If you’re looking for a new tactic for SETI, the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, Avi Loeb (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) and Princeton’s Edwin Turner may be able to supply it. The duo are studying how we might find other civilizations by spotting the lights of their cities. It’s an exotic concept and Loeb understates when he says looking for alien cities would be a long shot, but Centauri Dreams is all in favor of adding to our SETI toolkit, which thus far has been filled with the implements of radio, optical and, to a small extent, infrared methods.

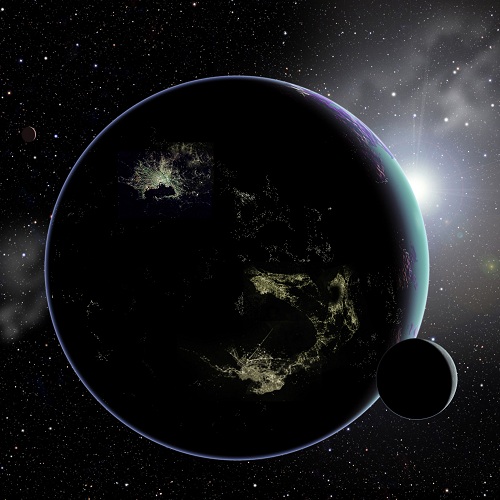

Image: If an alien civilization builds brightly-lit cities like those shown in this artist’s conception, future generations of telescopes might allow us to detect them. This would offer a new method of searching for extraterrestrial intelligence elsewhere in our Galaxy. Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA).

Spotting city lights would be the ultimate case of detecting a civilization not through an intentional beacon but by the leakage of radiation from its activities. In my more naïve days when I just assumed such civilizations filled the galaxy, I imagined someone making an accidental detection of an errant radio signal with a desktop radio receiver, the ultimate ham radio DX catch. As I learned more and came to realize how attenuated such signals would be at these distances, it seemed more likely that we’d need to listen for directed signals, or at best the kind of accidental transmission that might indicate something like one of our own planetary radars.

Then, too, we have to take into account how much our own use of radio has changed, so that because of fiber optic cables and other technologies, we’re lowering our visibility in many wavelengths. An advanced civilization would presumably do the same, but Loeb and Turner figure lighting is something intelligent creatures are going to have no matter what they’re listening to or how they’re listening to it. This is from the recent paper on their work:

Our civilization uses two basic classes of illumination: thermal (incandesent light bulbs) and quantum (light emitting diodes [LEDs] and fluorescent lamps). Such artificial light sources have different spectral properties than sunlight. The spectra of artificial lights on distant objects would likely distinguish them from natural illumination sources, since such emission would be exceptionally rare in the natural thermodynamic conditions present on the surface of relatively cold objects. Therefore, artificial illumination may serve as a lamppost which signals the existence of extraterrestrial technologies and thus civilizations.

The first order of business is to show that searching for artificial lighting is possible within the Solar System, which Loeb and Turner approach by looking at objects in the Kuiper Belt. The technique is “…to measure the variation of the observed flux F as a function of its changing distance D along its orbit.” Working the math, they conclude that “…existing telescopes and surveys could detect the artificial light from a reasonably brightly illuminated region, roughly the size of a terrestrial city, located on a KBO.” Indeed, existing telescopes could pick out the artificially illuminated side of the Earth to a distance of roughly 1000 AU. If something equivalent to a major terrestrial city existed in the Kuiper Belt, we would be able to see its lights.

Objects of interest could be followed up with long exposures on 8 to 10 meter telescopes to examine their spectra for signs of artificial lighting, while radio observatories like the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) or the Precision Array for Probing the Epoch of Reionization (PAPER) could be used to check for artificial radio signals from the same sources. Interestingly, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) survey will be obtaining much data on KBO brightnesses of the sort that could be plugged into Loeb and Turner’s methodology. Thus running a KBO survey as a tune-up of their methods would involve no additional observational resources.

The researchers aren’t expecting to find cities on KBOs, but they do point out that the next generation of telescopes, both space- and ground-based, is going to be able to reach much further into the universe for signs of artificial lighting. An exoplanet can be examined for changes to the observed flux during the course of its orbit. When it’s in a dark phase, we should see more artificial light on the night side than what is reflected from the day side. A signature like this would have to be bright — the night side would need to have an artificial brightness comparable to natural illumination on the day side — but an advanced civilization might have such cities. For now, the Kuiper Belt provides a handy set of targets we can use to test the technique.

The paper is Loeb and Turner, “Detection Technique for Artificially-Illuminated Objects in the Outer Solar System and Beyond,” submitted to Astrobiology (preprint).

