Because I had my eyes dilated yesterday afternoon en route to learning whether I needed new reading glasses (I do), I found myself with blurry vision and, in the absence of the ability to read, plenty of time to think. Yesterday’s post examined a paper by a team led by Jack T. O’Malley-James (University of St Andrews, UK), addressing the question of how our planet will age, and specifically, how life will hang on at the single-cell level into the remote future. It’s interesting stuff because of its implications for what we may find around other stars and I pondered it all evening.

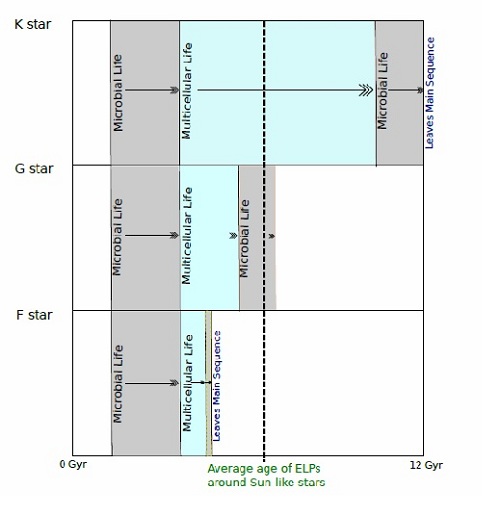

Have a look at one of the figures from the O’Malley-James paper, which shows the stages a habitable Earth-like planet (ELP) will pass through as it ages around main sequence stars. I also clip the caption directly from the paper.

Image: Time windows for complex and microbial life on Earth analogue planets orbiting Sun-like stars (F(7), G and K(1) stars) during their main sequence lifetimes. Assuming that the processes leading to multicellular life are the same as on Earth (i.e. 1 Gyr for life to emerge and 3 Gyr for multicellularity to evolve), the potential lifespans of a more complex, multicellular biosphere are estimated. Multicellular life was assumed able to persist until surface temperatures reach the moist greenhouse limit for an Earth analogue planet in the continuously habitable zone of the star-type in question. Microbial life is then assumed to dominate until either the maximum temperature for microbial life is exceeded, or until the star leaves the main sequence (whichever happens first). The average age of Earth-like planets was found by Lineweaver (2001) to be 6.4 +/– 0.9 Gyr based on estimates of the age distribution of terrestrial planets in the universe. This average age falls within microbial and uninhabitable stages for G and F type stars respectively, but falls within the multicellular life stage for K stars. Credit: Jack T. O’Malley-James.

Note the comparatively brief window for multicellular life in planets orbiting F-class stars when compared to a G-class star like our Sun, and note too that K-class stars (Alpha Centauri B is the nearest example) offer a much longer period of clement conditions for any planets in their habitable zone. The figure does not display M-class red dwarfs, but there the picture changes entirely because these stars can burn for trillions of years depending on their mass. If we do discover that life is possible on planets orbiting red dwarfs, then the time frame for intelligence to develop is proportionately extended.

With the universe now thought to be some 13.7 billion years old, is it possible that most intelligent species simply haven’t had time to appear on the scene? With up to 80 percent of the stars in our galaxy being red dwarfs, we may exist early in the overall picture of living intelligence, and most of it may evolve around stars far different than our own. Yesterday I talked about our gradual tightening of the number for eta-Earth (?Earth), the percentage of Sun-like stars with planets like ours in their habitable zone. What we are still in the dark about is eta-Intelligence (?Intelligence), the percentage of habitable zone planets with life that evolve intelligent species.

But back to F, G and K-class stars and what we do know. The O’Malley-James paper makes the significant point that G-class stars have a window for multicellular life that, based on the solitary example of our own planet, appears roughly the same length as the developmental period needed to produce it. And after the era of multicellular life, as the parent star swells toward red giant status, the era of microbial life returns for a still lengthy stretch, though shorter than the one that began it. Thus the reasonable statement “It is entirely possible that some future discoveries of habitable exoplanets will be planets that are nearing the end of their habitable lifetimes, i.e. with host stars nearing the end of their main sequence lifetimes.”

Without any knowledge of ?Intelligence, we can’t know what happens as the multicellular window begins to close. But if intelligence is not rare, then we can conceive of advanced civilizations taking the necessary steps to ensure their survival, either through migration to other star systems or massive engineering projects in space, perhaps remaining near the parent star. The kind of ‘interstellar archaeology’ championed by those who search for Dyson spheres and other massive constructs is an attempt to find projects like these, a form of SETI that is not reliant on the intent of a civilization to make contact and one that does not assume radio or optical beacons.

Which would be harder to detect: 1) the biosignature of single-celled life on a planet orbiting a dying star or 2) the infrared or visual signature of large-scale engineering near or around the same kind of star, as conducted by Kardashev Type II civilizations or higher?

I don’t have an easy answer for that because we know so little about what an advanced civilization might do to save itself, but it seems reasonable to pursue ‘interstellar archaeology’ with as much vigor as other forms of SETI. Certainly the boundaries of the discipline are expanding. Meanwhile, the O’Malley-James paper (citation in yesterday’s entry) points to the beginning of a much larger project that looks at extremophile biosignatures as a way of preparing us for the day when detailed information about terrestrial planetary atmospheres becomes available.

And the feeling persists: If M-class dwarfs are the wild card, what sort of hand has the universe dealt us? Are we, with our bright yellow sun that moves across the sky, the real outliers?

