We’ve been talking lately about space missions designed to maximize science vs. those that are at least partly geared toward public relations. But most missions will have both components, the need for public support being woven into the fabric of our ambitions. As we try, then, to ramp up the scientific return, what can we also do to keep the public engaged and instill interest in space exploration? One answer came from Wernher von Braun’s massive project for space exploration, described in a series of articles on space presented by Collier’s magazine from March of 1952 to April, 1954.

Let’s put aside all the technical problems of the von Braun concept and concentrate on it as an incentive for space missions. Al Jackson, with whom I enjoyed dinner and several good conversations in Orlando at the 100 Year Starship Symposium, recently sent me The Ugly Spaceship and the Astounding Dream, an article he wrote for the AIAA’s Horizons magazine. Al is completely upfront about the fact that it was the Collier’s series that brought him into space research in the first place. Now a visiting scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute, Al has seen aerospace from the government side (as astronaut trainer on the Lunar Module Simulator) to industry, knew Robert Bussard as well as Robert Forward, and wrote a number of papers on interstellar matters for JBIS, including work in the late 1970s on a laser-powered interstellar ramjet that I want to discuss soon in these pages.

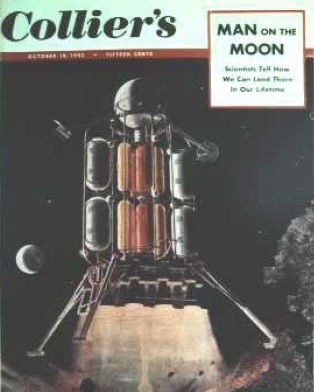

Image: Chesley Bonestell’s take on the von Braun lunar lander, an ugly spaceship with a mind-blowing cargo of ideas.

The Collier’s series, tapping the artistic genius of Chesley Bonestell, produced what Al calls ‘the most influential feat of popular science writing ever,’ with its depiction of a complete manned space program ranging from Earth-circling space stations to lunar landings and that massive expedition to Mars. And ‘massive’ is the right word, for von Braun imagined a flotilla of ten spaceships with a crew of 70 making the Mars journey, fifty of them landing on the surface. 950 ferry flights were needed to assemble the spaceships, but von Braun’s vision included the space infrastructure to make that happen, all based on ideas he had been working on in 1947 and 1948, published first in a German journal and then brought out in a hardcover edition: Marsprojekt; Studie einer interplanetrischen Expedition. Sonderheft der Zeitschrift Weltraumfahrt (1952).

But it was the October 18, 1952 issue of Collier’s that Al, then almost twelve years old, found the most fascinating, the one with the ugliest, most un-aerodynamic spaceship he had ever seen shown on final descent to the Moon. It was in the pages of this issue that he learned that aerodynamic shapes count for little in space, and as he tells us in his article, the entire series would wind up changing his life:

I came to love that ugly space ship! It cemented itself to my soul. It led me to a life in science, a B.A. degree in Mathematics, an M.A. degree in Physics and a Ph.D. in physics. Most startling, to me, that series led me to 35 years of work in spaceflight, first Apollo, the Shuttle program, and now the ISS. All due to the romance of space expressed by Chesley Bonestell, Wernher von Braun and Willy Ley.

Collier’s produced spectacle and soaring ideas, doubtless contributing to the careers of numerous scientists and engineers, even if we now find the technical specifications of the von Braun program daunting. But I sometimes wonder what we might do today to recapture some of the spectacle produced by the Apollo landings, which similarly energized broad portions of the population. Space-minded people like myself are fascinated with the Dawn mission to Vesta and Ceres, and equally drawn to the allure of the Pluto/Charon encounter coming up in 2015. But what would have the most impact on those less obsessed with deep space?

I think I may have found the right concept. It’s the notion of exploring another planet by balloon, exemplified by MGA, the Mars Geoscience Aerobot, studied by a JPL team in the 1990s under the acronym MABVAP – Mars Aerobot Validation Program. It’s an idea with an international pedigree: A balloon system for Mars designed for a Soviet space probe was also under development through the work of Jacques Blamont (CNES), although the project was eventually dropped for financial reasons.

