among some of the native American population was initially very ritualized in just such a fashion. So we might be able to find all types of possible models in history and pre-history to go with.

PG: This discussion harkens back to that wonderful 1983 conference Interstellar Migration and the Human Experience, where you did have a very multidisciplinary group coming together to look at this kind of question, relating the topic to events like the settlement of the Pacific islands.

GM: Yes, that’s exactly what Ben Finney did. Unfortunately, I was not at that conference [held at Los Alamos in 1983], and always wish I had been. I’ve never met Ben Finney and would like to. I’m hoping he’s at the 100 Year Starship conference.

PG: Same here. I’m looking forward to seeing you at that conference, Greg, and want to thank you for your time this evening. As always, it has been a pleasure to talk to you.

Addendum: Kelvin Long sends via his smartphone this shot of the lunching worldship conference crew at the BIS headquarters where, as I post this (1600 UTC), the event should be just wrapping up.

I’ve been pretty firmly convinced for some time that worldships are how we’re going to leave our solar system, gradually, centuries from now. It’s going to be an organic process as we simply expand from orbit, with a growing population living and working in space and among the asteroids. Not unlike the Rotor habitat in Asimov’s _Nemesis_, sooner or later, one or another reasonably self-sufficient O’Neill colony society is simply going to mount a propulsion system and just slowly leave.

We’ll be a long time getting to that state, though. Centuries, certainly.

What about those individuals in the worldships who actually want to explore the stars within their lifetime and not just live in deep space playing sports or mining? In my mind, worldships don’t make sense in terms of the exploration of the galaxy. There will always be easier, cheaper, lower energy ways of doing actual space exploration. If worldships are actually the parallel of the role of today’s cruise ships, then at least a cruise ship docks at an interesting port every couple of days. I am inclined to view worldships as being a fiction-based fantasy which distracts from actual interstellar exploration. It is OK as a fantasy but should be recognized as such and distinguished from more realistic proposals for actual interstellar exploration. But that’s just my perspective.

I’m not sure if were up to worldships when our economy and Europe’s are in tatters. Twenty million Americans are presently out of work, and many fear that things that will only get worse. A globalist economic policy that does not ensure a reasonable wage and no working plan for international environmental standards is presently the norm. Even the idea of worldships as well as serious space exploration will become laughable if these trends continue. Also, how seriously can we consider a large, social groups in space if we can’t maintain ones on earth. Also, a weakening America economy is undercutting our military. It truly is time to think and act outside the box. For example, imagine how far we could advance if DARPA was given 200 billion dollars (off the books) to generate 21st century infrastructure and jobs. Unfortunately, most of our politicians are jokes – certainly compared to top Chinese government officials, who are frequently highly educated in engineering and science. DARPA or some significant nonprofit should begin work on how to humaform the earth. Develop a 100 year plan for star travel is certainly praiseworthy, but a functioning world economy is the horse that will (or won’t) be pulling this cart.

Istvan

you are maybe right. We can wait to someone create a

warp drive/wormhole. Ore we can already think about other ways. If FTL is really

impossible. I do not know it is. We can cry about it. Ore we can find other ways like this. We need more people that are thinking about those subjects. That we can search for the best possible way to leave this solar system and travel to the stars. We can also wait to the United Federation of Planets come to us to give us the secret of the warp drive, but that will never happen lol

Johnhunt, the world ship idea is about colonizing the stars, not exploration.

2000 years to Alpha Centauri means an average speed of around 620km/s to stop at the destination, total delta V of 1240km/s, a fusion drive with an exhaust velocity of 10,000km/s could achieve that with a propellant mass ratio of 1.13 (a one billion tonne world ship carries 130 million tonnes of propellant), that sounds feasible, especially if the shear size of the engines allowed less exotic fuels could be used.

Another possibility is to travel even more slowly, colonizing not the next star, but the next Oort cloud object, at such a speed the relative movement of the stars might contribute more to colonizing the galaxy than the ship engines.

I’m afraid worldships are about living in space, not even about colonizing in the usual sense. Once a society has been living on a worldship for a generation or two, they won’t give a fig for planets.

Andrew W makes the point of worldships moving from Oort Cloud object to Oort Cloud object, and I completely agree. Worldships will just gradually filter outward, using the by-then centuries-old skills of mining asteroids.

We will absolutely not be building worldships in the next decade, or in the next century, but we should hope that in a few decades we will finally be making the necessary steps to learn the space-based construction and mining skills our descendants will need.