On earth like planets (ELPs) that have multi-cellular life: I think what we are moving toward being able to develop a chart of ELPs able to support multi-cellular life as a function of time in our galaxy out into the distant future. I assume this will look like an “S” curve for the early galactic development (which we are in now) and then sloping back down to zero in the far future. This will give us great insight into our place in the galaxy.

In order to make projections on the multi-cellular part of the equation, we will need to undertake surveys of ELPs for biomarkers of their developmental state. This could be a similar survey to the Kepler mission.

On the search for Kardashev type II architecture: This would be very instructive. If we are able to tell what has been done in the past and possibly what problems were encountered, we would be able to “fast-follow” in a much more effective fashion. For example: what kinds of stars make the best power sources, are there gaps in density of habitation and why, are there differences in architecture from area to area and why. If the average age of ELPs is ~2Gyrs older than us, our galaxy should already have been explored and settled.

If we are not able to find evidence of type II architecture, we will need to answer the questions “is it possible we are the first?” or “does intelligence tend to drive scale down instead of up?” or is there some other reasonable explanation. Let me say up front, I think we can come up with a better reason than all previous civilizations committed suicide.

We really know very little about the transition from bacterial life to eukaryotes and then to multi-cellularity. Is earth typical, i.e. that it takes a long time, or not? [Or is Earth’s example a relatively short time?] Thus the early period of microbial life depicted in the charts is based purely on a sample of one, and is very different from the estimates of the demise of multi-cellular life based on planetary conditions.

On the issue of astro-archeology. Let’s assume just a Kardeshev 1 civilization – i.e. us in a century or so. I assume that we could build a space based sunshade to reduce insolation, just for global warming. A stable version, perhaps a swarm, could be used for a hotter star. With sensitive instruments we should be able to detect the different spectral signature of a planet’s darkside and it’s shielded light side.

However, if intelligence is very rare (or we are unique), this may suffer from the same needle in a haystack problem as SETI. Looking for any life signature may be more likely to succeed.

I thought about that question a lot. To assume we are statistical outliers is cheating, i.e. not taking seriously the challenge this observation poses for our views on habitability and intelligence. The problem lies both in the high numbers of M and K dwarfs, and their longer lifetimes compared to G dwarfs. I see the following solutions to the problem (by themselves or in combination):

1) We are overestimating the habitability of M and K dwarfs. Therefore, a larger number of these stars will not necessarily shift the “observability” in their favor.

2) We are underestimating the effects of biospheres/habitats self-destructing at some point for internal or external reasons. Both Mars and Venus are thought to have been more habitable in the past. As planets cool, climate-self-stabilizing mechanisms like the ones driven by plate tectonics come to an end. It doesn’t help if the star remains life-friendly, if the planet doesn’t.

I’m no expert here, but wouldn’t a focus on detecting transiting planets around K-class stars possibly yield the greatest rewards in follow up research using spectrum analysis, etc?

An early K-star like Alpha Centauri B has the other possible advantage that the tides induced by the star on a habitable planet will have similar magnitude to those induced by the moon on Earth. This may have implications for the stability of the planet’s spin, etc.

@Greg Parris

1 – It’s possible we’re the first technological species in our galaxy. Somebody has to be first. There probably weren’t any stellar systems (or very few) with enough of the elements required for life until around 6-8BY ago, so if we’re not the first, we’re among the first.

2 – life may be very common, but intelligence may be extremely rare.

3 – it’s possible that civilizations are rare – not more than one or two existing concurrently in one galaxy; the nearest civilization may be 50-100KLY away on the other side of the galaxy.

4 – The civilization phase may be a short one and end either in self-destruction or evolution to a level where contact with lesser intelligence is about as interesting as conversing with ants.

5 – all of the above.

1 November 2012

Text & Images:

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2012-345

http://hubblesite.org/newscenter/archive/releases/2012/44/full/

http://www.ras.org.uk/news-and-press/219-news-2012/2183-asteroid-belts-of-just-the-right-size-are-friendly-to-life

ASTEROID BELTS OF JUST THE RIGHT SIZE ARE FRIENDLY TO LIFE

Solar systems with life-bearing planets may be rare if they are dependent on the presence of asteroid belts of just the right mass, according to a study by Rebecca Martin, a NASA Sagan Fellow from the University of Colorado in Boulder, and astronomer Mario Livio of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Md.

They suggest that the size and location of an asteroid belt, shaped by the evolution of the Sun’s protoplanetary disk and by the gravitational influence of a nearby giant Jupiter-like planet, may determine whether complex life will evolve on an Earth-like planet.

This might sound surprising because asteroids are considered a nuisance due to their potential to impact the Earth and trigger mass extinctions. But an emerging view proposes that asteroid collisions with planets may provide a boost to the birth and evolution of complex life.

[The rest of the article at the top link above.]

MNRAS paper, “On the formation and evolution of asteroid belts and their potential significance for life,” Rebecca G. Martin and Mario Livio [link may not be active till later]:

http://mnrasl.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2012/10/27/mnrasl.sls003.full

Another possibility is life migrating from planet to planet to follow the HZ. If the transition from prokaryotes to eukaryotes is potentially shorter than terrestrial experience, then the transfer of bacteria across planetary bodies via impact events could conceivably extend the period that multi-cellular life exists around a star.

Sometimes (such as when I read the article above) it seems that no one really believes in Darwin’s theory any more, but that we have reverted to Anaximander or Buffon’s version. With neo-Darwinism the idea of steady progress (such as that implied by scheduling the development of complex multicellular life after a couple of billion years) only makes sense within limited bounds where we hone pre-existing devises.

