Thinking of Ray Bradbury, as I suppose most of us were yesterday after learning of his death, I found my reminiscences of his work mixing with what was to have been today’s topic, solar sails and their beamed sail counterparts. I’ve read almost all of Bradbury’s work up through the 1960s and admittedly little after that, but he’s a writer I return to often to try to recapture the early magic. I was going through his stories trying to think of one involving solar sails and I came up blank, but in a moment of pure serendipity, I realized that a book I mentioned yesterday held a little Bradbury gem that was all about sails and their implications for the human imagination.

The book is Arthur C. Clarke’s collection Project Solar Sail (Roc, 1990), which contains a poem Bradbury wrote with Jonathan V. Post called “To Sail Beyond the Sun: A Luminous Collage.” Like so much of Bradbury’s work, it uses language like witchcraft to pull you into the experience, and like so much of the later Bradbury, it’s a bit overwrought in places, yet when it hits the right note — and it does this more often than not — the poem weaves a kind of enchantment:

And so we earn what we shall dare

Tossed from the central sun

We with our own concentric fires

Blaze and burn

Burn and blaze. Until we feel

Once at the hub of wakening

the vast starwheel…

Of course, it’s hard to separate out what is Bradbury’s and what his co-author’s work, but the Bradbury lyricism is the dominant force, a deep music that goes back to his pulp magazine days. That music offers the rich counterpoint to The Martian Chronicles, themselves composed as short stories for the magazine market before being assembled into a coherent sequence. In places in this poem there is a taste of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and in both Hopkins and Bradbury an echo of the sturdy alliterative line that drove early Anglo-Saxon verse. You can hear that in places like this:

Small sparks, large sun —

All one, it is the same.

Large flame or small

as long as my heart is young

the flavor of the night lies on my tongue…The Universe is thronged with fire and light,

And we but smaller suns which, skinned, trapped and kept

where we have dreamed, and laughed, and wept

Enshrined in blood and precious bones,

with heartbeat’s rhythms, passion’s tones

Hold back the night…

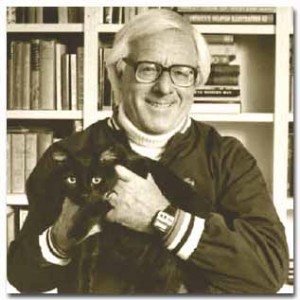

I came to Ray Bradbury through a 1955 collection called The October Country, a battered paperback copy of which I still have on my shelves. It was a challenging approach for a boy who had never encountered what a deft writer could do with the macabre — many of these tales were written for Weird Tales (they later appeared as part of a collection called Dark Carnival before finding their way into The October Country) and they pushed psychic buttons I didn’t know existed. I particularly recall “Skeleton,” a story about a man who develops a phobia about the bones inside his body, and “The Jar,” which caused me to put the book aside for a week before working up the nerve to see what could possibly follow it. I would have been about ten at the time.

Bradbury had a long career in the pulps, and somewhere in this office I have a copy of “Pendulum,” his first professionally published story, which appeared in Super Science Stories in November of 1941. Of course, he would soon move into the glossy magazines and win acclaim for the prescient and eerie fiction of The Illustrated Man (1951) and Fahrenheit 451 (1953) and soon he was a cultural icon, working for Hollywood, producing plays, poems and essays and always turning out his 1000 words a day, a practice he recommended in Zen and the Art of Writing (1990). I taught The Martian Chronicles a couple of times while working as a teaching assistant at a university and loved introducing new readers to his sense of language.

John Scalzi wrote about his first experience with The Martian Chronicles in an introduction to the Subterranean Press edition, available online as Meeting the Wizard:

The Martian Chronicles is not a child’s book, but it is an excellent book to give to a child—or to give to the right child, which I flatter myself that I was—because it is a book that is full of awakening. Which means, simply, that when you read it, you can feel parts of your brain clicking on, becoming sensitized to the fact that something is happening here, in this book, with these words, even if you can’t actually communicate to anyone outside of your own head just what that something is. I certainly couldn’t have, in the sixth grade—I simply didn’t have the words. As I recall, I didn’t much try: I just sat there staring down at the final line of the book, with the Martians staring back at me, simply trying to process what I had just read.

