Mars has always been a tempting destination because of the possibility of life. Thus the fascination of Schiaparelli’s ‘canals,’ and Percival Lowell’s fixation on chimerical lines in the sand. But look what’s happened to the question of life elsewhere in the Solar System. We’ve gone from invaders from Mars and a possibly tropical Venus — wonderful venues for early science fiction — to a vastly expanded arena where, if we don’t expect to find creatures even vaguely like ourselves, we still might encounter bacterial life in the most extreme environments.

Astrobiology will push exploration. This is not to say that objects in deep space aren’t worth studying in their own right, possible life or not, but merely to acknowledge that if we find life on another world, it deepens our view of the cosmos and fuels the exploratory imperative. A ‘second genesis’ off the Earth, once confirmed, would heighten interest in other targets where microbial life might take hold, from the cloud tops of Venus out to the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn. We can’t completely discount even the remote Kuiper Belt in terms of dwarf planets and their possible internal oceans.

Jupiter’s Intriguing Moons

The latest mission news from the European Space Agency makes the point as well as anything. The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission, recently approved as part of the agency’s Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 program, takes us from French Guiana aboard an Ariane 5 to Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, all three candidates for internal oceans. It’s no surprise that the major themes of Cosmic Vision at play here are the conditions for planet formation and the emergence of life.

2022 is the scheduled launch date, with arrival in Jupiter space in 2030, after which the spacecraft will spend three years studying these interesting worlds and reporting back to Earth. The Guardian quotes Leigh Fletcher (Oxford University) in this recent article:

“Scientists have had a lot of success detecting the giant planets orbiting distant stars, but the really exciting prospect may be the existence of potentially habitable ‘waterworlds’ that could be a lot like Ganymede or Europa.

“One of the main aims of the mission is to try to understand whether a ‘waterworld’ such as Ganymede might be the sort of environment that could harbour life.”

The notion of a habitable zone — habitable for human beings — gives way to the much broader ‘life zone’ where some form of life might emerge, and Jupiter offers an extremely useful environment in which to probe it. How does Ganymede’s magnetic field, for example, protect it from the hostile radiation belts spawned by the solar wind interacting with Jupiter’s huge magnetosphere and Io’s plasma? How do Europa and Callisto compare to what we’ll find on Ganymede, and which of the three is most likely to offer conditions in which life might prosper?

Assessing the Radiation Risk

The JUICE mission will make flybys of Callisto and Europa in search of answers, making the first measurements of the thickness of Europa’s crust. It will then enter into orbit around Ganymede in 2032 to study both the surface and internal structure of the moon, the only one in the Solar System known to generate its own magnetic field. You can find ESA’s matrix of science objectives here. Following its selection, the mission now enters a definition phase lasting 24 months. As you might guess, radiation is a major concern, with a late 2011 technical report noting that a shielding analysis should be carried out as soon as possible and a major effort put into shielding simulations to clarify the impact radiation protection will have on payload:

Since 2008 a development was conducted which re-analysed all available in situ measurement data from all missions that visited the Jupiter system (gravity assist and the mission that orbited Jupiter, Galileo), but using primarily Galileo data. The locations of these measurements were first mapped into the Jupiter magnetic field and then parameterised This so called JOREM model was just concluded and validated… at the beginning of the Reformulation Study and was therefore taken as the new baseline. The mean level prediction of the environment by JOREM is higher than the previously used model by about a factor of 2. Furthermore Europa flybys were added to the mission profile, increasing the total dose by about 25%. In comparison, the Callisto phase is only contributing about 9% to the total dose.

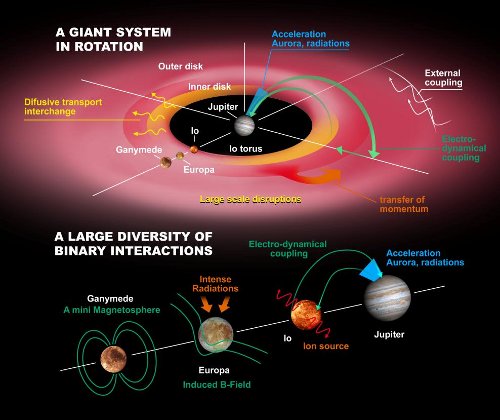

Image: Electrodynamic interactions play a variety of roles in the Jupiter system: generation of plasma at the Io torus, magnetosphere/satellite interactions, dynamics of a giant plasma disc coupled to Jupiter’s rotation by the auroral current system, generation of Jupiter’s intense radiation belts. Credit: ESA.

