By Michael Michaud

The following post is a distinct change of pace for Centauri Dreams, a work of fiction that gets at questions at the heart of SETI. We’ve considered many ideas about interstellar probes that humans may one day launch toward nearby stars. But the reverse could occur: A more advanced technological civilization could send a probe in our direction, particularly after detecting signs of life or technology on a rapidly developing Earth.

This idea is a challenge to the dominant scientific paradigm of contact — our detection of radio signals from a remote society. The short story below presents one of many possible scenarios. In this case, the probe is an intelligent machine. It lacks the omniscience so often assumed in films and television programs; this form of intelligence, like ours, can misunderstand evidence and is capable of making mistakes. This story avoids the two stereotyped film and television versions of contact: being saved by altruistic aliens, or being attacked by vicious conquerors.

The story is not complete. Its author invites you to write your own ending. What should the discoverers do? How would governments react? What roles would scientists and the media play? The author hopes some of you will rise to the challenge.

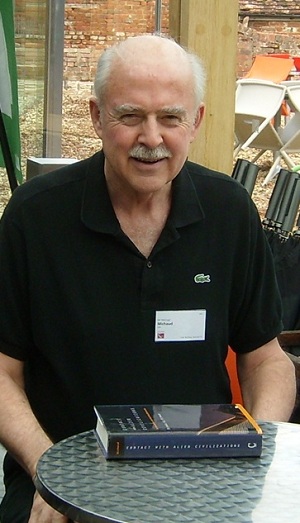

Michael Michaud is the author of Contact with Alien Civilizations: Our Hopes and Fears about Encountering Extraterrestrials (Springer, 2007), along with numerous other works including many on space exploration. Michael was a U.S. Foreign Service Officer for 32 years, serving as Counselor for Science, Technology and Environment at the U.S. embassies in Paris and Tokyo, and Director of the State Department’s Office of Advanced Technology. He has also been chairman of working groups at the International Academy of Astronautics on SETI issues. Here he takes us into a scenario that could happen one day. If it did, how would we respond?

Alan guided Esperanza with sensitive fingers, feeling the shifting pressures of the ocean on her keel, watching the stress and easing of her sails. Aiming the big ketch’s bow at Catalina Island, he evened out the yacht’s motion to give his partner the stable platform she needed.

Robin hunched over her instruments. The tall, lanky woman had folded herself into the science cockpit that she and Alan had designed together. She was watching for evidence that warmer Mexican waters were penetrating northward into the cold California current.

“I see some signs,” she told him, “but they are subtle, ambiguous. This isn’t strong enough evidence to convince other scientists.”

Alan suddenly pointed off the starboard bow. “What’s that?”

Robin’s keen blue eyes focused on a metallic object rocking in the waves a quarter mile away. “It’s an automated submersible, part of the ARGO system. There are hundreds of them, all over the world ocean. They sample the chemistry and measure the currents, as far down as three thousand feet.”

“What is it doing on the surface?”

“They’re programmed to come up every ten days to report their findings by satellite.”

“A mind in the waters,” commented Alan.

“Yeah,” said Robin, “but made of silicon.”

They watched the robot doing its job. Its message sent, the machine sank out of sight.

Alan mused aloud. “If you wanted to hide a clandestine undersea vehicle, you would make it look just like that.”

Robin switched off her instruments. “Enough with ocean research for today. I’ve hit the saturation point. Is there something else we can do, just for the hell of it?”

“Have you ever watched a meteor shower?”

“I tried once on Long Island. There was too much urban glow.”

“Tonight we’ll get one of the best of the year. We could anchor off Catalina to watch it.”

“There’s a lot of light on this side of the island, like those camps for religious groups.”

“Then,” said Alan, “we’ll go over to the Dark Side.” Robin groaned, theatrically.

Alan needed her help with the sails as they rounded Catalina’s west end. He and Robin managed the lines together, working as a well-practiced team.

Robin trusted her captain. Alan had reached out when her scientific career stalled, giving her a place aboard as crew for his charter voyages. Stocky but trim, he was warily alert to the ocean’s moods.

Suddenly, Esperanza faced a vast, empty Pacific. Alan and Robin glanced at each other, wordlessly. They had talked of greater voyages, of lonely atolls and distant reefs, where the test and the joy lay in mutual reliance.

They found a deserted cove, dropping their anchor in deep water. After dinner, they lay back on the deck to watch the sky, as dark as it was before electricity.

Far above them, Earth’s atmosphere encountered a swarm of rocks and ice. White streaks emerged from a focal point in the sky. Meteors flashed their brief lives.

“It’s like being the target in a shooting gallery,” said Alan. “I’m glad they burn up before they hit the ground.”

Robin pointed upward. “What about that one? It’s not moving.”

Alan focused on the point of light. It had no tail, no streak of incandescent matter. “Is it my imagination,” he asked, “or is that thing getting brighter?”

“You’re right. It’s coming straight at us!”

Alan tried to be reassuring. “The odds of a meteorite hitting us are infinitesimal.”

Robin’s eyes widened as their fiery visitor grew in size. “We need to take cover!” She dove into the main cockpit, Alan tumbling in after her.

The ocean erupted a mile away, a tower of water bursting upward into the night sky. The sound quickly followed — a crackling whoosh, then a boom that shook the boat.

“Hold on!” Alan shouted. Spray rained down on the huddled sailors. Violent waves rocked Esperanza, straining her anchor chain.

Robin raised her head, watching the restless ocean subside. “That was close!”

“The meteorite may have survived,” said Alan. “Let’s look for it.”

“How?”