If we bring ourselves to the mindset of Modern Synthesis type evolution, then we may expect that the progress shown on Earth is EITHER

1) completely random at each major transition, and that we are thus very lucky to be here

OR

2) very rapid upon geological conditions allowing, and that Mars and Venus (given the reality of theories in which they both had surface water and high atmospheric oxygen content) most probably once hosted higher life forms if they were ever infected with lower ones.

In the first instance higher forms should appear any time after the end of heavy bombardment, but before “the moist greenhouse limit” with a probability distribution that looks a bit like an exponential curve, and in the second case the appearance should be accelerated for the case of the case of F stars, and retarded for K’s.

Under the previous post (Swansong Earth) I had just wanted to mention that the window of opportunity for complex life must surely become narrower toward the earlier stellar spectral types, until it becomes too narrow to develop at all somewhere around F7 or so, and voilà, there it is already in today’s post, again excellent and fascinating.

I love the figure of the time windows for the 3 stellar spectral types.

However, I think it would be even better if it had not consisted of 3 distinct types, but if instead there had been a continuous vertical axis of spectral types from about F7 to K1 (or stellar mass, or luminosity). Obviously, within spectral class G there is a huge difference between a G0 and a G9 star. In that case, the left microbial side would still be the same, but the right side boundary between multicellular and microbial life would be a continuous, sloping line, from bottom left to top right.

With regard to long-term planetary habitability, not only the stable main sequence life span of the star is relevant, but also the geological lifespan (plate tectonics) of the planet itself.

Paul, I think something went a bit wrong where you wrote the average age of Earth-like planets as found by Lineweaver (2001) as 6:40:9 Gyr. I think that should be 6.4 + / – 0.9 Gyr.

FrankH:

It is indeed possible. I do not like the “Somebody has to be first” argument, though. A better justification for being the first might be that the first invariably spread through the galaxy, precluding the independent development of others. Then, we have to be the first, simply because are is no second.

Note that that does not mean we are destined to become galactic Marauders. The overwhelming majority of planets with life will only have microbial life on them, and the chance that we will meet another intelligent species could be quite small. It is given, roughly, by the ratio of the time it takes to spread across the galaxy and the average interval between independent ETI emergences. Mostly, then, we will preclude the emergence of other ETI by occupying their real estate long before they exist, not by killing or enslaving them.

Of course, this scenario is only plausible if life is common. If etaLife itself is vanishingly small, we might be the only ones, period. First and last, with or without colonization. In this galaxy, or the entire universe. In fact, this might explain the enormous size of the universe. Anything smaller would have made our existence even more ridiculously unlikely….

Ronald writes:

Right you are, Ronald. I’ve corrected the text. Thanks.

“A better justification for being the first might be that the first invariably spread through the galaxy, precluding the independent development of others. Then, we have to be the first, simply because are is no second.”

Not really. They don’t have to spread, just as we don’t have to.

Also there can be a first civilization that spreads but imposes non-intervention on developing civilization, and stops others from contact, interference.

Additionally both time and distance of space go against the possibility of contact. If you are millions of light years apart but also millions of years apart in development, there won’t be any contact at all.

I checked ten well-known solar twins in the literature and found that the average age was 5.5 gy. This would indeed imply that most of them are in their 2nd microbial life stage.

So, the issue is not really that we would be the first, because everything is so young. Rather, most others are older and have already had their chance, they are past their complex life stage.

Most planetary systems around solar twins or solar analogs are at least a gy older than us. This just emphasizes Fermi.

Planets around the K-class star Alpha Centauri B, mentioned above, will not be able to take advantage of a lengthier habitable phase. Post main sequence evolution of Alpha Centauri A will destroy the habitability of the B system as well. Check out:

Beech, M., “The Far Distant Future of Alpha Centauri,” JBIS, vol. 64, p. 387-395, 2011.

I wonder about this scenario: A civilization develops. Their star (let’s call it S1) gets older and shows signs of expansion OR another star (S2) within 100-500 LY of their own is due to go nova or supernova. Being a Type II civilization, they decide to save themselves by moving away to another solar system (S3) far enough from S1 and/or S2. If I’d live around S3, I’d check all candidates for S1 by scanning any signs of civilization (radio signals? telltale life signs like O2 in the atmosphere? any other possible signs) around S1 and hope to detect them before they reach my home. If I should fail, they would probably never ask if they’re welcome – neither did Columbus, did he? Darwin’s theory is said to be one of the few biological theories we assume to KNOW are valid everywhere in the universe, so it would probably beat any polite asking. Now, if S3 is our Sun, does anyone know any S1-candidates within 1000 LY from here?

Wojciech:

This is only true if there is no spreading. If there is spreading, the vastness of time easily trumps the vastness of space. And if there are many ETI, you need to strengthen your prior statement from “They don’t have to spread” to “None of them can possibly spread”. One ETI that spreads is all it takes to get them everywhere.

Because of the vastness of time, “non-intervention on developing civilization” is not sufficient, either. It would have to be “non-intervention on any potentially habitable planet for all time”. My guess would be most ETI won’t want to be bothered with that.

“This is only true if there is no spreading”

As good as any other option, especially looking at our civilization, we didn’t colonize Antarctica or the Moon, although nothing stops us from doing so.

It would have to be “non-intervention on any potentially habitable planet for all time”. My guess would be most ETI won’t want to be bothered with that.

Why not, no telling what a million-year old Kardashev III civilization is willing and able to do-if it exists. Since even one loose cannon-civilization out of control could spread across whole galaxy contaminating all the unique possibilities, they could very well have infested whole galaxy with von Neumann machines keeping guard. All are present in all habitable system using technologies we don’t even comprehend.