In essence, though, the ideas are similar. The idea is to deliver a superpressure balloon system to Mars, an aerobot that would remain aloft for as much as three months, circumnavigating Mars more than 25 times. Along with an infrared spectroscopy system, a magnetometer, instruments for studying Martian weather and a radar sounder, the balloon would be equipped with an ultrahigh resolution stereo imager. Robert Zubrin and a team at Martin Marietta have more recently been working on the Mars Aerial Platform (MAP), a plan to use eight balloons to map the global circulation of Mars’ atmosphere, examine its surface and subsurface with remote sensing techniques, and return thousands of high resolution images of the Martian surface.

The views returned by an aerial circumnavigation of Mars would be little short of spectacular, as Zubrin notes in the new edition of his The Case for Mars (2011):

Today, nearly five hundred years since Copernicus and Kepler, Brahe and Galileo, most people still think of Earth as the only world in the universe. The other planets remain mere points of light, their wanderings through the night sky of interest to a select few. They are abstractions, notions taught in schools. The MAP cameras offer the possibility of taking humanity’s eyes to another planet in a way that has never been done before. Through the gondola’s cameras we will see Mars in its spectacular vastness: its enormous canyons, its towering mountains, its dry lake and river beds, its rocky plains and frozen fields. We will see that Mars is truly another world, no longer a notion but a possible destination. And, just as the New World entranced and enticed mariners here on Earth, so can Mars entice a new generation of voyagers, a generation ready to fashion the ships and sails proper for heavenly air.

Remember, I’m thinking in terms of how to kindle public interest in space and keep those fires burning, and to me the ability to see the topography of Mars through close-up imaging of its entire surface could create an experience as breathtaking for some budding scientists as the Collier’s series was for Al Jackson. We go from looking at rover tracks and landscapes limited by a rover’s range to the ability to move freely over Mars, from Olympus Mons to the Valles Marineris.

Similar missions have been proposed for Titan, with a certain scientific return as well as the potential for serious public engagement as the aerobot probes the surface of the mysterious moon. An autonomous flying robot was actually delivered to Venus on each of the two Soviet Vega probes, entering the atmosphere in June of 1985. Both balloons operated for almost two Earth days until their batteries batteries failed [see comments below]. Deployed onto the darkside of the planet at an altitude of about 50 kilometers, the balloons operated for their brief lives in an altitude where pressure and temperature were not dissimilar to those of Earth.

While the scientific return from the Vega balloons was minimal, the concept was validated. Using aerostats equipped with high-definition imaging capabilities on Mars, we may be able to re-create some of the sizzle of exploration that the Voyagers had, giving a boost to science-minded young people and providing vistas for public viewing through remote sensing that could one day be looked back on as the key players in creating new careers in science. We may or may not one day get to the stars, but if we do, it will be because the right people came across the right incentives, leading them into careers that could change the way we do space exploration.

I concur, I think it would be a wonderful project. The stereo image would stimulate sales of stereo viewers for computers and possible televisions. But even a non-stereoscopic view would make for a great screensaver or “image of the day”.

One has to consider whether mission costs could be [at least partially] offset with media deals and merchandising.

Let me first start by thanking you, Paul, for this great blog. You’re keeping the fire burning for all us space enthusiasts.

Now, on topic, how do you think Martian weather patterns would affect a balloon system in the atmosphere? Or would the balloon be high enough in the atmosphere that the windstorms would not affect it too much?

Tony, Zubrin’s work on this indicates that a balloon at an altitude of 7 to 8.5 kilometers will maintain roughly the same altitude day and night, assuming the kind of ‘superpressure’ balloon described in his book. Then there’s this, again from the book:

You wind up with an instrument package that circumnavigates the planet every ten to twenty days. Interesting concept!