We’ve had the technology to move these needed astronautics fields forward for about fifty years now, and have made only the tiniest of baby steps working with objects like Mir and the ISS. We’ve certainly proven in that time that our manned space programs need destinations or they wander off without focus. All our destinations, be they surface bases or orbital habitats, are things we must build ourselves. The sooner we start, the better, and also the sooner some of these destinations can start generating an economic return, the sooner the “why bother with space at all?” questions similar to Richard’s line of argument can likewise be satisfied.

I was delighted to read that Greg Matloff thought bootstrapping Bigelow’s modules is a viable plan for a world/colony ship. It just seems like such an obvious immediate path to me. And he also pointed out the problem with making grandiose long term plans: by the time you get to implement them, times and technology have changed so much that your original design is obsolete. Who foresaw that space tourism might be leading the charge?

However, Paul, I am somewhat mystified that you didn’t follow up with the obvious question: What are consequences of going down the zero-G path?

I was also intrigued by the topic of using magnetism as shielding. I have been kicking around the idea that a strong magnetic field would not only make a good shield but could be used for locomotion in zero-G. A person could wear a belt that generated its own field that worked against the habitat field, and should be useful even for station keeping. If the habitat field has an AC component, it could induce current flow into the belt. In other words, you could move around like you were a smart hysteresis synchronous motor. Does anyone have any thoughts on this?

A worldship that is home to 100,000 people for generations that is a measly 1 to 5 km long is asking for social failure. This ship needs to be 10 – 15 km long and about at wide to sustain 100,000 people for even a trip of several years, much less for generations.

Manhattan as an example for what the population density would be like may be great for a voyage of a smaller time frame, but over generations, it is just too congested. I’m willing to bet that most of you reading this are accustomed to having to lock your house up and your car, to watch closely any passerby when you’re out alone and a grundle of other habits that come of living in a large population center. I live in a place where I don’t lock my doors and haven’t for 25 years. Passers-by generally say hi, and sometimes we stop to have good conversations, even if we’re total strangers.

My point is… in a place as small as 1-5 km with 100K population is bound to generate a failed social structure sooner or later. People really do need green space, not something cramped and monotonous. Not some holographic toy. We need something new and exciting. The sports and ritualized war (Babylon 5 aliens, the Drazi, had such a thing) is definitely a must have, but not all of us like those things. Some of us like nature, solitude, adventure. Some of us need animals, so there needs to be plenty of room for them, not just cats, dogs and parakeets.

So… you may think this will up the cost of this ship, but hey, if we’re gonna dream, let’s dream big. I mean really big. Let’s not have a measely 1 or 2 ships travling along together, let’s have an armada of 5 -10 of these behemoths and keep the population density low – 100K people per ship – to conerve on the resources of food, energy, water, blah-blah-blah. There must be large farms for growing food – which means, there need to be room for chickens, cows, pigs, etc. and horses because they’re fun. Recreation is extremely important. It’s as important as having a job to do. There must be a place for mountains with skiing and other kinds of mountain sports and let’s include the animals we would find in them – bears, cougars, coyotes, deer, moose … well, maybe not the predators. Let’s have jungles and deserts and watery habitats. I don’t think oceans would work here, but lakes with fish and beaches and boats would work.

Your current design concepts of these worldships is conceived like an engineer would conceive it – all practical, functional and works like a charm. Nothing wrong with that, but over the generations, there would be social failure, which would result in mission failure. You need to look more carefully at how people really live. Get out of the city and the burbs and look how people live in less populated places. Look at the social cohesiveness vs crime rate. You’ll find in those places, most people are the kind of people who would make the voyage a success because they’ve been doing it for generations already.

Mark Presco writes:

I see no zero-G path available, I’m afraid. Early experiments in extending zero-G habitats to larger living quarters will surely prove the point that any long-term colony, much less a worldship on an interstellar mission, will have to provide a living space that keeps humans healthy. Putting enough spin on such a ship to approximate planet-side gravity seems a natural development.

This seemed suspiciously dramatized to me, so I looked it up. Indeed, when you read the (presumably better researched) Wikipedia article on it, there is no support there for this curious “too cold in winter” interpretation of the story. For one, the women Freydis executes are not her sisters, nor rivals for male warmth. Rather, they are captives from two partner ships after their male crew have all been killed on her orders. The reason Freydis gets her own hands dirty at all is because her men refused to kill the women, out of male pride.

