Anomalies are always fascinating because they cause us to re-examine our standard explanation for things. But in the case of the so-called ‘Pioneer anomaly,’ the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Slava Turyshev, working with a group of scientists led by JPL’s John Anderson, needed an explanation for practical reasons. The possibility that there was new physics to be detected had the scientists wondering about a deep space mission to investigate the matter, but missions are expensive and the case for a genuine Pioneer effect had to be strengthened or else put to rest.

All of this led Turyshev to begin a multi-year data-gathering mission of his own, scouring records related to Pioneer wherever they might be found to see if what was happening to the spacecraft could be explained. The effect was tiny enough that it was originally dismissed as the result of leftover propellant in the fuel lines, but that explanation wouldn’t wash. Something was causing the two Pioneers to decelerate back toward the Sun, a deceleration that was finally measured as being about 300 inches per day squared (0.9 nanometers per second squared).

I love Turyshev’s quote on the matter, as seen in this JPL news release:

“The effect is something like when you’re driving a car and the photons from your headlights are pushing you backward. It is very subtle.”

Subtle indeed, but combing through telemetry and Doppler data, the team made a number of memorable finds, starting with the discovery of dozens of boxes of magnetic tapes stored under a staircase at JPL itself. This one is a story I always cite when talking about the danger of data loss in a time of digital information. Fully 400 reels of magnetic tape were involved, carrying records from the 114 onboard sensors that charted the progress of each of the two missions. All this information had to be transferred to DVD, as did other data from floppy disks that had been preserved at NASA’s Ames Research Center by mission engineer Larry Kellogg.

Image: For old times’ sake (and because these guys are heroes of mine), great figures from the Pioneer era, here seen celebrating after what turned out to be one of the last contacts with Pioneer 10 in 2002 (the final contact was made in January of 2003). Left to right: Paul Travis, Pioneer senior flight controller; Larry Lasher, Pioneer project manager; Dave Lozier, Pioneer flight director and Larry Kellogg, project flight technician. Credit: NASA Ames.

We came just that close to losing the key Pioneer data altogether, a reminder of the need to back up information and convert it into new formats to ensure its preservation. The Pioneers were launched at a time when data were routinely saved on punch cards which were themselves then converted into different formats at JPL, and other information had to be tracked down at the National Space Science Data Center at NASA Goddard in Greenbelt, MD. All told, Turyshev and team collected about 43 gigabytes of data and – a close call indeed – one of the tape machines needed for replaying the magnetic tapes, an item about to be discarded.

In the salvaged files from the Pioneers we learn the secret of the anomaly: Heat from electrical instruments and the thermoelectric power supply produces the effect detected from Earth, or in the words of the recently published paper on this research, the anomaly is due to “…the recoil force associated with an anisotropic emission of thermal radiation off the vehicles.” Take account of the thermal recoil force and no anomalous acceleration remains. If this work stands up, the Pioneer anomaly, well worth investigating because it seemed to challenge our standard model of physics, can be explained in a way that is consistent with that model in every respect.

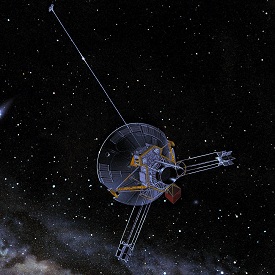

The paper is Turyshev et al., “Support for the Thermal Origin of the Pioneer Anomaly,” Physical Review Letters 108, 241101 (abstract). Credit for the Pioneer image at the top of the page: Don Davis/NASA.

Oh, by the way: this had – in its essence – been known for eleven years. D’oh.

The dedication Slava Turyshev and his colleagues have put into solving the Pioneer Anomaly has been immense – it must surely rank as one of the greatest scientific detective stories. It wasn’t just a matter of finding the old magnetic tapes – computers changed a lot while the Pioneer missions were ongoing. When they launched they were using punch cards, and new computer formats followed one by one, so they had to work out how each set of data had been formatted, using what code and on what type of computer. Paul mentions how some of it had been transferred to digital, which had corrupted it by adding an extraneous piece of code to every file, so Craig Markwardt from Goddard had to go into the code and manually remove that erroneous bit from each and every file.

Then they had to find out the specifics of how the various deep space antennas around the globe had communicated with the Pioneers, the exact positions of the antennas with respect to a given coordinate frame, ramping models that charted the signal strength for a given frequency as the Pioneers receded from us, even local weather conditions at the time that could delay the radio signals slightly. None of this was ever published but luckily they were able to track most of this down in old handwritten notebooks, but it must have been an uphill task and a huge amount of luck to find them after all this time.

While a part of me is disappointed that it didn’t turn out to be new exotic physics, as that would be really exciting, I think the way they seem to have solved the puzzle is beautiful science. Bravo!

Paul, I agree with you this is excellent work. Save data from these old missions is critical. I wish missions were required to have a data archiving strategy from the beginning. It should be part of the original proposals.