And thank you for the kind words.

Sorry to be picky on such a great article(s), Paul, but both Vega balloons lasted over 46 hours in the Venusian atmosphere before bursting:

http://www.mentallandscape.com/V_Vega.htm

Odd. This is what Wikipedia says:

Yes, I think that this would be an inspiring mission. I agree that the images would be spectacular. As with the Hubble, it would probably be beat to trickle out the best pictures in order to maintain interest over a long period of time.

However, the mission’s character would not be as personable as the rovers have been. If one is looking to inspire a generation, then Robbie the Robonaut on either the Moon or Mars would probably inspire more people. And nothing could compete with real people, especially a non-astronaut such as a private tourist, teacher, or a literal mechanic with a Louisianna accent named Billy…you get the idea. Such makes for good story telling.

I still have my copies of “Across the Space Frontier”, “The Conquest of Space” and “The Exploration of Mars”. All three were given to me as Christmas presents back when I was a teenager in the ’50s. Still take them out and imagine what it could have been like. They continue to be a great read from a historical point of view and Bonestell”s artwork is still as captivating as ever. As they say, thanks for the memories…..of what might have been.

Tom

Paul, I would trust Donald Mitchell’s Web site on Soviet space probe history over Wikipedia any day. In fact, I think I would trust information from some random stranger on the street over Wikipedia on most given days. :^)

Plus, every other source I have read on the Vega mission since it happened said both balloon probes functioned for almost two whole Earth days. The two Vega *landers* did not last very long, but that is par for the course for any craft on that planet’s surface.

I see JPL docs support your case:

http://vfm.jpl.nasa.gov/othervenusmissions/veneravegarussia/

I’ll change the main entry, and thanks for the tip.

While the U.S. Stalls, Europe Moves On to Mars

Oct. 14, 2011 | 13:21 PDT | 20:21 UTC

By Charlene Anderson

The European Space Agency (ESA) seems to have gotten tired of waiting for NASA to commit to its share of the joint 2016/2018 Mars missions that were planned to lay the groundwork for an eventual delivery of samples of Mars to Earth.

Space News is reporting that, to save the two-mission plan, ESA Director-General Jean-Jacques Dordain has formally invited Russia in as a full partner. He’s asking the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, to provide its Proton rocket to launch the European Mars telecommunications orbiter and a small lander in 2016.

NASA has told ESA that its budget will not allow it to commit to launching the 2016 mission, and the hoped-for 2018 launch of the ExoMars rover on an Atlas 5 is not confirmed. If Russia accepts ESA’s partnership offer, the rover will launch on a Proton.

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blog/article/00003222/

A footnote to that 2002 article.

During the 1990’s I worked in orbital debris for 10 years.

We had the good luck of having three ESA supplied astronautics engineers to team with at JSC. They were all German.

One of them made an astounding discovery. Living in the JSC area was old Peenemünder , Joachim Mühlner. (If you have a copy of The Mars Project , can find his name in the introduction by von Braun.)

A man who worked on the V2, ICBMs, Apollo and the Shuttle, what a span!

I met him in 1998 , when I found out who he was, I interviewed him in 2000.

I could not believe my luck. Joachim was in his late 80’s , retired for some time, and quite frail and hard of hearing. A very nice man.

He died in 2004.

I only had about two hours with him, although he spoke perfect English, he would lapse into German now and then, and my German friends would coax him back to English.

His memory of working on Das Marsprojekt was a bit clouded by age, but it’s the only first hand account I have.

He recalled that von Braun , in 1948, getting bored sitting at White Sands, in his inimitable manner to think of something to galvanize the public about spaceflight.

The idea was to give all the engineering physics a rock solid underpinning.

Then write a science fiction novel.

Joachim said von Braun said ‘shoot for stars’, knock their socks off.

All the technical details, as I said, were worked out down to the bolt head!

As I said in the article von Braun’s starting point was Columbus, that expedition was about 70 men.

