I’m just back from a long trip and am only now catching up on some of the news stories from late last week. Among these I should mention the discovery of the world with the double sunset, identified through Kepler data and reminiscent of the famous scene from Star Wars, where Luke Skywalker stands on the soil of Tatooine and looks out at twin suns setting. I remember carping about the scene when it first came out because it implied a planet that orbited two stars at once. Now we have confirmation that such a configuration is stable and that planets can exist there.

Kepler-16 isn’t a habitable world by our standard definition, but much more like Saturn, cold and gaseous. One of the stars it circles is a K dwarf of about 69 percent the mass of our Sun, while the other is a red dwarf of about 20 percent solar mass. Some 220 light years away in the direction of the constellation Cygnus, the system is fortuitously edge-on as seen from Earth, allowing Kepler scientists to identify the transits of the planet orbiting both stars. So we have two stars and one planet all eclipsing each other, with the planet’s gravity affecting the precise timing of the stellar eclipses. And each transit occurs at a different orbital phase of the inner star.

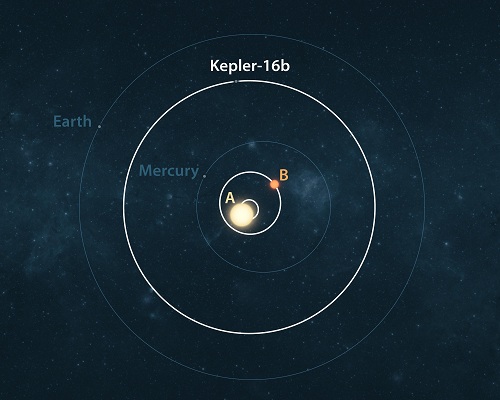

Image: This artist’s conception illustrates the Kepler-16 system (white) from an overhead view, showing its planet Kepler-16b and the eccentric orbits of the two stars it circles (labeled A and B). For reference, the orbits of our own solar system’s planets Mercury and Earth are shown in blue. Though the planet orbits its star from a distance comparable to that of Venus in our own solar system, it is actually cold. This is because its two parent stars are both smaller than the sun and don’t give off as much heat. Credit: NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech.

This is obviously demanding work, but the existence of tertiary and quaternary eclipses at irregular intervals demonstrated the changing position of the two stars as each planetary transit occurred. Researchers were then able to uncover a planetary orbital period of 229 days, while the stellar binary is in a 41-day orbit. It’s interesting to note that the smaller of the two stars is also the smallest low-mass star to have its mass and radius measured at such high precision. The issue of precise stellar measurements is one we’ll return to soon as we look at a paper pointing out how difficult the measurement of stellar radii can be when dealing with M-dwarfs, a fact that has a bearing on what we can deduce about the exoplanets found orbiting them.

Kepler principal investigator William Borucki points out in this NASA news release that most stars in the Milky Way are part of a binary system, so we now see that in addition to planets orbiting around the individual stars in such a system, we also have an option for circumbinary orbits that may offer even more exotic venues for astrobiology. The discovery is also satisfying in a cultural context — I like what John Knoll of Industrial Light & Magic had to say about scientific discoveries and imaginative portrayals like Star Wars:

“Working in film, we often are tasked with creating something never before seen. However, more often than not, scientific discoveries prove to be more spectacular than anything we dare imagine. There is no doubt these discoveries influence and inspire storytellers. Their very existence serves as cause to dream bigger and open our minds to new possibilities beyond what we think we ‘know.'”

That’s certainly the case here, and the push and pull of imaginative depiction interfacing with science is woven through the history of the last hundred years. A science fiction tale may set a young student on a scientific career, which may in turn uncover something that trumps the original story, but in its own way provides fodder for the next generation of writers and filmmakers. The individual scientist may or may not care for science fiction, but from a cultural perspective, science and fiction weave a continuing, enthralling dance, one that can energize non-scientists and build the public case for keeping the discoveries coming.

