Centauri Dreams readers will remember Adam Frank’s recent op-ed Alone in the Void in the New York Times arguing that given the difficulty involved in traveling to the stars, humans had better get used to living on and improving this planet. ‘We will have no other choice,’ wrote Frank. ‘There will be nowhere else to go for a very long time.’ I responded to Frank’s essay in Defending the Interstellar Vision, to which Frank replied on his NPR blog.

Dr. Frank is an astrophysicist at the University of Rochester and author of the highly regarded About Time: Cosmology and Culture at the Twilight of the Big Bang (Free Press, 2011), a study of our changing conception of time that is now nearing the top of my reading stack. In his short NPR post, he makes a compelling point:

Even if we could get a starship up to 10% of light speed (which would be an epoch-making achievement) then the round trip to the nearest known star with a planet would still take 300 years (it’s Gliese 876d for all you exoplanet fans). It’s hard to imagine a culture driving significant changes in a significant fraction of humanity based on three-century long shipping delays! As much as I support moving forward in interstellar research, I can’t escape the conclusion that the theater of our future — for at least a few thousand years — will be here in the solar system. Not forever, perhaps, but millennia at least. And that is a long, long time.

On balance, what we are really disagreeing about is time, my own view being that interstellar flight may be a matter of several centuries away, while Frank takes a longer view. In any case, it’s interesting to speculate on what a society would look like if that 10 percent of lightspeed turned out to be attainable but remained more or less a maximum for space travel. We’ll doubtless find closer worlds than those around Gl 876 (even now the evidence for at least one planet around Epsilon Eridani seems strong, and we’ll see about Alpha Centauri). But a nearby world around Alpha Centauri B is still forty-plus years away at 10 percent of c.

Making Starflight Too Easy

From a cultural perspective, the discussion of interstellar flight has suffered from extremes. I think about something Geoff Landis once told me while he, Marc Millis and I were having lunch at an Indian restaurant near Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. We had come over from GRC after I interviewed the two there and we spent an enjoyable meal talking lightsails and Bussard ramjets and science fiction. A skilled science fiction writer himself, Landis felt that the genre hadn’t always been kind to the serious study of interstellar topics. I quoted him on this in my Centauri Dreams book:

“Science fiction has made work on interstellar flight harder to sell because in the stories, it’s always so easy… Somebody comes up with a breakthrough and you can make interstellar ships that are just like passenger liners. In a way, that spoiled people, because they don’t understand how much work is going to be involved in traveling to the stars. It’s going to be hard. And it’s going to take a long time.”

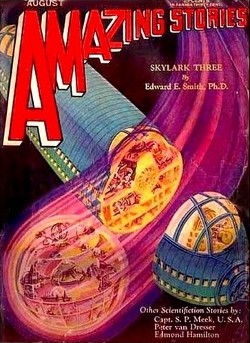

In Astounding Wonder (Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), John Cheng’s superb study of science fiction in the era between World War I and II, the author introduces Hugo Gernsback’s strategy of mingling science fact with fiction as a way into wonders that went beyond conventional physics. A case in point was Edward E. Smith’s ‘Skylark of Space’ series, published in Gernsback’s Amazing Stories in three installments in 1928. The tale, soon followed by popular sequels like ‘Skylark Three’ and ‘The Skylark of Valeron,’ went well beyond the science fiction of the period in its scale, invoking fast interstellar travel and a coming galactic civilization. Star travel mingled with romance and adventure to form ‘space opera.’

Image: The August, 1930 cover of Amazing Stories, containing the opening installment of Edward E. Smith’s ‘Skylark Three.’

Here we can see Landis’ point at work, just as we can see it on the bridge of the Enterprise in the Star Trek franchise. Gernsback wanted to keep science in the forefront but he accepted a vehicle — the starship — that defied all understanding of physics at the time. To do this, Skylark author Smith had to come up with an explanation for how his ships flew, and Gernsback’s readers critiqued it even though the device in question was pure fantasy.

Cheng explains:

…Smith provided a detailed discussion in his original story about the ‘intra-atomic energy’ within copper that powered the Skylark. Nonetheless attempts at more contemporary or realistic extrapolations of science were not distinctive features of his narratives. Their operatic sensibilities came from their adventure, the immense scale of their universe, and their moral and ethical consideration, drawing on their scope and perspective, of universal value. In the broader context of achieving universal civilization throughout the galaxy, full knowledge of the details of Einstein’s special theory of relativity might have seemed relatively unimportant. Readers, however, criticized Smith’s stories for their improper science or lack of scientific consideration in purely imagined devices, however small, but not for their grandiose social extrapolations.

The Starship as Plot Device

If Smith’s science didn’t stand up, readers like future science fiction critic P. Schuyler Miller (who explained the Lorentz-Fitzgerald equations in Amazing‘s letter column as a way of critiquing Smith) agreed that the tale was a thundering good read. In the same way, James T. Kirk and his descendants gave television viewers a feel for interstellar flight at warp speed, even though many of those enjoying the ride believed that such journeys could be nothing more than plot devices. It was only in the mid-20th Century, and really not until the 1960s, that a case began to be made that actual interstellar flight might be something more than a fantasy.