The effects of intense radiation on glasses, fibre optics and other optical and electro-optical components all come into play here, just as they do in the astrobiological questions that go beyond the issue of building the spacecraft. The interaction between the Galilean moons and Jupiter itself through gravitational and electromagnetic forces will be illuminating as we look at the question of possible life in these ‘water worlds.’ From the ‘Yellow Book’ report on JUICE, which contains the results of ESA’s assessment study of the mission:

…organic matter and other surface compounds will experience a different radiation environment at Europa than at Ganymede (due to the difference in radial distance from Jupiter) and thus may suffer different alteration processes, influencing their detection on the surface. Deep aqueous environments are protected by the icy crusts from the strong radiation that dominates the surfaces of the icy satellites. Since radiation is more intense closer to Jupiter, at Europa’s surface, radiation is a handicap for habitability, and it produces alteration of the materials once they are exposed…

That difference will be useful as we compare and contrast the three moons for potential astrobiology. And the differences affect the instruments needed to do the job:

The effect of radiation on the stability of surface organics and minerals at Europa is poorly understood. Therefore, JUICE instrumentation will target the environmental properties of the younger terrains in the active regions where materials could have preserved their original characteristics. Measurements from terrains on both Europa and Ganymede will allow a comparison of different radiation doses and terrain ages from similar materials. The positive side of radiation is the generation of oxidants that may raise the potential for habitability and astrobiology. Surface oxidants could be diffused into the interior, and provide another type of chemical energy…

I’ve focused on radiation here as simply one of the major issues that makes Jupiter such an interesting target when we’re looking at astrobiological possibilities. The Yellow Book report says the Galilean satellites “…provide a conceptual basis within which new theories for understanding habitability can be constructed.” Voyager and Galileo have given us enough of a look at these worlds to know how much we will benefit from an orbiter around Ganymede, even if a far more radiation-hardened Europa orbiter isn’t yet in the cards. But we do get the Callisto and Europa flybys with JUICE, and the path ahead is clearly defined as we try to set needed constraints on the emergence of life on icy satellites in our own Solar System and around other stars.

Any evidence of life off earth would be an exciting find. Whether this life is a true 2nd genesis, or is related to earth life would make for some very interesting science. Assuming this life must include bacterial life, it seems to me that a sample from Enceladus’ geysers would be an obvious mission that could make direct tests for such life, rather than the proxy experiments for the JUICE mission.

If we did find a 2nd genesis on/in an icy moon, the “warm pond” theory of the origin of life clearly becomes just one possible mechanism in the light of a finding on a cold body.

But one also has to ask, if life originated on Earth, or possibly even Mars, why hasn’t it successfully spread to cold moons via asteroid bombardment and eventual seeding of these bodies by fragments that escaped? If conditions on an icy moon are so different that Earth life could not survive, then are we even looking for the right signs of life on these bodies?

On Earth, life has left an unambiguous mark in geology. We don’t need to detect carbon macromolecules to know that life existed in on teh ancient earth. Is there some other indication that might be obvious (perhaps only in hindsight) on these moons?

To quote from the article:

“The JUICE mission will make flybys of Callisto and Europa in search of answers, making the first measurements of the thickness of Europa’s crust.”

Don’t we already have a pretty good idea that Europa’s ice crust is not nearly as thick as originally thought? See here:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=6351

If drilling/digging/melting through that alien ice is too much for even near-future technology, we may not have to: I am willing to bet that brown material seen all over Europa’s surface is at least organic if not something even more complex and interesting. Just land our probe along one of the cracks and analyze. The cracks may be even thinner areas to access the global liquid ocean beneath if we are still determined to get to it.