The paper is Doyle et al., “Kepler-16: A Transiting Circumbinary Planet,” Science Vol. 333 no. 6049 (16 September 2011), pp. 1602-1606 (abstract).

I wish the media et al would come up with another example of a fictional binary star system besides Tatooine. I know that is what the masses are most familiar with – and in all likelihood it was their first introduction to the concept – but I would like to see some other examples for a change of pace and give some actual science fiction stories some credit (let us be honest here, Star Wars is more space fantasy than science fiction).

I also questioned how life on any Earthlike world could even survive having two stars in the same class as our Sun assuming that world is about the same distance in its orbit as our planet is. I am sure the Star Wars fans will come up with all kinds of explanations, but those two Tatooine suns look pretty Sol-like to me. And the lower one from that famous scene in the first (fourth – oy) film is only red because it is closer to the planet’s local horizon, not because it is a red dwarf.

In any event, this real discovery is good because it increases the chances for more double and perhaps even higher stellar number systems to have have planets, with perhaps some of them being at the right size and distances to support life.

By the way, this whole thing reminds me of when Jurassic Park premiered in 1993. Just in the nick of time, paleontologists announced that they had found the fossilized remains of a velociraptor that was just about as big as the ones depicted so famously in the film. Wheh! Before that all known raptor species were about the size of a modern chicken. Then again, find me a Hollywood film that doesn’t take liberties with reality whenever they want to.

To further explain the comments in the last paragraph of my post from above, the entire Star Wars saga (complete with new unnecessary and unwelcome tamperings by Lucas) came out on Blu-Ray the same day that the real double sun system was announced – a mutual promotion.

Flawed as it is, I would like to see NASA and other science institutions doing more public outreach like this. It is obvious the media will eat it up and do their part.

“Working in film, we often are tasked with creating something never before seen. However, more often than not, scientific discoveries prove to be more spectacular than anything we dare imagine.”

In this particular case, Chesley Bonestell was painting imaginary planets orbiting binary stars at least as far back as 1951, and created beautiful set to illustrate Willy Ley’s “Beyond the Solar System” (1964).

While Kepler has identified many interesting planets and solar systems, planets orbiting close binary stars have been imagined for well over half a century, at least.

I wonder what other planets may exist there and how far out they orbit from their binary suns. Not sure if Kepler can provide an answer to that question.

Perhaps fainter transit signals might be seen if other planets do transist from our ( Kepler’s) line of sight. Or more timing variations could be identified.

Time will tell, we’ll just have to wait and see.

This is another possibility for planets discovered. The Rare Earth hypothesis just lost another factor (after already having lost many!).

Even staunch Rare Earthers like Brown contend the Universe is full of planets with life, at least simple creatures. It is the amount of intelligent life, especially ones with technology, that they question.

Perhaps just as most of the planetary systems we have found so far do not resemble ours, the Universe consists of forms of life that do not resemble the ones found on Earth, either. And I do not just mean they an extra pair of arms or pointed ears. Thus our difficulty in finding them, or they us, so far.

Now waiting for Earth-like or Super-Earth double planets in habital zones. That would be pretty exciting, and to my knowledge, not something seen in many movies. Except for maybe Romulus and Remus (Star Trek)?

Just off the top of my head, I’d say the Tatooine arrangement could be made to work if both stars were approximately G8. Each star would have half sol output, and their apparent diameters, though slightly smaller, would not be noticeably different to the casual eye.

The other thing that has to be accounted for is that both suns appear to be separated by only a couple of solar radii. If they orbited this close, they would both be distorted into a distinctly egg shape. Their lack of ellipticity could be accounted for by the fact they have a wider orbit and the shot was taken when they were near minimum visual separation. Incidentally, any shot taken of the stars near minimum visual separation would also minimize their non-spherical nature.