Obituaries are out there by the score, like this one in the New York Times and another good one in The Guardian, so there is no need to run through all the statistics. But it’s fun to hear the stories around the edges. Back in 2006, the public library in Fayetteville, AR was highlighting Fahrenheit 451 in a city-wide ‘Big Read’ event. Bradbury was corresponding with the assistant director of the library about all this and in the process reminisced about the composition of “The Fireman,” the short story from which Fahrenheit 451 would eventually grow. Shaun Usher recently reprinted the letter on his wonderful Letters of Note site, from which I quote:

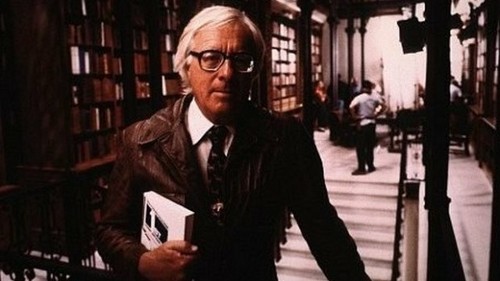

I needed an office and had no money for one. Then one day I was wandering around U.C.L.A. and I heard typing down below in the basement of the library. I discovered there was a typing room where you could rent a typewriter for ten cents a half hour. I moved into the typing room along with a bunch of students and my bag of dimes, which totaled $9.80, which I spent and created the 25,000 word version of “The Fireman” in nine days. How could I have written so many words so quickly? It was because of the library. All of my friends, all of my loved ones, were on the shelves above and shouted, yelled and shrieked at me to be creative. So I ran up and down the stairs, finding books and quotes to put in my “Fireman” novella. You can imagine how exciting it was to do a book about book burning in the very presence of the hundreds of my beloveds on the shelves. It was the perfect way to be creative; that’s what the library does.

This morning my newspaper contains an account of Bradbury’s distrust of colleges and universities. He liked libraries better and thought they were the place to learn, the place where he could tap the energies of the great writers who had gone before and fine-tune what he called his “passionate output.” Passionate it was, and so was the man in every respect. Just last week he appeared in The New Yorker to discuss his inspiration, describing his frenzy over reading early issues of Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories and remembering in particular one magic discovery that would change his life:

My next madness happened in 1931, when Harold Foster’s first series of Sunday color panels based on Edgar Rice Burroughs’s “Tarzan” appeared, and I simultaneously discovered, next door at my uncle Bion’s house, the “John Carter of Mars” books. I know that “The Martian Chronicles” would never have happened if Burroughs hadn’t had an impact on my life at that time.

I memorized all of “John Carter” and “Tarzan,” and sat on my grandparents’ front lawn repeating the stories to anyone who would sit and listen. I would go out to that lawn on summer nights and reach up to the red light of Mars and say, “Take me home!” I yearned to fly away and land there in the strange dusts that blew over dead-sea bottoms toward the ancient cities.

So much of what we try to do here involves engaging the imagination. Neil deGrasse Tyson likes to quote Antoine de Saint-Exupéry on the topic: “If you want to teach someone to sail, you don’t train them how to build a boat. You compel them to long for the open seas.” Ray Bradbury was not a boat-builder, and in his science fiction he was content to leave the details of construction to others. His driving wish, deep and unquenchable, was to awaken in his readers the same passion for raw experience he found within himself, by invoking the small events that define all our lives. Midnight carnivals, small town summers and rockets cutting into the dawn became his working materials, lighting fires that for many of us will burn long after he is laid to rest.

My favorite Bradbury is his collection, “R is for Rocket”. Some of the passages can still move me to tears with their poignancy.

I’ve always wondered why Bradbury was excluded from the “big three” of SF (Clarke, Asimov & Heinlein). His influence is probably at least as great as these others, albeit possibly less for “ideas” than style.

“Transit of Earth” shredded my psyche.