Of course, this may still be viewed as a cautionary tale for would-be colonists, but the motivation here was competition for personal wealth, power and fame back at home. None of these seem like viable motivations for world-ship inhabitants to kill each other, simply because there isn’t any sufficiently relevant “back home”.

Of course we will have to keep humans healthy. We don’t need experiments to tell us that. But what is the evidence that you cannot keep humans healthy in zero G? This you imply, but do not actually state or support with evidence.

“Healthy” here should mean longer/better lives, not strong bones and muscles. The latter will most likely be impaired by zero G, but this may not be a problem at all if you live there. Indeed, I would consider it more plausible that zero G extends life because of the reduced stress on bones and muscles.

A better understood analogy: Modern civilized life makes you weak and pale by sharply reducing physical exertion and exposure to the elements. However, this has not led to a decrease in health, quite the contrary. Life expectancy has gone up about two-fold, due in part to those very same factors.

You all seem to be ignoring the fact that by the time the technology exists to build world ships, human biology and culture will have morphed into something that makes the whole idea absurd. This is the main problem with the classic SF visions of Asimov, Clarke, Niven, etc. that have obviously inspired you: they just project present-day homo sapiens centuries into the future and give them better machines. But look around: the technologies that are advancing the fastest are biotech and info tech, which means that we’re probably going to be modifying ourselves in interesting ways long before we make a serious push into space. At some point in the not very distant future it seems likely that our virtual environments will become so rich and interesting that no one will want to leave the Matrix for the cold, empty desert of space.

As much as I love the romantic 20th century visions of space exploration, the more rational part of me thinks that it’s probably just a beautiful fantasy, and in reality humanity (and post-humanity) is going to explore inner space, not outer space.

Mark Presco, we allocate 25 sq m of office space per worker in the West. In space surely 10 would be sufficient, and given 3 eight hour shifts per day, we would only need afford 3 meters of rotating space to each passenger. Is it then possible that to give each passenger sufficient time at higher gravity to satisfy physiological requirements we could “link” a much smaller rotating module built to higher specifications to the worldship, or would this create even more problems?

I have dire worries for the spherical O’Neil colony implied in this article that was a kilometre wide, but only an (American?) billion pounds. This calculates to only about 150 kg per square metre of surface area. O’Neil himself said that several metres of soil (I think he suggested ten) was needed to stop secondaries from cosmic rays. This would equate to about 30,000 kilograms per sq m. Could this be a plug for the old (British) definition of billion?

Eniac writes:

I was thinking about long-term bone loss in weightless conditions, which I know can be mitigated to some extent but I thought the problem had not been solved. Maybe I’m wrong on this — any readers know of recent research?

The problem with colonization is that the target worlds are unsuitable. Either they are barren, lifeless rocks needing perhaps millions of years to terraform, or living planets with an unknown and potentially lethal biology. Who in their right mind is going to step off a safe earth based living world ship for one of these destinations, except for terraformed planets in the very distant future? Maybe you send down machines to clear areas and build safe domes, but is this really better than just using asteroidal rocks and comets to build more space habitats? O’Neill’s logic was clear, humans will live in space in large, engineered habitats, not on planetary surfaces.

But let’s consider that a suitable world exists, which can support humans immediately. How would we go? I would posit that a “world ship” need be nothing more than an ark carrying the information for human genomes and a way to create the biology for gestating babies and machines to take care of them until adolescent. While there is skepticism that artificial general AI will ever be good enough to allow machine surrogate parents, perhaps simpler machines and teaching devices will be enough.

The usual demand is that people are educated to high tech levels at the destination in order to run a high tech colony. But if instead you can create enough smarts for a hunter-gatherer/farming technology, then all you need do is push the societies to more high tech civilization over generations. Our present culture is just 250 years (10 generations) post the industrial revolution, and just 5000 years (200 generations) or so since the agricultural revolution in the fertile crescent. And that is will the rise and fall and empires and the slow bootstrapping of knowledge. That time may be compressible.

Bottom line. Send small, fast, seed ships instead. Use local resources for constructing human and earth life at the destination. Bootstrap advanced civilization using stored information and self constructing machines and replicators.

Let’s not have a measely 1 or 2 ships travling along together, let’s have an armada of 5 -10 of these behemoths and keep the population density low – 100K people per ship – to conerve on the resources of food, energy, water, blah-blah-blah.