Of course, the kind of travel the early interstellar pioneers were talking about was nothing like Smith’s or Gene Roddenberry’s. I think Landis’ point stands up well — the reflex is to dismiss interstellar travel because our cultural representations of it have made it look absurdly easy. We’ve now learned that it is possible in principle to send a payload to another star within a human lifetime, but we also see that such journeys would take huge amounts of power and decades of time. Adam Frank is surely right that a society making this kind of journey wouldn’t be working with a cohesive set of colonies with convenient re-supply, but with outposts of humans that would be completely self-sustaining, a new and deeply isolated branch of the human family.

It’s an open question whether our species will choose to make journeys at 10 percent of c, or whether we’ll find ways to ramp up the speed to shorten travel times. Another open question is whether, if we really do find that a low percentage of lightspeed is the best we can attain, humans rather than artificial intelligence — ‘artilects’ — would be the likely crew of such vessels. One thing that is happening in the public perception of interstellar flight, though, is that the gradually more visible study of these topics is opening peoples’ eyes to the possibilities, and the difficulties, of interstellar journeys. A science fictional movie treatment of just how challenging a journey at 10 percent of lightspeed would be is a project worth exploring.

I think this shows us how important hard Science Fiction is. It shows how society thinks of certain ‘memes’ or possibilities and eventually that meme either grows to a point that it can be realized or it grows into something else or eventually dies.

Paul, as always, thanks for the article. It occurred to me that I should look at sending something simple in the simplest possible way to a nearby star. So, I decided to send my coffee cup to the nearest star (0.1 kg) at a reasonable pace (10% c). I assumed that we would fire my coffee cup sized projectile using a magnetic cannon (no onboard fuel) and see what we get. The following are my calculations and assumptions:

Assumptions

– Acceleration G load: 100,000 g’s (I calculated a riffle bullet at 70,000 g’s)

– Energy Efficiency: 80%

– Price of Power: $0.12 per kwh (that is what we pay where I live)

– Travel Distance: 20 light years (I assume we will find something interesting within that distance)

Calculated Values

Travel Time: 200yrs (less acceleration time)

Cannon Size: 291,242 miles long (Now that’s a gun!)

Power: 1,879,763 megawatts for less than a minute

Power cost: $1,977,940

Building a 300,000 mile long cannon might be a bit of a problem but the real result in this analysis is that either we will be sending really small payloads or the power will need to be practically free. If you expand the payload up to a mere 110 tons the power cost would be $1,977 Trillion dollars. We have a ways to go on the stellar travel front.

However, I do think we are fairly close (50yrs) to being ready to go tromping around our local system in Spanish Galleon style.

YMMV, but I put almost all the Galactic Space Opera SF I read or watch in the same mental category of my occasional Sword and Sorcery yarn…just a fantasy. There is a single exception…the Orion’s Arm website http://www.orionsarm.com which alone makes my suspension of disbelief possible.

I’m pretty sure Smith was entirely aware the physics were bogus. He did, after all, refer to Skylark as “pseudo-science”, regarding only a few of his works as genuine “science” fiction.

Hopefully your proposed movie would have production qualities better than “The Starlost”.

I think one has to made a distinction here.

I have run across a lot of physical scientists and engineers who took their inspiration to go into science because of science fiction. (I got to reading SF because I had to wait too long between issues of the Colliers space flight series! I was an impatient adolescent.) Of course I discovered Robert Heinlein to cut my teeth on , as far as engineering physics goes I don’t remember Heinlein ever getting the science wrong. I also don’t remember Heinlein ever giving me the impression that interstellar flight was easy.

That goes for all those of my friends who became scientists and engineers , tho some went into the social sciences. Every one of them , read enough popular astronomy to know about distances and all knew enough elementary physics to know what that meant for d = v*t.

Now if we are speaking of the unsullied, well that’s a different matter. I know plenty of intelligent lay-people who do know that interstellar flight is confoundedly difficult. I know lots of others who don’t.

Hollywood could be the culprit.

That breaks two different way. Those that are as ignorant as dirt, and those do it right but don’t explain enough.

In the first class there seems , for a long time (maybe still), a group of film and tv writers who have no concept of the difference between interplanetary flight and interstellar flight.

I remember startling the customers in line with me at the supermarket, years and years ago. I had picked up a copy of TV Guide , Asimov , for while, wrote reviews of TV SF. He was reviewing the first episode of Lost in Space, (I have to do this from memory) ground control radioed Jupiter 2 asking where they are. Someone says something like “we just flew past Pluto and are coming up on Alpha Centauri”. Asimov could not resist that, he said that’s like being on a bus pulling into El Paso and having the driver announce “folks on your right we are arriving in El Paso and out your left window is Canton China.” I barked at one.

On the other hand one has Star Trek and Star Wars , well at least Roddenberry really did know better ,set the show in the 23rd century (lets go modulo on some go0fey stuff in later years) and with FTL. George Lucas jumped the whole thing, placing SW in possibly a parallel universe (“In a Galaxy far away sound the same to me), FTL again.

Even the recent Avatar , to my mind, seems to kind of ‘fluff’ over interstellar distances, cryogenic technology is a sound extrapolation, but something is off about relative between the Earth and destination that feels wrong.

Maybe that’s the rub, if it’s in the movies or TV , for the unsullied , it’s right around the corner!

Regarding nearby destinations, it looks like van de Kamp’s claims of giant planets around Barnard’s Star have finally been ruled out by radial velocity measurements, and the limits on planets in the habitable zone are in the range of a couple of Earth masses. (More massive planets in face-on orbits would still evade detection though.)

Choi et al. (2012) “Precise Doppler Monitoring of Barnard’s Star“

“… if we really do find that a low percentage of lightspeed is the best we can attain, humans rather than artificial intelligence — ‘artilects’ — would be the likely crew of such vessels.”