I do not see the enveloping radiation from Jupiter as a hazard to Europan life; rather I think it has probably done a lot to make it happen there! And the ice is probably thick enough to keep the radiation from becoming too dangerous for native organisms, at least the ones in the ocean.

We will be thrilled to find even dead creatures on Europa, though it would not surprise me if there is life on and in the ice that has adapted and evolved to handle the harsh environment, as life is often wont to do.

As for Ganymede and Callisto, their liquid oceans probably are buried under numerous miles of ice. Getting to those alien waters will be a real challenge. I wonder if their oceans are even more friendly to life than Europa’s?

Just like with Lake Vostok in Antarctica, it will be interesting – to put it mildly – to see what may have developed for millions if not several billions of years in isolation from the rest of the Universe.

Keep in mind that some scientists think even Io may have life under its surface – Away from the erupting volcanoes and lakes of liquid sulfur at least. If life can exist there, then the rest of the Galilean satellites are virtual ecological paradises by comparison.

Do you guys remember JIMO (Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter)

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/jimo/

*sigh*

I think the focus on Ganymede is mainly for technical (radiation exposure) rather than scientific – yeah, it has a salty ocean, but the crust is very thick. Europa has a thinner crust and this orbiter could get a better estimate at the thickness (which is still in doubt) and the type of material under the crust – liquid water ocean, slushy warm ice or something in between. It could also examine the surface for organics that shouldn’t be there.

@ljk

While I understand that Nasa must have a mission with a definite “task”, I do think they make things unnecessarily hard for themselves. [ Scooping up surface organics might be one way to go (although I wonder it it will prove different than surface materials on comets and outer system icy bodies)]. If Nasa was to look for ancient life on Earth, I suspect they would design a mission with earth moving equipment to dig for fossils, rather than looking for fossils exposed on the surface. Taking advantage of unusual conditions that bring samples within easy reach seems to be difficult for Nasa, perhaps because this requires broad coverage with many machines traversing large areas.

On earth, if the only environment to search was the ocean, the simplest experiment would be to drop a piece of cement into the ocean and retrieve it after 6 months. It will be covered in macro-life that a simple lens would show has a wealth of organisms.

We need to think of more tricks like that for life seeking space missions.

Two fly-bys of Europa 35 years after the ocean was more or less confirmed by Galileo in the mid nineties is a pretty miserable result. At least ESA does not tend to cancel missions easily, so it might actually happen. NASA proposed and cancelled 3 missions to Europa in the last 15 years (Europa Orbiter to be there in 2008 :-), JIMO and a joint mission to ESA).

Enceladus, Titan and Europa are much more interesting than Ganymede but ESA does not have RTGs and can’t do the first two. It also has limited radiation hardened electronics and that explains the paltry two fly-bys of Europa.

NASA allocates a disproportionate amount of funds to Mars. If Curiosity does not find some decent signs of biological activity/interesting organics, then there should not be a $6B program for sample return at the expense of everything else.

A fundamental difference between the ocean on Europa and the oceans on Ganymede and Callisto is the lower boundary: Europa’s ocean is thought to be in direct contact with the rocky core while the oceans on Ganymede and Callisto are probably sitting on top of high-pressure ice phases. I suspect this will make it less likely that the latter two have life because of the differences in delivery of minerals to the ocean.

Nevertheless Ganymede is an interesting target: for example it is currently the only known example of a moon with an intrinsic geomagnetic field. This may provide some kind of analogue to the situation of Earth-type habitable moons orbiting gas giants, if these actually exist.

I for one am delighted that ESA has elected to modify and continue with this mission despite NASA dropping out. For me NASA is losing its vision somewhat and I believe the stage is set for ESA to become the world’s leading Space Agency. But then I am European :). Seriously though, it is excellent to see that we are no longer dependant on the US for the exciting missions. If only Russia can get back to a more reliable level we could be in for some treats over the next half century. I wonder if there’ll ever be a large scale co-operative between ESA, NASA and Roscosmos to make a converted effort to locate life within our Solar Sustem?

