I closed last week with two posts about the AVIATR mission, an unmanned airplane that could be sent to Titan to roam its skies for a year of aerial research. It’s a measure of Titan’s desirability as a destination that it has elicited so many mission proposals, and I want to get into the Titan Mare Explorer (TiME) as well, but let’s pause a moment to consider the nature of what we’re doing. Out of necessity, all our missions to the outer system have been unmanned, but as we learn more about long-duration life-support and better propulsion systems, that may change. The question raised this past weekend in an essay in The Atlantic is whether it should.

Ian Crawford, a professor of planetary sciences at Birkbeck College (London) is the focus of the piece, which examines Crawford’s recent paper in Astronomy and Geophysics. It’s been easy to justify robotic exploration when we had no other choice, but Crawford believes not only that there is a place for humans in space, but that their presence is indispensable. All this at a time when even a return to the Moon seems beyond our budgets, and advanced robotics are thought by many in the space community to be the inevitable framework of all future exploration.

But not everyone agrees, even those close to our current robotic missions. Jared Keller, who wrote The Atlantic essay, dishes up a quote from Steve Squyres, who knows a bit about robotic exploration by virtue of his role as Principal Investigator for the Spirit and Opportunity rovers on Mars. Squyres points out that what a rover could do even on a perfect day on Mars would be the work of less than a minute for a trained astronaut. Crawford accepts the truth of this and goes on to question what robotic programming can accomplish:

“We may be able to make robots smarter, but they’ll never get to the point where they can make on the spot decisions in the field, where they can recognize things for being important even if you don’t expect them or anticipate them,” argues Crawford. “You can’t necessarily program a robot to recognize things out of the blue.”

Landing astronauts is something we’ve only done on the Moon, but the value of the experience is clear — we’ve had human decision-making at work on the surface, exploring six different sites (some of them with the lunar rover) and returning 382 kilograms of lunar material. The fact that we haven’t yet obtained samples from Mars doesn’t mean it’s impossible to do robotically, but a program of manned exploration clearly points to far more comprehensive surface study. Crawford points out that the diversity of returned samples is even more important on Mars, which is more geologically interesting than the Moon and offers a more complicated history.

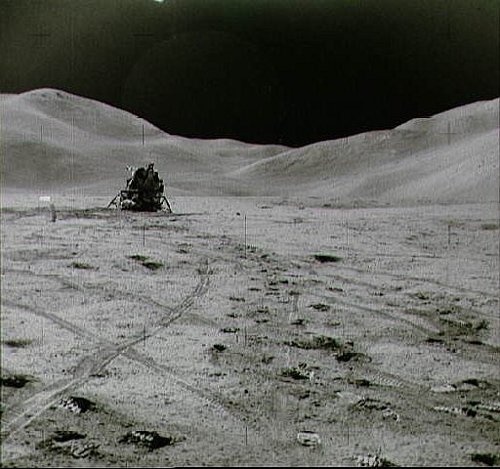

Image: Apollo 15 carried out 18.5 hours of lunar extra-vehicular activity, the first of the “J missions,” where a greater emphasis was placed on scientific studies. The rover tracks and footprints around the area give an idea of the astronauts’ intense activity at the site. Credit: NASA.

Sending astronauts by necessity means returning a payload to Earth along with intelligently collected samples. From Crawford’s paper:

Robotic explorers, on the other hand, generally do not return (this is one reason why they are cheaper!) so nothing can come back with them. Even if robotic sample return missions are implemented, neither the quantity nor the diversity of these samples will be as high as would be achievable in the context of a human mission — again compare the 382 kg of samples (collected from over 2000 discrete locations) returned by Apollo, with the 0.32 kg (collected from three locations) brought back by the Luna sample return missions.

It’s hard to top a yield like that with any forseeable robotic effort. Adds Crawford:

The Apollo sample haul might also be compared with the ? 0.5 kg generally considered in the context of future robotic Mars sample return missions… Note that this comparison is not intended in any way to downplay the scientific importance of robotic Mars sample return, which will in any case be essential before human missions can responsibly be sent to Mars, but merely to point out the step change in sample availability (both in quantity and diversity) that may be expected when and if human missions are sent to the planet.

Large sample returns have generated, at least in the case of the Apollo missions, huge amounts of refereed scientific papers, especially when compared to the publications growing out of robotic landings. Crawford argues that it is the quantity and diversity of sample returns that have fueled the publications, and points out that all of this has occurred because of a mere 12.5 days total contact time on the lunar surface (and the actual EVA time was only 3.4 days at that). Compare this to the 436 active days on the surface for the Lunokhods and 5162 days for the Mars Exploration Rovers. Moreover, the Apollo publication rate is still rising. Quoting the paper again:

The lesson seems clear: if at some future date a series of Apollo-like human missions return to the Moon and/or are sent on to Mars, and if these are funded (as they will be) for a complex range of socio-political reasons, scientists will get more for our money piggy-backing science on them than we will get by relying on dedicated autonomous robotic vehicles which will, in any case, become increasingly unaffordable.