For those who want a well-written and researched history of the study of Mars, especially the era of Lowell and his canals, check out this work which is online in its entirety here:

http://www.uapress.arizona.edu/onlinebks/MARS/CONTENTS.HTM

Ljk, you are right in that cranks do much damage in modern society, but it is my belief that they could only attain the requisite popularity level necessary to inflict that damage if the scientific community as a whole is slow to investigate interesting side possibilities.

And yes ljk, science sometimes gets it wrong when freak statistical fluctuations mislead, but such errors are rare. Much more common is that damage done scientists ignoring their own imperfect and very human nature.

Thanks for informing me of Hoagland’s true status, but I fear that to place Lowell in the same category is doing a disservice. Despite his faults, he did much to inspire his generation and start a much needed debate over the suitability of Mars and other planets to life. He also helped to add to the pool of scientific data.

A wonderful treatment of Lowell, Slipher and Tombaugh is the novel Percival’s Planet, which recaptures the era with painstaking accuracy and is a wonderful read all around. I read that Patsy Tombaugh has just turned 100 — grand lady. She appears in the book.

What’s stopping the anomalies community from carrying out their own investigations? The Internet is awash with images and data from old and existing missions. Anyone with a little time, money and know-how can instantly access more images that one can look at in the lifetime. We have hundreds of thousands of images of Mars and the Moon that rival those of Google Maps.

You would think with all that stuff available, someone would make an effort to conduct a systematic search of the archived images using some form of software-based anomaly detection. NASA certainly doesn’t have a monopoly on advanced image processing techniques.

But you know what? The dirty little secret is that they are not interested in doing proper research–the type of research that often takes years of patient, often mind-numbing lab work and analysis to complete–in the first place. No, for them it’s all about instant gratification–download a couple of the latest images from the CNN web site and start looking for straight lines and 90 degree angles, and “Hey Presto!” half-an-hour later you have yourself a derelict spacecraft, a pile of rusty alien tools, or a ruined city complex. That’s much more fun!

Rob Henry said on November 11, 2011 at 18:01:

“Ljk, you are right in that cranks do much damage in modern society, but it is my belief that they could only attain the requisite popularity level necessary to inflict that damage if the scientific community as a whole is slow to investigate interesting side possibilities.”

LJK replies:

I do agree on this point, Rob. I also think the science community needs to do a lot more to educate and excite the public on science. Carl Sagan did much to bring science to the people during his career, such as the Cosmos series and publishing articles in Parade magazine. However, he was also often ridiculed by some of his peers for what they saw as his ego pandering to the public, combined with their view that presenting their field to the public in “prechewed” forms somehow diminished their work. Darned if you, darned if you don’t.

There are more science series on television now, but a lot of them seem focused on fancy effects and sensational topics (“black holes could one day devour the entire Universe!”). I do not even want to talk about the junk that currently permeates The History Channel (“Nazi UFO Conspiracy” was a real title I recently saw on THC). There is even a whole cable channel with the aim of being devoted to science, but sometimes it feels like I am watching a variation on The Discovery Channel, or worse TLC (the latter used to be devoted to actual education). Even Nova, while still a very good program on PBS, has gotten flashier and now has bite-size versions of itself for the short-attention span generation.

Perhaps I just wish the producers of these series would stop spoon feeding things quitee so often and trust that the subject matter itself can be enthralling. Plus, if something does go over the audiences’ collective heads, they might be inspired to look more into a particular topic to satisfy their understanding and curiousity. I have noticed these days that it seems everything has to be explained right up front, rather than letting the viewer think and learn for themselves, or even just to activate their imaginations a little.

“And yes ljk, science sometimes gets it wrong when freak statistical fluctuations mislead, but such errors are rare. Much more common is that damage done scientists ignoring their own imperfect and very human nature.”

Universities and other institutions should do more to “socialize” their members, but I have the feeling we will only be getting mainly token efforts in this effort for a while to come. Therapy is usually only offered or made mandatory when things are getting out of hand, which is often too late.

In the United States at least, needing mental and emotional help is still often seen as a sign of weakness or worse, especially if you are a male. Society pushes every man to be a John Wayne type, whether that actually fits your personality and upbringing or not. As a result, I am amazed things are not even worse than they are. And despite important strides in gender equality made in the last few decades, science is still a male-dominated field.

Rob said:

“Thanks for informing me of Hoagland’s true status, but I fear that to place Lowell in the same category is doing a disservice. Despite his faults, he did much to inspire his generation and start a much needed debate over the suitability of Mars and other planets to life. He also helped to add to the pool of scientific data.”

LJK replies:

As I said before, I do not place Lowell in the same category as Hoagland. Lowell was a smart man who sincerely believed what he thought about Mars and its alleged inhabitants. He also built the proper instruments for his day to conduct research on his subject matter (plus he wrote several well-crafted books on Mars which are still readable by today’s standards and can be found online).