“It’ll stay hot for a while. We may be able to spot it through Rover’s infrared sensor.”

They uncovered their remotely operated vehicle, the gadget-loaded undersea craft that extended their reach deep into the ocean. Rover was more than a tool to Alan and Robin. With its own eyes and its own means of locomotion, the ROV had a kind of personhood. It was the closest thing they had to a child of their own.

Alan attached Rover to the yacht’s lifting boom, lowering the machine into the ocean. Robin, at the controls, guided the submersible through the darkness.

They watched the screen intently as Rover neared the point of impact. Nothing but inky blackness.

“Let’s set up a search pattern,” said Alan. “Back and forth, close to the bottom.”

For long minutes, they saw only the dark.

“There!” said Robin, pointing to the edge of the screen. “I see a faint glow on the ocean floor. I’ll send Rover in for a closer look.”

Alan discerned a blurry image, an unearthly shine. “Can’t see any detail.”

“I’m switching to visual,” said Robin. “I’ll turn on the lights.”

She snapped on Rover’s powerful mercury gas lamps. The sudden brightness overwhelmed their vision.

As their eyes adjusted, they made out a dark lump on the ocean floor, lit from within. “It looks like a molten chocolate dessert,” said Alan.

“You would think of that. Hey, do I see something moving?”

“The meteorite is changing shape. They’re not supposed to do that.”

They watched the dark material sliding off the mysterious object, revealing a brighter surface underneath. Robin’s jaw dropped. “It’s shedding!”

“That,” said Alan, “is no meteorite.”

Forgetting to breathe, they watched a glowing crystalline object emerge from the blackness. Robin gasped. “It’s beautiful!”

“Are we seeing internal structure?” asked Alan. “There seem to be patterns, in three dimensions.”

“It keeps changing. It’s like watching a kaleidoscope.”

“Let’s turn on all the detectors. Everything you use for research.”

The hydrophone picked up a soft beeping sound. Alan and Robin listened intently.

“Maybe it’s a tracking signal,” said Alan, “so the people who launched this thing can find it.”

“No, wait. It’s more complex, like a message.”

“As if it were trying to communicate with Rover.”

“One machine to another,” said Robin. “But Rover isn’t smart enough to respond.”

“We are. Let’s signal back.” Alan sent low-power pulses from Esperanza’s directional sonar.

The glowing object silently rose from the seabed, shedding the last of its dark covering.

“It’s oval in shape,” said Alan. “Like a streamlined football.”

“I’ll tell Rover to follow it.”

“Where is it going?”

Robin studied the plot that showed Rover’s location. “Toward us.”

They watched as the visitor approached Esperanza’s steel hull. The glowing machine stopped twenty feet off their bow. Robin maneuvered Rover to a respectful distance, while Alan preserved the scene on video disk.

“I’m receiving a burst of signals,” Robin reported.

“It’s talking to us,” said Alan.

“I’ll record the message.”

“Can you make sense of it?”

“I’ll try the program I use to extract patterns from dolphin signals.”

Alan waited a decent interval, worrying that their visitor would leave. “Any luck?”

“I can’t make out a message,” said Robin. “It’s more like radio noise.”

“Maybe it’s not a language we can understand.”

Robin threw up her hands. “We have to do something, before it gives up on us.”

“Send it the most complicated digital files you have. Even if it doesn’t understand, it will recognize our messages as complex.”

“I have a bunch of oceanographic papers in the computer. I’ll convert them.”

“I’ll try to keep it entertained by turning the lights on and off.”

He watched as the ovoid machine disappeared into the darkness, then returned into the light. Its subtle color changes made his signals seem as mindless as airport beacons.

He introduced patterns, short and long. Would the machine understand an SOS?

Robin finished converting her files, full of words and data in digital form. “Who would find this interesting,” she asked, “except another oceanographer?”

“I love reading your papers,” said Alan.

“Yeah, yeah. When you want to put yourself to sleep.”

“Try sending one.”

They waited in frozen silence. Another burst of signals came from the visitor.

“It worked!” said Alan. “Keep transmitting.”

Robin continued sending her papers. The glowing object beeped politely after each one.

“Where did this thing come from?” she asked. “Could it be some exotic military technology?”

“I would be surprised if any country is this far advanced.”

She stared at him, waiting for his next sentence. He said nothing.

They ran out of files as the dawn began lighting the sky outside the boat. Their visitor remained silent.

“Maybe it’s analyzing,” Robin said hopefully, “digesting our messages.”

“Why do I get the feeling,” asked Alan, “that we’re not telling it anything it doesn’t already know?”

“We can’t keep using the word it,” said Robin. “That thing has a mind. It deserves a name.”

“How about Art, short for artifact?”

Robin shook her head. “Ugly. We’ll call it Artemisia.”

“You just gave it a female gender.”

Robin tilted her nose slightly upward. “It is a more advanced form of life.”

Suddenly, Artemisia began to move.

“Dammit!” cried Robin. “She’s turning away from us. Where is she going?”

Their hydrophone picked up new sounds, the chugging of an engine, the whine of a propeller. “We have company,” said Alan. “Let’s go topside to see who it is.”

He scanned the horizon through his binoculars. There, approaching from the north, was an aged trawler belching smoke.

Alan studied the small, seaworn ship, her sides streaked with rust. “She’s equipped with a crane, like a salvage vessel.”

Robin checked her screen. “Artemisia is sinking back toward the sea floor, disappearing into the dark. Maybe she doesn’t like the noise.”

“Send Rover after her,” said Alan. “I’ll watch the trawler.”