Do not discount the possibility of a civilization spreading but then dying back before completely occupying the galaxy. New intelligences could then arise in the unexplored or abandoned space later.

And those new intelligences might have the advantage of having remnant technological artifacts to find to help bootstrap their development.

The prokaryote to eukaryote transition on earth most likely was precipitated by a rare endosymbiosis event.

The time lag could therefore be probabilistic. Since the confluence of both the endosymbiosis and the proper environmental conditions that provide a selective advantage for nascent eukaryotes over pre-existing prokaryotes must occur together before eukaryotic grade life can get a foothold. In such a scenario there is no hard lower or upper limit in time for eukaryotic life to emerge, but rather a probability smear wherein it is increasingly unlikely to have happened to earlier you go.

However we must also consider that it takes more than just that to make an eukaryote. A whole host of new genes and gene networks are required. In order for these genes to have any chance of evolving, even given the right environmental selection pressures, the necessary precursor genes must already be present for evolutionary processes (both mutation and selection) to work on. Evolution cannot and does not produce novel things from scratch. It always works on pre-existing precursors. Thus for the appearance of eukaryotic grade life to occur, there absolutely requires, beforehand, that a sufficient level of genetic diversity be attained in the prokaryotic precursor populations.

And that takes time. There should thus be an absolutely lower limit in time before which eukaryotic grade life cannot possibly evolve, because the necessary genetic precursors have not themselves had time to evolve, even given maximum evolutionary speeds of mutations, selection and generation times.

Once eukaryotic grade life is reached, it seems at least from earth’s example, that multicellularity is easily achieved with a relative minimum or truly new genetic innovation. However, multicellularity, at least on earth, first required the availability of far more abundant energy resources, which on earth took the form of the oxygenated atmosphere. And there really isn’t any other chemically plausible candidate other than Hydrogen reduction, which is about one third as energetic, than molecular oxygen.

And the oxygenation of earth’s atmosphere was not solely the result of the development of oxygenating photosynthesis, it also required stochastic geologic events that resulted in massive burial of carbon on very short geologic timescales. Such events may also be random in nature, and may not occur on other worlds.

Which is to say that molecular oxygen in the atmosphere should be considered a prime signature of not just life but of complex multicellular life.

Ponderer: A nova or supernova 100 ly away is not going to destroy anything, much less a planet. It is just too far away.

Columbus could easily have been killed with all his men had he been less friendly with the natives. I understand Cook was killed by the Hawaiians because of a dispute about a minor theft issue. A handful of ships could not possibly be equipped to fight an entire indigenous population, despite the technological advantage they may have had had. This could, of course, be different with aliens, but your example does not support that.

I wonder how a platoon of present day marines would fare against the native population of an undiscovered America, if they came with the intention to kill and conquer. Given an unlimited supply of equipment and ammunition, they might prevail. But without? For how long?

@amphiox

However, multicellularity, at least on earth, first required the availability of far more abundant energy resources, which on earth took the form of the oxygenated atmosphere.

Do we know that, or is it a post hoc assumption based on our terrestrial history? Is there a large barrier for bacteria to evolve multicellularity starting from biofilms, whether aerobic or anaerobic? Is there any inherent reason why microbial, circular genomes are incapable of supporting complex genetic pathways, even if size is a limitation. Obviously they didn’t, but could they? Perhaps a possible experiment in artificial selection to try?

Amphiox, I’m not as convinced as you that our planet would be without complex life had eukaryotes not evolved. It stands to reason that the larger possible cells, with more complex possible infrastructure, out competed bacteria for the niches available to complex life once they evolved, but I see little reason that multicellular bacteria might have got to higher life just as quickly had that completion been removed.

In our modern world myxobacteria have a nearly identical form, motility and way of living with the slime moulds. They have thrived despite the eukaryote competition, and the fact that their genomes are typically three times the size of other bacteria, indicates that this competition has been insufficient to confine these bacteria to the lower/simpler side of this niche.

Many cyanobacteria form at a second cell type called a heterocyst. These tend to be terminally differentiated, thus showing a higher grade of multicellularity than some animals such as sponges. Even today, when striped of eukaryote competition they form large distinctive complexes called stromatolites, as seen in Shark Bay, Australia. Just a couple of hundred million years before the base of the Cambrian, there was a much greater array of stromatolites that grew than today, many with a far greater array of cell types than seen now. I have even seen it suggested that their disappearance was the greatest mass extinction of all time. Anyhow, it has been traditional to think of the numerous different cell types as due to different species, but if this is not so, these extinct cyanobacteria could have displayed a much greater multicellular complexity than their eukaryote contemporaries.

Wojciech:

But that would mean the whole galaxy is occupied, which is the point I have been trying to make. It is neither time nor space keeping us from contact, because they (or their machines) are all around us and have been for a long time. It is only their curious decisions to 1) leave all of the potentially habitable planets undisturbed (so we can be here) and 2) keep hidden from us while we develop our technology. Not what I would expect, but, of course, you are right: there is no knowing what they might do. Note, though, that the first decision requires incredible resolve kept up for billions of years.

Amphiox: The time lag would be probabilistic only if there was one or at most very few major barriers preventing the development of multicellular life. I am not convinced that the development of Eukaryotes is such a uniquely rare event. There are plenty of other examples of endocytosis, and there are plenty of other candidates for rare events, to such an extent that the simpler assumption is that there are numerous barriers of similar size, which would make the progress of evolution much more predictable.