The great visionary Krafft Ehricke apparently had long arguments with von Braun about the scale of the project. However he was good humored enough to play along. A lot of ideas in the final blueprint are Ehricke’s . Check out the astrodynamics figures, those are pure Ehricke, see: Krafft A. Ehricke: Space Flight, Volume 2: Dynamics, Van Nostrand Reinhold (1962).

According to my notes Mühlner told me none of the team believed there would be a social – economic setting in the near future that would make the concept real, but what the hell, damn the torpedoes full steam ahead.

Even in 1953 the whole concept belonged to a parallel universe, and so it remains.

Lord knows how many teenagers, me included, went on to study math and physics because of this totally crazy concept!

There is still an outstanding problem landing heavy loads on the surface of Mars ( above a couple of tons) this is because of the thinness of the atmosphere and the high velocity of the incoming probe. For lighter loads parachutes and a bouncing ball landing works, and hopefully the curiosity probe will also land OK. I am working on a couple of ideas to solve the more general problem. fight now there is literally no proactiacla way to land a 4 man ship carrying supplies.

for and unmanned mission, The balloon idea is nice for an extended visit, but really I have to say the resolution of the orbiters imagers and sensors is very remarkable. It is not widely recognized but there are many parts of the martian landscape where we have better resolutions photos than what are available on earth.

Exciting as I and other space buffs would find the Mars balloon mission, would it be enough to capture the general public and thereby receive their support? Would it really be the Apollo of the next generation?

I think we will have to go all out, and the recent starship symposium is a taste of what is needed. I say we go for an interstellar worldship mission to Alpha Centauri. Here is one way to do it sooner rather than later, without hoping and waiting for some exotic technology to come along:

Purchase a bunch of nuclear bombs from the Russians, who will no doubt appreciate the cash for them. Then get the Chinese involved in offering their space expertise and their barren, open western desert region. Put together an Orion nuclear propulsion spaceship and launch from western China. Normally it would be preferable to build and launch Orion in deep space, but I am assuming we will not have that option here, as most other nations would bog down the enterprise due to the nuclear bomb aspect of the mission.

Once in space, find a suitable planetoid and use Orion to push it out of the Sol system. The planetoid will serve as the shell and resources for an interstellar ark. This assumes the Orion ship itself just will not be big enough to keep a human crew happy for the estimated 125 year trip to AC.

Will it matter if there are no planets at Alpha Centauri? There may be small ones in that system, or at least certainly planetoids which could be used for materials and settlement.

The point is, this mission would be BIG and last long enough into the future to give whole generations a point of interest and hope. Why not settle the Sol system you say? Oh, I am not against that eventually, but if you want the big ticket item to draw the crowds, you need something bold like Apollo, which went it was first announced, two humans had gone into space for 1.15 hours total and only a few robot probes had made it to the Moon.

And like Apollo, this needs to be done with technology and materials that we have NOW. If we keep waiting for some kind of special starship drive to come along, the present interest will be lost and so will the space effort.

The public wants Star Trek or its equivalent, make no mistake about that.

Oh yes: Watch the 1950 SF film classic Destination Moon for inspiration and even some ideas.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Destination_Moon_(film)

On the issue of the USSR success, it’s good to remember just how successful–and audacious!– our former foes were in their space program, continuing to this day with very reliable rocket systems and extraordinary engineers.

@ljk

A multi-generational project will not stir the imagination, just bore it. Exciting lauch (with lots of protests) and then 125 years of …. nothing. *Yawn*

Who remembers the excitement of the Voyager probes as they traveled to the outer system? Oh that’s right, there wasn’t any. The interest happened at the encounters. And don’t forget the public was bored of moon flight by Apollo 13, just 3 flights in from the 7. A number of flights were canceled.

@jkittlejr

While the resolution of the ground images is high, images looking down are not nearly so interesting to the general public as those with horizons. The rover images give you that, and close ups that make you feel you could put yound hand in the dirt and scoop up some sand and rocks..

