This is a big week for exoplanet news with the continuing presentations at the Extreme Solar Systems II conference in Wyoming. But I’m going to have to be sporadic with posts this week because of ongoing commitments. The papers for the upcoming 100 Year Starship Symposium are due within days, which is a major driver, but I’ve also got even more important matters unrelated to my interstellar work to attend to. I’ll probably be able to get another post off this week, and then we can catch up a bit next week. For now, here’s a story I want to get in that involves things we can’t see.

Remember ‘Invisible Invaders’? This 1959 drive-in classic involved aliens you can’t see in spaceships that are likewise transparent, arriving on Earth to take over the bodies of the recently deceased. John Agar and Robert Hutton spent a lot of this movie chasing a comely physicist (Jean Byron) when they weren’t working out a way to foil the aliens’ plans to take over our planet in three days. Knowing my love of old movies, a friend recently burned a copy of this one for me, along with the equally challenging (in terms of suspending disbelief) drive-in classic ‘The Wasp Woman’ (1959).

I will spare you the plot of ‘The Wasp Woman.’ The reason I mention ‘Invisible Invaders’ is that a certain buzz is going around about an ‘invisible planet,’ which sounds so much like the title of one of those 1950s films that I wish someone had actually produced it. But let’s jolt ourselves back to reality. The planet is one in the same system as Kepler-19b, though not the same as Kepler-19b. And of course both planets are invisible to us. If you think about it, all but a handful of the exoplanets we’ve found are worlds we’ve never actually seen, but whose presence we can study through things like lightcurves (transits) and radial velocity wobbles shown by Doppler methods.

Let’s start, then, with Kepler-19b, a world some 650 light years away in the constellation Lyra. We know a bit about this one, discovered by Kepler’s unswerving gaze on its field of view as it transits in front of the primary. The planet is roughly 13,500,000 kilometers from its star, which allows us to calculate a temperature of somewhere around 480 degrees Celsius, and by studying its transits with care, we can determine that its diameter is 29,000 kilometers. This news release from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) notes that it may be a Neptune-class world, but it’s also true that we don’t know its mass and basic composition.

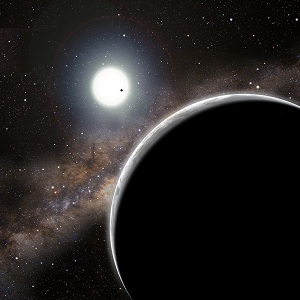

Image: The “invisible” world Kepler-19c, seen in the foreground of this artist’s conception, was discovered solely through its gravitational influence on the companion world Kepler-19b – the dot crossing the star’s face. Kepler-19b is slightly more than twice the diameter of Earth, and is probably a “mini-Neptune.” Nothing is known about Kepler-19c, other than that it exists. Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA).

The method scientists use to uncover an apparent second planet in this system is transit-timing variations, which David Kipping has used to such good effect in discussing how to detect moons of extrasolar planets. Kepler can tells us how long it takes between transits, and what’s interesting about Kepler-19b is that the transits, instead of being extremely regular, are showing up with variations of about five minutes. That’s a sign that the gravity of another planet is pulling on the planet we can see, although figuring out what the other planet is creates a problem.

Could this in fact be an exomoon we’re picking up through transit timing variations? The authors of the paper doubt it, finding that a moon of the necessary calculated mass would probably be large enough to show up in their data:

…it would probably be big enough to be seen in transit. We examined each transit by eye, to see if any deviated significantly from the single-planet model, as mutual events of the co-orbiting planets would cause shallower transits…, but we found no features of interest. Furthermore, in this scenario, the b-c mutual orbital period would need to be near-resonant with the pair’s orbital period around the star, so that the TTV signal aliases to the long Pttv = 316 day signal. We find this scenario unlikely.

We have no radial velocity clues that this world exists, and it evidently does not transit its star, which would indicate an orbit tilted in relation to Kepler-19b. So the range of possibilities is wide. “Kepler-19c has multiple personalities consistent with our data. For instance, it could be a rocky planet on a circular 5-day orbit, or a gas-giant planet on an oblong 100-day orbit,” said co-author Daniel Fabrycky of the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC). Learning more will involve not just continued Kepler observations but also future work with instruments on the ground.

The paper is “The Kepler-19 System: A Transiting 2.2 R_Earth Planet and a Second Planet Detected via Transit Timing Variations,” accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

The most important result for Centauri Dreams is perhaps the poster

by Dumusque et al on Alpha Cen:

No planet larger than 4 Earth mass with a period shorter than 300 days.

” The planet is roughly 13,500 kilometers from its star…. ” Is that correct?

That sounds awfully close.

Curt, good grief, thanks for catching that. It’s 13,500,000 kilometers. I must have been asleep at the keyboard!

Regarding the possibility of Kepler-19 “c” being a satellite of planet “b”, while they find the prograde satellite case unlikely, they are more open to the possibility of a retrograde satellite (or perhaps quasi-satellite) although they do admit this is a rather “exotic” scenario.

Looks like they found a Tatooine.

http://www.nasa.gov/centers/ames/news/releases/2011/11-68AR.html

@Schneider: “The most important result for Centauri Dreams is perhaps the poster by Dumusque et al on Alpha Cen:

No planet larger than 4 Earth mass with a period shorter than 300 days.”

Very relevant and interesting indeed, and maybe not so surprising either. And I would not expect a large planet at greater distance either, in such a close binary system.

Question: is that result for A or B or both?

Is there any link available to that information?

About alpha Cen:

– it is for alpha Cen B

– the info is private communication from Dumusque but everyone could see the poster in the Conference.

JS

Why is John knoll from the team responsible for the special effects in star wars on the panel of tomorrows NASA Kepler press conference?

I hope they actually have something significant and scientific to report, and they’re not just going to make this into a media carnival about ‘the possibilities’

@Tom

See “Tell us about your current research project. ”

http://www.seti.org/meet-our-scientists/laurance-doyle

Connecting the dots = exoplanet found in a binary star system.

Of course it will probably be a hot Super-Earth etc.

@Michael:

You’re right: Kepler 16c

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn20922-astrophile-the-most-surreal-sunset-in-the-universe.html

and apparently another dozen or so suspected circumbinary planets in the kepler database, with one or two transiting (so far). As reported by S.S. in his blog catdynamics. What surprised me (and everyone else) about Kepler 16 is that it’s such a wide binary AND eccentric. I assumed the first one found would likely be around a system with a period of a few days and thus a circular orbit. Sometimes, one just gets lucky…..