Will the Global Exploration Strategy laid out by the world’s space agencies in 2007 point us to a future in which international cooperation takes us back to the Moon and on to Mars? If so, science should be a major beneficiary as we learn things about the origin of the Solar System and its evolution that we would not learn remotely as well by using robotic spacecraft. So goes Crawford’s argument, and it’s a bracing tonic for those of us who grew up assuming that space exploration meant sending humans to targets throughout our Solar System and beyond. That robotic probes should precede them seems inevitable, but we have not yet reached the level of artificial intelligence that will let robots supercede humans in space.

The paper is Crawford, “Dispelling the myth of robotic efficiency: why human space exploration will tell us more about the Solar System than will robotic exploration alone,” Astronomy and Geophysics Vol. 53 (2012), pp. 2.22-2.26 (abstract). Thanks to Joseph Kittle for calling this paper to my attention.

“Robotic explorers, on the other hand, generally do not return (this is one reason why they are cheaper!)”

This is an interesting point that I haven’t seen emphasized in this debate before. If you are going to do a sample return mission, one of the big reasons for the cheapness of robots goes away.

Probably the best reason to send humans into space is that people tend not to get excited about robots roving around collecting rocks compared to, say, Alan Shepard playing golf on the Moon. Without the human element, space will continue to seem totally forbidding and desolate, and therefore not worth exploring. Facility at collecting rocks isn’t a sufficient justification for sending humans to other worlds. Plant flags, play golf, build monuments, meditate under the stars, recite poetry, set off fireworks — just do something inspiring up there!!

@Bob “If you are going to do a sample return mission, one of the big reasons for the cheapness of robots goes away.”

The cost of human exploration is the much larger hardware requirements, including life support that is needed. Robots can explore for a long time without succumbing to radiation damage that harms a human. We cannot easily explore the closer Galilean worlds of Jupiter due to radiation. Even Mars requires burying the hab to reduce exposure.The trick, I think, is to:

1. use robots where humans cannot go

2. use robots to expand human effectiveness, e.g. autonomously seek out places to inspect.

3. keep the human brain in close proximity to the robot to allow real time operations. A human in Mars orbit, controlling a robot on the ground via VR, is going to offer some benefit over a remote human on Earth, and teh much higher cost of landing a human on Mars to do the same tasks locally.

It will be an interesting race between the advancement of AI and human life support. What if we could indeed upload brains and have them stay sane in a machine body to explore?

Robots can, and have returned samples from the moon (Luna 20, Luna 24), comets (Stardust), the sun (Genesis), etc. Maybe small samples (even miniscule), but samples all the same.

As I recall, the lunar samples were done best when they trained astronauts to be effective field geologists. Otherwise they were just picking up random material.

Do we know what the relative cost of the manned and unmanned return missions were? The manned missions had about 1000 times the diversity and amount of material. Did they cost less than 1000 times the unmanned missions?

If they cost more than that, the paltry returns are not because unmanned missions are a bad idea, but because we have spent a lot less on them.

In the article, I did not see much of an explanation of why a manned mission is better. There is the unsupported statement that “what a rover could do even on a perfect day on Mars would be the work of less than a minute for a trained astronaut”, which seems dubious to me. I would find a factor of two to ten times more efficient plausible, but a factor of 1440 (the number of minutes in a day) requires more than just a single statement.

An unmanned missions should be able to send more equipment and return more samples for the same cost. By removing the astronauts, you gain several hundred pounds of weight just by not having the bodies there. You also save on the weight of the life support systems and any shielding that humans would need but robots would not. The weight of the robot needs to be balanced against these savings, but it seems that we should be able to build a robot that has the mobility and collecting abilities of a human but weighs less than the human and its support system.

I think the argument “Send up somebody to hit a golf ball! Play an iPod! Dance a Jig! Flash an asteroid! INSPIRE PEOPLE!!!” is the kind of argument that gets whole gobs of space missions cancelled. Could we just have a rational debate and try to inculcate in the broader public a real sense of the costs and benefits of the various approaches? It’s NASA’s job to do science and discover stuff, not to pander and entertain the viewing public. Why are the Department of Agriculture, say, or GSA, or Dept of Justice, or Defense, not obliged to constantly inspire the next generation (e.g. constantly appeal for their budget not to be gutted?)

@Troy “The weight of the robot needs to be balanced against these savings, but it seems that we should be able to build a robot that has the mobility and collecting abilities of a human but weighs less than the human and its support system.”