Eniac,

A Supernova 100 ly away would not blow the planet away, but the radiation would most probably harm life within a similar radius (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supernova#Effect_on_Earth). Of course, estimates on the range and the effects differ.

I agree with you that Columbus could easily have been killed, as well as a platoon of present day marines (sooner or later, they’d be out of ammo). However there are other scenarios as well: most Indians were killed by sicknesses brought in by the newcomers from Spain, since they had no natural immunity to protect them against the – for the Indians – new strains of bacteria.

Regardless of the outcome, I think it would be a good thing to consider the possibility of an unwanted outcome and prepare for such a scenario.

The question of whether there are currently any intelligent life forms living on other planets in this galaxy can’t be answered by postulation, because there are too many variables we either have no ability to set ranges on, or simply do not know about. Observations on various fronts are much needed if we are to take this question anywhere beyond the SWAG stage. That said, there is one thing that bothers me. Many of the people currently advocating strongly for humanity to expand into space speak of the need to “expand”: expand our resource base, expand our power generation capacity into space, expand humanity’s presence onto other world, both in this star system and in others as well. That drive to expand bases on the idea that if we can access something, we should automatically take it. So what sort of precident does that set if we do eventually encounter another intelligent life form? If their needs are dis-similar to ours, we might come to some sort of compromise, but if their needs are similar, do we just go ahead and take what we think we need? Columbus is an example of what happens in that case, with the “native” population being enslaved/wiped out tp make way for the “superior” group. Is that the future we should want for humanity?

alex wilson said on November 5, 2012 at 16:29:

“That drive to expand bases on the idea that if we can access something, we should automatically take it. So what sort of precident does that set if we do eventually encounter another intelligent life form? If their needs are dis-similar to ours, we might come to some sort of compromise, but if their needs are similar, do we just go ahead and take what we think we need?”

I have brought up this very important issue many times on this Web site. So far the consensus seems to be, if I get a response at all, a collective shoulder shrug and a “We’ll find out when we get there” or “That’s a problem for our distant children” attitude.

Of course those who think the highest life forms in the galaxy beyond Earth are pond scum often take the attitude that the Universe was clearly made for humanity and we can do with it as we please. Marshall Savage of The Millennial Project: Colonizing the Galaxy in Eight Easy Steps and his Living Universe Foundation cult are prime examples of this attitude, declaring that the galaxy is void of other organisms and it is our Manifest Destiny to colonize the Milky Way and eventually beyond.

Even more than the issues of what might happen between two alien technological intelligences that meet up one day, even if the Universe is empty of life, it is the height of absurdity and hubris that a collection of creatures which barely knew how to use the wheel just a few thousand years ago and hasn’t set a single literal foot on any world other than their Moon can presume that a place over 13.7 billion years old (and twice as wide in light years) with 77 septillion star systems (and no doubt much more than that) is theirs for the taking.

Time for a refresher from the famous Pale Blue Dot photo of Earth taken by Voyager 1 in 1990 from the edge of the Sol system. Just a few billion miles away and already our planet is a barely visible speck in the cosmic darkness – and the whole of the human race is not in sight at all:

http://www.bigskyastroclub.org/pale_blue_dot.html

I am not besmirching the noble and hopeful attitude that we can even seriously conceive of sending vessels into deep space. I am saying we should not presume to know what is out there based on so little evidence so far.

While I don’t think we have a Star Trek style galaxy, I would not be surprised if we come across beings who will not be humanoid but will share the traits of protecting their own against strangers. And we should also not be shocked if they have a similar attitude of The Universe Was Made Just for Us by Our Deity.

Just like when the Vikings met the Native Americans, our first encounter with an ETI probably will not be neat and clean nor by scientists or noble astronauts. There may not be an outbreak of violence, but confusion which could lead to problems is certainly possible.

Just as I have advocated with METI, we should be as careful as possible when venturing into that vast unknown, but it will happen one way or another thanks to human nature – and we should expect the same from other beings with inquisitive minds.

Ljk and alex wilson: wise words, I fully agree.

However, to add some nuance to that:

First of all, we are in no position, practically speaking and in any foreseeable future to consider the universe as ours for the taking, whether that is a good thing or not. Rather I think, it would be a good, more realistic and humble achievement if we finally manage to reach any other suitable planetary system, in order to allow our life and intelligence to survive, for no matter how the Fermi Paradox will eventually be answered, advanced intelligence must be a very rare occurrence in the universe and therefore well worth preserving. And becoming a multi-planetary species is probably one of the best ways to ensure our song-term survival.

Secondly, chances are greatest that the first suitable planets that we will find are either uninhabited but terraformable and/or inhabited by primitive micro-organisms only, as this post itself also suggests. This fact will significantly reduce the moral dilemmas of colonization.

Ronald, I am thinking very long term. If our interstellar endeavors turn into the equivalent of Apollo, then they will be virtually pointless. As the main character said in the 1936 film H. G. Wells’ Things to Come, it is “all the Universe – or nothing!” We either head out to the stars to stay, or just stay home and see how long our civilization and species can last confined to its solar system. Hopefully there will be enough of the right-thinking kind of people to make this happen for at least some of our species.

As for those alien microbes as the highest forms of life on other worlds, what if they are at the stage Earth was at two billion years ago? What if messing with them halts what could have been an intelligent species down the road? Imagine if ETI had affected our very distant ancestors in their effort to say they had the right to colonize Earth because the highest beings on the planet were algae and stromatolites.

