After our recent exchange of ideas on SETI, Michael Chorost went out and read the Strugatsky brothers’ novel Roadside Picnic, a book I had cited as an example of contact with extraterrestrials that turns out to be enigmatic and far beyond the human understanding. I’ve enjoyed the back and forth with Michael between Centauri Dreams and his World Wide Mind blog because I learn something new from him each time. In his latest post, Michael explains why incomprehensible technology isn’t really his thing.

A Sense of the Weird

Why? Michael grants the possibility that extraterrestrial intelligence may be far beyond our understanding. But in terms of science fiction and speculation in general, he favors what he calls ‘the uncanny valley,’ the sense of weirdness we get from a technology that is halfway between the incomprehensible and the known. A case in point is Piers Anthony’s novel Macroscope, in which an alien message overwhelms the minds of those who can understand it (people with IQs in the 150 range), causing some to go into a coma, some to die. Those of average intellect, unable to understand the message, remain unharmed by it.

Chorost explains:

The idea of a mind-destroying concept falls into the uncanny valley. It’s analogous to something we have, but it’s qualitatively, ungraspably better. It echoes Godel’s Theorem, which proves that it, the theorem itself, is unprovable. (I’m oversimplifying here.) A theorem that proves its own unprovability is a fascinating, mindbending thing. It upended mathematics when Godel published it in 1931. I have never understood it myself in a whole and complete moment of insight, and there’s a reason for that; it is fundamentally paradoxical. I can understand the pieces one at a time, but not the pieces put together. It gives me the feeling that if I ever did fully grasp all of it, my mind would be both much smarter, and broken. (Godel in fact went insane toward the end of his life.) The point is, we already know of ideas that probably exceed the mental capacity of most human beings. Macroscope invites us to consider the possibility that even higher-octane ideas would break our minds.

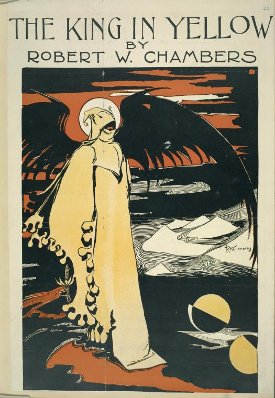

All of which brings to my mind Robert W. Chambers 1895 book The King in Yellow. Chambers was an artist and writer of considerable power. Indeed, Lovecraft biographer S. T. Joshi described The King in Yellow as a classic of supernatural literature, a sentiment echoed by science fiction bibliographer E. F. Bleiler. The book is a collection of unusual tales named after a play that becomes a theme in some, but not all of the stories. With Chambers you have truly entered into the uncanny valley, for when characters in his tales read the fictional play called The King in Yellow, they often go mad. The narrator reads the first act, throws the book into his fireplace and then, seeing the opening words of the second act, snatches it back and reads the entire volume, becoming possessed by its bizarre imagery.

When the French Government seized the translated copies which had just arrived in Paris, London, of course, became eager to read it. It is well known how the book spread like an infectious disease, from city to city, from continent to continent, barred out here, confiscated there, denounced by press and pulpit, censured even by the most advanced of literary anarchists. No definite principles had been violated in those wicked pages, no doctrine promulgated, no convictions outraged. It could not be judged by any known standard, yet, although it was acknowledged that the supreme note of art had been struck in The King in Yellow, all felt that human nature could not bear the strain, nor thrive on words in which the essence of purest poison lurked. The very banality and innocence of the first act only allowed the blow to fall afterward with more awful effect.

Image (above): A print by Robert Chambers illustrating his book The King in Yellow. Credit: New York Public Library/Art and Architecture Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs.

Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘The Masque of the Red Death, with its decadent masquerade and spreading plague, was surely in Chambers’ mind when he wrote this. It’s chilling stuff, made all the more mysterious because the reader is left to fit the more prosaic tales in the volume into the larger themes of contact with a mighty force that can destroy the intellect. Not all the stories can be described as macabre but the feeling of strangeness persists, one that influenced H. P. Lovecraft and numerous later writers from James Blish, who set about writing a text for the mysterious play, to Raymond Chandler, who wrote a story of the same title using a narrator familiar with Chambers’ work.