I think that this focus on propulsion is a red herring (unproductive distraction). I think a more fundamental need is to create a sustainable, closed ecology that can support a small society. Once you have that you can leave Earth, either in open space, with access to useful materials, or on a body’s surface. Add propulsion when it becomes available and the range of travel increases, but is in no way required.

Do this and we no longer have to utterly rely on such artilects, even simple ones such as Curiosity, though they will still be useful tools in many (most?) circumstances.

“… how challenging a journey at 10 percent of lightspeed would be is a project worth exploring.”

It sure would. It can be done, as many island societies have shown. It’s just that if things go badly wrong there may be no plan B, just extinction for this one island, though there can be many others that have better outcomes.

The initial claim of Adam Frank is contradictory. If we mentions we have a solar system for us own-which he does, that already would meant a revolutionary change for human life and survivability. Imagine countless settlements on Jovian and Saturn moons, isolated biospheres under crust of Ceres or Europa, or in the caves of Mars.

Secondly-even with 10% of light speed this opens us to worlds in radius of 10 light years which could be reached within 100 years. This is fine for two generational ships(initial crew and then their children) and in case of Alpha Centauri-a one generational crew-with those who started the journey quite possibly being able to live to its end.

Furthermore with advances in medicine and human lives, life expectancy of a hundred or so years doesn’t seem that far fetched and with already you can see people in their 70s still quite active.

The huge energy involved in pushing mass to 0.1c suggests that it is unlikely that a significant proportion of the extant human population would ever attempt star flight. Unless we get new physics that can circumvent the energy and time scales involved, I suspect only a tiny fraction of humanity will ever travel to the stars.

However, that doesn’t mean that humanity is trapped in the solar system. I think we may have to get past the idea that a physical human being will make the journey. To my mind this is analogous to trees wanting to travel – they cannot, but their seeds do. Seeding humans across the galaxy in tiny ships carrying just basic information and being able to create life at the target may be the best approach. There are a lot of reasonable objections to this approach, both technical and moral, but the advantage in energy requirements would be great and their would be no loss of life if the target planets were unsuitable for any reason, or the ships never found a target.

With tiny ships traveling at 0.1c, the galaxy would be seeded in a million years, and no doubt early seeded targets would be raising new civilizations well before the seeding program was complete.

Biologists will recognize this as an r-reproduction strategy, which seems wrong to humans as we practice the K strategy and thus tend to think in terms of nurturing our passengers in worldships with high survival rates.

Very interesting. The “space, the final frontier” metaphor has dominated interstellar travel narratives throughout the 20th century, which isn’t surprising given the cultural dominance of the United States during that period.

A better analogy might be to the gradual human migrations out of Africa which spawned diverse and far-flung populations largely separated from each other for tens of millenia.

Just for discussion, there was a show which I thought captured what type of space travel might be possible. The show “Defying Gravity” aired in the fall of 2009, but was cancelled almost immediately. It depicted a diverse group of people traveling on a grand tour of the solar system. It was more about the people and their conflicts with each other, the company sponsoring the expedition and government officials on the ground. Some critics called it “Grey’s Anatomy in space.” However, I believe that it depicted the type of space travel that would be possible in the near future(50-100) years hence. There was no discussion, at least that in remember, that dealt with trying to start colonies on any of the barely habitable planets. I just thought it was a decent representation of what it would take to make even such a small voyage. Other solar systems seemed a very long way away with the technology shown.

In my long list of complaints about the recent movie Avatar, the very first item is its getting to Alpha Centauri in only 6 years, with a huge mass of planet-side vehicles. All that in a ship with not a shred of shielding, with huge open bays advertising Cameron’s complete ignorance of the difficult phenomenon of air leakage. Starships will be designed like submarines, not ocean liners: no windows, no big open volumes; the main difference being that in a starship everybody’s as far back from the bow as possible.

In the quote from him which you give above, Adam Frank still seems to be thinking in terms of a “round trip”, i.e. the Apollo model of interstellar flight. But at the end of his blog posting he concludes: “Should we be sending emissaries (and colonists) to the stars. Yes! Just remember that those who leave won’t really be coming back.” Thus he states what for most of us is surely obvious.

The difference between him and Centauri Dreams is therefore simply one of timescale: will passenger ships go to the stars in a matter of a few centuries, or one of several millennia? The answer will depend upon technological, social, economic and political factors which are unpredictable. So clearly there is room here for a healthy diversity of opinion.

The more significant battle for hearts and minds, I would suggest, is between those who envisage a starfaring future, whether it be reached quickly or slowly, and those who envisage the decline and fall of the modern way of life, and a return to, at best low-tech village socialism, and at worst, barbarism.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

The essential development to enable interstellar travel is self-reproducing machinery. We need to decouple industrial infrastructure from human population, so as to enable it to grow exponentially for many doublings at a much higher rate than population. The way to do this is to develop machines which can, (if only in combination with each other) reproduce themselves from native resources in the solar system.

This should enable us to transition to a K2 civilization in a couple hundred years, by surrounding the sun with a shell of power converting machinery. At that point we’ll have the energy to manufacture ton lot quantities of antimatter, or project energy and mass beams across interstellar distances at power levels sufficient to propel manned ships to relativistic speeds.

Without such technology resources can only grow in proportion to human population, leaving us without the excess power needed for activities as insanely energy intensive as interstellar travel. Eventually trapped in a solar system barely able to support a population in the trillions at a subsistence level.