Low altitude images showing ever changing vistas is far more inspiring, giving the viewer a “you are here” feeling.

I remember in 1950 when I was 9 years old wanting to see that film so bad.

I grew up in Dallas Texas , out at White Rock Lake, my parents rarely went downtown until my brother and sister and I were teenagers. So I had to wait about 2 years before that film played at a kiddie matinee near me.

Have seen it many times over the years , have a DVD of it now.

Saw it about the same year the Colliers series started, by the time I was 12 I knew exactly what I wanted to do with my life. I am amazed that I really got to work in manned space flight for more than 40 years.

IMDB credits Heinlein’s Rocket Ship Galileo as the source of the screenplay, and indeed it was . However Heinlein and screenwriter and Alford van Ronkel wrote the first draft and sort of threw it over the transom , some how it landed it the hands of probably the only producer in Hollywood seriously interested in space flight, George Pal. James O’Hanlon and van Ronkel wrote the final screenplay while Heinlein became technical adviser. (Heinlein was flabbergasted when the studio wanted to put in a scene in a night club with dancing girls! He had Pal dissuade the producer from doing this.)

The film is what I call Popular Mechanics science fiction, but it is fun and thanks to Heinlein scientifically accurate. Chesley Bonestell, who had worked in Hollywood as a matte painter did the paintings for the film, the film won an Oscar for special effects, no surprise!

(It has some awkward comedy relief which was sort of standard Hollywood in those days.)

Heinlein wrote a short story called Destination Moon which is essentially the movie and is rarely mention in connection with the film.

(There had been the 1929 Frau im Mond by the great German director Fritz Lange, even tho technical adviser Hermann Oberth kept the science straight, as best he could, the plot is a bit pulpy and clunky, still worth seeing tho.)

Stanley Kubrick paid homage to Destination Moon in his film 2001. I had never noticed it. But in their wonderful book THE SPACESHIP HANDBOOK, Jack Hagerty and Jon C. Rogers did! In Destination Moon the space suits are color coded, a good idea! The commander wore Red, the first officer wore Yellow and the rest of crew wore blue.

What color was Keir Dullea’s suit, what color was Gary Lockwood’s and see that blue suit in the POD bay?

Kubrick never said a word about it, but that was like him.

>On the issue of the USSR success, it’s good to remember just how successful–and audacious!– our former foes were in their space program, continuing to this day with very reliable rocket systems and extraordinary engineers.

Unfortunately, for a long time our former and still foes I’m sad to say were understandably less than forthcoming on their failures, with tragic results for both their space program and possibly ours as well.

Let me be specific for this incident remains a grim warning on the dangers of mixing politics and space flight. The story is of the Nedelin Disaster (I first read a full and chilling account in the early 80’s in James Oberg’s “Red Star In Orbit”). The wikipedia entry is here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nedelin_disaster and has many more technical details than Oberg’s account (to be fair, these details were not available at the time to him as according to the article the soon to be former SU did not acknowledge the disaster until 1989). That is correct: the story was covered up for some three decades, though as is the nature of such things a highly garbled account did get out of the Soviet Union almost at once (Personal Note: I recall reading about it in an issue of Science Digest, ~1961).

The former Soviet Union did indeed have great Visionaries and Engineers, but it was all for naught as they were shackled by one of the most repressive governments the world has ever seen. There are many similarities between the Nedelin and Challenger disasters (except for the scale and that is important). Had the SU been open about the disaster, it might have been a very useful data point in our thinking. In my wild fantasy, the Challenger disaster might never had happened.

In 1959, I was lucky to see a presentation in a local library of a Soviet film on the future of space exploration. In a fictionalize sequence (using some first rate modeling work) a rocket virtually identical to the Collier’s illustration above was shown landing on the moon– I didn’t know that at the time, of course. It seemed to me that the Russians had a much clearer and deeper grasp on the future of space travel than America did. But by time of the collapse of the SU, I read how the Russian people had come to despise their space program, viewing the Space Corps as just one more set of privileged people, far removed from the life of the average Russian citizen. They hated it; we find it a bore.