Snaring the Mind in Language

But back to the extraterrestrial question, and the idea that contact may involve a deeply imperfect understanding of alien ideas that could be so powerful as to overwhelm our minds. What is it that could disrupt a human intellect? Michael Chorost talks about Shannon entropy as a way of working out the complexity of a message. That has me thinking about a Stephen Baxter story called “Turing’s Apples,” in which a signal has been received from the Eagle Nebula. We often think of such a signal being made as simple as possible so the beings behind it can communicate, but would they necessarily be communicating with us? What if we don’t get something simple, like a string of prime numbers, but an intercepted message intended for minds greater than our own?

In Baxter’s story, a SETI team has six years’ worth of data to work with. The signal technique is similar to terrestrial wavelength division multiplexing, with the signal divided into sections each roughly a kilohertz wide. Information theory says it is far more than just noise, but it defeats analysis. One character describes it as ‘More like a garden growing on fast-forward than any human data stream.’ The team has applied Shannon entropy analysis, which looks for relationships between signal elements. The method is straightforward:

You work out conditional probabilities: Given pairs of elements, how likely is it that you’ll see U following Q? Then you go on to higher-order ‘entropy levels,’ in the jargon, starting with triples: How likely is it to find G following I and N?

We can use mathematics, in other words, to work out the complexity of a language even if we can’t understand the language itself. That makes it possible to peg the languages dolphins use at third or fourth-order entropy, whereas human language gets up to about nine. In Baxter’s story, the mind-boggling SETI message weighs in with an entropy level around order thirty.

“It is information, but much more complex than any human language. It might be like English sentences with a fantastically convoluted structure — triple or quadruple negatives, overlapping clauses, tense changes.” He grinned. “Or triple entendres. Or quadruples.”

“They’re smarter than us.”

“Oh, yes. And this is proof, if we needed it, that the message isn’t meant specifically for us…. [T]he Eaglets are a new category of being for us. This isn’t like the Incas meeting the Spaniards, a mere technological gap. They had a basic humanity in common. We may find the gap between us and the Eaglets is forever unbridgeable…”

Chorost mentions Robert Sawyer’s WWW: Wake as containing a good discussion of Shannon entropy, which is why I’ve just acquired a copy. Meanwhile, the idea of a SETI message being so layered with meaning that we couldn’t possibly understand it does indeed put the chill down the spine that Chorost talks about, the same chill that Robert Chambers so effectively summons up in The King in Yellow, where language can suggest complexities that entangle the mind until merely human intellect overloads.

This interesting essay reminded me of two of Poul Anderson’s works: the novel called STARFARERS (1998) and the short story titled “The Martyr” (1960). In STARFARERS we see how non human rational beings called the Tahirians found human ideas (and humanity itself) so strange and disturbing that many Tahirians decided mankind was literally mad, insane. And “The Martyr” is a very chilling story by Anderson describing what resulted from humanity making contact with an alien race which was not merely more intelligent than mankind but genuinely BETTER than us. I will not mention the conclusion of “The Martyr” because to do so would be a spoiler.

I wonder if Monty Python could’ve had The King in Yellow in mind when they wrote the “Funniest Joke in the World” sketch. It’s a similar principle — a joke so funny that anyone who hears it dies laughing.

I think everyone is worrying too much. Look on the incomprehensible as an opportunity, not as a reason to avoid it.

As no doubt others will mention – “His Master’s Voice” by Stanislaw Lem, about receiving a complex, but ultimately unintelligible message from space. A superb piece of SF.

I should also mention “Our Friends from Frolix 8”, by P K Dick, in which advanced earth mathematics is used to drive alien invaders insane.

Also Hoyle’s “The Black Cloud” in which the humans trying to absorb the knowledge of the cloud die, a idea that has a long history.

Perhaps we need to bridge that “uncanny valley” of strangeness, not with individual human minds, but with groups of minds each understanding a small piece, but being able to assemble/understand the whole at the group (e.g. institutional) level, much like large software projects?

Food for thought. It is known that humans can only hold a very limited number of thoughts in working memory at the same time, approximately 2 per hemisphere. This suggests that very complex ideas cannot be understood at the holistic level unless they can be suitably chunked. Suppose we cannot chunk them? Then we will forever be in the situation of Chorost’s view of his understanding of Godel’s incompleteness theorem. We can understand pieces, we can traverse the set of of related ideas, but we can never comprehend it in totality.