Just wondering about the ‘second genesis’ idea, and trying to picture in my mind how life would have begun here in Earth.

On the one hand, did life began on Earth once? By that I mean exactly once, in one place, in one watery home (or wherever)? In this scenario, accounting for the spread of life from a singular genesis to dominating the planet would include some fancy mathematics and biology, both, at that level, beyond my ken.

On the other hand, if life sprouted here on Earth in many different places, and at many different times, the picture changes dramatically. For one, this scenario could have life still forming, even today, depending on many factors beyond this comment.

And, in this second alternative, life would have sprouted in so many different places that predicting extraterrestrial life gains firmer footing indeed.

Is there a third alternative?

I’m a little surprised that nobody has mentioned JUNO. If successful, that mission should tell us a lot more about the radiation environment around Jupiter (and how to build probes to withstand it).

Also, note that Galileo — a probe built with ~1980 technology — survived around Jupiter for 7 years, including multiple flybys of Io and Europa. To be fair, the Io flybys were wisely scheduled near the end of the mission, and resulted in irreparable radiation damage to the cameras. Still: the thing was doable, and with a probe built during the Carter administration.

Doug M.

AstroBadger said on May 9, 2012 at 4:53:

“I for one am delighted that ESA has elected to modify and continue with this mission despite NASA dropping out. For me NASA is losing its vision somewhat and I believe the stage is set for ESA to become the world’s leading Space Agency. But then I am European :). Seriously though, it is excellent to see that we are no longer dependant on the US for the exciting missions.”

LJK replies:

Remember Ulysses? It was part of a joint effort with NASA to send two probes in wide elliptical orbits to examine both poles of the Sun. NASA backed out to focus on the Space Shuttle but ESA hung in there and the results were a probe that not only gave us some of our first detailed examinations of the solar poles but also the space above and below the ecliptic and even several flybys of Jupiter!

http://sci.esa.int/science-e/www/area/index.cfm?fareaid=11

AstroBadger then said:

“If only Russia can get back to a more reliable level we could be in for some treats over the next half century. I wonder if there’ll ever be a large scale co-operative between ESA, NASA and Roscosmos to make a converted effort to locate life within our Solar Sustem?”

I would like to see Russia get back in the deep space game, but they have to really improve their infrastructure after the whole Phobos-Grunt debacle, which also cost the Chinese their first Mars orbiter by default and ruined an experiment designed by The Planetary Society to see if panspermia between worlds is possible.

http://www.planetary.org/explore/projects/life.html

Will Russia ever get enough funding and keep the right people to start exploring beyond Earth orbit properly? Heck, will NASA be able to do the same, especially if Romney wins the 2012 elections? US and ESA Mars missions are already in jeopardy after Curiousity: We may have another situation as with Viking when it did not confirm any signs of life on the Red Planet – almost two decades of no successful missions to Mars.

Enzo said on May 8, 2012 at 17:55:

“Two fly-bys of Europa 35 years after the ocean was more or less confirmed by Galileo in the mid nineties is a pretty miserable result.”

LJK replies:

You said it. And Titan and Enceladus won’t be explored until even later! All of these missions and more could be easily paid for if government authorities wanted to, bad economy or not. They would also create more jobs, stimulate education, and make us all that much smarter about certain parts of the Universe. We might even learn that there is life beyond Earth, gasp!

Humanity’s priorities are out of whack, to put it mildly. And remember the economic crisis was human-made, not some natural disaster or “Act of God” we could not control. That also means it has human-made solutions, but obviously no one in power is in any kind of a real rush to work together and fix things. The last time we had an economic crisis, it took a world war to get us out of it – not sure that plan would go over as well this time without dire consequences.

So let’s try boosting our space programs, government and private, and see what happens. Some rich guys want to mine the planetoids, so there is a real focus for us that is both practical and enlightening.

Enzo then said:

“At least ESA does not tend to cancel missions easily, so it might actually happen. NASA proposed and cancelled 3 missions to Europa in the last 15 years (Europa Orbiter to be there in 2008 :-), JIMO and a joint mission to ESA).”