Paul very nice commentary on one of the “Greats”. He was an author who as you said it best, “awaken in his readers the same passion for raw experience he found within himself”. Maybe in the end it’s best to be thankful to the person who made such an impact, instead of being sad for their loss. Rest in peace Mr. Bradbury and may you be ‘home’ now.

Peaceful journeys Ray- Your stories filled my youthful imagination and your wisdom still inspires . Your myths live on and will not only be remembered but will evolve with us as we evolve as a species and as a civilization.

If we do travel to the stars it will be in part because of the you and part of you will be with us.

I loved Ray more than any of the “big three”, as he had the most highly developed sense of the future as dystopian – developed while living on the bleeding edge of western culture in Los Angeles. He was a humanist, and clearly perceived the threat of a mechanised culture to the human spirit. Much of his writing was nostalgia for the pre-war lifestyle, already being radically transformed (and not in an entirely good way) in the 1950s. The Martian Chronicles are mainly about the vulgar Earth people and their consumer culture destroying Mars in an echo of the consequences of the European conquest of native Americans. Some of my favourites:

1) A short story about an innocent man being incinerated by a robotic police cruiser for the suspicious activity of being a pedestrian in a city where no one walks anywhere anymore. No longer SF in a world where 30,000 flying drones, some with offensive capabilities, are to soon be in America’s skies.

2) A short story about a man who is murdered by his smart home appliances after destroying one of them out of annoyance. I understand. Only the fear of consequences restrained me from assaulting the cheerful chatty automated supermarket checker today.

3) The Farenheit 451 passages about dull minded wide screen TV watching people becoming tools of the police state as they become reality TV participants in live police chases. Spot on. Now a CCTV camera droid!!! (I am not making this up) is the cutesy mascot of the London 2012 Olympics and “Big Sister” Napolitano admonishes Walmart shoppers from a giant screen to “say something” if they “see something”.

Tip of the hat to Heinlein, he saw the only hope for human freedom as infinite expansion into space, as free spirits could ride rockets to stay ahead of the ever expanding police state, always seeking total control.

The following is quoted from the Wikipedia writeup on Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451:

“Fire chief Captain Beatty personally visits Montag and tells him the story of how books lost their value and where the firemen fit in: Over the course of several decades, people embraced new media, sports and a quickening pace of life. Books were ruthlessly abridged or degraded to accommodate a short attention span. The government did not start the censorship; it merely exploited the situation. The original books were declared offensive to minority groups, and firemen were given the task of eradicating this threat to public happiness.”

Full article here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fahrenheit_451

Started reading SF when I was 13 and of course was hooked by Heinlein.

I scarfed up Asimov and Clarke…. But in the mid 1950’s there was not a whole lot of SF in book form, lot of magazines … 3 or 4 or them were very good…. An number of bad pulps that revived after WWII… not very good.

There were a number of anthologies that collected very good short stories from the 40’s and 50’s.

It’s funny I noticed some books by Ray Bradbury… my SF buddies didn’t really like him.

I read the Martian Chronicles , yeah I could see ol Ray didn’t know beans about science!

Still I liked the book. Read all his short stories in the 1950’s.

Early on he only had a couple of novels , Fahrenheit 451 and Something Wicked This Way Comes ….

He wrote later novels that I didn’t care for… but almost all the collections of his short stories are good.

A remarkable writer, I like John Huston’s version of Moby Dick (it kind of got hammered at the time, why I don’t know.)

Bradbury wrote the screenplay … and a very funny memoir about his experience in working on the film, and a scathing critique of Huston as a person.

Huston never could succeed at have ‘a go at Bradbury’ and accomplishment in itself!

I met him once, shook his hand,…. I didn’t even get his autograph. O well.

He is almost the last of the 2nd generation , should I call them Golden Agers?

… Fred Pohl is still about, but not in good health, Jack Vance seems hardy …

a few others… not many left.

Ray Bradbury was easily the most atmospheric writer out of the well known classic SF writers, Asimov, Clarke and Heinlein. Some of is stories genuinely scared me as a kid.

There’s one short story that I half remember that is driving me mad, because I can’t remember in which book I read it. Very scary (or at least it was when I was 11), set in Mexico. I can’t even remember what it was about, other than the Mexico connection. Has anyone any suggestions?