And the robot collector need not return either. Just the samples in the ascent and return ships if the robot collector is a separate vehicle.

Interestingly, Nasa had all sorts of plans for complementary human-robot exploration of the moon. But as one wag put it, the humans might end up spending all their time fixing the broken machines, which might suggest robots are not always a good thing.

I personally think there are good and appropriate roles for both. But it is hard not to understand the desire for humans to participate at the sharp end. We recently saw this with Cameron’s dive onto the Marianas Trench. Arguably this was a stunt that could have been much more cheaply (and safely) done with an ROV. Certainly Cameron didn’t do anything extra that validated his presence.

Unless something significant happens to cheapen human spaceflight, the steady improvement in AI, automation and miniaturization should favor increasing robot exploration.

The best way to thoroughly explore the surface of both the Moon and Mars, IMO, is to combine telerobotic explorers with permanently manned facilities. Robots teleoperated by humans in real time back on Earth could be deployed from permanently manned outpost on the lunar surface. Using batteries and solar power, such telerobots could probably travel to any point on the lunar surface and back within 100 days, taking videos and digital pictures while also returning collected samples back to the lunar outpost for later return to Earth with the astronauts.

On Mars, robots could be teleoperated in real time by humans located either at a space station in Mars orbit or by humans located at a Martian outpost on the surface. Teleoperated robots on Mars, however, could consist of both rovers and those being transported by air aboard hydrogen balloons. Again, rock and soil samples could be returned to the Mars outpost and eventually returned to Earth along with astronauts being routinely returned to Earth.

Due to the need to minimize the full exposure of humans to deleterious levels of cosmic radiation, the physical exploration of the Moon and Mars by humans will always be limited with humans, at least 90% of the time, being mostly confined to appropriately water or regolith shielded bases or outpost. So permanent outpost in combination with teleoperated robots would greatly enhance human exploration of the Moon and Mars.

Marcel F. Williams

Let’s be practical. Right now the U.S. only spends .6% of the national budget on NASA. This is nowhere near enough to send an effective exploratory mission to the Moon, much less Mars or a Jovian moon. If we’re going to get serious about space exploration, we have to make a real effort to fund it.

Neil deGrasse Tyson:

Priorities, Plans, and Progress of the Nation’s Space Program

Russell Senate Office Building

Washington DC

March 7th 2012

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ndhxdDgSgI

@Troy “If they cost more than that, the paltry returns are not because unmanned missions are a bad idea, but because we have spent a lot less on them.”

Certainly the debate is straightforward if it’s an issue of only money and safety; robots win hands down. I as a doctor am only interested in seeing to the astronauts’ well being as they spend more time in space further from Earth. To justify human exploration you need more than simple materialistic logic. You need tangible and immediate high value returns as incentives. Commerce played an important role in powering the expansion of naval power in the past. Commerce can and is doing the same thing now. Of course people like me will be around to make sure the technology is ready to sustain human health and well being in space. Politics can play a role too but maybe for only a like in the Apollo program; For king and country :-) .

“Sending astronauts by [necessity] means returning a payload to Earth along with intelligently collected samples.”

It is well and good to have the ability to return your people to their home world. Good idea, should they want to. However, I have noticed that this concept is repeatedly intimated to such extent that it seems to be stated in the hope that it may become some sort of law. And if it is not possible to return your citizens, then some kind of crime against humanity has just occurred. I disagree with the notion or ‘law’ that one must be returned and would like to point out that there are many who would willingly go on a one way colonisation expedition never to return. Having the ability to be returned is comforting but I’ll bet my bottom dollar that it will be declined, no matter the hardship or conditions, by those who hold a contrary view of ‘PC laws’, safety nets or what the public thinks it should respond with as the correct response to the concept, so they don’t get a frowny-face vs. a smiley-face on THEIR public opinion report card.

It almost seems when I read of human space exploration, all I garner from the papers is opinion(s) that say: ‘No! We can’t do that!’ ‘It’s impossible!’ ‘It will take another 500 years!’ Or maybe even as comical as fishing on a lake and saying: ‘No! we ain’t gonna do it until we know how to build an aircraft carrier.’ … All of which will probably be the case, since more effort is put into weapons of mass destruction instead of wanting to own the solar system.

<:3)~~

In order to get a ballanced aproach to the humans-versus-robots qustion as concerning spaceWORK , the robots real advesary , the real hot blodded alternative to the robots should should be considered and understood . And that is not the kind of armchair warriors that most of us here probably are , even if we might be capable of fixing the lawnmowwer now and then . It is more like the kind of guys who do all the dangerous but extremely profitable work at oil rigs , underwater pipelines , salvage operations , and then of course the astronauts when they are not unemployed . Human funktioning of this kind is mostly a teamwork , but always connected to the individuals decionmaking ability on a nonverbal intuitive level ,which doesnt go very well with many long years of formal theoretical education in an EARLY age.