Energy is the big problem, and self-reproducing machinery is the answer to that. The rest is easy by comparison.

Goodness, there has been a lot a scientific backlash against Avatar here and elsewhere. Sure – the future might look very different than you expect, but I have seen only one thing where the proposition “they DEFINITELY got it wrong by our current understanding of science” has held under scrutiny…

Those floating mountains could only levitate to the extent they did by magnetism, and the minimum fields necessary to hold them in place would be strong enough to scramble the electrical impulses within a unshielded human brain.

Even here I could imagine skull implants/replacements could have fixed this problem (I could be wrong), and that the surgery for it was so routine, as not to merit any attention within the story line.

Highly suspicious, but not inconceivable is extreme convergent evolution of the native intelligence with us, including female appendages that look so astonishingly like the engorged version of mammary glands that humans display. In fact so much so that the first contact with humans seems to started a wave of fashion such that they dress like humans.

I love how so much of the storyline revolves around extrapolations that are now only at the fringes of real science. Who can forget the shock when you first saw that room temperature Meissner effect of the local rock and suddenly realised that interstellar trade might make sense after all in highly extreme circumstances. What about the shock of discovering that those who thought sentience a quantum effect turned out to be right, and that quantum entanglement works well over hundreds of kilometres.

Come on guys – the scientific grounding here is greater than any other SF film I can think of. Though I agree with Ron S, that the general public are in desperate need off understanding how it works, I disagree with any implication that the film needs to explain it rather than this being the responsibility of (and an opportunity for) the scientific community!

Self-replicating machinery would be subject to inevitable degradation or to avoid that-mutation. Any advanced species that has dealt with this problem(and looking at the galaxy-it perhaps did), might not look kindly on attempts to repeat creation of such swarms.

Anyway-as discussed before-the talk about trillions of humans, space colonies or empires is from our flawed perspective. Our descendants might not find such ideas to use space as interesting as the literal caveman thinking that Library of Alexandria is a great source of fuel for his fireplace.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t explore or even use space-but I don’t think the end result will be any interstellar state or mega-engineering project to fulfill needs of XX/XXI civilization.

Oops, it was A. A. Jackson not Ron S who made that comment that was of secondary concern in my previous post. Sorry

Let’s be cruel and nasty and fight back a bit. Let’s grab some of these stuck-on-Earth-forever proponents (the entire staff of the NY Times, for the last 50 years, for example; every liberal economist in existence; every conservative economist in existence). And let’s say:

“This is one small planet in a solar system with 7 other planets, dozens of moons, and thousands of minor planets. This is in a galaxy of several hundreds of billions of stars, in a universe with hundreds of billions of galaxies. You would ignore this, to enjoy the prospect of another billion years or so of existence on this one world — or until rising solar temperatures make the place uninhabitable. We have 7 billion people on this world, we have limited resources, we have ongoing conflicts over religion and culture and wealth and class. And this is what you would subject the human race to, from now until its extinction. Explain why.”

And to the conservatives, we might add the request: “Explain why a world without spaceflight will evolve toward limited government and evermore perfect freedom and affluence for all. In 50 million words or less.”

Having asked these questions, we might return to the Times and ask Dr. Frank and the editors to explain how beautifully societies with or without long ranged cultural perspectives have surmounted the challanges of time. Preferably in cuneiform, but 20th Century German would also work.

AA The Lost in Space pilot is even funnier than the Asimov review. The Jupiter 2 was knocked of course and was Leaving the Galaxy!

(ME TV is reruning it and ST on Sat nights) In fairness it was a kids show . In that era as a little kid I watched LIS and Bonanza not Star Trek and Gunsmoke.

Even more amazing is Hollywood thought we would be launching a maned nuclear powered interstellar spaceship with cryonic tubes,laser guns,an amazing robot in October of 1997.Roddenberry actually had one version of Star Trek in 1999

Paul:

Brett:

Well said!

The long journey times have another (psychological) effect that may always make large-scale support for interstellar travel (and in particular, support for paying for developing the very expensive necessary technologies) self-limiting: Few people would be interested in making one-way voyages to other planets in *this* solar system, much less to worlds around other stars where the latest “news” from Earth would be years or decades old. (Elon Musk wants to colonize Mars, but I suspect that he will attract fewer pioneers than he hopes for.) Also:

While I would love to visit the Moon or Mars for a time and then return home, I would *never* willingly choose to travel to another star, even aboard a relativistic starship that could achieve 99.9999999999% of the speed of light, simply because of the temporal dislocation I would experience on returning home (which, of course, would be greater for more distant stars). In addition:

I never understood Carl Sagan’s enthusiasm for relativistic interstellar travel because–except for journeys to the nearest stars–those *true astronauts* (kudos to Robert Forward for inventing that term!) would never again see their relatives and friends whom they left behind on Earth. To put the matter in personal terms, unless a faster-than-light drive (or its equivalent) existed that enabled round-trip interstellar trips to be made in less than a year or two (as measured on Earth), I would have zero interest in going–and I’m sure that nearly everyone else would also feel the same way.

In the news, it is being reported that a recent coronal mass ejections (CME) was recorded to have been ejected at about 3,200 miles/sec. If we could catch that with a sail and accelerate to those speeds then, by my calculations, we could send a craft to Alpha Centauri distances in about 256 years without needing us to provide internal or external propulsion!