Joy said on June 7, 2012 at 23:27:

“Tip of the hat to Heinlein, he saw the only hope for human freedom as infinite expansion into space, as free spirits could ride rockets to stay ahead of the ever expanding police state, always seeking total control.”

Those and several other “antisocial” types are most likely the first kinds of humans who will venture to the stars, assuming humans are the ones who personally engage in this activity. Just as the first expeditions to the New World from Europe were Vikings, fishermen, treasure seekers, and missionaries, not noble scientists.

As for Bradbury’s other stories, I recall among many the one about the guy who is in a mental institution because he cleverly destroyed all his appliances because they were talking to him all day long. He ends up enjoying the peace and quiet of his gadgetless cell, while his therapists walks away shaking his head in pity and incomprehension, while at the same time his devices are telling him about his next appointments, the groceries he needs to pick up after work….

Like Rod Serling, Bradbury was not big on being scientifically accurate in his works, but that was not the point at all. Some of them may strain a bit these days with us being a bit more knowledgable about the Universe than they were (planetoids with breathable atmosphere and blue skies?), but the stories are still timeless and still captivate. Bradbury always did make prose seem like poetry.

kzb said on June 8, 2012 at 11:48

“There’s one short story that I half remember that is driving me mad, because I can’t remember in which book I read it. Very scary (or at least it was when I was 11), set in Mexico. I can’t even remember what it was about, other than the Mexico connection. Has anyone any suggestions?”

Could it be this story from The October Country collection (from Wikipedia):

“The Next in Line”

A couple staying in a small Mexican town comes across a cemetery which holds a shocking policy regarding the interred whose families cannot pay.

That’s the one I was going for too, Larry. I was sure it was from The October Country, but couldn’t come up with the title. Thanks.

NASA remembers Ray Bradbury:

http://www.space.com/16067-ray-bradbury-nasa-video-tribute.html

I highly recommend finding the book Mars and the Mind of Man and I would love to see the complete film of those sessions.

Digital copy of “The Martian Chronicles” on Mars

Published: Jun 6, 2012

http://m.apnews.com/ap/db_21293/contentdetail.htm?contentguid=4N3aizUp

I wrote my own wholly inadequate tribute too:

http://www.tor.com/blogs/2012/06/remembering-ray-bradbury

So long, Ray; I knew you for 40 years, far too few.

There is a charming portrait of Bradbury at the conclusion of Oriana Fallaci’s wonderful book, If The Sun Dies (1966). I wanted to plug that book at some point because in my mind it is superior to that other, better known book on the U.S. Space program, The Right Stuff (1979). Wolfe is a great writer but he couldn’t come close to Fallaci on this one. The closing scene has Bradbury being roundly criticized by his daughters for the scientific inaccuracies in The Martian Chronicles (others would make similar complaints) and of course he takes it well and rises above the situation beautifully. I suspected this was a family game, perhaps sometimes played for guests. It was a brilliant way to end the book and while I came to think of him as a fantasist first (one of the best) and an SF writer rather far down the list, he was always there somewhere in my thinking. In my first year of college I walked (erratic bus routes and no car compelled me) some eight miles to see the film version of Fahrenheit 451. I had to see it. And I am happy to say I loved it (though I’m unsure what he thought of the film). All that walking was perhaps my way of a tribute to him at the time for his influence on me. There are very few authors I would have done the same for, and none these days (not that I’m in the mood to walk sixteen miles on a given day in any event).

http://boingboing.net/2012/06/07/ray-bradburys-original-conce.html

Ray Bradbury’s original concept script for Epcot’s Spaceship Earth

By Cory Doctorow at 6:12 pm Thursday, June 7, 2012

An anonymous reader sent me Ray Bradbury’s 1977 concept script for Spaceship Earth at Epcot Center. It’s a beautiful read, and led me to vivid recollections of the original script from Epcot’s opening in the early 1980s.