There’s a bit in “His Master’s Voice” about a caveman who discovers a library and thinks he’s found a really great source of fuel for his campfire. Since he has no concept at all of writing he has no way of even beginning to understand the actual purpose of books. And of course the caveman (however ignorant) is nevertheless a human being. I suspect that humans in would be in a much worse position if we ever encountered a truly alien technology.

In a similar vein, dealing with language- or information-as-weapon, I would recommend “Babel 17” by Samuel R. Delany, and “Snow Crash” by Neal Stephenson.

Another example of an interesting and inscrutable hard-sf alien intelligence are the Pattern Jugglers from the “Revelation Space” series by Alastair Reynolds.

Messages beyond our level needn’t drive us nuts or, once familiar, provoke undue anxiety. Dogs can live comfortably with people, whom they can never wholly understand.

In our case we will be motivated to learn to increase our intelligence.

Thanks Piers Anthony. I for one am now finally comfortable relaxing knowing that I’m quite safe from going mad from alien messages. That said I’m in the camp that if alien intelligences exist that even with math being a fundamental aspect of the universe we’d likely not be able to understand them. I’m assuming intercept of their private messages vs detection of a purposeful contact beacon which is increasingly unlikely given search results for such.

Paul, you’ve already exceeded my understanding with what you wrote

above!

If aliens are so smart then they will be smart enough to know what we can and cannot understand. Therefore, if they wish to communicate to us, they will do so at our level.

Chorost: “It echoes Godel’s Theorem, which proves that it, the theorem itself, is unprovable.”

This is incorrect. There’s a nice and concise summary of the theorem on Wikipedia so no need to repeat it here.

—

On the subject of these books Paul is listing here most recently, I’m surprised that so many are familiar to me: Roadside Picnic; His Master’s Voice; The King in Yellow, etc. FYI, Chambers was also an early sci-fi writer, and some of his works are available on Project Gutenberg. Just be aware that it’s a bit dated (though pretty good for the time) and his open racism often shows up in his stories.

Agree with Ron S, Chorost statement about Gödel’s incompleteness theorems is incorrect.

It’s not a super easy read but the Wikipedia article is a correct summary:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gödel’s_incompleteness_theorems

(Godel in fact went insane toward the end of his life.)

Uh … Gödel had mental problems all his life , his works were not the cause of that.

Besides people like Bertrand Russell , Hilbert, Carnap … eventually hundreds of other mathematical logicians who came to understand the proof did not go crackers over it.

Paul, thanks again for yet another thought provoking piece. ‘The capable mind’ an entity that comes about on Earth resulting from our own endeavours but essentially alien to our species, is the theme of a novel that I have been working on for some time. My greatest problem in completing the book is my own limited intelligence, an inability to do such an entity justice. Ironic really.

I also read Roadside Picnic (finished it today) after Paul mentioned it here. Quite a read. Thanks, Paul.

I think any ET contact we have will be with civilizations that have gone through their technological singularity – as will we have by the time it happens.

One of my favorite comics come to my mind, “The Cantor Madness”:

http://abstrusegoose.com/65

With the very nice documentary “Dangerous Knowledge” posted below there. If you enjoy physics or mathematics, you might enjoy this (the other comics at Abstruse Goose are good too).

Otherwise, that’s the best I can contribute with my average IQ … :-)

In science fiction, of course, the problem is that an intellect much greater than our own is literally unimaginable. Not impossible, mind you, nor even improbable. Just “unimaginable,” in the sense that by definition we cannot imagine the details.

Ususally, science-fiction writers get around this by placing the average of the superhuman species somewhere around the range of human genius to supergenius (around the writer’s level), and then stipulate that the genius and supergenius level of this species is beyond our comprehension. Then the human protagonist (who is a genius to supergenius human) interacts with the “average” alien and is awed by the alien’s intellect being superior to his own: if he ever meets one of the really smart aliens, he is even more impressed.

A good example of this is Poul Anderson’s “Second Chance,” which is based on the assumption of an alien race very similar to humanity which never climbed out of the Late Paleolithic, thus never developed the crutch of civilization, and thus continued to intellectually evolve. By the time human starfarers find them, the Jorillians are so brilliant that mere stimulus-diffusion from casual conversation with the humans is enough to trigger not only a Neolithic revolution but also catapult them into the Iron Age, and it is obvious that even if the starfarers leave and never return, the aliens will develop starflight on their own within a matter of at most a few centuries.