Talking of distorted stars, wonder if there are any planets orbiting W UMa-type binaries. That would be a truly surreal sunset!

If it has a large moon orbiting close in heated by tidal forces it might be warm enough for life, think Io but with an atmosphere.

ljk

i think it is time to accept that we are the only intelligent life forms in this galaxie, but Why would we want to have other intelligent biengs in this galaxie. Without them we can take every planet for ourselfs. We will have no competition.

So it is much better that we are the only intelligent biengs in this galaxie. Why do we want to find other intelligent biengs anyway ?

@ Dave Moore The stars in the figure shown are not to scale: the separation of the stars is about 0.224 AU (semi-major axis) while the planet’s orbit has a semi-major axis of 0.705 AU. It’s that small ratio that led some theorists to believe that planets couldn’t form in such a binary system; coupled with the eccentricity of the binary orbit.

@ljk I doubt the IL&M folks really thought a few degrees separation would have made such a drastic change in the colors of the stars in the famous scene: they simply screwed up and didn’t make the red star much smaller than the other (which no one, graciously, pointed out during the press conference).

@ Paul I’d be very wary of over-interpreting the paper in astro-ph (don’t have the reference handy) that says the Kepler Input Catalog has grossly mis-typed many of the K & M stars (and thus that they’re 2x smaller than expected). There’s no sign of that error in the paper on Kepler 16b and it’s extremely unlikely that the KIC authors would make such a large, systematic error. You might want to solicit comments from one or more of the KIC authors (Dave Latham would be a good choice, for example).

+2 for Dave Moore

I would go beyond that, circling a binary pair of G8 stars could be better than Sol. About the same visible light and heat with less UV sounds pretty good to me. But maybe that’s just because I had 4 skin cancers frozen off Friday, and an acquaintance was diagnosed with metastatic melanoma this week.

I wonder what the theoretical limits are for imaging a earth like world from the comfort of our own solar system as discussed in Mr. Gilster’s book. For example, could one really image weather, oceans, land and possibly even note if there are artificial lights on the night side?

Bob, the imaging ideas you’re referring to were those of Webster Cash, who had developed three different concepts for exoplanet imaging, including one that he believed could get close-up views, which he defined as being close enough to see continents, etc. Cash is still active, though his ideas have moved around a bit, and I don’t know where he currently stands on the absolute theoretical maximum for such systems. But what an idea, to see an exoplanet that close! We’re talking decades away, of course, and by then there will doubtless be new concepts that may even be better, though demanding futuristic engineering, etc.

Paul, Thanks. I agree that is an exciting idea. I have confidence clever people can make it work in the several decades time frame. I am currently enjoying your book.

You have a point, but with limited validity. They would have to be extremely different to make them more difficult to find than Vulcans. And just like all the planets we have found so far have the same shape as Earth, there are likely to be certain characteristics we would expect to find in most or all ETI. One example: They would be intelligent, as a matter of definition.

Everything else being equal (age, rotation period etc.) a G8 star probably emits MORE UV than the sun, since the convective zone is deeper which means it’s more chromospherically active (hence more flares and coronal mass ejections).

So you’d want a pretty thick ozone layer and/or SPF 100+…..

Going back to something ljk said, someone once pointed out that the number of possible DNA sequences is many orders of magnitude greater than the probable number of planets in the universe. So even if we limit our thinking to DNA-based life each planet (and all the planets together) may sample only a tiny fraction of possible sequences. There may be no typical life. Each planet’s life evolved from whatever was “good enough” to get started, and may vary drastically from all the others. This is even more likely if many different basic biochemistries are possible.

I can’t help but note 2 very important factors here.

Firstly the gravitational effect of a widely separated pair of stars would make planets encircling both gradually spiral a little outwards, thus giving potential to offset the brightening of a star with age and widening the potential continuously habitable zone. This induces me to speculate that some of these sorts of planets might be much better candidates for higher life to evolve on that the Earth was.