MAN AND HIS SPACESHIP EARTH (PDF) (Thanks, Anonymous Reader!)

http://craphound.com/RAY_BRADBURY_ManAndHisSpaceshipEarth1977.pdf

(Image: Spaceship Earth Mural 2, a Creative Commons Attribution (2.0) image from aloha75’s photostream)

Very nice tribute to Ray Bradbury Paul! And, I agree with Tyson’s sailing quote. :-)

ljk and Paul: thanks, I’ll check it out again.

R is for Rocket, S is for Space

by Andre Bormanis

Monday, June 11, 2012

Last week, a few hours after the planet Venus made its transit of the Sun, Ray Bradbury took his leave of the planet Earth. He was an American original, the poet laureate of the Space Age. His writing, perhaps more than that of any other modern author, shaped the way we think about space travel, and America’s role in pioneering it.

Full article here:

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2098/1

To quote:

“When Ray started out, the field of science fiction lacked respectability, to say the least. It was the province of the pulps: magazines printed on cheap paper, with lurid covers designed to catch the attention of immature boys. He was often dismissed, if not outright ridiculed, by mainstream writers, but quickly learned to ignore his critics. If they didn’t think rockets and dinosaurs were suitable subjects for literature, to hell with them. Ray loved that stuff, along with Martians and witches and things that go bump in the night, so that’s what he wrote about. His unique imagination was harnessed within vivid, lyrical prose, and after the publication of The Martian Chronicles in 1950, the literary elite were forced to acknowledge a striking new talent.”

Ray Bradbury’s influence on one career in aerospace

by Jim Knauf

Monday, June 11, 2012

I suspect that for many who live their lives in space and science careers, author Ray Bradbury’s passing last week may evoke the some of the influences that took them down their chosen career path, much as it has recalled my own nostalgia of what turned out to be an especially formative time in my life.

As it happens, I lived for a time in Bradbury’s hometown of Waukegan, Illinois. I was about the same age as he, before he moved to Los Angeles in 1934. That time, that place, and those youthful experiences in that neighborhood—especially in the Waukegan Public library, with its rows of books by Bradbury and others—initiated a foundational love of reading with the endless possibilities it conjures up, a lifelong interest in space and rockets, and eventually a career in aerospace. This is the kind of inspiration we need today to encourage young people to choose space-related careers.

Full article here:

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2097/1

http://todaysinspiration.blogspot.com/2006/09/our-fascination-with-mars.html

Today’s Inspiration – Thursday, September 14, 2006

Our Fascination with Mars

The men of Earth came to Mars.

They came because they were afraid or unafraid, because they were happy or unhappy, because they felt like Pilgrims or did not feel like Pilgrims.

There was a reason for each man. They were leaving bad wives or bad jobs or bad towns; they were coming to find something or leave something or get something, to dig up something or bury something or leave something alone. They were coming with small dreams or large dreams or no dreams at all. But a government finger pointed from four-color posters in many towns:

THERE’S WORK FOR YOU IN THE SKY: SEE MARS! and the men shuffled forward, only a few at first, a double-score, for most men felt great illness in them even before the rocket fired into space. And this disease was called The Lonliness, because when you saw your home town dwindle to the size of your fist, and then lemon-size and then pin-size and vanish in the fire-wake, you felt you had never been born, there was no town, you were nowhere, with space all around, nothing familiar, only other strange men.

And when the state of Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, or Montana vanished into cloud seas, and, doubly, when the United States shrank to a misted island and the entire planet Earth became a muddy baseball tossed away, then you were alone, wandering in the meadows of space, on your way to a place you couldn’t imagine.

Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles, 1950

The man could write, absolutely no doubt about that.

Another one – this time one of my favorite stories, “A Sound of Thunder”:

http://todaysinspiration.blogspot.com/2006/09/sound-of-thunder.html

Mars and the Mind of Man: Carl Sagan, Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke in Conversation, 1971

by Maria Popova

August 20, 2012

On November 12, 1971, the day before NASA’s Mariner 9 mission reached Mars and became the first spacecraft to orbit another planet, Caltech Planetary Science professor Bruce Murray summoned a formidable panel of thinkers to discuss the implications of the historic event.