At least a million people is a semi-decent sized city. At 100k, we’re moving towards towns. Now, there’s nothing wrong with towns of that size, assuming they don’t blindly sign contracts with MFP Financial Services, but anyone who lives in one will admit they sometimes need to visit a real city or even Toronto for the goods and services not available out in the marches.

Anyone here actually grow up in a small town or rural setting [1]? Anyone here want to imagine how much fun it would to grow up in a small town knowing that you could never, ever, ever leave it, not even for a day trip? That’s one of the problems with arkships; the people who board it get considerably more freedom of choice than their descendents will.

1: I grew up on a farm but also spent years in in a major city, in a small town, and medium sized towns and spent a year in an isolated fishing village.

I have had no return comments regarding how the state of our economy is imperiling science. It seems quaint to discuss far-fetched plans when the axe will soon be coming down. Presently, congress is looking at severely cutting the National Nuclear Security Administration, which has been effective in retrieving nuclear materials. Congress is also giving DARPA a much closer look – not only at its administrator, but also the 100 year starship plan (which may do for a quick extinction). We need a new Manhattan plan to get our economy working and a new political party that will get it done.

@The Cosmist

As a technologist working professionally in the field of virtual entertainment myself, I find your point extremely relevant. However, I am forced to disagree on two grounds –

(1) Humans have a long history of fairly extreme conservatism, and this is reflected yet again in modern dialogues about GM foods and organisms. I expect we will see in the next century continuing squeamishness regarding modifying ourselves. As a result, just as I expect progress toward worldships to be gradual, I think overcoming cultural resistances to cyborgs and gene-modifications to also be very slow.

(2) The economics of inner space seem to move us closer to a zero-sum game, and I think that is absolutely deadly dangerous to us all, culturally. I think it’s a route to a future with much higher potential for dystopia. Our modern (and dangerously creaky) world economic system requires expansion and frontier, if only for continuing access to tangible resources, and that should drive us into space (though for much lesser projects and goals than worldships!) sooner rather than later.

Please note that I don’t disagree entirely – I agree there are strong forces moving us in exactly the directions you postulate. I think danger lies that way for us as a world society and while we can and should reap benefits from bio and info technologies, subsuming ourselves with them is ultimately a fatal choice.

I don’t know that it would be a good idea for generation-ship fans to read SF about generation ships, given that the usual sequence of events involves a social collapse somewhere in mid-journey. Sometimes this works out ok (as in “Proxima Centauri” [1]) but often you end up with situations like the ones in ORPHANS OF THE SKY or the third EXILES book, where a slowly degrading tin can filled with barbarians careens into deepest interstellar space.

1: The bit right at the end, where almost everyone is killed or taken as fodder for intelligent, carnivorous plants, could have worked out better but until then the mission was going as well as could be hoped. Except for the mutiny.

Admittedly, it’s not quite a generation ship but the story is one of the sources for the common tropes seen in generation ship stories.

More on Murray Leinster’s story “Proxima Centauri” here:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=192

the third EXILES book, where a slowly degrading tin can filled with barbarians careens into deepest interstellar space.

Mind you, the mission could have ended in success had the crew decided at Alpha Centauri to use their genetic engineering to create humans that could live on the life-bearing but hostile to terrestrial life world they found there and given that they were not sure they’d survive the trip to Alpha C, committing to a trip at least twice as long to the nearest K or better star [1] was a big risk.

1: Unless they headed back to the Sun to see if the political situation had changed, which seems like a better bet than Epsilon Indi.

James Davis Nicoll August 18, 2011 at 10:48: “Anyone here actually grow up in a small town or rural setting [1]? Anyone here want to imagine how much fun it would to grow up in a small town knowing that you could never, ever, ever leave it, not even for a day trip? That’s one of the problems with arkships; the people who board it get considerably more freedom of choice than their descendents will.”

I think the most similar communities on Earth would be the inhabitants of small islands, Aitutaki for example has a population of just 2000, and a very low crime rate (having said that their bank, apparently secured by one padlock, was recently burgled, the culprits are suspected to be visitors to the island).

So yes, I think small communities can be stable, remember that most humans have lived their lives in small communities, having said that, I think that it’s important to have small communities living in a bigger world, so maybe a dozen distinct habitats, so people could go somewhere else on holiday, and the local rugby team would have a competition to play in.