I regret going on about this, but as I would like very much to see a separation of economics and politics, I would also like to see a separation of politics from space exploration. Won’t happen I’m likely to be emphatically informed, but the degree of intermingling has to be kept to a minimum, for the lives of our best and bravest.

I’d rather send a robotic balloon or sailboat to Titan, and it need not be large, just RTG powered for z long mission life.

@ ljk (Larry Klaes, I presume?): nice try.

How big is your worldship plus planetoid? Perhaps over 1,000,000 tonnes for anything that can be called a worldship, but let’s slim it right down to just 4000 tonnes for the present (10 times ISS, about the minimum conceivable size for a manned ship with half a dozen astronauts and shielding against cosmic radiation). If you want a 125-year trip to Alpha Centauri, then that means a cruising speed of 3.5% of c = 10,500 km/s. You presumably want to slow down and stop when you arrive, so a total delta-V of 21,000 km/s.

Assuming an exhaust velocity close to 0.63 of the delta-V, for maximum rocket efficiency, the energy cost for a 4000-tonne ship is 0.77 delta-V^2 per kilogram of vehicle less propellant, thus 1.36 x 10^21 joules (about three times total annual global industrial energy production at the present). TNT is about 4 MJ/kg, so the energy cost translates to 3.4 x 10^11 tonnes of TNT. The largest nuclear weapon ever tested had a yield of about 50 megatonnes (of TNT). Thus the energy budget for this minimal starship (not a worldship) equates to 6800 of the largest nuclear weapons ever built.

However, the 4000-tonne minimal ship is not large enough to be a generation ship, and 125 years is too long for the endurance of a single crew. Either way, it’ll take a lot more bombs than that.

How many bombs does Russia have in its arsenal?

Stephen

Oxford, UK

To continue this line of thought: the entire world (i.e. mostly US and Russia) has about 20,500 nuclear warheads of all types (Federation of American Scientists website). Many of these are tactical, so low yield. If however we assume an average yield of 1 megatonne over all types, then we have 2 x 10^10 tonnes of TNT equivalent in nukes worldwide. This is about a tenth of the energy cost required for the minimal 4000-tonne starship (assuming these bombs provide rocket thrust close to optimum efficiency). (Can someone please give an independent check of these figures? Thanks!)

I believe Walt Disney’s “Mars and Beyond” TV presentation (1959) was based on Von Braun’s concept of a mission to Mars. Here’s a 2-minute YouTube remix with excerpts from that show; it includes the Mars ships, which had the form of a large thin disc mounted on an equally large cylindrical core containing an atomic thruster and a Mars descent and return craft. Here’s the YouTube URL: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsVj6KBEKco

The excellent full DVD of the presentation is available on Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/Walt-Disney-Treasures-Tomorrow-Beyond/dp/B0000BWVAI

from: http://www.nti.org/e_research/e3_atomic_audit.html

“Between 1945 and 1990, the United States manufactured more than 70,000 nuclear bombs…”

This doesn’t include what Russia would have built.

If the US and the USSR were able the manufacture so many weapons for war then surely the world could manufacture a few hundred thousand for the purpose of an interstellar ship.

Increase that 4000 tons to 1,000,000 tons and that would mean manufacturing 170,000 bombs, assuming the ship itself could use something in the 50 megaton range.

Not that I’m in favor of using such an Orion vessel for interstellar travel. For travel within our own solar system thought it would be pretty useful. Use one mega orion, the 8,000,000 ton one with a payload of 3,000,000 tons. It could have lifted 5 smaller orions in the 200,000 tons range and still allowed 2,000,000 tons for other payloads such as bombs to resupply the others. For one launch from earth we would have had 5 vessels that could reach the planets in a decent time plus the use of the mega orion as a space station.