LJK replies:

Some ExoMars plans are still up in the air, but it looks like ESA will be working with Russia to make it happen before the end of this decade:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ExoMars

Enzo then said:

“NASA allocates a disproportionate amount of funds to Mars. If Curiosity does not find some decent signs of biological activity/interesting organics, then there should not be a $6B program for sample return at the expense of everything else.”

LJK replies:

A Mars Sample Return mission is quite complex and will be very expensive so you may not have to worry about it happening. With the amount of money and resources that would be spent on such a mission, which would return perhaps a few pounds of Martian surface at best after all that effort, you might as well send a manned expedition which would return many pounds of rocks and regolith from a much wider area, just like Apollo did with the Moon.

The Soviets tried to best Viking with a Mars Sample Return mission in the 1970s and the result was no mission and damage to several other of their lunar and planetary efforts:

http://www.astronautix.com/craft/mars5m.htm

As I said in another recent comment on this blog, if Curiousity does not find signs of life or even actual organisms, fossilized or living, this may curtail Mars exploration for a good while, just like what happened when Viking didn’t detect any obvious life signs.

I think Mars has many other interesting aspects and features besides life that should be explored. This goes with so many other places in our Sol system. As much as I am an advocate for extraterrestrial life, I find it unfortunate that most deep space missions are based mainly on looking for alien life and are considered failures if they find none or are put on the shelf if that is not their main focus and goal.

There may be extraterrestrial life in the Sol system, but as we should have learned with Viking, we need to better understand these other worlds first before we plung in hoping for little native critters and then backing out for decades in disappointment when none seem obvious.

The same thing is done to SETI, with people whining about no aliens signalling us after just fifty years of mostly sporadic searches – and the sporadic behavior continues with ATA due to its poor budget management, as it is now focused on looking for space junk in Earth orbit via the USAF.

An ESA launch date 10 years from now is pretty pathetic. But NASA’s even worse – it has no planetary new starts planned at all!

It is indeed conceivable that life may have sprouted multiple times on Earth, but we can be certain that all but one of the independent branches have died out. This is because it is well established that all the life we have ever found is descended from a single ancestral organism. Even if life were to sprout often, we would never know because newly formed lifeforms would be ill-equipped to compete against more refined, existing ones and would be quickly nipped in the bud.

The only way to answer this question is to seek extraterrestrial life. The Earth is much too contaminated with the one form we know.

Monday, September 24, 2012

A More Awesome Europa Clipper Proposal

One of NASA’s key advisory committees, the Committee onAstrobiology and Planetary Science (CAPS), is meeting today and tomorrow. My schedule permits me to listen to just part of the meeting, but I’ve arranged to listen in to two key portions: Today’s update on the Europa Clipper proposal and tomorrow’s presentation on the future Mars roadmap. (Casey Dreier of the Planetary Society is also blogging on the meeting and covers sessions I couldn’t attend.)

The Europa Clipper is one of three mission concepts to come out of the demise of NASA’s Jupiter Europa Orbiter proposal that would have cost close to $4B. That sticker shock led the Decadal Survey to recommend that NASA investigate cheaper mission alternatives. In previous posts, I’ve describe the minimalistic orbiter and a multi-flyby spacecraft (now dubbed, Europa Clipper) and concepts for Europa landers.

Both the orbiter and the Clipper concepts have been estimated to come in at below $2B, meeting the challenge of the Decadal Survey. The science community has favored the Clipper proposal with its richer instrument set over the orbiter. (The lander concept is both much more expensive and requires either the orbiter or Clipper mission to scout for safe and interesting landing sites.) In today’s CAPS meeting, an update to the Clipper concept was provided.

http://futureplanets.blogspot.com.es/2012/09/a-more-awesome-europa-clipper-proposal.html

17 October 2012

** Contact information appears below. **

Text & Images:

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2012-328

JUPITER: TURMOIL FROM BELOW, BATTERING FROM ABOVE

Jupiter, the mythical god of sky and thunder, would certainly be pleased at all the changes afoot at his namesake planet. As the planet gets peppered continually with small space rocks, wide belts of the atmosphere are changing color, hotspots are vanishing and reappearing, and clouds are gathering over one part of Jupiter, while dissipating over another. The results were presented today by Glenn Orton, a senior research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences Meeting in Reno, Nev.