Focusing on the ship’s wheelhouse, he saw a bearded man at the helm. “I bet this guy is a salvager looking for a wreck. There’s a shotgun hanging on a rack behind him. Do we still have a rifle on board?”

“I’ll get it,” said Robin.

“Keep it out of sight until we know what’s going on.”

The trawler slowed to a stop thirty yards away. Alan heard the engine grind into neutral.

The bearded man stepped out of his wheelhouse, speaking through a loud hailer. “I’m looking for a meteorite that hit near here. I tracked it from the mainland. Did you see where it came down?”

“Are you a scientist?” asked Alan.

“Naw, just a collector. I sell them on the Internet.”

“We saw a bright meteor trail,” said Alan. “Something hit the water, but it was farther offshore. Maybe two or three miles.”

Robin, standing in the companionway, watched her partner’s face as the trawler chugged away. “Not like you to shade the truth.”

“He would sell Artemisia to the highest bidder.”

Two miles out, the trawler began tracking back and forth, searching the sea bottom with a towed array of sensors. Alan worried aloud. “What if Artemisia sends signals to him too?”

Robin checked her instruments. “She’s silent, as if she fears the trawler.”

“You’re giving her emotions.”

“Any intelligent being may be wary of strange men.”

“Thanks for implying that I’m not strange.”

“So what do we do? Wait until meteor man is gone?”

Alan studied the trawler’s movements. “His search pattern is bringing him closer to shore. Toward us, as if he suspects our story. We should get under way to draw him off.”

“And hope that he won’t find Artemisia?”

“Let’s ping her with sonar, then begin moving away slowly. Maybe she’ll get the hint.”

Robin sent the briefest ping their sonar could produce. Rover’s screen showed a glow in the dark. “She’s still responding to us.”

Alan nodded. “I’ll start the engine.”

“She doesn’t like engine noise.”

“Ah, yes,” he said. “Females are more sensitive.”

Alan hoisted minimum sails, then raised Esperanza’s anchor. The yacht slowly drifted south, moved as much by the current as by the wind.

“I have to tell Rover to catch up with us,” said Robin.

“I’m sailing as slow as I can,” Alan replied.

Robin watched the video image from the ROV. “Artemisia is rising again. She’s following us.”

Alan deployed the lifting boom to bring Rover back to the yacht’s deck. “Will Artemisia want to come on board too? She may be too heavy.”

“She’s maintaining the same distance.”

Robin set up a program to transmit underwater signals at regular intervals, like a beacon. “I hope this is enough.”

Rounding the east end of Catalina, Alan steered for the California coast. Robin held her breath, hoping that Artemisia too would change course. That mysterious being followed Esperanza like an intelligent dog.

Robin heard Alan’s expelled breath. “You were worried too,” she said.

“Artemisia is a lot more interesting than any machine I ever knew.”

Alan pointed off their beam. “Dolphins, leaping out of the water for the sheer fun of it.”

“I can hear them through the hydrophones,” said Robin. She listened intently. “I’m picking up something new. Artemisia is imitating the dolphins’ squeaks.”

“She’s communicating with them too?”

“She’s turning away from us! She’s following the dolphins!”

“We can’t keep up with dolphins under sail.” Alan reached for the ignition. “The engine will help a little.”

“Yes, yes!” shouted Robin. “I’ll send her every kind of signal I can think of.”

Robin filled the near sea with messages, hoping desperately for a response. The squeaks receded into the ocean’s background noise, now corrupted by Esperanza’s diesel. The dolphins – and Artemisia – were gone.

Esperanza rocked in the waves, until Alan and Robin accepted their loss.

Alan grunted. “It’s humiliating to think that we’re less interesting than dolphins.”

“At least we recorded her signals. Maybe someone can figure out what they mean.”

“We got video, but the quality is not very good.”

“Dammit!” Robin cried. “That was once in a lifetime.”

“Alan spoke gravely. “Maybe once in a millennium.”

“What…” She pointed to the sky. “You think Artemisia came from out there?”

“I know what most scientists would think of that theory. But I can’t come up with a better one.”

Alan and Robin sailed home in sullen silence. They brought Esperanza into her slip, making her fast with docking lines.

“We should clean up the boat,” said Alan. “Shut down all the systems.”

“Not tonight,” said Robin. “I’m too depressed.”

Alan lay in his bunk, trying to read. Nothing held his interest. Nothing matched Artemisia.

What could she have been? An artificial brain, with an impervious shell and an invisible propulsion system?

Some scientists had speculated that humans would be succeeded by intelligent machines. Would they be just sophisticated robots, or could they choose what they would do and where they would go?

Machines could tolerate hardship and boredom far better than a biological being. Would such a sapient entity have feelings?

If Artemisia had stayed longer, he and Robin might have been able to tell. Now she was gone, because they had not been clever enough to hold her interest.

Alan hung a transmitting hydrophone off Esperanza’s stern. Connecting his multi-disk player, he began transmitting music into the deep. He started with Bach’s greatest fugue.

A silly thing to do. Like leaving a porch light on in the hope that your angry lover will return, forgiving everything.

Alan arose early the next morning, letting Robin sleep.

He began washing salt off the boat. As he wiped down the stern rail, he noticed an odd glow in the water. He leaned overboard, staring into the murky darkness.

A smile spread slowly across his sun-damaged face. “Well,” he said, “hello there.”

Robin hugged him as if he had saved her life. Alan shrugged modestly. “Maybe we are more interesting than dolphins.”

“We need to show her that we want to exchange information, to converse.”

“Converse? How?”