Such vessels could have sent probes to the sun’s focal point and we could now have decent pictures of a few planets around other stars.

Mars and Beyond was the last of the Disney – von Braun collaborations, there were three and that was the last one. There is a special edition of three disks with extra material that came out several years ago. First two featured von Braun and Willy Ley, Man in Space (1955) which was about general spaceflight and the building of a space station, it is an excellent introduction to manned spaceflight. The re-worked ferry ships and station* from The Mars Project appear by way of animation. The second space Tomorrow-Land show was also aired in 1955, with a live action sequence about a circum-lunar flight, technically it’s fascinating but man talk about Popular Mechanics science fiction. Background stuff about the moon was more fascinating. The 1957 Mars and Beyond had von Braun introducing Ernst Stuhlinger and the use of electric propulsion for a Mars Expedition. I heard that von Braun was kind of ‘Marsed Out’ and wanted to show a different idea, so his long time friend and former Peenemünder presented his mission idea. I don’t know if that was ever published anywhere. (Besides von Braun was getting real busy with ‘real world’ stuff.)

*A note: Though the ferry ships are briefly described the Mars Project monograph , they are not detailed, nor was the space station. They are in the novel Project Mars: A Technical Tale, that was not known until 2005!

von Braun and his collaborators had all technical stuff ,in their back pocket, worked out for even the Moon expedition that appeared in Colliers. Tho they and even Chesley Bonestell did some tweaking for that Colliers series.

It always been a shame that the whole 8 issues of Colliers series were never collected into a single volume. There are a couple of stunning Bonestells in those that I don’t think never appeared anywhere else. Plus a lot of exposition that never appeared in the Viking Press books that came from that series. (Not to forget the wonderful Fred Freeman and Rolf Klep illustrations.)

I did not know that the color of the spacesuits in 2001: A Space Odyssey was a tribute to the spacesuit color codes in Destination: Moon – thank you, A. A. Jackson. All these decades later and I still keep learning something new about Kubrick and Clarke’s classic film!

Ironically, if only NASA had followed this idea from those two science fiction films when they first started placing astronauts on the Moon for real, there would not have been the confusion over who was who in the photographs taken during the Apollo 12 mission in November of 1969, the one that landed 600 feet from Surveyor 3.

FYI: Apollo 11 escaped this fate only because Aldrin took very few images of Armstrong – professional jealousy? In any event, we have just two still images of the first man on the Moon while he was being the first man on the Moon, neither of them terribly well done. Tell me how that could have been an oversight! Yes, there are a bunch of other still images of Armstrong from the Apollo 11 mission, but they were stills taken from the various video cameras at Tranquility Base and not from the camera attached to Aldrin’s suit. Armstrong took numerous images of Aldrin with his camera and those are the famous images from that historic mission which are used to represent Apollo 11 to this day.

They resolved this for Missions 13 through 17 by having red stripes on the commander’s spacesuit, but if only they had bright primary colors from the start, that would have been much more dynamically interesting to contrast the lunar explorers with the bland gray lunar surface and black sky. Colorful spacesuits might even have increased the sales of color televisions!

Perhaps NASA or whoever finally sends humans to Mars will have their intrepid explorers in spacesuits with various colors besides white.

Speaking of going to Mars, while commentors here point out how long and boring most space missions will be (complete with YAWNS) or how we just don’t have the technology to send even a small crew to the nearest star in under two centuries, what shall we do exactly to make space exciting to the general public again, so that they will prod their government representatives to keep giving NASA money?

Besides LEO and the Moon, nothing else in the Sol system is closer than a few days away by rocket; a trip to an NEO or Venus and Mars will take months ideally, but no one is seriously considering a manned mission to land on or even orbit the second planet from Sol any time soon. We could promote terraforming a few of these worlds, but that will take centuries to thousands of years as far as the experts are concerned and I don’t think our ears could take the volume of noise from all those yawns that would generate.

