The Magellanic Clouds, visible in the southern hemisphere, are two dwarf galaxies that orbit the Milky Way, a fact that has always captivated me. We see the galaxy from the inside, but I have always wondered what it would be like to see it from the perspective of the Magellanics. The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) is, after all, only 160,000 light years out, while the Small Magellanic (SMC), its companion cloud, is about 200,000 light years away. Add in the recently discovered Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical at 50,000 light years from the galactic core and you have three exotic venues from which to gain a visual perspective on the Milky Way, at least in the imagination.

We’re so used to thinking that our solar and galactic neighborhoods are utterly commonplace that it may come as a surprise to learn that the configuration of spiral galaxy and satellite galaxies that we see in the Milky Way is actually quite unusual. New work on this comes from Aaron Robotham (International Center for Radio Astronomy Research and University of St. Andrews), whose team looked for groups of galaxies in something like our own configuration. The data for this effort is drawn from the Galaxy and Mass Assembly project (GAMA), a spectroscopic survey of ~340,000 galaxies using the AAOmega spectrograph on the Anglo-Australian Telescope that builds on and is augmented by earlier spectroscopic efforts.

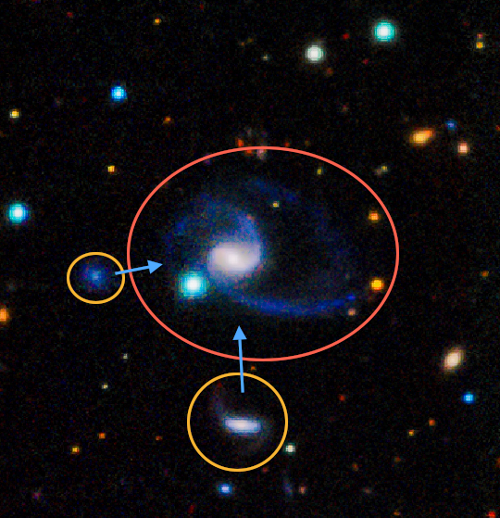

Image: This image shows one of the two ‘exact matches’ to the Milky Way system found in the survey. The larger galaxy, denoted GAMA202627, which is similar to the Milky Way clearly has two large companions off to the bottom left of the image. In this image bluer colours indicate hotter, younger, stars like many of those that are found in our galaxy. Image Credit: Dr Aaron Robotham, ICRAR/St Andrews using GAMA data.

The effort is interesting because we have never had a good understanding of how unusual the configuration of the Milky Way and its halo really is. The halo should contain the faintest known satellite galaxies because it is so close, and we should be able to study its characteristics to learn more about the galaxy’s formation history, knowledge which can then be extended to other galaxies. According to the paper on this work, simulations have trouble predicting the full distribution of satellite galaxies around the Milky Way halo, especially for the brightest of these, the Magellanics. Satellites in this configuration have been thought to be a rare occurrence.

The new work, presented at the International Astronomical Union General Assembly in Beijing, bears out this conclusion. Think of the halo as the spherical component surrounding the galaxy, which contrasts with the flat disk of the Milky Way. We’re on the cusp of major strides in our studies of galactic halos, because missions like the soon to be launched GAIA will let us measure the properties of 2 billion stars in the Local Group, including samples from all the member galaxies. For now, the Galaxy and Mass Assembly project has produced redshift data that allow Robotham and his colleagues to search for Milky Way Magellanic Cloud Analogs in the halos of galaxies with close companions much like our own.

The results bear out our simulations. The researchers found that only 3 percent of spiral galaxies like the Milky Way have satellite companions like the Magellanic Clouds. In the GAMA data, 14 galaxy systems were roughly similar to ours, but only two turned out to be a truly close match. Many galaxies have smaller galaxies in orbit around them, but few have satellites as large as the two Magellanic Clouds. About the closest matches, the paper has this to say:

Only two full analogues to the MW [Milky Way]-LMC-SMC system were found in GAMA, suggesting such a combination of late-type, close star-forming galaxies is quite rare: in GAMA only 0.4% (0.3%–1.1%) of MW mass galaxies have such a system (a 2.7? event). In terms of space density, we ?nd 1.1 × 10?5 Mpc?3 full analogues in GAMA (in a volume of 1.8 × 105 Mpc3). The best example found shares many qualitative characteristics with the MW system. The brightest pair galaxy has spiral features, as does the bigger minor companion. The minor companions are ?40 kpc in projected separation, so not in a close binary formation like the SMC and LMC.

Adds Robotham: “The galaxy we live in is perfectly typical, but the nearby Magellanic Clouds are a rare, and possibly short-lived, occurrence. We should enjoy them whilst we can, they’ll only be around for a few billion more years.”