Interesting.

Strange how a deceleration of 25 feet per day squared doesn’t seem like much when the velocity of the spacecraft is over 7.5 miles a second! And it’s even more amazing that travelling at 7.5 miles/second won’t get you to another star for tens of thousands of years…

I wonder if these probes are slowed any significant amount by friction from the minute amount of microscopic particles they pass through as they travel through space. I guess they’d encounter so few atoms that the deceleration from “drag” would hardly be measurable?

http://tranquilitybaseblog.blogspot.com/

This work is guaranteed to stand up as long as the data is not released publicly and no future experiments are planned to control for thermal factors. :-(

Thanks, and for those that don’t have access to Physical Review Letters, this is free. http://arxiv.org/abs/1204.2507

LRK

Brie A: 25 feet/day^2 is about 9 micro-g, and imparts about 2.8 metre/s per year of delta-v. I’m surprised it’s this high.

Maybe simple heat radiation from nuclear reactions could become competive with ion drives ?

We don’t have to wait for an actual solar-sail deployment

for experimental verification of optical-momentum theory:

Here is an observable effect, albeit only 0.1 nano-gee,

of tiny flux differentials between the opposite sides of the spacecraft.

Emission, moreover, has half the force of reflection, which sails use.

Congratulations on all that data recovery,

which makes the authors as much historians as scientists.

Slava Turyshev’s gang deserve our thanks. Great work!

Erik Anderson said on July 18, 2012 at 11:49:

“This work is guaranteed to stand up as long as the data is not released publicly and no future experiments are planned to control for thermal factors. :-(”

If the anomaly had proven to be something unexpected and exciting, do you really think the investigators would hide such news? I am smelling conspiracy paranoia here, unless you happen to know something we don’t and can back it up with scientific evidence.

So, in a sense this is an example of a photon rocket…

So, the Pioneer anomaly was caused by the probes acting like a photon rocket? That’s interesting- I wonder how quickly a probe with an actual nuclear powered photon engine could accelerate. Obviously the acceleration of such a “photon engine” would be quite observable, if the anisotropic emission of infrared radiation off of a space probe is enough to confuse researchers on Earth.

I’m not surprised the resolution to the Pioneer Anomaly turned out to be something like this. You can’t jump up and down over the possibility of “new physics” until you have ruled out all the boring explanations that fit with our current framework of physics.

This suggests the “heat anisotropy drive”: A thin sail, black on one side and mirrored on the other, will accelerate from heat radiation alone. It would be interesting to calculate if the heat generated by incoming interstellar gas would generate enough thrust to overcome the very small, but opposite momentum it also generates. Probably not, this idea reeks too much of perpetual motion.

Next up, then, would be making the sail of a radioactive isotope that generates heat for a very long time. Such a two-layer sail would have a black, radioactive layer on a reflective substrate. It could use both alpha and thermal radiation for propulsion.

Note, though, that in no case is the exhaust velocity well matched to the burn-up fraction: Any such system would be much less efficient than the ideal fission fragment rocket.

Cat ‘photon retro rocket’ maybe.

Hmm. Wouldn’t this latent emission be omni-directional?

The saving of data from the Apollo era has proven a real problem too.

From Wiki

“S-IVB-503N Apollo 8 December 21, 1968 Solar orbit

S-IVB-504 Apollo 9 March 3, 1969 Solar orbit

S-IVB-505 Apollo 10 May 18, 1969 Solar orbit

S-IVB-506 Apollo 11 July 16, 1969 Solar orbit

S-IVB-507 Apollo 12 November 14, 1969 Solar orbit; Believed to have been discovered as an asteroid in 2002 and given the designation J002E3”

There are five S-IVBs in Solar orbit and most of the Tran Lunar Injection tracking data for these has been lost.

The tracking data on those big tape reels were stored for a while but many were written over.

I know someone from Apollo days who kept hard copy in his own attic for 40 years , but had to throw it out.

Since the return of the S-IVB from Apollo 12, JPL has been wanting trajectory data to compute their returns to Earth Moon space but it’s difficult.

I know of a one man effort to find the data and compute the orbits, at JSC, but it’s been difficult.

They are an odd ball collision hazard with the Earth. The Moon is also a target, which would be interesting.

A story. When the first Saturn V’s finally allowed Trans Lunar Injection and the Apollo trajectories were Free Return… some one at JSC in Mission Planning and Analysis Division … finally asked , “where does the S-IVB go?

Headquarters had not thought about it! Well… back to Earth!

So a trim burn was done to place the S-IVBs on a swing by of the Moon that placed in Solar Orbit.

(By the by these orbits sort of ‘shadow’ the Earth’s orbit and hence can re-enter Earth-Moon space.)

When seismometers were in place the S-IVBs were targeted to impact the moon , useful test impacts.