If humanity’s starfaring children still feel the need to dwell on an actual planet, as opposed to roaming artificial worlds of their own making, I am sure there are plenty of uninhabited places in the Milky Way galaxy that can be transformed to their liking. I just hope the scenario found in Avatar remains science fiction.

Considering how little we have waded so far into the Cosmic Ocean as Carl Sagan once said, it would seem we will have negligible effect on the rest of the galaxy for ages. However, if you look at things on a cosmic time scale, we could be heading out there in a very short time. Not only do we have a responsibility to tread carefully and respectfully, we better not assume that no one else is around with similar intentions.

I still have the feeling that despite all our best intentions and noble words, the first humans to venture to the stars may be some kind of cult/political faction and their first encounter with truly alien beings may also be their last, with unknown repercussions on the rest of humanity.

ljk: again, very well spoken and again I agree with everything you say.

In your first paragraph you state exactly what I felt and meant to say: that, in order to allow our species, earthly life, intelligence and civiliation (and all its possible kinds of offspring) to survive really long-term or at least spread the risks significantly, we will have to colonize other solar/planetary systems.

There is almost no choice here, indeed, the stars/universe, or nothing.

And yes, a civilization that is able to go star-faring, is probably also able to terraform uninhabited suitable planets (as well as build artificial space colonies, to make everybody happy).

So, indeed, we should and could tread very carefully and with the utmost respect for any present lifeforms.

Your second paragraph poses a potentially very realistic dilemma: what if terrestrial planets with only ‘primitive’, i.e. single-celled/microbial (and maybe simple multi-celled colonies) appear to be common and perhaps even the only available nearby suitable planets?

If such a planet is in its second microbial stage, one may argue that it has already had its chances with regard to higher life and there is no real moral dilemma. But if it is still in its first microbial stage? I expect that, in case of limited availability of suitable planets (and a perceived human need for them instead of or in addition to space colonies) we would not hesitate very long, if our own survival and needs are at stake.

But, as mentioned in the post above, various studies indicate that the average solar analog is about 1 to 2 gy older than the sun and hence may be expected to be either clearly advanced in its multicellular/complex life stage, or already in its second microbial stage.

Somewhat off-topic, but interesting and related to the issue of average stellar age, is the recent article in ScienceDaily: ‘Star Formation Slumps to 1/30th of Its Peak’:

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/11/121106114141.htm

with journal reference,

which shows that new star formation in the universe is way past its peak (which was about 11 gy ago) and still declining sharply, and hence most stars in the universe are older stars.

Quote:

”

They find that the production of stars in the universe as a whole has been continuously declining over the last 11 billion years, being 30 times lower today than at its likely peak, 11 billion years ago.

(and) is now only 3% of what it used to be at the peak in star production.

If the measured decline continues, then no more than 5% more stars will form over the remaining history of the cosmos, even if we wait forever. The research suggests that we live in a universe dominated by old stars.

”

The good news is that our own Milky Way galaxy is relatively healthy and star-forming.

Paul, is this perhaps something for a separate post, also in view of intelligent life in the cosmos and Fermi?

@LJK:

Really? Would you advocate transform such a place, not knowing if not one day life might arise on it, without your inconsiderate interference? Where do you draw the boundary? Microbes – don’t disturb, no life – trample away?

Ronald and ljk, I like what you both said. I also think we should be ready not only to expand our domain to other worlds (in the very very long run for a single human life, but maybe tomorrow from the perspective of the human civilization) but also to be prepared if any other intelligent life form should try to do the same with our world. Contact? Exchange of knowledge? Peace and trade? I hold it to be possible but unlikely, as pessimistic as it may sound. We’ve just had too many “cowboys and indians” stories throughout all of the human history.

What do you think?

P.S. Concerning the decline in the star forming subject, I’ve found a prominent opposing opinion here, which I find more likely to be true:

http://scienceblogs.com/startswithabang/2012/11/07/every-galaxy-will-have-new-stars-for-trillions-of-years/

And this also just in:

3 more super-earths discovered around K2 star HD 40307, bringing the total to 6, of which one, the outermost, is in the habitable zone.

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/11/121108073927.htm

Eniac said on November 7, 2012 at 22:14:

“[@LJK: I am sure there are plenty of uninhabited places in the Milky Way galaxy that can be transformed to their liking.”

“Really? Would you advocate transform such a place, not knowing if not one day life might arise on it, without your inconsiderate interference? Where do you draw the boundary? Microbes – don’t disturb, no life – trample away?”

LJK replies:

I was thinking primarily of planetoids and comets, but also of course moons and planets where it is evident that nothing living has ever been there or will be. I am presuming if we can reach other star systems with probes we will also have highly sophisticated tools for searching for life.

Funny you bring this up as I had just posted elsewhere in this blog yesterday that we should think twice before messing with worlds with even microbes on them, on the chance that one day they could be the distant ancestors of intelligent beings.

That being said, if we are heck bent on colonizing, what will the limits be for not disturbing an alien world? Of course this will all be academic for us as I doubt our galaxy-spanning children will know what we ever said. Unless Paul starts archiving Centauri Dreams and scattering discs all over the Sol system.

Ponderer said on November 8, 2012 at 7:46:

“Ronald and ljk, I like what you both said. I also think we should be ready not only to expand our domain to other worlds (in the very very long run for a single human life, but maybe tomorrow from the perspective of the human civilization) but also to be prepared if any other intelligent life form should try to do the same with our world. Contact? Exchange of knowledge? Peace and trade? I hold it to be possible but unlikely, as pessimistic as it may sound. We’ve just had too many “cowboys and indians” stories throughout all of the human history.”