“I don’t know yet. I’m running her signals through the best analytical programs I can find. Her language is not like anything I’ve ever seen.”

“Maybe she found dolphin language more recognizable.”

“That could be it!” said Robin. “She may have thought that intelligent life exists only in the sea.”

Alan extended their thought experiment. “She, or whoever sent her, may not have known of humans.”

“How could they miss us? We’re noisy as hell, sending out radio, television, and radar signals.”

“They might have been searching for other forms of life, or other evidence of intelligence.”

“Why would she stick around when we have nothing to offer but scientific junk mail?”

Alan scratched his unshaven chin. “We may be the surprise.”

“I’m running out of things to send her.”

Alan pondered. “You receive television through your computer, right?”

“Everyone does, except you.”

Alan ignored the dig. “How about sending her the news?”

Robin brightened. “It’ll take me a while to program that.”

“What am I going to do to keep her interested in the meantime?”

“Well,” said Robin, “you could sing to her.”

Alan donned his wet suit, slipping into the water beside Artemisia. Hesitantly, he laid his hand on her translucent surface, half expecting a shock. He felt nothing but crystalline hardness.

Her internal glow seemed brighter. Is she responding to me?

Alan sang every song he could remember, making up phrases where he had forgotten the words. How awful this must sound, with the distortion of the watery medium and his own limitations as a singer.

He remembered Robin’s sarcasm. Jailers could use his singing voice on prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. Surely they would confess.

Artemisia beeped. More slowly this time, as if she were adjusting to his inferior intelligence.

He was feeling the first numbness of hypothermia when an object appeared in front of his face mask — the small board that he and Robin used to write notes while they were diving. Robin’s message was brief: “I just started sending her the news.”

Alan was slow to rise to the surface. “Can’t talk,” he croaked. He had given Artemisia everything he had.

Robin helped him to stand. She threw an arm around his waist, bracing him against a fall.

“Let’s watch the news,” she said, “on a real television set.”

The images on Esperanza’s screen seemed even uglier than usual, the commentary even more inane. “This may convince her,” said Robin, “that we really are stupid.”

Alan pointed to the screen. “Navy ships are conducting a search operation off the back side of Catalina.”

Robin studied the steep island slope in the background. “That’s where we were.”

“They’re using a submersible. They’re looking for Artemisia.”

“If Meteor Man talked, the Navy will come to see us. They’ll see the glow. Where can we hide her?

“Maybe we can put something over her, to disguise her.” He paused. “If this is a serious investigation, they may seize your computer.”

“All my work is on that machine!”

“Can you transfer your files?”

“I’ll put them on disks, then overwrite the data. I hope that’s enough.”

Alan grabbed their underwater video camera. “I’ll take close-ups, just in case we lose her.”

The Navy telephoned the next morning, inviting themselves aboard Esperanza at ten.

“Time to hide our visitor,” said Alan. He donned his SCUBA gear, picked up a tarpaulin, and slid quietly into the water.

He hovered over Artemisia’s glowing bulk. “I need to cover you for a few hours,” he told her. He must sound as idiotic as barbarians sounded to the ancient Greeks. Ba ba ba.

As gently as possible, he spread the tarp over Artemisia. He backed off a few feet to watch her reaction.

A gleam penetrated the tarpaulin, turning it translucent. The fabric began to disintegrate, sheets of material falling away. Soon there was nothing left.

I should have known, thought Alan. Don’t imprison intelligence.

Very cautiously, he approached Artemisia again. “I’m sorry,” he said into the water, “but I have to hide you somehow. If I don’t, they’ll take you away.”

He extended his hand toward her, fearing that his flesh would be vaporized. No heat.

He laid both hands on Artemisia’s top. Using his swim fins for leverage, he gently pushed her down. She sank to the bottom without protest.

“Wait here,” he said aloud. “I’ll be back.”

Is it just darker down here, or has her glow diminished?

Robin paced nervously on the pier, wondering what the Navy would do. She imagined armed men brushing her and Alan aside, stripping the yacht, carrying away everything that mattered. They would haul Artemisia out of the bay, dumping her on to a barge. “National security,” they would say.

Too much Hollywood. The Navy had sent only two people, a man and a woman in crisp dress uniforms.

Robin spoke quietly to Alan as the Navy people approached along the pier. “One of us has to lie.”

“And you just nominated me.”

“What if they want to search the boat?”

“We have to let them. If we don’t, they’ll be suspicious.”

“I didn’t have time to clean up my cabin.” Robin studied the neatly dressed female officer. Not a hair out of place.

Captain Babb and Lieutenant MacDonald were attractive officers with excellent posture and keen, penetrating eyes. The Navy had sent its best.

“You must have seen the meteor,” said the firm-jawed Babb.

“Yes,” Alan replied, “we did.” Be responsive, with minimal information.

“It shook us up,” Robin added.

Lieutenant MacDonald focused her bright green eyes on Robin. “You do oceanographic work. Did you search for the object?”

“We looked, but we didn’t find a meteorite.”

Alan intervened. “You might want to ask the man in the trawler. He was equipped to pick up something heavy from the bottom.”

“We did,” said Babb. “He didn’t find it either.”

“I can understand why scientists would be interested in a meteorite,” said Robin, “but why the Navy?”

“It may not have been a meteorite. It may have been a satellite re-entering the atmosphere.”

“One of ours?” asked Alan.

“Can’t say.”

Lieutenant MacDonald smiled at Alan, with fatal charm. “Mind if we look around?”

The Navy people went through every compartment, opening doors and hatches. Robin stayed with them, trying to be cordial.