Where the Boston Brahmin went wrong is in the same way every true crank before and after him gets derailed: By clinging to their views despite all the scientific evidence against them. Yes, Galileo went against the established thinking of his day and eventually won, but that was only because the views held by the majority of his era were ultimately flawed, plus the authorities were more interested in keeping their subjects in line than being scientifically accurate.

As for Lowell’s actions doing much for our understanding of the Red Planet, I often wonder if he actually hurt Marx exploration more than he seemed to help. While Lowell and his canals did bring a lot of attention from the general public, the impression left by the man and his work about Mars was as a planet burgeoning with life. Even as most astronomers, professional and otherwise, doubted more and more that any kind of intelligent beings ever lived on Earth’s neighboring world, the vast majority also naturally assumed that Mars was at least covered by creatures similar to moss and lichen and just maybe some more sophisticated and mobile ones (Sagan was a proponent of the latter right up until the Viking mission – see his article on Mars in the December, 1967 issue of National Geographic Magazine).

There were even a few holdouts focusing on the canals, though they often tried to explain their existence with more “natural” reasons, such as long cracks in the surface due to quakes or natural waterways with extensive vegetation growing along their banks which made them visible to terrestrial astronomers during the growing seasons.

When the US probe Mariner 4 flew by Mars in July of 1965 and returned the first close-up images of that world, a lot of people, including the professionals, were shocked to see how barren Mars appeared. Even though Mariner only imaged 1% of the planet from several thousand miles away (and not all that sharply, either), the sight of multiple craters and no canals had Mars almost immediately labeled as being as dead as the Moon. This shock to that collective thinking about the Red Planet was a contributing factor towards the American and Soviet plans for manned expeditions to Mars drying up.

By the time Mariner 9 arrived in late 1972 and showed humanity that Mars was not quite as dead as they thought, at least geologically, any chance for a real manned mission there had already passed. When the two Viking landers touched down on Mars in 1976 and did not beam back clear evidence of even little microbes dwelling in the ground, that sealed the deal for the Red Planet. The Soviets had already stopped their missions to Mars in 1974 and the US would not start up again until almost two decades later.

Maybe this is another darned if you, darned if you don’t situation. Mars needed to be seen as an exciting and literally lively place back in the days when we could only examine it from Earth to build up the necessary interest to get space missions there. Probably nothing less than the hope and thought that intelligent aliens at least used to live there could excite the public and politicians enough to land machines and humans on Mars. The planet has many other very interesting non-organic features that should warrant reason enough to go there, but again the search for life is always the key motivating factor.

We see this too with other worlds on our future target list, such as Titan, Europa, and Enceladus, all of them potential abodes for life. By comparison, note how relatively little attention has been paid to Venus, even though it is a geologically and atmospherically dynamic and exciting world, far more than Mars. However, most people have trouble imagining anything being able to live on that planet, so this along with the fact that it is a rather harsh place to explore means far fewer expedition plans than Mars and other places.

I am certainly not against exploring other worlds for any signs of life. However, I do worry that this focus on finding life over other equally important aspects of a deep space mission could end up harming future expeditions, just as Viking’s lack of obvious evidence for Martian microbes stalled future missions to the Red Planet for decades, even though the Vikings were a very big success in virtually every other aspect.

Bob said:

As a society we need new ways to fund and do science. Right now it is a way too conservative good old boys club hostile to new ideas.

LJK replies:

Okay, how shall we do this? In particular, how do you do real research to find real knowledge outside the parameters of science without ending having exactly the same situations and institutions you are complaining about? I am not asking rhetorically, either.

Bob:

Not sure why you added the phrase “outside the parameters of science”. That was never what I had in mind. I meant more outside the usual culture that surrounds the process of doing science. But here are a few thoughts.

1) End the system of scientific welfare by dependence on government grants.

That means a system dominated by private and corporate money with a minor fraction on the federal government for some area of interest.

2) For government money, oversight by educated non professional’s is a must.

3) New systems of review and publishing is a must.

We need to create an open scientific culture where new ideas are valued and when mistakes are made, people are encouraged to do better rather than shamed and destroyed. What we have now is a flawed system which frightens researchers into not taking enough chances.

There are systems and concepts out there that, for example, explain physics with other models besides standard Quantum Mechanics and they should be allowed to flourish and develop as their own schools of thought.

Science should be more like art. Competing strains or modes of expression. Some will turn out to be wrong. Big deal. Even “wrong” models of nature can be highly useful. Things will advance more in the long run..

Ljk, what a wonderful reply of yours. Surely it merits further discussion.

It highlights that the greatest need is for science to promote itself with both interest to those not technically minded and accuracy. Politicians are forced to try this and excel at using the sound bit. Unfortunately this leads to their policy points being taken just as simplistically as they are given, with the resultant perception being that they lie. This is an outcome would be disastrous for science. So how to solve our dilemma?

