Given yesterday’s post on wandering planets, otherwise known as ‘rogue’ planets or ‘nomads,’ today’s topic falls easily into place. For even as we ponder the possibility of 105 rogue planets at Pluto’s mass or above for every main sequence star in the galaxy, we confront the fact that we still have much to learn about objects much closer to home in our own Kuiper Belt. We have yet, for example, to have a flyby, although it’s possible the New Horizons spacecraft will line up on a useful target after its encounter with Pluto/Charon (and yes, it’s conceivable that Triton is a captured KBO, and thus we have had a Voyager flyby). The discovery of objects like Sedna, Makemake and Eris makes it clear how much we may yet uncover.

We can think of the broader category of Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) in terms of potential mission targets, but we should also ponder the fact that their strong dynamical connection with the planets can help us gain insight into the mechanics of Solar System and planet formation. This is what Scott Sheppard (Carnegie Institution of Washington) and colleagues have in mind as they present the results of a southern sky survey for bright Kuiper Belt objects. Centauri Dreams reader Joseph Kittle gave me the heads-up on this interesting work, which notes that the Kuiper Belt, as a remnant of the original protoplanetary disk, contains what the authors call a ‘fossilized’ record of the original solar nebula and the development of the Solar System.

We’ve had earlier TNO surveys of northern hemisphere skies using the Palomar 48-inch Schmidt telescope (hence the discovery of the aforementioned Eris, as well as Haumea, Quaoar, Orcus and others). But the southern hemisphere has been tougher to survey because of the lack of wide-field digital imagers on suitable equipment there. It was the installation of just such an imager at Las Campanas in Chile that allowed the OGLE-Carnegie Kuiper Belt Survey (OCKS) to take place, one of the first large-scale southern sky and galactic plane surveys aimed at detecting bright Kuiper Belt Objects beyond the orbit of Neptune using state of the art digital CCD detectors. A second survey began in 2009 using the Schmidt telescope at La Silla.

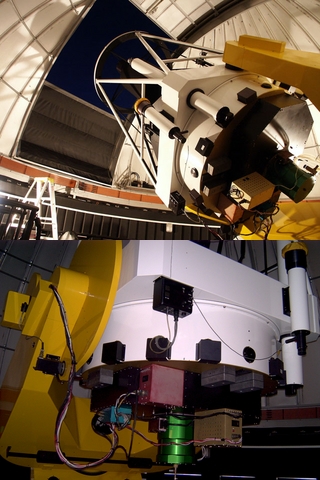

Image: The University of Warsaw’s 1.3-meter telescope at Las Campanas, used in the OGLE-Carnegie Kuiper Belt Survey. Credit: OGLE/University of Warsaw.

Eighteen outer Solar System objects were detected in the survey, including fourteen that were new discoveries, an indication of how little this region of the sky has been searched for TNOs in the past. It’s interesting here to recall the definition of a ‘dwarf planet,’ defined by the IAU as an object that is in hydrostatic equilibrium and has not cleared the neighborhood around its orbit of other objects of similar size. It’s an imprecise definition, say the authors, but Pluto and Eris are clearly dwarf planets, while Makemake and Haumea most likely also qualify, and we’ll probably find that Sedna, 2007 OR10, Orcus, and Quaoar fit here as well.

The trick is figuring out what the lower size limit of an object in hydrostatic equilibrium really is, with some research indicating it could be as small as 200 kilometers in radius. That would put many more outer system objects into contention as dwarf planets, including three that were discovered in this survey, although at present the actual size and shape of these bodies will require further work to pin down with precision. Newly discovered 2010 KZ39 is particularly interesting, a possible member of the Haumea family based on its orbit. The authors have this to say about larger bodies in what we can call the classic Kuiper Belt (internal citations omitted for brevity, but of course you can find them in the online paper):

The actual number of Pluto-sized bodies is now known. Previous authors have argued that the Kuiper Belt likely lost a substantial amount of its mass through collisional grinding and dynamical interactions with the planets. Observationally, many more objects appear to be required in order to produce the observed angular momentum of the largest KBOs and binaries. Detailed simulations show that Kuiper Belt formation is possible with only the small number of Pluto-sized objects observed. A significant number of Pluto sized objects likely exist in the populations beyond 100 AU such as the Sedna types and Oort Cloud objects, which are currently too faint to be efficiently detected to date. It is important to determine if the Pluto-sized objects formed in the Kuiper Belt as we see it today or if they originated much closer to the Sun and were later transported to their current orbits.

So take note: Beyond the Kuiper Belt itself, there may exist at several hundred AU or more other large objects even of Pluto or Mercury-size, and perhaps large objects in Sedna-like orbits. The OCKS survey found no Sedna-class objects within the 300 AU region to which it was sensitive, and it may be that a survey like Pan-STARRS will have a better chance to detect such objects because it has the capability of working with fainter magnitudes than OCKS. We’ll also need the services of the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope to probe the TNO population more deeply.

It’s heartening to ponder the authors’ conclusion that we are making serious progress on the Kuiper Belt, with complete surveys now for objects 80 kilometers in radius out to 30 AU, and 225 kilometers in radius out to 50 AU. Beyond a few hundred AU, much remains to be done. Given the gaps in our knowledge as we move out toward the inner Oort Cloud, it’s clear how many discoveries await us in this region of space comparatively close to home compared to the interstellar distances we one day hope to travel. The relatively simple vision of the Solar System many of us grew up with has rapidly given way to a system surrounded and permeated by rocky and cometary debris, with dwarf planets in unknown numbers far from the central star.