It is therefore a dangerously wrong situation if decions concering “robotization” are left to a group of “normal” welleducated peoble who have never personally experinced the real and sometimes incredible power of the “other” kind of of humans .

Before the ISS was build , I remember a panel of experts reaching the conclution that the asemblywork was way beyond human fysical ability..

Missing from this article is the cost of Luna v.s. Apollo. I see some interesting numbers on wikipedia, but I don’t fully trust it at this point. If true, 5x the cost for Apollo is way way worth it, considering the amount, quality and diversity of samples returned….. That’s just looking at the samples. That kind of ratio may not hold true for more massive bodies, or harsher environments, but clearly in my mind, boots on the ground was the best choice for the moon in that situation.

The other interesting thing on the moon, would be the lunar prospector mission, which is better as a robotic mission. We need both, and use each where most effecient. Generally, probes to form a summary, robots/probes to setup the interesting questions and locations, and humans to answer those questions in detail.

(ps Cameron’s dive is telling, since we probably send robots down there all the time and nobody knows or cares. Soon as you put a person down there, kids are doing reports, it’s in the news cycle, other projects are probably getting funding/started.)

the time it takes to send a signal really limits the types of interactive science that can be done by, say, the new horizons mission. Only distant pictures will be available as the mission specialist plot their final path though the Pluto system and decide where to point the cameras and for how long. It is fair to say that the farther away a system is the more you need humans nearby to make up for the communications lag. If you have orbital mission s like Cassini or dawn, you can do a lot more, but it is still SURVEY work, not” lets follow up on this interesting observation”. it is my experience you need to be able to do both. Right now all the ( Wonderful) solar system science being done from space platforms is survey type work, not investigator- initiated inquiry. The rewards for the latter will be great because of the tremendous built up potential. imagine all the great work that could be done on the moon with the new digital and instrumental analysis available. we even have better means to target the landign sites.

Finally, will we be able to move beyond earth looking for habitats? Not there to investigate only but also looking for places to call home?

I am confident the solar system will be explored and eventually inhabited, but not convinced on its timeframe- maybe hundreds or even thousand of years form now- or maybe in the next 50 years.

As for interstellar flight, it will depend on 1) finding a set of conveniently located targets at less then 500 AU, at less than one light year and then perhaps a t 2 light years maybe these will be rogue planets or large dwarf planets. maybe even a very cool brown dwarf or two. barring that we can always hope for “new physics ” to make FTL ( or CTL Close to Light) speed possible. Right now, Honestly we are looking at a realistic limit of about 0.01% of light as the speed limit folks!

@Troy

When is the last time you tried to do the job of a trained geologist with one hand bound behind your back, half your fingers cut off, no sense of touch, your legs replaced with wheels (that keep getting stuck in the %$#@ dust), and to top it all off, less intelligence than a retarded, lobotomized cockroach?

The day a robot can outperform a geologist at rock collecting is the day they can build me a robot girlfriend that is virtually indistinguishable from a flesh and blood woman. Don’t forget that robots have not intelligence, creativity, or ability to reason. They just do what we program them to do. They can’t respond to unusual circumstances or recognize something they haven’t been programmed to respond to as being important.

Nor can you send a robot to a university and have it obtain a Phd in geology. Picking up interesting specimens involves more than just digging, after all. Astronauts who haven’t been trained as field geologists just pick of random specimens, and robots can’t do any better. Don’t prattle on about A.I., either- they have yet to demonstrate that machine intelligence is possible, and even if it is, they aren’t anywhere close to building one at NASA!! We’re talking real technology here, not the techno-fantasies of computer scientists.

Telepresence is one possible way to collect samples without sending an actual astronaut. However, there is still question as to whether controlling a robot from a distance will feel close enough to actually being there, and aside from that, the time lag for Mars is just too long. Leaving an astronaut in Mars orbit is just stupid- why leave her pink fleshy body exposed to radiation and solar storms just to pilot a stupid robot when she could land on Mars, take shelter from radiation, and just do the job herself?

@Alex Tolley

“3. keep the human brain in close proximity to the robot to allow real time operations. A human in Mars orbit, controlling a robot on the ground via VR, is going to offer some benefit over a remote human on Earth, and teh much higher cost of landing a human on Mars to do the same tasks locally.”

This is what I see happening as far as colonizing mars.

We won’t be going any where until advanced tele-presence robots can be made. Ones with dexterous hands. Perhaps not quite advanced as the ones in the movie “surrogates”.

Then land a bunch of them (6+) along with earth digging machines and have them build a large underground habitat. They would be controlled by humans in orbit would would then relocate to the surface it was completed.