Secondly we could only detect this set-up, without decades of data and very low signal to noise ratios if all three were freaky aligned in exactly the same plane – as well as this being our viewing plane To have found one already, makes me wonder if planets within such a set-up are incredibly common.

In fact, transiting circumbinary planets is a rather long story starting in 1990 with the paper “The photometric search for earth-sized extrasolar planets by occultation in binary systems” (Schneider & Chevreton 1990, Astron. & Astrophys., 232, 251), followed by “On the occultations of a binary star by a circum-orbiting dark companion” (Schneider 1994, Planet. & Spa. Sci., 42, 539).

Laurance Doyle, first author for Kepler-16b, was introduced to this subject in

the early ’90s, with the paper on the eclipsing binary CM Dra “Ground-based detection of terrestrial extrasolar planets by photometry : the case for CM Draconis” (Schneider & Doyle 1995, Earth, Moon and Planets, 71, 153).

Follow developments on Kepler-16b in http://exoplanet.eu/planet.php?p1=Kepler-16+%28AB%29&p2=b

@ljc: The Rare Earthers actually denied the possibility of planetary formation and stable orbits in binary and multiple systems, so it matters. Also, I wrote that the Rare Earthers lost ANOTHER factor, NOT that this was the ONLY reason why they were wrong. Other important factors they ignore is anaerobic and heat-stable complex life and environmental stress speeding up evolution. Rare Earthers usually use the dishonest strategy of whenever someone points out an error, they just say that the particular error in question is of minor importance, and exploit the fact that there is not enough time during a typical debate to show that the vast majority of Rare Earth factors is spurious. Rational Wiki calls it “Gish galloping”.

@Henk: We do not need the WHOLE galaxy for our own to get rid of competition, with hundreds of billions of solar systems. Many intelligent species probably live in human-hostile planetary environments, while many of those in human-hospitable planetary environments are likely few individuals and can coexist peacefully with moderate numbers of immigrated humans. Then there is certainly people who would voluntarily prefer to live in artificial habitats.

@NS: Part right. Sure, different biochemistries are probable in very different environments. But you ignore that life as we know it actually evolved from a complex mosaic of different forms of primitive proto-life pre-“as we know it”. There are both nucleic acids and proteins capable of self-replication, so they most likely started indepentently and united through symbiogenesis. Then cell membranes most likely have a third, lipidic origin. Both the outer space origin theory and the hydrothermal vent theory have found molecular indications for themselves. In such a complex mosaic, life as we know it emerged gradually as a winning “best of many worlds” combination. But, as mentioned above, best in one environment can be very bad in another environment. I would NOT expect Earthlike biochemistry on Titan, but I think there most likely is some form of life there.

henk said on September 19, 2011 at 17:12:

“i think it is time to accept that we are the only intelligent life forms in this galaxie, but Why would we want to have other intelligent biengs in this galaxie. Without them we can take every planet for ourselfs. We will have no competition. So it is much better that we are the only intelligent biengs in this galaxie. Why do we want to find other intelligent biengs anyway ?”

You have some special knowledge about this lack of aliens in the Milky Way? You also seem rather bent on galactic conquest. What happens if there are ETI and they too have a similar intent for other worlds? As for why do we want to find other intelligent beings: Read through just a bit of this news blog to get your answers.

Eniac replied to my post on alien life forms on September 19, 2011 at 23:09:

“You have a point, but with limited validity. They would have to be extremely different to make them more difficult to find than Vulcans. And just like all the planets we have found so far have the same shape as Earth, there are likely to be certain characteristics we would expect to find in most or all ETI. One example: They would be intelligent, as a matter of definition.”

I should have clarified that I don’t think among all the possible forms life and intelligence may take in the Universe that most or all of them would be so radically different that neither side would ever recognize the other as organic and aware. If they are, then SETI as we currently run it will be fruitless.