One of the staff at my old university was nicknamed “movie star”, because he was so successful at misrepresenting the utility of his work to the media. He did this so blatantly that other members of the scientific community would be clearly able to see that this was just for publicity, and thus they could presumably forgive him. He also covered himself further by pushing for teaching on morals to be part of the science curriculum. But I don’t think that this is the answer.

I have just finished watching a documentary on Trekkies, and am hit by how a sciency tv series can attract a fanatical following, but science NEVER does. To me the answer is to communicate how science is a subject of passionate model building, where small differences to the way data is treated can have great consequences, and both sides of a divide are usually keen for more testing.

The above article is about looking for the light from ETI cities, and examining our ort cloud for such signs is seriously considered. To me this is a beautiful example of how, in science, testing a model is more important than an a priori assumption of how closely that model is likely to resemble the reality, and how proponent of such a test can, at times, have no expectation of success, but be more interested in developing tools for other investigations. It is also a wonderful example of how science can test every limit, and how “failure” of a hypothesis is not failure in the everyday sense that a crank would have it. It is really just an increase in our knowledge and a chance to move on to an new adventure.

Thank you for the compliment, Rob Henry. Now to return the favor on your latest post here.

Regarding the sometimes sad fact that science fiction has way more groupies than science fact, I recall from my early fanboy days with Star Trek how I would try to engage some of my fellow fanboys in discussions on the space science and technology depicted in the series, only to discover that they were not interested in such things.

Instead, for them, Star Trek and all similar SF series were the equivalent of soap operas set in space. This explains why so many of their science gaffes were often overlooked and why those technology depictions which bordered on magic were rarely if ever questioned.

By the way, I highly recommend the 2009 film Fanboys, about a group of rabid Star Wars fans who decide to infiltrate George Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch to see The Phantom Menace before everyone else (the film’s setting takes place in 1998). They got the culture down pretty good and the encounter with some Trekkers in Iowa (where James T. Kirk will be born some day, natch) is great.

About “city” lights in the Oort Cloud/Kuiper Belt: While I know this was mainly a thought experiment for the authors of the paper, would an ETI inhabiting those distant iceballs ever be blatant enough to make themselves visible in such a fashion? Perhaps they may rightly assume that since humans cannot get their acts together when it comes to putting a base on the Moon or Mars, the humans won’t be able to get more than an investigative robot probe out their way, and that alone will take decades to happen.

However, since beings with the will and ability to travel all the way to the Sol system will be thinking in very long terms, they may also rightly assume that humanity will one day get its act together enough to start properly colonizing the Sol system and become sophisticated enough to properly investigate the strange lights at the fringes of their celestial territory. Therefore, it would remain prudent for these KBO/OC ETI to remain incognito unless they wanted contact from future humanity.

Leading back to the original point of the paper and this blog topic, the entire premise of our detecting ETI depends on whether other technologically advanced beings also pollute their skies with excessive and expensive lights. If they are similar to us in this manner, either through ignorance or indifference, we should also consider whether to contact such beings when the time comes, or wait until they have matured if this scenario even applies here.

The same may be thought of us by others in the galaxy, who could see our urban lights both as excessive and a severe lack of awareness and concern over being detected on a galactic scale. In any event, they block the stars for millions of humans on Earth and thus reduce the interest and incentive to explore those very objects.

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Is there Life or Water on Mars?

Posted by Darin Hayton on 09/27 at 10:42 PM

Mars and its possible water seem to be a perennial topic for astronomers since 1877 when the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli first noticed “canali”—a network of straight lines across the surface of the planet. Although Schiaparelli did not infer from these that the planet was inhabited, for the next thirty years his canali sparked the imagination of numerous astronomers and popularizers. Even today astronomers continue to argue about whether or not the evidence indicates flowing water on the Mars. Most recently, in August and then September two separate articles appeared arguing for and against water on Mars.1

In the early 1890s Percival Lowell was looking around for a new hobby to occupy his time and wealth. He had spent much of the previous decade traveling around and writing about the far east, especially Japan. After reading Camille Flammarion’s La planète mars, Lowell decided to dedicate his fortune to studying the planet in an effort to demonstrate that it was inhabited by intelligent life.

In 1894 he established his astronomy in Flagstaff, AZ just in time to study the planet during its next opposition. He immediately wrote a popular book on Mars, Mars (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1896) in which he claimed that the canal structures he saw on Mars were evidence of intelligent life. Further, he claimed that the planet was slowly dying, and that these canals were efforts by the Martians to irrigate their planet during the summer months, when the polar icecaps melted.

Two years later Lowell published the first book-length scientific study of the canals of Mars, The Annals of the Lowell Observatory, vol. 1 (1898).

Full article here:

http://www.pachs.net/blogs/comments/is_there_life_or_water_on_mars/