The paper is Robotham et al., “Galaxy And Mass Assembly (GAMA): In Search of Milky-Way Magellanic Cloud Analogues,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 424, Issue 2 (2012), pp. 1448-1453 (preprint).

My “delicious” idea is that these satellite galaxies are merely “bigger globular clusters” composed of Type III star-civilizations that have moved their home stars to where the view of the parent galaxy is wondrous to see from their living rooms.

Note that the globular clusters have star types in them that are very old stable stars. If a Type III society was to arise, the chances are better for those civilizations on planets around long lived and stables stars.

I rest my case!

We see the galaxy from the inside, but I have always wondered what it would be like to see it from the perspective of the Magellanics.

Heinlein, we recall, vividly described all that back in 1958 in Have Space Suit — Will Travel.

I can see the clouds on any clear moonless night, and although easy to spot, they are less than dazzling. The LMC has more surface brightness, but it is certainly not any brighter than the Milky Way. So I suspect that a view of the Milky Way from one of the clouds would be similarly underwhelming. The Milky Way would have a huge angular diameter, but would be a rather ghostly spiral rather than a brilliant whirlpool of light.

I’m curious about what Robotham said about the Magellanics not lasting much longer than a few billion years.

Does this mean that they will eventually escape their Milky Way orbit?

Or that they will be attracted and fused as part of the Milky Way?

Or some other, more exotic process, like its old stars dying dimmer thus becoming untraceable in the visible spectrum?

Joy writes:

I suspect you’re right, Joy, and offer as evidence this post, which (in its first section) looks at Greg Laughlin’s thoughts on viewing a galaxy from the outside:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=12671

If this is correct, my imaginary view of the Milky Way becomes a poorer thing, alas…

I find it hard to believe that the galactic core that is obscured to us, would not be at least an order of magnitude brighter per area than the LMC, even if its outskirts (where we reside) is a little less bright. A lecturer of mine claimed that the Milky Way’s core would cast shadows in the night of planets in the Magellanic Clouds. Joy it may be a little ghostly but you omitted to factor in that it still held very high romantic potential.

Viewing the Sombrero Galaxy (Messier M104, see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sombrero_galaxy ) from the distance of the Magellanic clouds from the Milky Way would be a *real* treat–but alas, only immortal space & time walkers such as unicorns are privileged to enjoy such views… Also:

Just as there seems to be a rather “fuzzy” line of demarcation between planets and dwarf planets, could irregular satellite galaxies such as the Magellanic Clouds perhaps be very large globular clusters that were pulled out of their regular shapes long ago by gravitational and/or magnetic forces from closely-passing large galaxies?

An Infinitude of Tortoises said on August 24, 2012 at 14:58:

“We see the galaxy from the inside, but I have always wondered what it would be like to see it from the perspective of the Magellanics.

“Heinlein, we recall, vividly described all that back in 1958 in Have Space Suit — Will Travel.”

Nicely rendered in words, but the age of this text is revealed by the author referring to the galaxies as nebulae, back when most astronomers thought they were part of the Milky Way galaxy until the 1920s. Such a late date for such a major revelation still astounds me.

vruz,

From a talk I heard a few months ago on this topic, I recall hearing that the Magellanic Clouds are not bound by the Milky Way. That is, they approaching the Milky Way which will deflect their motion but they will escape. In other words, they are on hyperbolic orbits.

ljk

When Mr. Heinlein wrote those words galaxies external to the Milky Way was accepted fact (Hubble’s red shift and all that). However, the high school textbooks and encyclopedias of the time still referred to M31 as “the Great Nebula in Andromeda” due to its long usage. Having grown up in that time I still find myself occasionally thinking of M31 by that name.

Do we have any idea of the distance between the Clouds and the nearest, adjacent point in the Milky Way?

Thanks.

“The Magellanic Clouds will only be around for a few billion more years.”

But our descendents will arrive there in a few million years.

“I find it hard to believe that the galactic core that is obscured to us, would not be at least an order of magnitude brighter per area than the LMC… A lecturer of mine claimed that the Milky Way’s core would cast shadows in the night of planets in the Magellanic Clouds.”

No. The core would be brighter, yes, but probably not “an order of magnitude” brighter. But even if it /was/ a full order of magnitude, that would only increase its apparent luminosity by about -2.5. From Earth, the Milky Way is equivalent to fourth or fifth magnitude stars — it’s visible only on a clear night without any Moon or rival light sources around. So the core would be equivalent to perhaps second magnitude — clearly visible, but still far too dim to cast shadows.

Doug M.