Having said that I also have to agree with The Cosmist that people in (say) 500 years are not likely to be as similar to us as we are to our ancestors of 500 years ago.

Having said that, how the hell did I manage to say “having said that” three times in one comment?

@Richard

I first invite you to note that I partially responded to your remarks in one of my earlier comments. I don’t think anyone is deliberately ignoring your points and concerns. More directly, I do agree with much that you have to say, but I have two not-entirely-compatible lines of thought with which to respond.

First of all, I advocate bootstrapping our space industries as rapidly as possible, as I think much of our economic turmoil is due to the rapidly closing frontier, which our society and economy, even our civilization, still all require in order to continue in their current forms. I assert that without this frontier (and I’m assuming space is or should be it or I wouldn’t be posting here), our world civilization will become something other than what it presently is, possibly dystopian and inward-focused along the lines of The Cosmist’s remarks. As an American, which you also apparently are, of course I’d like to see our nation maintain some semblance of leadership in the exploitation of space, but frankly that doesn’t matter for humanity as long as somebody acts, and at the end of the day that’s what’s more important to me. DARPA crash projects aside, I’ll be perfectly happy, thrilled even, to see some commercial space enterprises push the astronautics on the cheap in the next two decades, shake the trees, and make things happen. I do personally want to see progress in what’s left of my lifetime.

However, moving over to the other line of response, our current troubles in America are a blip, I think. Unpleasant for us to watch and live through, to be sure, but in the long view a blip. We’re still an immature sub-250-year-old nation and we still need to learn some things about focus, or at least present generations do. I very strongly agree with your remark that we need a new political party – some of our problems are that our ‘system’ is designed to lock out any but the existing two, and likewise the political process is designed to favor radicalism rather than cooperation, a recipe for gradual decay if ever there was one. All that is beside the point, though, because whether we develop capable astronautics and engineering technologies in the next thirty years, or in a thirty-year block late in the 2100’s after we get over ourselves and grow up as a world, the worldships we’re supposedly talking about are still at least two or three hundred years away, even if most of the necessary core technologies are already at hand right now.

Though a latecomer to this discussion and risking repeating others with my usual rant on this topic, I do agree with Alex Tolley that slow and very large space colonies (world ships, O’Neill colonies) are most probably not the way to reach and colonize the stars, for about the same reason that oil rigs are not the way to cross the ocean and colonize another continent ;-)

The comparison with cities like Manhattan and even medium sized towns is totally inappropriate, because such cities and towns have never been self-supporting in any way, they constantly need large supplies from very large surrounding areas.

But more importantly, very large and technically complex artificial space colonies with an active and rather large human population are subject to great risks of failure, both internal (technical) and, though to a much lesser extent in interstellar space, due to external factors.

This is partly due to the relatively small size of even very large space colonies, partly due to its (technical) complexity and partly due to its lack of intrinsic stability. More or less continuous maintenance and possibly even (partial) replacement is needed.

This is something which can be achieved within a solar system, but not on a very long interstellar journey.

The risk of total catastrophe that such a space colony is exposed to is comparable to the extinction risk of small islands, which is greater with decreasing island size (so-called stochastic extinction).

I believe that the way to reach the stars is relatively (very) fast and preferably either with a purely technical payload or a human crew in a state of suspended animation (‘hibernation’).

Therefore, I think that key research required to reach the nearest stars this and coming centuries will be in the fields of advanced (fusion, laser, …) propulsion, human life extension, and suspended animation.

———-

More or less continuous maintenance and possibly even (partial) replacement is needed.

———-

Replacement and maintenance would probably be much less than what would be expected. For one thing there would be less wear and tear.

– Much of the infrastructure could be build where there is no major temperature changes. No need to build to deal with both the extremes of winter ice and summer heat.

– No need to build to deal with hurricane force winds.

– No need to build to deal with flooding.

– Depending on design of the ship the 1-g gravity all buildings on earth must deal with.

– Earthquakes.

…

A space habitat would probably be less expensive to maintain than building on earth would be.

Impacts would not be a problem. Anything small can be deflected, anything large can be evaded.

Radiation, well that is what the hull is for.

———-

The risk of total catastrophe that such a space colony is exposed to is comparable to the extinction risk of small islands, which is greater with decreasing island size (so-called stochastic extinction).