However, I don’t think aliens would need to be too different for us to have a hard time recognizing them. As noted in a recent article on this blog, if an exoplanet’s highest order of life is something similar to the cetaceans, then we will not be hearing from or detecting them until we can get a star probe to their world.

That is the big question of SETI: How many intelligences out there not only have the ability to signal others in the galaxy, but also have the desire and the will to do so? Again, I wonder if humanity is unique in this trait? Or maybe we are the primitive slackers when it comes to SETI as practiced throughout the Milky Way.

While we may well be the only intelligent (by which definition of the term?) life forms in this galaxy (at the present time), to say that NOW, with our current state of knowledge, is the time to accept this as fact, is a wee bit premature.

Though it should be noted that given the size of the galaxy, we wouldn’t actually have to be the only intelligent life form in it to be functionally alone.

@Martin:

There is no evidence for this, and really no way it could be true. There are no proteins capable of self-replication. All proteins are made under the control of nucleic acids, and it is quite clear that they must always have been. Protein sequence cannot plausibly be copied biochemically, and there cannot be life without the copying of genetic information. Similarly, DNA is not suitable to perform catalysis, without which there also cannot be life. Lipids can neither perform catalysis nor copy information. RNA is the only known molecule that can do both, and we know it can because it still does so in today’s organisms.

Furthermore, RNA tends to function at the most critical interface between nucleic acids and proteins as components of the ribosome (the protein factory) and as transfer RNAs (the keys to the genetic code), both of which include the most conserved genetic sequence that exists. Some of this sequence is recognizably conserved across ALL species, and thus thought to date all the way back to LUCA and beyond.

For all these reasons, the leading (by far) hypothesis of early life is the well-known RNA hypothesis.

Since the other components are not viable by themselves, symbiosis is not a possible way for them to have come together, rather we have to conclude that they were picked up or synthesized as non-living tools by RNA based protoorganisms to gradually improve their biochemical prowess.

@coolstar: I think a G8 star does not have such a deep(er) convenction zone as to pose a UV problem. What you describe (flares, CME) is something I rather expect for M class stars, where this is actually common.

Later G stars (G3 – G8) may indeed be more optimal for a life-bearing planet (relatively more photosynthetic light, longer stable lifespan on main sequence) as Joy was suggesting.

@Eniac: “There are no proteins capable of self-replication”.

How about prions? These are proteins and self-replicating.

Although I do agree with what you say on RNA-life as probably the earliest life (the RNA hypothesis), with regard to symbiosis, however: mitochondria, which have their own DNA and membrane, maye have been independent viable lifeforms. Furthermore, it is highly unlikely that complex structures like mitochondria and other complex cellular organelles were picked up as non-living tools.

More UV is not necessarily much of a barrier to life evolving however. On the assumption that life arises underwater, there will always be some depth at which sufficient UV is filtered out to be safe, and enough light penetrates to be useful for photosynthetic processes (not that life necessarily needs photosynthesis, either).

Indeed, the leading hypotheses now suggest that the adaptions of microorganisms to resist UV damage are the pre-adaptions that later allowed for the evolution of oxygen resistance, oxygen respiration, and oxygenic photosynthesis. Which may even suggest that a planet with more UV exposure than earth would be even MORE likely than earth to evolve oxygen respiration and oxygenic photosynthesis, a thick oxygen rich atmosphere with a thick ozone layer, and complex lifeforms.

Mitochondria are descended from independent viable lifeforms (bacteria).

But the mitochondrial endosymbiosis event occurred long after the origin of life and has nothing to do with abiogenesis. It explains the origin of eukaryotes, not of life itself.