This was supposed to happen with Apollo 12, but the trim burn failed and that S-IVB missed and came back to a chaotic orbit in Earth Moon space for about a year, leaving in June 2003. It may be back here in 2032.

The ascent stage of the Lunar Module for Apollo 10 was put in heliocentric orbit in 1969, the only one from an actual space mission still intact. A group started looking for it last year. Read here:

http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-092011a.html

http://www.collectspace.com/ubb/Forum29/HTML/000516.html

And don’t forget Object 1991 VG:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=80

kzb: The anomalous acceleration of Pioneer anomaly was about 9 x 10^-10 m/s^2, or about 900 nano-gee.

That comes out to 2.8 cm/s per year (not m/s).

hey- thsi does nto leave not a lot of room for dark matter in our solar system!

how can the universe be filled with Dark matter but have none here? It is ” the pioneer /Zwicky” paradox

– that is the orbits of stars in the galaxy are anomolous but not planets of our star, the sun. I wonder if this can be proven true for the known exoplanets?

@Andrew Higgins: yes I was working off Brie A’s post, it seemed a bit high to me also !

@jkittle: the amount of DM in the solar system volume I read somewhere is equivalent to about one very small asteroid, and that is distributed within an enormous volume. The implication being, the gravitational effect is too small to measure.

The proposed solution was applied to the Pioneer 10 data, but not to the Pioneer 11 data set. Pioneer 11 exhibits a distinct variation with respect to heliocentric distance during the first 5 years of its mission (the onset of the Pioneer anomaly), and the heat emission model proposed by Turyshev et. al. in their June 2012 paper is unable to account for it. They address this issue at the end of their paper by stating that “In closing, we must briefly mention additional avenues that may be explored in future studies. First, the case

of Pioneer 11 was not analyzed at the same level of detail, albeit we note that spot analysis revealed no surprises for this spacecraft. Second, the question of the anomalous spin-down of both spacecraft remains unaddressed, even though it is plausible that the spin-down is due to heat that is reflected asymmetrically off instrument sunshades. Third, Fig. 2 is strongly suggestive that the previously reported “onset” of the Pioneer anomaly

may in fact be a simple result of mismodeling of the solar thermal contribution; this question may be resolved with further analysis of early trajectory data.”

In other words, since the data for Pioneer anomaly doesn’t fit their model, they claim that the data itself is wrong, not the model. Sounds a bit backwards, don’t you think?

Pioneer Anomaly Solved?

Interstellar Travelers of the Future May Be Helped by Physicist’s Calculations

ScienceDaily (Oct. 9, 2012) — Interstellar travel will depend upon extremely precise measurements of every factor involved in the mission. The knowledge of those factors may be improved by the solution a University of Missouri researcher found to a puzzle that has stumped astrophysicists for decades.

“The Pioneer spacecraft, two probes launched into space in the early 70s, seemed to violate the Newtonian law of gravity by decelerating anomalously as they traveled, but there was nothing in physics to explain why this happened,” said Sergei Kopeikin, professor of physics and astronomy in MU’s College of Arts and Science.

“My study suggests that this so-called Pioneer anomaly was not anything strange. The confusion can be explained by the effect of the expansion of the universe on the movement of photons that make up light and radio waves.”

Full article here:

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/10/121009161103.htm

Finding the Source of the Pioneer Anomaly

Thirty years ago, the first spacecraft sent to explore the outer solar system started slowing unexpectedly. Now we finally know what happened

By Viktor T. Toth, Slava G. Turyshev / December 2012

Some 40 years ago, a quarter-ton lump of circuits and sensors slipped Earth’s surly bonds, sped past the moon and Mars, and hurtled toward Jupiter.

The probe, Pioneer 10, and its sister ship, Pioneer 11, which followed a year later, were true trailblazers. They gave humanity its first close-up glimpses of worlds beyond the solar system’s asteroid belt. They also left behind a mystery—one that has simultaneously baffled and inspired astrophysicists for years.

Like many puzzles, this one started out with just a small hint that something was amiss. Not long after Pioneer 10 and 11 had passed beyond the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn, their navigators began to notice something unexpected. Both spacecraft seemed to be slowing down more than controllers had predicted they would, as if some force were tugging them ever so subtly backward toward the sun.

Full article here:

http://spectrum.ieee.org/aerospace/astrophysics/finding-the-source-of-the-pioneer-anomaly

While Turyshev et al. have probably found the cause of the main Pioneer anomaly, there are several smaller anomalies that go unsolved and are usually just ignored, but are none the less real anomalies.

Specifically there is a strong diurnal (daily) period in the data that is not explained by any theory yet, and a less strong but definite annual period. There are also hints of periods of other lengths in the data. All these remain to be resolved, and it is erroneous, at least in my opinion, to dismiss them as noise of some sort, because they definitely exceed the noise level of the instrumentation. http://arxiv.org/abs/0809.2682