They need dexterous hands in order to repair each other.

Longer term, most of the work out on the surface would be done by robots controlled via tele-presence by humans staying within their habitats underground.

I just don’t see humans in spacesuits working 12hr shifts outside digging and building habitats. The risks from radiation exposure and suit failures is too high long term.

Paul, the title of your piece does not quite match its contents. Ian Crawford is talking about scientific exploration, which clearly benefits from robots in some ways and astronauts in others, and comes down to what money is available for what science. But the question of “reasons for a human future in space” is a very different debate.

I would suggest that the fundamental reasons for a human future in space are, firstly, that our civilisation is based on economic, technological and population growth, and, secondly, that almost all the opportunities for continued growth are extraterrestrial. If our civilisation survives, then almost all our descendants will live permanently away from Earth, and almost all of them will live in artificial space structures rather than on planetary surfaces, in this and other solar systems.

The question is therefore more a political one: whether an industrial civilisation with its associated freedoms and material wealth can survive for long on a single planet. I would suggest that on a timescale on the order of centuries the risks of a major setback to our whole way of life may become unacceptably large, and continued growth is the only way forward at this stage. So we face either large-scale space colonisation, of the decline and fall of the democratic-industrial empire.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

The US should have continued the Saturn V production line,

establish a manned base at the lunar poles,

with mining, smelting, and mass drivers

sending building materials for huge GEO stations,

with high power com sats, cell-phone sats, and weather-control sats,

returning the original cost many-fold.

The profits could fund hundreds of unmanned missions into the solar system.

All this could have been done with the money blown on Great Society,

and by now a 100,000 people would be in space,

and tornados would be no more.

By now, we wouldn’t be worrying about how to fund space science but how to enjoy the immense wealth flowing down.

But no, the Left has always hated the space program because it is an inefficient way of buying votes, whereas welfare handouts work splendidly: that’s why you always hear the Left bleating about

‘spending all that money here on Earth’.

I’m not a “trained geologist”, but being a dedicated “rock hound” when I go exploring in some of the harshest places in outback Australia, I’m still doing more than just picking up “pretty rocks”!

Maybe I’m wrong, but most people can tell the difference between sedimentary, igneous and metamorphic rocks!

Just like most people can spot an obvious fossil!

Besides some really nice crystals, I have a great collection of fossil sponges, coral, tube worm casts, an ammonite or 3 and a few fern fossils.

You don’t need a geologist to dig a trench to look at soil horizons or take a core sample.

Robotic missions have a cool factor, but “boots on the ground” are what is needed.

These notions of tele-operated moon missions being controlled in real time from lunar orbit a kinda “whack”!

How would that actually work?

Are you going to have a ship or station in a “selene-stationary” orbit over your study area?

No, because it’s not possible.

It would take a network of relay satellites orbiting the moon, with at least one of them manned.

Think of the extra expense that would involve.

The same goes for a Mars mission.

Can you actually have a “geosynchronous” orbit around Mars?

I think an important point for a manned Mars mission would be to make the exploration as simple and as manual as possible.

For one thing a bit of toil would help with muscle and bone loss of the trip there.

No one will know if it is possible to, for example, dig a trench by hand in one third gravity, unless we try it.

Even an “untrained” explorer like myself would see things a robot would miss.

Even simple things like how compacted the soil is just from how much effort it required to break up the crust would be important information.

Let alone dumping a shovel full of soil onto a screening table and sifting through it.

Before you all jump on my ideas, remember on Mars where there is at list a little bit of atmosphere, I’m still not convinced you would need an Apollo style, all over pressure suit.

A lot of the “clumsiness” of a pressurised suit come from bending your fingers against pressurised gloves.

I would feel a hell of a lot safer in a “skin” suit, which I envisage as a bit like a wet suit, with a pressure collar to attach your helmet to.

That way a stray rock chip doesn’t lose your whole air supply.

The same principle of “keep it simple” could apply to a rover, make it pedal powered.

In on third gravity you could cover a lot of ground and not worry about battery life or motors burning out and leaving you stranded way too far to walk back to base.

Call me crazy but I’d do it in a heartbeat!

Considering the cost of a single manned Mars mission, literally hundreds of Spirit / Opportunity – like missions could take place at hundreds of different locations across Mars. Even if the rovers traveled slowly due to communication delays, within three years, hundreds of different locations would be sampled. Using some ingenuity, those samples could be hopped to a central location, combined, and then sent back to Earth. This would be science return which a manned mission couldn’t come close to.

HOWEVER, robots cannot achieve what should be our highest priority for space – namely, the surival of the human species. I personally think that we should press the pause button for manned science missions, first achieve a small, off-Earth, self-sustaining colony. After that has been acheived, then yes, knock yourself out with however much science you wish to do.