Symbiosis probably was involved in abiogenesis, but most likely it was symbiosis between disparate nucleic-acid based replicators (either RNA or some pre-RNA nucleic acid, most likely not DNA). In the sense that the very first self-replicating RNAs would basically be single, naked genes, multi-gene genomes probably arose by symbioses that combined these single-gene replicators together. It is certainly possible as well that not all these RNA (or other nucleic acid based) replicators arose from a single original replicator (LUCA was a cell that already had DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids. Universal common descent only goes back to LUCA. Common descent does not necessarily have to be universal for the period before LUCA). Several independent lines of self-replicating nucleic acids could have arisen.

Prions replicate by inducing/catalyzing a conformational change in another protein to match it’s own. That other protein also has to be very closely related, if not identical, in sequence to the prion itself (a prion is typically a mutated version of its target).

And all these proteins, as well as the prion itself, originally arise by being translated from a nucleic acid sequence. No nucleic acids, no prions.

Amphiox, don’t you think your use of the fact that “Prions replicate by inducing/catalyzing a conformational change in another protein to match it’s own” as a dismissal, is a little too unimaginative. For a long time there have been hints (though never conformation) that these also carry genetic information, and their unit of infectivity has never shown to be less that about 1000 proteins. Perhaps the truth lies at your end of the assessment, but its also well possible that it lies half way between those of you and Ronald.

@Ronald ALL convective stars have significant chromospheres and corona, and the danger from flares goes up as one goes down the spectral sequence. So, of course M dwarfs would be worse (not a point I commented on).

Two G8 stars would MORE than double the UV emission over the liftetime of the system. It would likely be MUCH worse than this if the stars are close (closer than Kepler 16 as that’s not really a close binary as such things go) since the rotation period of each star would be locked to the orbital period for periods less than 10 days or so. Thus the stars would never spin down, and would remain quite active throughout their main sequence liftimes. So, I was being conservative at SPF 100+! No one knows how much a danger this level of UV emission poses to the development and evolution of life.

I actually study these systems as part of my job.

It’s long been suggest that the habitable zones of K dwarfs might be good abodes for life. HOW good fluctuates depends on whom you’re talking to: tidal locking and flaring MIGHT not be intractable problems. Since this regime (of orbital periods) has been well mined by Kepler already, with only a handful of roughly earth sized planets detected in the habitable zones (roughly 5, give or take a few), it seems as those we can already say that some predictions have been widely optimistic.

Don’t some here find it disappointing that in a modern world captivated by Harry Potter, we can’t still give a little credence to the forces of vitalism. The metabolism first theory of the origin of life cannot be fully ruled out until it is demonstrated that there are no circumstances in which a “genome” that simply consists of selfreplicating elements, none of with hold more than a bit of information (unlike the hypercycle theory), are incapable of sustained Darwinian evolution under any circumstances. This proof has not quite been achieved, and even if it had there is still the prion copout that I wrote of above. Thus, surely, the more imaginative must still be free to fantasise that proteins can evolve their own sort of life.

@Rob, of course you are free to fantasize as long as you do not expect your fantasies to have anything to do with the truth. Amphiox has put it very well, I agree with every bit he says and have nothing to add.

@coolstar: I love to stand corrected by and learn from the real experts, so correct me here if I am wrong but, with regard to UV, flares and spectral type:

Isn’t it so that as one moves down the spectral sequence, but still within the solar type range, let’s say from latest F (9) through all G to early K (K0,1, maybe 2), the ‘normal’ UV output goes down, while at the same time, the flare/CME risk increases only very marginally at first only to become a real risk (much) further in the sequence?

In other words, if this is right, there would be an (near-)optimal spectral type (also correllated with B-V color index and luminosity) where UV is low, stable main-sequence lifespan is long and flare/CME risk is still low. I would tentatively put that optimumj somewhere around G5/G6.

Ampiox: agreed that UV has its positive effects, both on formation of an ozone layer and possibly on development of life. However, there is a maximum to all good things: it seems that the young sun, and young solar analogs, emitted tens to a few hundred times as much UV as now. And that this high initial UV may actually have been prohibitive to life’s arising in shallow water, until the level subdued to below a ‘tolerable’ threshold.