Murray himself was to join the great Carl Sagan (?) and science fiction icons Ray Bradbury (?) and Arthur C. Clarke (?) in a conversation moderated by New York Times science editor Walter Sullivan, who had been assigned to cover Mariner 9?s arrival for the newspaper.

What unfolded — easily history’s only redeeming manifestation of the panel format — was a fascinating quilt of perspectives not only on the Mariner 9 mission itself, or even just Mars, but on the relationship between mankind and the cosmos, the importance of space exploration, and the future of our civilization.

Two years later, the record of this epic conversation was released in Mars and the Mind of Man (public library), alongside early images of Mars taken by Mariner 9 and a selection of “afterthoughts” by the panelists, looking back on the historic achievement.

“It’s part of the nature of man to start with romance and build to a reality.”

Full article here:

http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2012/08/20/mars-and-the-mind-of-man-sagan-bradbury-clarke-caltech-1971/

To quote:

But by far the most beautiful meditation comes from Ray Bradbury, who transposes his passionate advocacy of writing with joy and excitement onto space exploration as well:

I think it’s part of the nature of man to start with romance and build to a reality. There’s hardly a scientist or an astronaut I’ve met who wasn’t beholden to some romantic before him who led him to doing something in life.

I think it’s so important to be excited about life. In order to get the facts we have to be excited to go out and get them, and there’s only one way to do that — through romance. We need this thing which makes us sit bolt upright when we are nine or ten and say, ‘I want to go out and devour the world, I want to do these things.’ The only way you start like that is with this kind of thing we are talking about today. We may reject it later, we may give it up, but we move on to other romances then. We find, we push the edge of science forward, and I think we romance on beyond that into the universe ever beyond. We’re talking not about Alpha Centauri. We’re talking of light-years. We have sitting here on the stage a person who has made the film* with the greatest metaphor for the coming billion years. That film is going to romance generations to come and will excite the people to do the work so that we can live forever. That’s what it’s all about. So we start with the small romances that turn out to be of no use. We put these tools aside to get another romantic tool. We want to love life, to be excited by the challenge, to life at the top of our enthusiasm. The process enables us to gather more information. Darwin was the kind of romantic who could stand in the middle of a meadow like a statue for eight hours on end and let the bees buzz in and out of his ear. A fantastic statue standing there in the middle of nature, and all the foxes wandering by and wondering what the hell he was doing there, and they sort of looked at each other and examined the wisdom in each other’s eyes. But this is a romantic man — when you think of any scientist in history, he was a romancer of reality.

September 4, 2012 at 11:40 AM 7,658 14

This “lost” interview with Ray Bradbury is the best thing you’ll listen to today

Robert T. Gonzalez

One of Ray Bradbury’s lesser-known interviews also happens to be one of his last, and it is positively wonderful to experience. In 2010, the literary giant was interviewed by Sam Weller (his official biographer) at San Diego Comic Con. The then-89-year-old Bradbury spent a little over an hour ruminating on life, love, space exploration, and even libraries, with the verve and wit of somebody a fraction of his age. It’s as stirring as it is refreshing, and offers a revealing look inside one of the twentieth century’s most inspiring minds.

If you can spare the time, we recommend giving the entire interview, which we’ve included below, a listen. It was recorded by Jeff Goldsmith, publisher of the free storytelling app Backstory, and re-broadcast in a slightly edited form in the days following Bradbury’s passing.

The interview begins around the 2 minute mark, following a short introduction from Goldsmith. If you’re looking for a streamlined version, Maria Popova has excerpted and transcribed some of the most compelling segments of the interview over on Brain Pickings. You honestly can’t go wrong either way, so choose your own auditory adventure, sit back and enjoy.

http://io9.com/ray-bradbury/#13468619524621

A review of a book on the various fiascos in the making of John Carter (of Mars):

http://amazingstoriesmag.com/2013/03/mars-babylon-a-review-of-john-carter-and-the-gods-of-hollywood-by-michael-d-sellers/

After reading the synopsis of how badly Disney handled JC (oM), I am amazed the film turned out as well as it did. At least if there are sequels to the series, they will be done by someone who hopefully gives a flying fig about them.