Alan remained on deck, nervously glancing over Esperanza’s stern. No sign of Artemisia.

As the Navy officers came up from below, he spoke toward the bow. “Everything okay?”

Captain Babb stared into Alan’s eyes. “If you learn anything about this object, can we count on you to tell us?”

“Sure,” Alan responded uncomfortably.

Lieutenant MacDonald smiled, enchantingly. “We’ll be in touch.”

Alan and Robin watched with fixed smiles until the Navy people were out of sight. Alan leaned against a stay, expelling a contained breath. “I hate lying to people.”

“I know,” said Robin, “and so do they.”

Alan returned to the water to raise Artemisia from her hiding place. Robin logged on to her computer to search relevant blogs.

After an hour, she found what she did not want to find. The most credible of the UFO sites reported a rumor that the object striking the sea had not been a meteorite, but some sort of alien craft.

Alan watched over her shoulder as Robin checked other blogs. “This story may spread,” she said.

Alan tried to be reassuring. “It won’t have much credibility.”

“Should we go to the media, tell the real story ourselves?”

“They won’t believe us, unless they see Artemesia with their own eyes.”

“We could give them the video.”

“A mysterious fuzzy light on a dark background? The media have been there before.”

“We can’t keep this to ourselves forever. We don’t have the resources to deal with Artemisia.”

Alan nodded. “At some point, we have to inform the right people.”

“And who might they be?”

“Would scientists do the right thing if they knew?”

Robin spoke sharply. “I wouldn’t count on that. Some of them think they know what’s best for the rest of us.”

Alan tried to step back from his feelings. “We don’t own Artemisia.”

“No one should.”

They stared at the screen as if that would help. The computer offered no wisdom.

“What should we do?” asked Robin. “What should we do?”

——-

Now, dear reader, it’s your turn to suggest the next events in this story. How should it end? What should the discoverers do? Feel free to write an ending of 1000 words or less.

Copyright Michael A.G. Michaud 2007

I posted the link to this “challenge” at myouterspace.com, at the Creatia (writers’) discussion group, whose “governor” is Alan Dean Foster.

:-)

Of course the solution was obvious. Within less than hour, we could travel to international waters where we could begin uploading everything we had learned about Artemisia. Also, Artemisia had quickly learned how to communicate through our system and was now expressing herself directly to the world. And that’s when what we know as human history ended.

Hi Paul and Michael,

Nice change of pace ,thank you. I have wondered that perhaps we were too deep in the weeds of tech,it is important to step back and use other modalities on a issue or problem. For some reason I am reminded of a essay by Loren Eiseley which ends with a observation by Thoreau that there are some encounters with ‘Nature’ that one does not bother report to the Royal Society. First Contact no matter the form will pry off the lid on all sorts of cherished assumptions that we humans have. So my ending would be for them to have a coffee and a long think,

my personal opinion is that ‘we’ will have far less control of events that we can imagine or like. One thing is clear,looking up at the skies after Contact

will never be the same,out there, others.

Best regards,

Mark

“We have to figure out how to communicate with her.” Alan responded. “If she is able to communicate with us, we’ll have a much easier time revealing her existence to the media. If the Navy finds her before the public, they’ll have unlimited discretion over how to treat her.”

Robin appeared lost in thought and then a smile spread across her face. “We don’t need to go to the media. We can learn to communicate with Artemisia and get the media to come to us at the same time.”

Alan raised his right eyebrow, “How?”

“My roommate works for an advertising agency. She’s always talking about these viral marketing campaigns that cost nothing to produce and reach millions of people. We can create a viral ad for Artemisia.”

Alan either didn’t get it or just wasn’t convinced. “Oh, I see, we post fuzzy video of an indistinct underwater light on Youtube and wait for the help to pour in.”

“Remind me again why you’re not in sales?” quipped Robin. “Viral advertising isn’t just posting videos on Youtube. We can do this by creating an online mystery around Artemisia for people to solve. We don’t even have to raise the concept of a UFO. We can post the recordings of her communications on the website and challenge people to help Artemisia by decoding her song.”

It became clear to Alan that maybe he had been spending too much time on the ocean. He still wasn’t quite connecting all of the dots. “Who or what do we say is Artemisia and why would anyone care enough to decode her song?”

“That’s part of the mystery! We don’t have to, and probably don’t want to, specify any of that.” explained Robin. “I never would have guessed that my roommate’s incessant chatter about viral marketing would have ever come in handy.”

Alan was too tired to try to understand exactly what Robin was proposing. But his lack of any real alternative and Robin’s enthusiasm were enough to convince him that this was their best course of action. “Let’s get some rest and go meet with your roommate in the morning.”

First the characters would shield signals from emanating outside of the study area to prevent any hostility, then the characters would conduct surveillance and analysis of signals. Further operations and course of action would depend on findings.

The characters might utilize the resources of others if available to shield signals and also crowdsource analysis or rely on trusted professionals to intrepret data.

The public would be kept in the dark.

You have a good chapter 1 there. Chapter 2 is clearly when the Navy keep Alan and Robin under secret surveillance, seize Artemisia and arrest Alan and Robin for obstructing national security. Ch.3 is the interrogation of the two scientists, and their release in despair, under orders to reveal nothing to anybody. (This follows more from scriptwriting logic than a realistic portrayal of the likely confusion following such a discovery.)

Ch.4 reveals that Artemisia-2 has been discovered in Russia, Artemisia-3 in Europe, Artemisia-4 in Africa… the probes are now public knowledge. (Only the UK government believes that you can fully explore an entire planet with a single shot of a single probe…) It is established that the probes are indeed of alien origin.