———-

Is not relevant comparison. A worldship would be a planned environment where the people would be planning for centuries in advance and have stockpiles to deal with emergencies. They would know exactly how many tons of such and such a material they got and how much they need. It would not be a random environment subjected to the randomness of an earth based environment and biosphere.

Also resupply may not be out the question for a worldship. Traveling at a slow speed they may very well send smaller ships out to mine comets they are by passing.

First , this has been an outstanding discussion, second a few practical points

1) I have been doing some calculations on the loss of diversity in a star ship population and found that using some simple and available technologies for freezing sperm and fertilized ova, the diversity can be kept quite high for many generations with a small populations, provided the frozen samples are good for two to three (overlapping) generations.

2) a lot of our resources are spent educating our young for a third of their life span and caring for our old for about 20 % of our life span leaves only half our lives as productive. With life extension we can improve this ratio a lot! we can also reduce the risk of losing technical know how in a longer lived society.

3)similarly building more durable equipment, which is an engineering problem, uses less resources and less risk of failure, again requiring less worker bees and allowing for automation of trivial tasks. We have lost this art in a one-time-use society

4) No one said we had to send JUST ONE ship alone on a journey. I see them traveling as a fleet of various specialized ships and even separate but interacting societies, much like the Greek city states: if one ship/society fails it is simply replaced or it’s tenants evicted. Each ship might support only of a few tens or hundreds, maybe a thousand occupants, each controlling its own technology and population. There would be trading of specialty items and mates, technology and education. Greenland failed not because it was small and the winters were harsh but because it was isolated. small villages in Norway, Siberia etc. have done very well. I suspect, for example, the the gene pool for their cattle lost its diversity and the inbred offspring could not survive the winter. On the way to the stars not all fleets may make it, but fleets that survive do so because they are not single-egg world baskets .

The last point , the real reason for most mass migrations in history are war and famine ( limited resources), and ideological/ religious persecution, this will beyond a doubt happen in human colonies founded in the outer solar system as well as on earth.

@jkittle

Your suggestion of extended lifespans, freezing eggs/embryos to reduce the problems of maintaining a society over 10’s of generations makes sense. If we can also hibernate humans (possibly engineered) too, then perhaps single generation journeys might be possible.

The more we can make our technology work like biology, the less problem we will have with entropy. Ship systems would be self repairing and work more like a biosphere. This could reduce the expertise and spares required to maintain the ship.

Paul, I’m surprised you mention C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien without also mentioning that they were in fact totally opposed to the vision of the human technological mastery of spaceflight. This is very clear in Lewis’s science fiction, particularly That Hideous Strength, which parodies and condemns the scientific/technological view of life, and offers a religious/mystical one in its place. Tolkien, too, saw the world very much in terms of rural village good versus urban industrial evil; I once read the anecdote that he once sent back his tax return with the comment: “Not a penny for Concorde!”

Note to Greg Matloff: playing around with the equation for solar sailing given in the Starflight Handbook, I found that the solar sail does not in fact provide usable propulsion in the case of stars of less than about half a solar mass, because the luminosity of smaller stars falls off much faster than the mass, so below a certain size of star the thrust from a solar sail is less than the gravitational attraction of the star on that sail. Use of an even thinner sail material, such as the graphene you’re discussing above, would of course allow solar sails to be used at smaller stars. However, I wonder whether it would be thin enough to make a solar sail usable at a red dwarf?

Astronist writes:

Exactly so — Lewis felt at odds with many of Stapledon’s ideas and they in fact led him further along the path toward his own later science fiction. Was not aware of the Tolkien comment – thanks for passing it along!

<for a space habitat to be self-sufficient, it needs a population of something approaching a hundred thousand. Certainly tens of thousands of people. Then you have to say, what are they all going to do? If you have a large population like this, what will they do between stars?

Humble suggestion. Build a ship capable of supporting a population of a hundred thousand.

And send it to the stars with crew of, say, 50 men and women.

Mission for the next 1000 years: "Go forth and multiply" ;-)

Astronist writes:

I checked with Greg on this and here is his reply:

“To my knowledge, no one has done a comprehensive study of solar sail use near red dwarf stars. I think that the correspondent’s concepts are very useful, especially since most stars in the galaxy are red dwarfs. My closest approximation to this work is consideration of sail deceleration in binary systems consisting of widely separated red dwarf and giant stars. “

Paul and Astronist, now I am confused. I know that the ratio of gravity to solar pressures is an absolute condition for zodiacal particles to accelerate away from a star, but I thought solar sails could tack. Does that only apply for small sails?