The paper is Sheppard et al., “A Southern Sky and Galactic Plane Survey for Bright Kuiper Belt Objects,” Astronomical Journal 142, (October, 2011) p. 98 (preprint).

It is unfortunate in this day and age that the Southern Hemisphere does not have more astronomical resources, as it often seems that some of the most interesting sky stuff happens in that part of Earth facing the heavens.

Comet McNaught in 2007 is one such celestial body that comes to mind: It made a spectacular display for those south of the equator but hardly registered for anyone who did not follow astronomical Internet sites up north. Plus they’ve got the Magellanic Clouds and the Alpha Centauri system. It’s just not fair sometimes.

Given so much real estate out beyond Neptune, that part of the Solar System seems a logical place for large scale development in a couple of centuries.

I wonder how many of these KBOs will overlap with the ones discovered with the Zooniverse Ice Hunters project.

The outer Kuiper belt is a very strange place; was affected by something in the distant past (of which Sedna is currently the only known witness). There’s a great description in Mike Brown’s blog:

http://www.mikebrownsplanets.com/2010/10/there-is-something-out-there.html

I am wondering if KB or Oort cloud objects could be detected by observing stellar eclipses? Somewhat like microlensing in reverse. The galactic core would be the perfect background for that. Are eclipses just too rare?

I just found out today that there will be a follow up project to Ice Hunters, through which citizen scientists will be able to participate in KBO hunting. It will be called Ice Investigators and should be unrolled within the next several months.

The region known as the Kuiper Belt actually has three regions–the resonance area, where Pluto and the small bodies that share resonances with Neptune orbit; the Kuiper Belt proper, where the majority of KBOs are located; and further back, the Scattered Disk, where Eris is located. Scattered Disk Objects (SDOs) have orbits that are much more elliptical than than objects in the resonance area or in the Kuiper Belt proper. Sedna is actually believed to be an inner Oort Cloud Object (OCO).

I actively discuss KBO discoveries in my blog, with the most recent prior to the ones announced today, here:

http://laurelsplutoblog.blogspot.com/2011/08/and-babies-make-16-solar-system-planets.html

I’ve often wondered if a rogue planet wandering near Sol could ever be the target of a far future space mission. There’s the possibility that such a planet would be warm enough to support bacterial life, and who knows exactly what the astronauts might find?

What’s the probability of a rogue planet wandering within relatively easy reach? Does anyone know? If the nearest rouges are so far away that we have to cross trillions of miles to reach them, then we probably won’t visit them until we have developed some form of interstellar travel. If one comes a lot closer, maybe a manned expedition could reach it before then- if it was an interesting enough destination.

There’s a funny “error” in the preprint: Table 3, titled “Ten Intrinsically Brightest TNOs”, only lists nine TNOs. Number 10 would probably be their “rediscovered” 2007 JJ43.

We can pretty much count on seeing some new dwarf planets as the scopes reach out farther. But the strength for the sunlight drops off with the square of the distance so even very large objects are pretty faint. we need the big scope to do this or to improve infrared observation by a couple of orders of magnitude,, and down to cooler object spectra.

@jkittle, it is more to the point that the strength of sunlight reflected back to Earth drops with the fourth power of distance.

Rob

I think your math is right on that.

based on the stability of the resonance orbits of the the known kuiper belt objects there is probably nothing really lareg int he plane of the elliptic for about to about 100 Au which is also the observation limits for planets with reasonable abedo. Panstarrs should push the search out farther, they are due to have some fairly complete parallax and motion data on a lot of object by the end may or june once tome candidate are located the really big scope will come in and nail down the orbits and start to put limits on the sizes. I think there is a t least a mars size object out there, based solely on hope and the history that we find something new and interesting everytime we expand our ability to see. LSST will have a ten year mission that will push the search out out to past 500 AU

@ljk

It is very nice to see bright yellow Alpha Centauri and the Magellanic Clouds every night, we also got some great photos from Waiheke Island of Comet McNaught setting over Auckland. Every sky observer should plan an observing season in the Southern Hemisphere before they die, the skies are breathtaking.

Joy, the one time I spent some time in the southern hemisphere I was totally confused by the night sky since I recognized absolutely nothing, and so could not get my celestial bearings. I could find most anything in the north, though that was about it. Very pretty, but without a chart it was uninformative. It was bad enough dealing with an upside-down Moon (and Orion) and seeing the Sun in the north! I probably saw A Cen though I wouldn’t have known it (including the times I’ve been in the tropics).

So now we finally know that Pluto is the largest Kuiper belt object, don’t we? (Barring a larger object in the tiny regions not surveyed.) Last year Mike Brown (http://www.mikebrownsplanets.com/2010/10/heading-south-looking-up.html) would not rule out a Pluto-sized (or even larger) object hidden in the yet un-surveyed Southern hemisphere, since the South “didn’t even have a Tombaugh”. I wonder if his own (ongoing) Southern sky survey adds some more dwarf planets to the list in the near future…