Exactly how much is the survival of the human species worth? All science, all history, all descendents, our entire future, everything is lost if the human species does not survive. First things first!

Alex,

A very interesting and relevant thought, here. It also suggests that a sea change is coming in the robot vs. human debate: When the time comes that robots can fix broken machines, humans will have the freedom to stay away, or else to do what they are really good at. As explorers and scientists rather than mechanics and janitors.

@Michael Simmons

“We won’t be going any where until advanced tele-presence robots can be made. Ones with dexterous hands. Perhaps not quite advanced as the ones in the movie “surrogates”.[…]They would be controlled by humans in orbit would would then relocate to the surface it was completed.”

So – you bring humans to Mars, just to leave them in orbit, exposed to radiation (as opposed to being in a shelter on Mars)? To spend vast sums of money developing robots, to do the job these humans could easily do?

@Troy

“it seems that we should be able to build a robot that has the mobility and collecting abilities of a human but weighs less than the human and its support system.”

What? You’re describing ~star trek’s Data – for a machine to have the collecting abilities of a human, it has to have a comparable MIND and body. You actually think “we should be able to build” it?

We’re FAR closer to building a crewed (by humans) interplanetary ship than building such a robot:

We don’t even know if building such a robot’s mind is possible; if it is, we’re nowhere close to building one; if it is, it’s VASTLY cheaper (in both money and time) to develop a crewed interplanetary ship than to try and develop such an AI.

Something to keep in mind about having actual humans explore other worlds: Yes, Apollo did grab the public imagination at the time, but after Apollo 11 the interest began to drop off, as much as that may seem incredible to us now.

Well, circa 1970, people were still being led to believe that Apollo type missions would become routine as we worked our way up to permanently manned lunar bases and eventually colonies there. Plus we would shortly begin sending humans off to Mars and maybe even Jupiter, so going just 240,000 miles to a seemingly dead world full of gray rocks just was not going to sustain interest.

So how long do you think the masses will remain excited about human expeditions to Mars, especially since they may take over a year or more just to reach the Red Planet. And unless something radical happens, I am willing to bet that the really big space missions will still have to be funded by governments, and that has major hurdles of its own, including the fickleness of politicians and their purse strings.

Most of the people who frequent Centauri Dreams would likely follow just about every step of such missions, but imagine the reaction of a public with far less education and enthusiasm for space. Ever watch the goings on aboard the ISS from NASA Television? Star Trek adventuring it is not – not that this is the fault of the astronauts, who are up there trying to conduct research and keep the station running smoothly. During the long cruise to Mars, I expect things to be fairly similar for the astronauts on that mission too.

I want us to go to other worlds to learn about them, not to plant a flag and leave some footprints. Humans may still be more efficient exploring machines for now, but with continually improving robotics and AI, along with the development of small and portable laboratories for examining minerals and organics, having people do this work may become as redundant as when Wernher von Braun imagined manned lunar expeditions in the 1950s. He envisioned dozens of humans onboard his spaceships, filling roles that were later replaced by machines. This is one reason why there were only three astronauts on Apollo.

I remember an article in Omni magazine in the 1980s which envisioned sending dolphins to Europa to explore that alien moon’s subsurface liquid water ocean for us! Talk about exciting as we dropped dolphins in special protective suits with sensors and cameras into that distant ocean to learn if Europa has its own swimming creatures!

The reality: Besides the high cost and expense and groups like PETA going nuts over the idea of sending cetaceans on 400 million mile journeys across deep space to hazardous moons (and having to bring them back we presume), by the time we can send a mission to explore Europa’s ocean, we will likely have developed machines that can function and swim like fish (they are working on these very things at MIT), but at a fraction of the cost and capable of doing so much more.

And when it comes to interstellar missions, we will need advanced AI whether the starship has humans onboard or not. Even if the AI is not or cannot be “sentinent/aware”, it will still need to be highly sophisticated to ensure that such missions lasting decades or more reach their destinations.

Many of the problems facing a marsmission have a relatively simple solution if you make the human abilities and weeknesses the starting point for the design concept . What this means is to define the REAL minimum demands for human funktioning and health in space , as oposed to other designtraditions , perhabs originating in the aircraft industry or god knows where . A good example is the endless wasted efforts to make astronauts capable of surviving years of zero-G conditions , while any kind of simple common sense will tell you that two identical spinning habitat-modules connected by a 100m cable will solve the problem . Ofcourse this solution will have negative side effects , create new tecnical problems such as demanding a new kind og gyroscopes for stabilyzing the central hub-unit , but none of theese are more than variations on existing tecnology .

Its probably a lot more funn to be weightless ….