“The changes we’re seeing in Jupiter are global in scale,” Orton said. “We’ve seen some of these before, but never with modern instrumentation to clue us in on what’s going on. Other changes haven’t been seen in decades, and some regions have never been in the state they’re appearing in now. At the same time, we’ve never seen so many things striking Jupiter. Right now, we’re trying to figure out why this is all happening.”

Orton and colleagues Leigh Fletcher of the University of Oxford, England; Padma Yanamandra-Fisher of the Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colo.; Thomas Greathouse of Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio; and Takuyo Fujiyoshi of the Subaru Telescope, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, Hilo, Hawaii, have been taking images and maps of Jupiter at infrared wavelengths from 2009 to 2012 and comparing them with high-quality visible images from the increasingly active amateur astronomy community. Following the fading and return of a prominent brown-colored belt just south of the equator, called the South Equatorial Belt, from 2009 to 2011, the team studied a similar fading and darkening that occurred at a band just north of the equator, known as the North Equatorial Belt. This belt grew whiter in 2011 to an extent not seen in more than a century. In March of this year, that northern band started to darken again.

The team obtained new data from NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility and the Subaru Telescope on Mauna Kea that matched up that activity with infrared observations. Those data showed a simultaneous thickening of the deeper cloud decks, but not necessarily the upper cloud deck, unlike the South Equatorial Belt, where both levels of clouds thickened and then cleared up. The infrared data also resolved brown, elongated features in the whitened area called “brown barges” as distinct features and revealed them to be regions clearer of clouds and probably characterized by downwelling, dry air.

The team was also looking out for a series of blue-gray features along the southern edge of the North Equatorial Belt. Those features appear to be the clearest and driest regions on the planet and show up as apparent hotspots in the infrared view, because they reveal the radiation emerging from a very deep layer of Jupiter’s atmosphere. (NASA’s Galileo spacecraft sent a probe into one of these hotspots in 1995.) Those hotspots disappeared from 2010 to 2011, but had reestablished themselves by June of this year, coincident with the whitening and re-darkening of the North Equatorial Belt.

While Jupiter’s own atmosphere has been churning through change, a number of objects have hurtled into Jupiter’s atmosphere, creating fireballs visible to amateur Jupiter watchers on Earth. Three of these objects — probably less than 45 feet (15 meters) in diameter — have been observed since 2010. The latest of these hit Jupiter on Sept. 10, 2012, although Orton and colleagues’ infrared investigations of these events showed this one did not cause lasting changes in the atmosphere, unlike those in 1994 or 2009.

“It does appear that Jupiter is taking an unusual beating over the last few years, but we expect that this apparent increase has more to do with an increasing cadre of skilled amateur astronomers training their telescopes on Jupiter and helping scientists keep a closer eye on our biggest planet,” Orton said. “It is precisely this coordination between the amateur-astronomy community that we want to foster.”

Contact:

Jia-Rui Cook

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

+1 818-354-0850

jccook@jpl.nasa.gov

The California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, operates the Jet Propulsion Laboratory for NASA.

NEWS by Kelly Beatty

“Black Rain” on Callisto and Ganymede

Computer simulations show that tiny particles drifting inward from Jupiter’s most distant moons — tiny bodies with oddball orbits — could have darkened the surfaces of the two biggest Galilean satellites with deep drifts of dark debris.

Full article here:

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/news/Black-Rain-on-Callisto-and-Ganymede-192179541.html

To quote:

“Europa should have a dark layer at least 35 feet (10 m) thick, but it’s not there — at least not topside. The simplest explanation is most of the “black rain” has gotten churned into the interior by the active geology that continues to reshaped this moon’s surface. Conceivably, the researchers speculate, some of the dark stuff could have reached Europa’s subsurface ocean, infusing it with organic compounds such as amino acids.”