@SF reader

the idea of a moderately expanding population in a traveling world ship does solve a lot of problems, not the least of which is requiring less resources at launch. Genetically yours is a fine idea and acts to reduce inbreeding in the out years especially if some of the women in each generation are willing to act a surrogates for frozen embryos. Some couples and singles may opt to use frozen sperm or eggs. A rate of only a few individuals per generation is enough to reintroduce genetic diversity.

I noted that the Hubble telescope confirmed the presence of some small, presumably icy bodies under 1 kilometer in diameter in the Kuiper belt. If one of these could be set in motion to escape the solar system at a speed of 100 years per light year, it would provide a

means to resupply the worldships with water and other volatiles for the duration of the journey. This much mass would also provide for radiation shielding. This resource would allow for growth in transit. soo0.. how does one accelerate a small iceburg to 1% lightspeed?

plenty to reply to here:

I would assume that any permanent space habitat would use centrifugal force to create artificial gravity similar to earth (perhaps you could have smaller sections with higher/lower gravity if desired). Weightlessness does degrade the body quite a bit without extensive exercise. And the sedentary culture certainly hasn’t made us healthier or longer lived (see:obesity), rather it is medicine and a safer environment that did this.

Easter Island is a good example here. Their indigenous society was collapsing from war and ecological collapse even before the Europeans arrived.

Indeed, variety is pretty important for us humans. That’s another reason I favor space colonization – it will be the antithesis of lethargy/decadence (I can’t think of the proper word).

That can definitely be seen in Lord of the Rings, with the idealized Shire vs Mordor.

I very strongly doubt that machines could raise children, at least not into a healthy mental state. They would probably be autistic at best, or mentally… “inhuman” at worst, like feral children. Maybe if you got the machines to the point of replicants from blade runner, or ghost in the shell, it would be viable. But that kind of technology seems even further off than worldships, barring breakthroughs.

Sorry for the long post there, I wanted to reply to as much as I could. Now, for my post.

Solar system colonization will probably take place well before interstellar voyages. The economics of mining and space tourism will help push this forward. Interstellar distances really are a ridiculous engineering challenge. While there are few things more romantic than flying to the stars, practically it won’t make sense for awhile. You can get much greater returns on less investment (better ROI) by increasing our observation of the stars, such as putting a telescope at the suns gravitational lens.

Flying to the stars will only truly make sense when we have a definite destination. Either there will be an extremely valuable resource out there that isn’t in our system (unlikely), or we’ll find an exo-earth(s). Once there is a definite worthwhile destination, there will be factions of society who will want to venture there, guaranteed. Then we can move forward with planning an interstellar voyage, as many more people will be supporting it.

A worldship could definitely work, although you’d have to be careful of sociological issues that could arise. We wouldn’t want them to self-destruct, or turn into some insane theocratic cult society. Variety in the population, degrees of separation (more than one worldship?), checks and balances, etc. will be needed. I believe that some of the worldship population will disembark onto the exo-earth, but not all of them will.

Then of course, instead of sending a city-state into space, you could send small fast ships with skeleton crews and genetic banks. However, that would take on a very different character overall, and it may be more difficult to pull off. I believe that there would be no lack of applicants to the city-state worldship.

Rob Henry writes:

Rob, I’m not suite sure what the question is. Tacking shouldn’t be restricted to just small sails, but let me know further what you’re getting at here. Greg is probably the best one to answer you and I’ll be glad to check with him.

Paul, since Astronist did not mention the poor performance of sails near a red dwarfs as a problem in itself, but rather he inferred the problem as the ratio to gravitational attraction, I took it that this ratio was fundamental to his particular concern. The only problem that I could think of this nature, was that condition that applied to zodiacal particles. Due to the variable nature of light and solar wind acting on these particles, their angular momentum around the sun becomes canceled, and subsequently their fate is always to fall into the sun or escape directly. A similar effect around a red dwarf would have our probe always fall in (we would have to aim it to come very close to the surface of such stars, and their varied effects), no matter how small its hyperbolic excess, unless it could redirect the non-gravitational forces acting on it.

Alternatively Astronist might have been concerned that such a probe could not slow down on the approaching leg of the journey, but (while true) this seems no problem at all, since the lower surface temperature means that the probe could approach far more closely to the stellar surface and thus have as great a chance of cancelling all its hyperbolic excess.