The humans are undestandably frightened at the implications of having to compete with a new super-race, but horrified at the genocide which would be necessary to avoid such an event. In the end, they come up with the best possible solution for both races …

It’s a great story, which deserves to be read and re-read.

Ideas do have mighty power. And there is no doubt that our ideas are not the most powerful in the galaxy. So, yes, I would tend to agree that humans could be ‘jerked around’ by alien ideas intentionally or unintentionally. We could be trapped like a school of fish chasing bait into a factory trawler. I believe Earth is like a coral reef in the Pacific Ocean and we humans are like the local school of fish. But there are much greater reefs and fishes out there in the deep. And totally alien beings called fishermen.

There is a precedent for having ideas cause harm to humans. After reading the book “The Sorrows of Young Werther” by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, a number of young people committed suicide coping the book. Incomprehensibility cannot cause such a thing. Rather, an intimate emmotional connection is required.

Are those comment by Ron S and A. A. Jackson trying to show that the human mind can only remain sane after comprehending Godel’s theorem if it can no longer understand English and maths simultaneously!

Here is the problematic passage “It echoes Godel’s Theorem, which proves that it, the theorem itself, is unprovable. (I’m oversimplifying here.)”

Note how the first use of the word Theorem starts with a capital, and the second does not, showing that its second usage was meant in a more general sense. Thereafter he felt that his précis had still left such a misleading impression that he had to specify that it was an oversimplification.

I put it to you both, that if you knew nothing other than this about Godel’s Theorem, you would suspect that it undermined the theorem as a central basis for a mathematical system, but didn’t destroy it.

Now isn’t that close enough to the truth in the context of what is possible within a brief essay written in English?

The WMAP told us that the matter and energies we (sort of) understand are 4% of the universe. The default assumption is the fraction of the universe we do know is the “important” part – were the complexity lies. The rest is assumed to be perhaps a bland field and a boring particle, the scaffolding of our reality. The truly unimaginable is that baryonic matter and our four fundamental forces are merely a small section in a cosmic symphony forever beyond our ken.

If human languages normally reach ninth-level entropy, how do the works of James Joyce compare with that?

It would be truly entertaining to see Finnegan’s Wake run through such an analysis…

Rob, how can you honestly ascribe all those things you claim I say from just a few words that I wrote? We’ve been here before. Stop it!

I am pretty sure that once you understand ow that “entropy level” works, you can construct a nonsensical signal that would register at any desired level. To ascribe to it some fundamental measure of how “smart” the originator is is, frankly, absurd.

Sorry Ron, but what other way does Michael Chorost have of conveying the shock and awe that Godel’s Theorem impacted on much of the high IQ mathematical community?

@Rob

For one thing , the ‘shock and awe’ didn’t last very long. Gödel’s proofs came to be accepted , embraced and even extended.

Missing here is how the study of Gödel contributed to the still incomplete science of computation and AI.

See this month’s Scientific American, “Machines of the Infinite”, by John Pavlus, page 66.

A. A. Jackson, I wonder if “shock and awe” can only last so long before we really would all go mad.

Because of something you wrote months earlier, I am convinced that we both discovered special relativity directly from our own minds as school kids, after having been fed the seemingly incredible line “it all can be worked out by assuming that the speed of light measures the same in all inertial reference frames”. If so I would like to try the following on you.

Do you remember how truly awesome the discovery was when it all worked out? And do you remember your mind repeatedly rebelling and telling you that this is not the way the world really is even though you knew it was? And finally did you eventually stop trying to see the world in this new correct way and replace it with the idea that moving from one frame to the other transformed the real world to a new one – thus reinstating the Euclidian versian? I found such a change natural occurred for me as if it was to “preserve my sanity”

Also, thanks (I think) for that reference to Scientific American. I have occasionally found that that Journal gives just enough correct information to allow one to mislead oneself if the subject is extremely complex – but it is always a good place to start. I assume that the reason for you reference is that it a likely source of future “shock and awe” and so well worth investigating – if so I am grateful.

I had previously heard that there was some sort of connection between the halting problem and Godels theorem, and have frequently seen it mentioned as a problem to true intelligence. Unfortunately the second claim seems to often appear in the context of the problem of an entity fully understanding itself. Often people who mention it assume that realising you exist is somehow equivalent to fully understanding how a mind works, yet it appeared in this context so frequently that I wondered if this problem had depths that I had missed.