Colonizing the Sol system sans terraforming will also take decades and while that will do wonders for the job market and give humanity a promising future, will that also be much too long for Joe Sixpack to tolerate? And will I get to hear my “favorite” phrase of Why aren’t we solving problems on Earth first from this plan?

How about a Dyson Shell? We could start by making a mini-version just with the big rocks in the Planetoid Belt between Mars and Jupiter, which is how Freeman Dyson originally envisioned his plan, with lots of independent colonies encircling Sol rather than one big solid flat shell. It could even be a kind of Niven Ringworld except in pieces instead of a megaribbon. Or will this also fall to the “problems” with Sol system colonization in general?

What I think is going to happen is that if these private space enterprises ever really do get off the ground (wink, wink), some of them may literally go their own ways and at least set up a colony or two in the Sol system. Can’t you just see a religious or political group run by a multibillionaire (or a trillionaire) wanting to live life their way free from the restrictions of the rest of human society on the third rock from Sol? Some of them may die trying, but I bet these are the ones who will ultimately defy the critics and say Adios to Earth and its neighborhood and head out into Parts Unknown.

Maybe the whole galaxy is full of worldships full of those beings who did not get along with the rest of their species and decided to see if the grass (or its equivalent) really is greener around Alpha Centauri.

All I know for certain is, every time some one (especially an expert) says something cannot be done, some one else says “Oh yeah….”

Speaking of 2001’s connection with other SF films, how about this one by Pavel Klushantsev from 1957, titled Road to the Stars:

http://www.dangerousminds.net/comments/before_2001_pavel_klushantsev_classic_road_stars/

and:

http://www.astronautix.com/articles/roastars.htm

Ironically, Kubrick’s early working title for 2001 was Journey Beyond the Stars – which doesn’t make a lot of sense unless the film was going to be about journeying to other universes beyond our own.

@ ljk: The commentator who pointed out here that we don’t have the technology (or the economy) to send even a small crew to the nearest star in under a multiple century journey time would like to suggest further that progress is not always achieved by giving money to NASA, and therefore that making space exciting to the general public, while always highly desirable, is not necessarily a precondition for making any progress at all.

At present, we seem to be doing quite well by seeing NASA starved of the funds it would like to receive. In this way the space agency monopoly on manned access to orbit is on the verge of being broken — and this really is a precondition for further progress into the Solar System and ultimately beyond.

Stephen

I am not against private space enterprise, but we will see if they can raise the resources and funds to make good on their promises. Otherwise it is just going to be suborbital joy rides for the rich or multimillion dollar trips to the ISS for the superich.

And we WOULD have the economy and the technology to venture to the stars if society ever decided to make that a priority, but the way things are going by the time humanity wakes up to the reality that space will be the difference between life and death for our civilization, it will be too late.

I just happened to come across this and immediately wanted to share with all the readers of CD.

A vacation trip to Venus in the year 2500 for one Mr. Smith as imagined in 1950 with art by the master Chesley Bonestell:

http://www.cthreepo.com/writing/bonestell-2.shtml

Of course it may be the year 2500 but everyone looks, dresses, and acts like it is 1950. And Venus is anything but the swampy world full of dinosaur-like creatures. But this is a thing of beauty to behold just the same.

Here is a blog I cannot recommend enough:

http://dreamsofspace.blogspot.com/

July 30, 2012

Wernher von Braun’s Martian Chronicles

From 1952 until 1954, the weekly magazine Collier’s published a series of articles on space exploration spread out across eight issues. Several of the articles were written by Wernher von Braun, the former Third Reich rocket scientist who began working for the U.S. after WWII. The Collier’s series is said to have inspired countless popular visions of space travel. This impact was in no small part due to the gorgeous, colorful illustrations done by Chesley Bonestell, Fred Freeman and Rolf Klep.

Full article and great classic artwork here:

http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/paleofuture/2012/07/wernher-von-brauns-martian-chronicles/