Interstellar Bill needs a history lesson. It was liberals (JFK, LBJ) who tried to give us both Apollo and the Great Society (which was not “welfare programs” but an attempt to eliminate poverty through education and jobs). It was Republicans (Nixon/Ford) who cut the budget for space exploration and decided that handing out welfare checks was cheaper than creating a society that everyone could fully participate in. I agree that we are still paying the price for both of those latter decisions. But let’s be honest about who was responsible for them.

NS it was Ted Kennedy and Ralph Abernathy, guests at the Apollo launch bemoaning the wasteful space spending that could do SO much more here on Earth as if the $ were launched into space, but I digress. Point being that orders of magnitude more working families earnings have been confiscated by the US government and spent on “social programs” than on Apollo. We and the recipients are NOT better off as a result.

Interstellar Bill and NS, be careful. In a democracy, leaders of the left and right are prisoners of their demographic appeal, not the other way around. That world is also one of generating slogans and arguments that sound much better than their analytical value. Thus the most important lesson to learn here is that politics is a great way for intelligent people to waste their talents. Rather than complaining about what can’t be changed, best refocus on what can be.

Let me rephrase that. Let’s help give those poor politicians a chance to leave a legacy.

Note that “wired” magazine has now picked up the story ( apparently they follow CD) . Paul always does such a good job fleshing this stuff out.

As usual the comments here are also a cut above most blog sites, with both ideas and a lightness that is fun to read.

Mars beckons folks. we can go there, and sit in our vessels and send out automated construction platforms to dig and assemble and even refine water and ores. When they break down or need a “hand” we can put on our suits and go out there and fix the problem. We can also analyze samples right there in compact laboratory devices.

One thing that is overlooked is the need for compact analytical tools -something groups like that run by Larry DeLucas ( former shuttle astronaut ) create. been to his shop and labs. it is a wonderland!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_J._DeLucas

Glad to people finally standing up and cheerleading for humans in space again- the only way you can build a robot that can accomplish what a human can do is if you can build a robot that can replace a human, and right now (and maybe never?) we can’t.

One possibility that could could reduce the cost of bringing astronauts back might be to plan for multi-year stays; after all, most Mars missions these days envisage about 18 months on the surface- very little more would be required for 5, 10 or 20 years on the surface, while the space infrastructure improves about the kinda-sorta colonists. Compare to Clarke’s Discovery mission plan in 2001, where the Jupiter astronauts stay in hibernation while Discovery II is built.

@Interstellar Bill- coulda, shoulda, woulda. We are where we are, for good or for bad; let’s plan from now, not 1972.

I’m reluctant to wade into this because I find myself in sympathy with most of what has been expressed, but I was able to observe fairly attentively the political climate post-Apollo 11 and from my own unhappy study of politics I think I can offer some thoughts:

1) We’re still riding Moore’s Law (and for at least a human generation or two longer) and given that we don’t know what is at the end of it, I think it wiser to let that unfold before rushing into getting humans into space again. Much wiser. Apollo was a trip, no doubt about it, but it has messed up our thinking. It’s history, really and truly. Let go of the romantic past. It’s long past time to consider new ideas and approaches. Eventually getting humans (or human-robot hybrids) into space will make sense, but right now it raises political problems that will make the earth-bound costs, i.e. the infrastructure to make the programs even possible, prohibitive. The scientific (megabytes/second?) ROI on robot entities is good and will only get better.

2) Most people did not understand or appreciate the Apollo program in its glory days, but now with the welfare-entitlement-dependency state growing daily and far in excess what it was in the 60s, any attempt to revive something like Apollo will lead to a PR disaster. It will be like trying to hook up with an old girlfriend. Who’s married. Don’t go there. Recall Bush’s attempt to get a Mars Program going or Newt Gingrich’s more recent call for a moon base? Both the Right and Left attacked it mercilessly. Relatively (note the word) inexpensive interplanetary probe missions can still get through Congress, (particularly if you name a probe to Uranus after a prominent congress creature) but that’s it. Not to put it too insensitively but far more of our fellow citizens are concerned with getting a recharge on their EBT card than watching some dude hit a golfball into a Martian sand trap.

So given the political, social, and economic realities here are my recommendations:

First, forget about manned space flight — with the notable exception of private endeavors. On the whole our fellow citizens are more tolerant of the antics (their perception, not mine) of rich folk doing a space number than they are of the government spending a dime on manned missions. Nobody got upset, for example, about Cameron going down into the Marianas Trench. (I rather he did that than make movies.) Try that with a massive government program to do the same and watch the excitement. I don’t like it any more than you do but that is the political reality we live in.

Second, forget about the government and its all-you-can-spend credit card. We live in the brokest nation in history. Space exploration will be the first to go once the economic catastrophe ensues when interest charges alone eviscerate our finances. Space advocates are like the first mammals scurrying under the feet of the government dinosaurs towering overhead. Eventually they will fall. Let’s not be underneath. That’s absolutely necessary. I don’t know if it will be sufficient.