I disagre with the milenia time for the first interstellar mission, but i’m pretty certain that it won’t happen before the 0.10 c speed is attainable, my guess for the first interstellar robotic mission lies in the first half of the next century, just because the advancement of technology seems still grows exponentionally.

In the time we archieved the 0.10 c speed that means the best we can do for improvements is 10x more speed, probably max 5x more for real practical use, so that means that’s the best we can do, so we can stop worrying about wait for next gen propulsion system and finally we can begin with the interstellar missions.

For me any interstellar mission WILL BE robotic, specially in the time IA become really more advanced that it can rivalize with what a human can do, and of course robots are much safer than humans. The only exception will be in the time we resolve to colonize a planet around another star, that will be the only case where we will send humans in a interstellar flight.

This scenario of sending humans to colonize another planet needs to be extremely well planed, these humans will be self-sustaining and will be another branch of humans race, they can even rivalize with another humans or even be dangerous depending on their new way to live and think. All instructions and proofs of existence of Earth and what they are doing there and how they can communicate with us, we need prepare them to be an aly and help each other.

Some thoughts:

1. Even if we achieve interstellar flight capability, moving significant numbers of people (millions and billions) off planet requires several orders of magnitude greater capability than even that. I would not expect us attaining that ability (if ever) for quite some time after just attaining the means to send a ship across interstellar distances. So earth will remain the primary center, hub, and stage for the majority of human history for a very long time into the future. So the challenges of living on and improving this planet will remain. Space travel and space colonization will not be the sole solution to earth-bound problems.

2. By the time we achieve interstellar colonization capability, the presence or absence of planets will likely not be an issue. On the assumption that debris belts will be universal around stars, that will be all that we will need. We will go to the Centauri stars regardless of whether or not they have planets.

3. With slow multigenerational ships with the required large crews, the launching political entity cannot expect to maintain political control over the ship for long. It will be a colony not from the point of arrival, but from the point of launch. And by the time it gets to several light-years distant, it will be a de facto independent state. That means that mission planners cannot expect to actually have any control over ultimate mission goals. If the actual crew/colonists aboard ship decide to change the plan half-way through, return to earth, or go somewhere else, there is no way they can be stopped. This may dampen political enthusiasm for launching such missions, and would mean that most likely the primary political and economic contribution to preparing the mission will have to come from the people who intend to go on the mission. Basically, we may end up seeing the first generational interstellar missions being launched as private ventures rather than public ones.

Just to put the power requirements in perspective: if we want to send a real ship sized object (110,000 tons) to a nearby star at a reasonable speed (10% of the speed of light) with a reasonably efficient process (50%) then we would be required to harness 0.0008% of the entire output of our star (3,007,620,000,000,000,000,000 watts). Or, convert 1,046,529 kg of matter into energy.

I’m afraid Brent is right, we will be required to convert our sun into a dedicated human power station to become a starfaring civilization. Well…I guess we better get to it.

If I had to give odds, my bet is that Adam Frank is very likely correct in that humans will be locked into the solar system for at least a thousand years.

Yes, maybe will will be sending probes or robotic craft on 300 year missions to the nearest stars this century. But for humanity, this is going to be our place. If we cannot break even 10% of light speed, then our galactic neighborhood is going to belong to our robotic offspring for the most part — assuming we do not destroy ourselves first or enter another era like the Dark Ages.

It is not a bad place actually; we have at least one other suitable planet that can be engineered to support life given enough effort and time.

Of course, I’m an optimist and the pessimism of Frank’s piece doesn’t sit well with me. This is why breakthrough propulsion science is what excites me. Yes, “Star Trek” type propulsion is what the public thinks is inevitable without understanding just how unlikely it is that humanity will be able to build such machines.

But in the long run, I think something like that is what we will need. People think of journeys that fit well within human lifetimes. A four year interstellar mission? Yes! A 10,000 year mission? Uh, no.

“Self-replicating machinery would be subject to inevitable degradation or to avoid that-mutation. Any advanced species that has dealt with this problem(and looking at the galaxy-it perhaps did), might not look kindly on attempts to repeat creation of such swarms.”

Error checking data is not a novel concept. And I see no evidence of other advanced species. Looks to me as though we may be the first in this galaxy, a scary position, but one with remarkable potential.

I think the simple fact is that life outside a natural biosphere requires a sufficient ratio of industrial infrastructure to people, that without such automation it will be infeasible save as a stunt. With it, OTOH, the solar system is our playground.

However, it is certainly the case that self reproducing machinery would have to be very carefully controlled, to avoid it’s replacing our sort of life. Then again, when you’re talking about space craft with engines capable of sterilizing planets from across a solar system if aimed wrong, very careful control is a given, no?

@ JJ Wentworth “I would have zero interest in going–and I’m sure that nearly everyone else would also feel the same way.”

Which only confirms that you, and probably most of humanity, are not colony material. Much of humanity doesn’t want to leave their home village/town/city. Most Californians, a relatively prosperous and mobile fraction of humanity have never even left the state, even for a trip to Las Vegas in Nevada. Only a small fraction of the population want to live away from their birthplace and have the wanderlust to travel and settle elsewhere, particularly if it means cutting all ties with home.

For me, the issue is how much physical comfort would I give up, not the relationships lost. A Martian colony would likely be very limited. But a few hundred years of building might make it an attractive location to live.