Prions have lost their ability to self-replicate completely on their own because of their adaptation to other lifeforms. There is actually molecular evidence that proteins began independently of nucleic acids. Neither formed in the image of the other, they formed independently and united later through symbiogenesis. How the h#ll should there be enough protein components around for nucleic acids to “domesticate” if proteins could not self-replicate on their own? Eniac seem to be using strawman arguments all the time.

Ronald, you UV questions have set me thinking. I’ve recently had an epiphany as to how unproductive it is to look for Earth-like planets. No matter what the difficulties involved in calculation, we should be looking for what we want.

Rather than comparing the profile of discovered planets against Earth’s we should compare it against how optimised we think conditions on that planet are to the development of higher life, and to this purpose UV levels of their suns looks like a good place to start.

Even without finding the exact details two (widely spaced) stars allow more parameters to adjust, and it would seem suspicious if most of these combinations were deemed worse for life that our sun without detailed calculation. That calculation should be based on an objective criterion that can be claimed to not just be grounded in the idea that such levels should be Earth-like. This is more tricky than it sounds because we do not know the extent to which the only biosphere that we know of has adapted the local (hostile?) conditions.

I would like to add that lower mass stars have a longer life and evolve more slowly, and surely that must help a bit too.

No, they never had it. Prions are single proteins. How would this have worked, in your opinion? How would a single protein go about making a copy of itself? Amino acids do not have complementary pairing, for one.

Such as?

The same (mostly unknown) way that there were enough nucleotides to form the first organisms to begin with.

Sorry about that. I wasn’t aware. Could you point out just one, please?

Eniac, I must be in a pedantic mood because I agree that there is no evidence that prions could ever replicate themselves, and furthermore I recall that there was epidemiological evidence that some prion disease outbreaks can start spontaneously (that is without an infective agent being introduced), yet still find cause to disagree.

Your statement that the infective agent is SINGLE proteins is against the weight of evidence. All prion diseases progresses by forming an insoluble plaque, a process that necessitates that the proteins forming them are closely associated with each other. It MAY be true that the misfolding of a single protein can start this whole process, but then we must explain why the minimum unit that can provide infectivity always seems so large.

Note that this opens up the (remote) possibility that some strains retain a fairly high quantity of information within their patterns of conformational changes that can be replicated with sufficient fidelity to allow Darwinian evolution. Also of interest is that most of these diseases primarily effect the brain – just where one might expect a protein with a modern but hitherto unrecognized information storage role to reside.

We can run with this possibility and add to it another huge assumption: that proteins whose primary structures are built with very low primary structure fidelity might also be able to hold some information within them by similar means of conserved conformational changes. Thus if we let our imaginations run riot we can at least see how this would make protein only life seem a little less impossible.

Martin J Sallberg, it is very hard to see a protein only origin of any type of life. The problem is not just how natural peptides could reproduce themselves, it is how ill displaced their structures are for any sort of replication with sufficient fidelity to enable natural selection to continually increase efficiency. Once it was hoped that the preferences of association among amino acids would provide enough error correction to this process to fix the problem, however it has now been demonstrated that any such process would have a net retarding effect on potential for evolution. Sorry Martin, but I have lost my reference to the seminal paper on this topic , but I bet Eniac has it (I think it was published in Science if that helps).

Anyhow, that is my reason for my desperation to invoke high fidelity information storage in the secondary structure of microheterogeneous protein.

Rob: I love you you can be pedantic and let your imagination run riot at the same time!

As for the subject, I did not mean a single molecule, just a single protein. I understand those plaques are made from a single species of protein. If not, this would still be adequately explained by other proteins being “innocently” dragged into the aggregation. Even if you are in an extremely hyperspeculative mood, holding information is not the same as copying it. Without base-pairing, the most formidable of imaginations will be hard pressed to come up with a plausible mechanism for copying whatever information is carried by proteins.