Third, investment in technology for the improvement to near-space access is paramount. I know I’m something of a bore on this, but there is good news. As space launching becomes more of a private enterprise thing, a market will emerge and we will see the whole business become more economical. That will spur research and who knows what ideas will come from it. That’s as hopeful as I can get. When I’m down I find myself thinking that by the end of the century everyone’s idea of a far-out space probe will be throwing rocks at the moon. I think (hope) humanity can do better.

Johnq, if you really have to go down the road that examines social and political barriers to space exploration, why use a model that assumes a fixed landscape? Isn’t it obvious that key events can transform this such as the JFK assignation and Apollo?

Think of two recent transformational events. Think how the USA’s military expenditure looked as if it was locked into long term decline until it was transformed by the events of September 11 (just prior to that I was taking bets with friends that America were about to return to isolationist policies). Also think of how the anthropogenic global warming debate lead to the redirection of hundreds of billions of dollars in first world expenditure.

Now imagine a Tunguska like event near a city, or causing a deadly tsunami, might change this landscape to change overnight. Thinking of the second example, this might not even need to happen, there just needs to be such a condenses on it that even politicians can’t ignore space as being a field that is only of interest to a closeted few.

I marvel about how many otherwise perfectly reasonable people can turn a momentary, somewhat worse than average economic downturn into a prophecy of doom for the human race, or at least the space program. Guys, get real! These things come and go in a matter of years. In this forum, we should be looking at a bigger picture, and a bit more long-term.

And we should not be discussing whether it is pampering the poor or greed of the rich that are to blame, neither is relevant here. We are speaking about science, which is about equally distant from welfare as it is from obscene wealth. Yes, politics is everywhere, but it is best left to the politicians.

Ignoring my own admonishment, but I can’t resist:

@Bill:

Should that be:

Thank you for the comments. I didn’t want to sound like Donny Downer but I felt the question of resuming large-scale manned splace flight needed to be put into a broader context than just the science and engineering of the matter. And the context for the near-term is not promising.

>Eniac: Yes, politics is everywhere, but it is best left to the politicians.

Unfortunately, politics is too important to be left to the politicians. We have to be aware of the political realities though we don’t have to grovel before them. The fact of the matter is that a giga-buck Apollo II-type program is not going to happen. Given that, what can we as space enthusiasts, whatever our level of wealth or attainment do to keep the business going? It is incredibly important and I regret if I came across at any point as consoling indifference or despair.

>Guys, get real! These things come and go in a matter of years.

Regrettably, the economic, social, and political crisis now and emerging is a whole different beast than the standard-issue recession which a few adjustments or personnel changes will correct. The trillions and trillions of debt is an effect not the cause of the monumental problems we face. Paraphrasing what Trotsky said about war: you may not be interested in economics/politics but they are most emphatically interested in you. Awareness of the full context in which these decisions (i.e. regarding manned space flight) will be made is of vital importance. Not everyone will agree, but I won’t retreat from what I wrote.

>Rob Henry: Johnq, if you really have to go down the road that examines social and political barriers to space exploration, why use a model that assumes a fixed landscape?

Presuming a “fixed landscape” was the last thing I wanted to do. I was presuming massive changes ahead, all manner of upheavels, yes. Unfortunately most of the consequences look rather grim. All I was trying to do was given the nature, extent and degree, of what we will be facing this decade and beyond, assuming worst possible case in other words, what might be the best strategies to keep space exploration going? I think the recommendations I made are sound, but they are hardly the last word. I would be thrilled if others added to them. Of course, an asteroid could head this way and that will really revitalize interest in manned space flight, which may be the type of scenario you are thinking of, but I don’t feel a need to speculate on it. Such a thing could happen, of course, but is that how we want to direct our thinking?

In any event, I actually thought my recommendations with both positive and on topic. If anyone thought otherwise, I regret not being sufficiently clear.

Johnq:Regrettably, the economic, social, and political crisis now and emerging is a whole different beast than the standard-issue recession which a few adjustments or personnel changes will correct. The trillions and trillions of debt is an effect not the cause of the monumental problems we face. I think you are plain wrong about that. We have had bigger problems in the past than we are facing now, and chances are that we will get past these ones in due time, not too long from now.

>Eniac: We have had bigger problems in the past than we are facing now . . .

Nothing would please me more than if you were correct.

johnq said on April 13, 2012 at 16:07:

“Paraphrasing what Trotsky said about war: you may not be interested in economics/politics but they are most emphatically interested in you.”

Well worth repeating, along with just about everything else you said in that post of yours, John.

The only vacuum that exists is in space, and even that isn’t a perfect one.