Ch.5 draws in characters in a concurrent war in which American-led UN forces are battling insurgents in some rogue third-world state, in which both sides claim that the probes prove the rightness of their cause, one side holding them up as an example of the cosmic destiny of peaceful capitalist democratic development, the other holding them up as a sign from their tribal deity that the evil imperialists are about to be destroyed. (The probe that landed in that region may be seized first by one group, then by the other — some exciting action scenes in here.)

In ch.6 the mother craft in highly elliptical Earth orbit takes action to retrieve the probes which the humans foolishly thought they had possession of. (Of course there’s a mother craft!) Ch.7 therefore necessarily involves some crackpot general taking a shot at the mother craft in the belief that it is a threat to national security. The alien ship may be destroyed, but I think we’ll stay with the theme of the more advanced alien technology and allow it to slip away after issuing a stern warning to humankind, in the manner of Klaatu returning to his home planet in “The Day The Earth Stood Still”. Thus the status quo is restored, which is a good literary ending, if not quite what you’re hoping for from this script.

My suggestion above is all drafted from the point of scriptwriting logic. But I’m not sure whether I can make the story work from an astronomical point of view. Assuming that we have a high-tech alien version of Viking-1 or Titan Mare Explorer here, then either it is (as you suggested in your introduction) sent to investigate signs of industrial civilisation evolving on Earth, or it is not. If it was sent without prior knowledge of technological humanity (which the story leans towards, with Artemisia more interested in chasing dolphins than landing on the White House lawn), then its arrival at this specific time, just as the first species able to do so has started to take an interest in astronomy, is inexplicable. Why not a billion years ago, or a billion in the future? Such a coincidence is excusable in a story (without such improbable coincidences, a large fraction of literature would be wiped out!), but not as a plausible astronomical conjecture.

So Artemisia must have been sent in response to the Galactic Council being informed that an industrial civilisation has appeared on Earth, and needs to be investigated. But how far has the news of our existence travelled? Clearly, if we go by the earliest radio signals then only stars within a radius of 111 light-years or so can be in the know, and that is before we take into account the weakness of the earliest signals and the enormous dilution they experience over interstellar distances. So the Galactic Council must be well within 100 light-years in order to know anything about us — or at least an outpost of the Council, capable of observing us and passing the news on via tachyon radio (superluminal signalling).

Such an outpost would of course be most probably situated in the Solar System itself, and so you have a picture of long-lived (millions to billions of years!) probes sitting in planetary systems around the Galaxy waiting for intelligence to evolve which they can then investigate. Possible, but far-fetched. Our experience of life on Earth is that it spreads, grows, colonises new niches. Would a Galaxy permeated with high-tech life to such an extent that probes would arrive on Earth within about 300 years of the invention of the steam engine actually look as lifeless as it actually does? Or would we awake from the Stone Age to see artificial, industrial activities all around us? Would the gods of ancient mythology become, not a fairy tale from the childhood of our species, but an ever more concrete reality in our lives?

Others will disagree with me for a variety of reasons, but I find this rapid response to our appearance on the scene highly implausible in the context of our real-world astronomical situation. Good for a story, of course. But in reality? So I cannot persuade myself that Michael Michaud’s story is ever likely to happen in real life.

Of course you will invoke Clarke’s Third Law, and what can I say against that? Yet supposing a centre of alien civilisation far enough away that we haven’t spotted it yet, you need something like clairvoyance on their part in order to sense our existence, in which case they hardly need a material spaceprobe (so old-fashioned!) to add to their knowledge of us.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

Paul, you have my attention now, I just hope that you will post ‘the rest of the story’. (This is like waiting for ‘Who shot JR?’ all over again. )

Great story! Enjoyed this so much and am thinking about a conclusion. An immediate thought that came to mind in respect of the story thus far, is that Artemisia probably didn’t enter from the meteor shower’s radiant and therefore would have stood out as not being a meteorite… or very cleverly, did it? I enjoyed Alan’s and Robin’s almost immediate connection to Artemisia, a behaviour that one might expect intelligent beings to exhibit.

@Thomas M. Hermann – good one, don’t stop there!

@ Michael Michaud – I’m sure that in one scenario, dolphins come to the rescue as the navy closes in. Having recognised Artemisia as intelligent and able to communicate with them, something the dolphins had attempted patiently over the ages with human beings, dolphins en masse swarm about the visitor and take every opportunity to offload their frustration with those supposedly intelligent land dwellers lol. Conclusion – ‘goodbye and thanks for all the fish…’

Astronist beat me to the punch, although I would frame it in non-story fashion.

The framing is set so that our two protagonists are white (well at least Robin is) western educated, scientists. They use a sail boat. So they must be good people.

The US Navy is described in a threatening way – they search the boat without invitation, a clear play on the evils of unchecked authority. (In practice they had no jurisdiction to do anything).

The reader is left to answer what Alan and Robin should do, that is their morality is the one that counts. We can obviously put ourselves in their place.

Now let’s shift frames. Our protagonists are not US citizens, but are foreigners located in a nation that we find not so friendly, China, N. Korea, Iran. Perhaps they are not educated to western levels, nor is their morality quite the same. Do we still let them make the decisions for us?

Is the US navy a problem? Do they know something Alan and Robin don’t know?

Is Artemisia, described in a non-threatening way as almost a “puppy dog” machine, really so non-threatening? Perhaps it is made to be a lure? It’s task may be to seek out gullible locals to feed it the information it needs for some unknown purpose. Recall that it never provides anything of value to the humans, just takes information. What if Alan and Robin connect it to the internet, then what happens?