Not all contact between two different cultures in the past has been detrimental to the so-called less advanced/powerful society. The Romans borrowed quite a bit from the Greeks as just one example.

Unless an ETI is out to destroy us, I think contact with an advanced alien species is something humanity needs, especially getting across the idea that we need to get off this one rock and spread out into space.

ljk,

The Romans and the Greeks are, in my view, an interesting example. Yes, the Romans “borrowed” a lot from the Greeks, but the Romans also pursued and achieved the goal of ruling over the Greeks as well, didn’t they? And this as an example of Romans and Greeks having a relatively similar level of technology, and culture (compared to Columbus’ Spaniards vs. the Indians, not to mention any ETI vs Homo Sapiens). I think the bigger die differences in biology, technology, culture and the idea of moral, the greater the chance that Darwinism as an urge to prevail over the competitor will top the curiosity about the chances of trade or knowledge interchange. Any ETI “visitor” may likely be thousands or millions of years away (=ahead, assuming they are visiting us and not vice versa) from our development stage and thus see us as we see animals on Earth. Most probably a resource, not much more.

I’d be glad to be wrong on that, by the way…

How about your view? Do you think Darwinism is universal out there (presuming life exists somewhere else as well)?

Ponderer, I am afraid that that ‘prominent opposing opinion’ isn’t very scientifically founded.

Sure, most hydrogen gas in the universe has not been used for stars, and there are going to be new stars for many, many billions of years to come, but the star formation *rate* is declining steeply, because of the fact that most hydrogen gas within (most) galaxies has already been used up and the hydrogen gas in intergalactic space, where by far most of this gas is, will remain unavailable to galaxies and star formation.

I am not so sure. The internet is pretty well archived these days, with Google, the Wayback machine, and all sorts of projects trying to address that very problem. In my view, information technology will continue to progress even faster than our ability to acquire knowledge, and every word we write here will become history for the long haul. Obscure, maybe, but preserved and instantly accessible by search, nevertheless. And when our descendants reach for the stars, they will take it all with them. In their pockets, perhaps, on a 64 petabyte flashdrive….

As we define life, if the other creatures in the Universe have similarities to the natives of Earth, then yes there would probably have to be some form of Darwinian behavior in order for them to eat, reproduce, and do whatever else it takes to survive and pass on their DNA or their equivalent.

Please note, though, that Darwinian has long been thought of as a bloody battle for survival, where the weak are preyed upon by the strong and such. Biologists and those in related fields are now noting that altruism and cooperation is just as much a survival trait as dominating rivals for food and mates.

Discounting the more bizarre possibilities for a moment, I can imagine that the more intelligent and sophisticated a being is, the more likely they will avoid such barbaric tendencies as tribal warfare. A social group quickly learns that cooperation and mutual protection keeps things running relatively smoothly and intact or the risk literally falling apart.

Humanity has often cooperated as not if for no other reason than to live in more comfortable and less violent situations. Imagine what an ETI with higher technology and knowledge would strive for in this regard.

Here are some references on this subject of biological altruism:

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/altruism-biological/

http://www.wildlifeextra.com/go/world/darwin-evolution.html#cr

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2012/02/the-paradox-of-altruism/

A quote from the second linked article above:

“Any animal whatever, endowed with well marked social instincts, the parental and filial affections being here included, would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience, as soon as its intellectual power had become as well developed, or nearby as well developed, as in man.” – Charles Darwin, 1871. The descent of man and selection in relation to sex.

ljk,

Thanks for sharing your views on Darwinism and the links. I wish they’d help me come to a conclusion leading to altruism, but the best one I can currently come to is that there are both chances for selfishness and chances for altruism. The articles seem to report of altruism as a sort of “exception to the [selfish] behavior expected”. A pessimist could use this and proclaim selfishness to be the rule and altruism the exception. An optimist would say “the more advanced the species’ society is, the bigger the chance of altruism”. I assume we can say humans are the most advanced society on the Earth, and we have both: the wars and the hunger on the one side, and altruism on the other (both on international as well as on individual level, which is comforting).

Now, if any ETI would come here and display both, what might the outcome be?

P.S. I especially liked the story in one of your links about the chimp trying to help an injured bird by taking it into her arm, climbing up the tree and spreading the bird’s wings. Unfortunatelly for the little bird, the altruistic chimp was no veterinarian, and it apparently threw the bird off of the tree in an attempt to help it to fly, not understanding the nature of the bird’s injury.

Imagine a friendly alien trying to help humanity do whatever it assumed we should be doing :-))

@Ronald: As for the scientific foundation of the “prominent oposing opinion” I quoted above: it was written by a person who used to be an astronomy professor on one of the U.S. universities, author of the blog selected to be the “best scientific blog in the U.S.” (I believe in 2010, but I’m not so sure about the exact year), and many of his blog articles – including the one I quoted – are IMHO very well scientifically founded. Not only does what he writes make sense, he often backs it up by citing authors of scientific papers or simply plain common knowledge or facts from Wikipedia.

His portraits at the top of every blog article may be unconventional, but the content of his blog seems well explained and (more important) backed by observations.

So I’m just curious to learn how did you get the impression that the article mentioned in the link is “not very scientifically founded”?

Goodness Ponderer, I really do worry over statements like “A pessimist could use this and proclaim selfishness to be the rule and altruism the exception”.

For starters, its way too limited, and, to me, should be strengthened to “true altruism (as exemplified by anonymous donation towards non-related strangers) is ALWAYS excluded, and any example of its behaviour can be viewed as a perversion of evolutionary principles.”