Suppose small groups of humans did settle earth like worlds and slowly transformed them into civilizations, each with their own characteristics that would be known back on earth. Given a catalog, I certainly would have little difficulty in choosing one for a one way trip. What I want is to avoid being given incorrect information about the destination. This is a theme covered by PK Dick (“come to the offworld colonies…”) and explored specifically in “The Unteleported Man”.

James Jason Wentworth-one way trips aren’t so scary for many people, you write:

“To put the matter in personal terms, unless a faster-than-light drive (or its equivalent) existed that enabled round-trip interstellar trips to be made in less than a year or two (as measured on Earth), I would have zero interest in going–and I’m sure that nearly everyone else would also feel the same way.”

I don’t, and would gladly volunteer on such at trip(of course that is a fantasy). I am sure I am not the only one. I think nobody dreams of sending millions to other planets, hundreds at most, and that is a stretch. In a population of 7 billion(perhaps 12 when we will have the means), you will easily find millions of similar view.

amphiox:

” So earth will remain the primary center, hub, and stage for the majority of human history for a very long time into the future”

Actually if we ever colonize our own system, places like Jupiter or Saturn are morel likely hubs as they have access to enormous energy sources(Io’s flux tube for example), mineral resources, hydrogen and each represents a mini-solar system of its own.

Brett Bellmore:

“And I see no evidence of other advanced species. Looks to me as though we may be the first in this galaxy, a scary position, but one with remarkable potential.”

We haven’t been looking very hard or long ;) Besides a conservative species might not want civilization that are millions of years behind it in development to be aware of existence of others, fearing that they won’t be able to develop on their own.

Or perhaps all advanced civs try eventually to create von Neumans and they get an unfriendly “warning” from their Oort Cloud ;)

Choices are endless. I think we need to wait for answers to the question if we are alone a century if not more. Massive telescopic searches for other life-bearing planets are just the start.

@Amphiox By the time we achieve interstellar colonization capability, the presence or absence of planets will likely not be an issue. On the assumption that debris belts will be universal around stars, that will be all that we will need. We will go to the Centauri stars regardless of whether or not they have planets.

So why go? We have a nice rubble pile in the solar system, and we can dismantle planets too, if necessary.

Underlying your comment seems to be the assumption that the solar system will already be heavily population with O’Neills, and that other suns will offer new lebensraum. That seems like a distant prospect.

Given how fast our electronics are developing, it seems far more likely that we will live in a “Matrix-like” world, or at least one with “holodeck” capabilities, that will provide all the experiences for the would be star colonizer, without the physical difficulties.

I am not clear what the compelling reason is for human starflight, apart from the various prospects of cosmic annihilation of humans in the solar system.

“I am not clear what the compelling reason is for human starflight, apart from the various prospects of cosmic annihilation of humans in the solar system.”

Scientific discovery-if we image a life bearing world, some people might prefer the option to study it first hand if it is possible.

Religious reasons-there are religious groups that promote endless expansion of humanity. Other religious groups might find attractive moving away from main human race(for various reasons).

Similarly radical or extreme political movements might find it attractive to move away to start their own communities.

I don’t envision a galactic colonization-the period where above events happen will probably eventually fade due to technological advancement or ennui-the only reason left being scientific exploration-but that can go without colonization.

“I am not clear what the compelling reason is for human starflight, apart from the various prospects of cosmic annihilation of humans in the solar system.”

In his paper in the classic worldships issue of JBIS, Anthony Martin makes the point that, as civilisation’s productive capacity grows, so it finds things to do with its new capabilities. He mentions the Egyptian pyramids and empire-building. Given continued industrial growth, at some point we will then need to run a starship programme in order that our growing productive capacity will not go to waste.

This is of course a systemic reason why starship-building may be expected, i.e. one which emerges from social dynamics, rather than a logical reason, emerging from rational argument. I see an interesting parallel with present-day spaceflight: there are many rational arguments for and against it, and people who work for it may promote one reason or another (beating the Soviets/capitalists, providing jobs, science, commerce, etc.), but the capability itself grows regardless.

Stephen

“So why go? We have a nice rubble pile in the solar system, and we can dismantle planets too, if necessary.”

I believe experience has shown that the primary motive for colonization isn’t lack of living space, it’s getting away from the people controlling the living space you’re already in. That will drive people into the outer solar system long before the inner is running out of room. If we never get interstellar travel, we’ll still comet hop across the galaxy in time.

Wojciech:

A baseless claim, and simply wrong.

Brett:

Amen to that!

“I am not clear what the compelling reason is for human starflight, apart from the various prospects of cosmic annihilation of humans in the solar system.”

That is a strange thing for Alex Tolley to write. Do all other humans he knows only show interest in eating, drinking, sleeping, reproducing, and trival entertainments or the economic structure that supports this? How low do you postulate the fraction of humanity that has any interest in acquiring new facts, pioneering, or just the want of being first in one significant category. Perhaps you think that this second category is made solely from the poor and powerless?

Alex Tolley wrote (in response to my posting):

@ JJ Wentworth “I would have zero interest in going–and I’m sure that nearly everyone else would also feel the same way.”

[Which only confirms that you, and probably most of humanity, are not colony material. Much of humanity doesn’t want to leave their home village/town/city. Most Californians, a relatively prosperous and mobile fraction of humanity have never even left the state, even for a trip to Las Vegas in Nevada. Only a small fraction of the population want to live away from their birthplace and have the wanderlust to travel and settle elsewhere, particularly if it means cutting all ties with home.]