Why assume there is only one device, and not many? They may be all over the planet acquiring information. The question of what to do, is now dispersed across different people and organizations.

There may be a mothership[s] in orbit. Alan and Robin don’t know this. Maybe the government does. Perhaps there are indications that the probe is a danger, or at least a potential one, based on something it did while being tracked in the solar system.

So we should be careful about whose motives we ally ourselves to, particularly as we are given very little information about the device and assume it is benign without any evidence supporting this.

Reminds me a bit of The Hydrogen Wall, by Gregory Benford. Except in that story the intelligent “probe” is a message with a schematic for building an alien mind to serve as an ambassador to other civilizations.

Thomas M. Herman continuation was too good. All others are after the Lord Mayor’s Show.

For my part, I would have made the later actions of the probe duplicitous, with it perhaps later non-lethally harpooning someone, for what turns out to be a tissue sample. Anyhow, I would give it some action would seem to preclude its benevolence towards humanity from our viewpoint. Eventually we work out that it is both willing and able to help us, it is just that the requisite diplomacy is missing. We turn out to be very low on its list of priorities.

We no longer contact isolated tribes on remote islands, as past experience has proven that such a contact is devestating to their existance. And that’s difference in deveopment measured in thousands of years not in millions.

For advanced civilization it is far more valuable to observe natural development which can bring something unique rather than influence observation. Likewise regarding nature, we have stopped colonizing Earth and are focusing on more concentrated settlements, density rather than expansion.

As to First Contact. If it happens, I suspect it will be through a fleet of hypertelescopes detecting night lights on planet couple of thosuands light years away, or some megascale engineering project in deep space or galactic core. Or perhaps craters after cataclysmic war on some far away exoplanet.

Far less dramatic than expected, but life changing for our civilization nevertheless. In any case, science doesn’t always go into direction we anticipated. It was expected that detecting new planets and civilizations will happen with space travel by humans. It is now more likely it will happen through astronomy and telescopes.

Agree, if indeed we aren’t in Michio Kaku’s “anthill next to a superhighway” situtation.

The anthill scenarios are flawed, because the reason the ants don’t know what is going on is because they are not intelligent. We are, and we would see the superhighway, and we would know something is up even if we do not understand what we see at all. Especially then.

Michael – enjoyed the storey. I lack your literary abilities but in outline and thinking from the perspective of anyone who had to make a policy decision about such an event, which would have probably been identified via various military air defence and space scanning systems…

intent + capability = threat. In this case neither intent nor capability (beyond being ahead of ours) are clear. Therefore the threat in indeterminate but potentially considerable.

Opportunity – here is clearly very advanced technology which could be useful to ‘us’ (or a threat if availabe to anyone else).

Risks:

In political terms this is an extremely high risk situation – there is little of substance to tell the populace and much to be gained, potentially, in terms of geo-political advantage, if contact can be contained to only ‘us’ (the USA in this case.

Decision – secure the object if possible. Do not attack except in self defence. Identify any civilian with knowledge of object and prepare options to discredit or otherwise prevent any disclosure. Muddy the water considerably by planting wild rumours of the kind common in extreme pro-UFO circles together with a more credible cover story (e.g. one of our spy satellites has come down etc).

A restricted Special Access Programme would need to be established to analyse the object and determine its intent, capability and as much as possible about its origins, technology etc. This may be a very difficult and long term project if the object is significantly ahead of us technically and / or communication is not achieved.

Any recovered object would need to be very closely guarded secret – the potential opportunities but also risks arising from the technology are too great for any other scenario. Monitor other countries for signs that they may have similar knowledge or programmes. utilise the appropriately extreme level of sceptisism within the scientific community to prevent any serious study of this or similar incidents, perhaps using a few agents of influence or perhaps the wilder elements of the pro-UFO community to scare of serious researchers

In short I think it would be buried – and probably rightly so at this stage of our development.

Eniac said on April 30, 2012 at 1:38:

“The anthill scenarios are flawed, because the reason the ants don’t know what is going on is because they are not intelligent. We are, and we would see the superhighway, and we would know something is up even if we do not understand what we see at all. Especially then.”

Are you entirely sure about this? Not only do I wonder if we would recognize an alien astronengineering project, but I can also see a fair deal of our professional scientists deliberately ignoring such signs. Such celestial megaconstructs would have to be really obvious for humanity to comprehend and admit to at this stage of the game.

And why would an advanced alien intelligence bother with making their work understandable to us and any other equivalent species? More than likely they could care less if we grasp what they are doing or not.

That being said, I cannot say I have seen anything in the astronomical images I have studied that clearly say Hey I’m Artificial!, but then again that could be the point: They are doing the equivalent of us making some cell phone towers look like tall trees, blending in to the natural environment so as not to ruin the cosmic aesthetic. But again that brings up the question, why would they care whether the Universe looks pretty or not?

Please note, I am not trying to be snarky here, I wanted to make this point on a very valid subject.

Wojciech said on April 29, 2012 at 11:52:

“We no longer contact isolated tribes on remote islands, as past experience has proven that such a contact is devestating to their existance. And that’s difference in deveopment measured in thousands of years not in millions.

For advanced civilization it is far more valuable to observe natural development which can bring something unique rather than influence observation. Likewise regarding nature, we have stopped colonizing Earth and are focusing on more concentrated settlements, density rather than expansion.”

LJK replies:

Are we doing those “primitive” tribes a favor by leaving them alone and not bringing them into civilization? Especially since civilization is encroaching just about everywhere and in the end they may not have a choice.