Not quite, in my case. In 1997 I moved to Fairbanks, Alaska from Miami, Florida by my choice, and in the early 1970s my family was preparing to emigrate to Townsville, Queensland in Australia (my father changed his mind because my mother lost enthusiasm for it). My lack of interest in traveling to another world (in this or another star system) *to stay* is based not only on a desire to avoid breaking personal ties, but also on a distaste for the idea of spending my life in an artificial environment.

[For me, the issue is how much physical comfort would I give up, not the relationships lost. A Martian colony would likely be very limited. But a few hundred years of building might make it an attractive location to live.]

I’d love to visit even a spartan Moon or Mars base (not even a colony), but I wouldn’t care to move to even a fully-developed, large colony on any such world because I would always be living underground or under a dome. I love forested mountains, grassy meadows, and snowy fields that I can enjoy in person, without having to wear a pressure suit to go outside. If Mars could be terraformed to have such environments I might like to live there, but even if that is possible (an admittedly big “if”), it’s well beyond the horizon of my lifetime.

[Suppose small groups of humans did settle earth like worlds and slowly transformed them into civilizations, each with their own characteristics that would be known back on earth. Given a catalog, I certainly would have little difficulty in choosing one for a one way trip. What I want is to avoid being given incorrect information about the destination. This is a theme covered by PK Dick (“come to the offworld colonies…”) and explored specifically in “The Unteleported Man”.]

Indeed–I’ve seen examples of… “THAT wasn’t mentioned in the travel brochure!” :-) If such human-colonized exoplanets had Earth-like environments (either naturally or through terraforming) that would permit people and terran animals (I like the SF term “terran”–it sure beats “Earthling!”) to live there as we do here, I wouldn’t have any objections to living there, especially if others I know also wanted to move there. Also:

I support the development of interstellar space flight technology–I’m no “nay-sayer” regarding it. I just see that there are some non-technological barriers to human star travel for many people, including myself. While I’m sure that there are people who would gladly volunteer even for one-way “slow-boat cryosleep starships” if they were built, most people would not want to move to other worlds even in our own solar system because the environments in which they would live would be so un-Earth-like.

After listening to all the pros and cons of these arguments concerning the validity of interstellar travel and who pays for it I got to thinking that perhaps the most feasible way of doing this without worrying about government are nations bonding together in a common purpose to accomplish this I suggest that there is a better way to go.

Namely this: we seek to inveigle individuals who are wealthy (billionaires) who would be intrigued enough and perhaps altruistic enough to part with some of their money for research and development for these types of enterprises. Before everyone goes and suggest that I have fallen off the deep end, please remember that Bill Gates has voluntarily sunk some of his enormous holdings into the development of a malaria vaccine and regenerative nuclear fuels that can burn and produce more fissionable materials thus leading to a longer core life. It’s certainly true that there might be some personal gain in it for him but I suspect at this point in his life he’s not hurting for money so this may be the real deal.

Turning to the question of individuals who would make the voyage to a distant star system, the answer is definitively yes! Not speaking for myself but for others who are born adventurers and those who seek other types of existences and challenges that can arise. Even in this day and age there are individuals who are adrenaline junkies and they would be more than qualified to undertake such a astounding voyage. I’d be willing to bet serious money that you could find more volunteers who would be qualified then you would have slots to fill.

There has been a great deal of discussion about the motivation of humans to expand and colonize nearby star systems and the galaxy in general. There are a couple of things about humans that I don’t think will change regardless of how wealthy or artificially augmented or virtualized we become. We want what we can’t have, we want the truth and we can’t stand boredom. For these reasons there will always be a small contingent of our species (regardless whether we remain one species or fragment into many) that must go. These are the reasons that we have populated every environment on earth where we can get a meal. If we survive long enough, whether in 200 years or 2000, some will go. And, if they perish, more will follow them. Some are driven, some will always be driven.

@Rob Henry

I’m not discounting the people ho want to explore strange new worlds..etc. What I am saying is that this can be achieved by:

1. Create immersive VR worlds. Game platforms seem to work quite well today, so imagine the quality of a simulated world in 100 years. There must be an infinite number of variations, all with different skill levels…

2. Building worlds [O’Neills] in the solar system. Use whatever imagination you like to create and populate those worlds with exotic biology. There is a lot of space to occupy. O’Neill estimated that the boundary for solar powered colonies might be a few light days from the sun. Bear in mind that such a colony is effectively a world ship without the fuel and engines.

Contrast this with star flight. As JJ Wentworth notes, the rest of your life would be spent traveling in a large can with only your descendants experiencing the target world. We have no terrestrial equivalent of such long journeys, unless you count the biblical 40 years wandering the desert. Maybe we can avoid that with hibernation, so that only a few years need be experienced before landfall, but that is speculative. Even more speculative is some sort of mind uploading, storage and decanting into a body on arrival.

And after all this talk of finding a target world, we haven’t even discussed what worlds might be suitable. Would a “New Eden” populated with terrestrial analogs even be allowed to be colonized by humans? And for those who assume we just use the target star rubble piles to build new colonies/ships, why expend so much in resources to go to another star for the same material available in the solar system – it certainly won’t run out in a few hundred years?

The brute force methods of propelling humans with life support at fractional c don’t strike me as very realistic. My expectation is that we will find completely different approaches to starflight, and I would bet that humans as we currently think of ourselves, will not be part of that approach.

My thinking is that it will take quite a long time before sufficient population transfer between Earth and Jupiter to occur for Jupiter, despite its resource advantages, to take over as the historical center-stage.

Jupiter/Saturn might relatively quickly take over as a resource and industrial hub. It might even become a political hub not much after (sort of like when a nation transfers its capital to a new small city outside the traditional major population centers), but so long as the majority of the people still live on earth, the majority of human activity will have to be centered on earth.

My thinking is that we will get greedy, and want more. Once we get to the stage where rubble-pile mining is relatively easy and within the reach of private individuals or consortiums, someone, somewhere will get greedy and ambitious (or desperately need to run away from other people for any variety of reasons!) and try for the next star, and sooner or later, some of them will succeed.

If we get that far, it actually becomes comparatively “trivially” easier to launch a “Matrix” hub with virtual individuals stored within, to another star. Now there wouldn’t be any huge compelling reason to do so, but once making such hubs becomes trivial, then trivial, even non-sensical reasons will do, even someone or group deciding to do it on a flippant whim.

It really just comes down to a matter of timing. Logical/rational reasons would promote starship-building as a major undertaking, one in which a significant fraction of a civilization’s resources are utilized for specific, self-interest related gains. In this situation, it would happen relatively “early” in a civilization’s development trajectory.

For systemic reasons we are looking at a much later point where the civilization has advanced so much that star-ship building is just a minor byproduct of general activity that does not necessarily have to serve self-interest or rationality. Today millionaires buy yachts for little rational reason. With a sufficiently advanced civilization, their equivalents will be buying star-ships.

Mutation is probably unavoidable, but that’s not necessarily a show-stopper. It certainly didn’t stop the progeny of the first self-replicators on earth from covering the entire planet up to and including the very atmosphere itself. It just meant that the forms that finally completed the covering end up quite different from the forms that first started out.

It only takes a tiny minority to get colonization going, though. And if history is any guide, some will go not because they want to, but because they will have no other choice.

Amphiox, higher life on Earth is only possible because of evolution through natural selection, and that makes quite specific requirements on self replicating entities, notably there has to be a large pool of available mutations that still retain viability, and whose line can avoid the error catastrophe. Though it is natural that life conforms to these requirements, we would have to very carefully add them to a created self replicating entity, and only then could this *evolutionary* problem arise.

Alex Tolley, I agree that your argument stands well in the context of alternatives to startravel. It is the very poor match of these arguments to synchronising the mindset of all factions of high achieving humans into such groups that concerns me.

I think of the interstellar limitation in terms of acceleration instead of speed. If a ramscoop could scoop up enough interstellar matter to sustain a nice, comfortable 1g, it would reach 0.02c in a week.

http://williamhaloupek.hubpages.com/hub/Calculations-for-science-fiction-writers-Space-travel-with-constant-acceleration-nonrelativistic

“I am not clear what the compelling reason is for human starflight, apart from the various prospects of cosmic annihilation of humans in the solar system.”

Ummmm….. this is pretty much what Christopher Columbus would have been up against by 99% of the population when he declared that he pretty much wanted to sail off the edge of the Earth – he couldn’t even get his own monarch to sponsor the voyage!

I cannot for the life of me remember the name of the first person who scaled Everest (Sir Edmund Hillary maybe?), but upon being asked why he chose such a risky venture, I think he gave the basic answer for almost all human endeavour; “Because it is there.”

If NASA, and the “space race” never happened, sooner or later someone would have voyaged to the moon.

Given that interstellar destinations offer possibilities that remain a total mystery, I believe that in the long term, like most horizons they will present an irresistible challenge to people – we actually NEED things to wonder at, challenges to conquer – I suspect the current (hopefully short termed) malaise of negativity that humans suffer is happening due to a lack of challenges to be faced down!

….. and please! Don’t be overly critical of James Cameron’s Avatar – it is a pretty good film, it has some not too subtle messages about human ambition contained within it – but for goodness sake, he had the sense to leave the basic physics of his movie within the (outer) bounds of what we know – the Venture Star travels to Alpha Centauri below C, and whether you love, hate or have never heard of the designer, is based on some reasonably good near future science done by Charles Pellegrino (in fact the section on his website regarding the design of the Valkyrie is fairly comprehensive and well thought out).

Sure, it requires antimatter/matter reaction to make it work, however Robert Forward said many years ago that the only reason that seems so hard at the moment is because we are not pursuing it.

Electric light was incredibly hard for Edison, and impossible for others, but we have had it for over a hundred years now.

By definition, the very first self-replicating lifeform to appear through abiogenetic processes could not possibly have had “a large pool of available mutations that still retain viability”, as being the first, it would in fact have had NO mutations and no variability. All that variability appeared spontaneously through mutations in subsequent generations. Doubtless many early lineages did in fact suffer error catastrophes and died out, but it only takes one lineage to escape this fate for life to take off.

I see nothing “special” about the very first self-replicating molecule that gave rise to all subsequent life. It had no special mechanism for generating “safe” variation, no special protection from error catastrophe.

Thus I see no special reason why we would “have” to “very carefully” add such features to a self-replicating entity. If the first self-replicating molecule which could not possibly have had such advanced features (as such features, short of intelligent design, could only arise through many subsequent generations of evolution), then a self-replicating machine would also not need to have such features “designed in”. They will appear spontaneously, so long as the mutation rate is not so high as to obliterate the starting population completely with error catastrophe right away.

Doubtless many subsequent lineages of these replicating machines will fail and die out, but it would only take one to succeed to colonize a large swath of the galaxy.