Now in the old days especially before modern science and technology, that probably was a good idea, back when people were even more blatantly prejudiced and outright ignorant and virulent diseases ran unchecked. But now we have medicine and technology that makes life far more bearable and much more fair than ever in the past. So do we share these modern wonders with others or do we leave them to what many think is a paradisiacal life, which in reality is often just the opposite?

This can be extrapolated to the wider Universe. If there are ETI who are more advanced, living lives of comfort, safety, and possess knowledge that makes ours pale in comparison, is it fair to leave us in our “primitive paradise” preserve called Earth, or should we have some of that better life too?

LJK:

It looks like you missed the part where I said, effectively, things we do NOT understand are the ones most likely to capture our attention.

Good point. As I have said elsewhere, we would be guilty of crimes against humanity if we withheld medical care, alone. Or, more basically, food during a famine. Even just withholding knowledge and education would be morally problematic. I have to assume that the assertion of the commenter as to the existence of such a policy is a baseless myth, but I would be willing to reconsider if a concrete example were given.

I think it was Kardashev (of Type I, II, and III civilizations) who said it was possible we were integrating what were actually artificial constructs into our “natural” picture of the universe. In terms of the anthill/freeway analogy the ants might have an awareness of something being present, but they take it has part of their environment and have no idea what it is in human terms.

There may be orders of intelligence (or more broadly speaking mentality) that are as incomprehensible to us as ours would be to ants.

Eniac said on April 30, 2012 at 14:57:

LJK:

And why would an advanced alien intelligence bother with making their work understandable to us and any other equivalent species?

It looks like you missed the part where I said, effectively, things we do NOT understand are the ones most likely to capture our attention.”

My view is that not only are there many things we do not and would not understand in the Universe, that they could be staring us right in the face and we are so cosmically clueless that we would not even think to think “Wait a minute…” Add in the stigma by professional scientists not to assume anything isn’t natural and unintelligently designed first and foremost and we are set back even further in our quest for ETI.

there is writing on her side, after many decades of hard work the linguists finaly crack the code, it says, “Test Kitchen”.

True, but unlike the ants, we do not just ignore what we do not understand.

Or so I think. LJK seems to be of a different opinion. Perhaps there is something incomprehensible staring us in the face, although I find it a little curious that a whole profession whose job it is to understand the world has not noticed it. Perhaps, unlike the ant’s superhighway, it is not staring us in the face but is instead well hidden, but that is another discussion.

I thought the point of the article was to get some short multiple endings actually written. So I wrote and rewrote a draft of 800 words. I am ready to rewrite again and, after having my work checked by a peer writer, to submit it for on-line publication. Of course I would get Michael Michaud’s permission before I used the Artemis partial story he wrote.

I believe that someone (not me) will come forward to publish the short story beginning and possible multiple endings. Here is a more specific suggestion.

Once at least 20 endings have been actually written, an e-book could be compiled and published on line. There would be (1) an editor (who would select the stories), (2) a Big Name to write a forward, (3) the original unfinished story, and (4) perhaps a dozen stories endings with titles. There would be criteria, such as length (1,000 words), a submission deadline (one year from the date of the article), the author’s true name and address (even if written under a pen name). There would also be a small group who would handle finances and reject stories that did not meet the published criteria. Michael Michaud would be a necessary participant, but I do not know which category of worker he would prefer for himself.

My guess is that someone will donate $1,000 to publish it. I suggest charging $5.00 per download. The published authors would share 30% of total revenue received by a specified date. The 70% would go toward expenses. If the revenue exceeded costs, the balance could be offered as a donation to a group that will repeat the process for a short story related to contact with alien civilizations.

“My guess is that someone will donate $1,000 to publish it. I suggest charging $5.00 per download.”

Create a new blog for the purpose of “publishing” the story: cost $0

Publish each ending: cost $0

Each download: cost $0

Welcome to the internetz.

I have been a regular reader at Centauri Dreams for almost 3 years now and I have never posted a comment but I can’t help myself with this particular post. I will assume that the writer created the story to broaden minds and excite possibilities in the hearts of those of us who long to see a viable interstellar mission. I must admit that I found myself disappointed in the use of the evil military trope. It smacks more of x-files but I know that some people are just drawn to that thought process.

I would like to see Centauri Dreams set up and run or maybe have someone else volunteer to run a short story contest with either first contact (from either direction) or exploration of neighboring stars by the first interstellar probe as the primary subject matter. I think this is pertinent to this site, as it would excite possibilities in the heart of the readers.

Ron S,

Thanks for the info on internetz and the $0 cost option.

I am new to on-line writing, and have never created a blog. Is the original work copyrighted? By whom? Even if there is no copyright, doesn’t netiquette require that I get Michael Michaud’s permission before I create a blog that copies, uses, and publishes his entire 4,000-word written work?

HughP,

Michael Michaud’s work is Copyright Michael A.G. Michaud 2007, so yes, you do indeed have to get his permission before using the work. Publishing the work without his permission would be a violation of copyright law.

Thanks for the copyright info. I will not create a blog that violates the copyright.

I agree with the May 1 post in which regular-reader Paul said, “I would like to see Centauri Dreams set up and run or maybe have someone else volunteer to run a short story contest with either first contact (from either direction) or exploration of neighboring stars by the first interstellar probe as the primary subject matter. I think this is pertinent to this site, as it would excite possibilities in the heart of the readers.”

HughP, the blog might still be a viable idea, but it would simply need copyright OK from Michael Michaud. I’m just saying you wouldn’t want to proceed without that.