If that seems way to bleak, it is because of what we left out. These same principles drive us to help others in all cases where even a small disproportionate advantage accrues to our particular genetic line. These forms of “limited altruism” are common, and the more socially sophisticated the species, the greater the potential for them to apply.

The most serious difference I have with you is your statement “wars and the hunger on the one side, and altruism on the other”. And oh to see ourselves as an ETI would, because war is the most extreme and obvious case of limited altruism displayed by humans. Here masses of individuals willingly lay down their lives for the good of their group, often in the face of absolutely no prospect for personal gain.

The lesson here is that these cases of “limited altruism” don’t always have to lead to the greater good of the global community as a whole, and consequently, lower levels of social behaviour in an ETI are not necessarily bad for the consequences of contact. Another example along these lines is that an ETI that has evolved from a predatory line has an evolutionary advantage for developing an ability to predict the actions of its prey. So carnivore stock ETI should have an evolutionary bias towards empathising with other species, but herbivore ETI’s would not.

I hate the way so many commentators oversimplify the problems to the absurd degree of reducing them to slogans, but then this is exactly the way we treat political situations, so I suppose that is the best than can possibly be expected from a bunch of humans from the softer sciences.

Ponderer, with all due respect, for you and for the man you refer to (his blog is indeed very nice in itself);

“but the content of his blog seems well explained and (more important) backed by observations”.

That I dare doubt, when I compare it with the article by Sobral at el. Also take notice of Sobral’s own comments on the blog you refer to.

Sobral et al.’s conclusions are based upon real and comprehensive observations of star formation in many galaxies of very different ages, in fact spanning almost the entire history of our universe. Their main observations and conclusions are that star formation has been steadily, continuously and strongly declining *at a universal scale*. This simply because the amount of hydrogen gas available for star formation within those galaxies has been steadily and sharply diminishing. True, as blogger Ethan points out, (by far) most hydrogen gas is still present, however, by far most of this is extremely diffuse in intergalactic space, well outside the gravity influence of galaxies and not available for those galaxies, let alone for star formation (i.e. it will not contract into stellar nursery density). And indeed, galaxy wide and universally there are more very old than very young stars, even many galaxies which mainly exist of old stars (partic. elliptical galaxies).

Ethan mainly counters that there will be ‘new stars in every galaxy for trillions of years’.

I am very sorry, but I can hardly take that scientifically serious, it sounds more like wishful thinking, an astronomical ‘cri de coeur’.

Of course, there will be many new stars for many billions, maybe indeed even trillions of years, however, that is not the issue at all: the issue is *how much* star formation there is going to be per time unit and how that will add up cumulatively. Hence, Sobral et al.’s conclusion.

And this conclusion is most probably very close to the mark, take our own Milky Way galaxy as an example;

as Sobral also mentions, the MW is a relatively ´healthy´ star producing galaxy, producing about 3-5 solar masses of new stars per year (say about 6-12 new stars, since the average star is about 0.4-0.5 solar masses). The Andromeda galaxy, for comparison, produces about 1 solar mass of new stars per year.

But even the MW has stellar nurseries (molecular hydrogen clouds) for only about something on the order of 20 billion solar masses of new stars orso, maybe it is even less, 20 – 30 billion new stars. Mind, this is a very rough guesstimate and I may easily be off, but the order of magnitude is probably reasonably correct. I recently read that the MW will keep producing new stars (be it at a diminishing rate) for another 5 billion years orso. At 3-5 soalr masses per year that also corresponds to about 15-25 billion stars (not even taking a decline into the equation). The future expected merger with Andromeda will probably cause star burst but mainly from already available material, followed by a sharp decline in formation (as with many elliptical galaxies).

@Ronald,

I think this time I’ll side with you instead of with Ethan (which is a surprize to me :-).

@Rob Henry,

What an interesting view. I’ve never considered war to be anything related to altruism yet, but yes, risking your life to save others’ lives is altruistic.

I can’t quite follow all your arguments, but thanks for pointing out the “altruism in war” detail I wasn’t aware of. I don’t think it can serve as a big comfort for those losing their lives in such an event (because of a war against ETI or just against simple humans). My point is simply emphasizing that any conflict with an ETI civilization would be much worse than a peaceful trade and knowledge exchange (as any war is) but (call me a pessimist) if there are any ETIs and if they should ever come to us here, I still think a conflict has a much bigger chance than peace, just by observing human history. Yes, I may be oversimplifying, but for now I’ll stick to that opinion.

Let’s hope no ETI finds a reason to force us into being altruistic in any wars :-). To make myself clear, I would definitely prefer us and any ETI to trade and talk to each other instead of waging war.

Rob Henry said on November 10, 2012 at 23:13:

“Another example along these lines is that an ETI that has evolved from a predatory line has an evolutionary advantage for developing an ability to predict the actions of its prey. So carnivore stock ETI should have an evolutionary bias towards empathising with other species, but herbivore ETI’s would not.”

I know the finer points of the following quote can be nitpicked upon, but your statement made me think of this famous film quote:

“In Italy for thirty years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love; they had five hundred years of democracy and peace and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.” – Orson Wells, The Third Man (1949)

If we do ever meet up with an ETI in person, chances are they will not be the wallflowers of their species. Whether they are the bold adventurers, conquering marauders, or desperate refugees from their culture will be the interesting part.

Ponderer said on November 12, 2012 at 2:42:

“Let’s hope no ETI finds a reason to force us into being altruistic in any wars :-). To make myself clear, I would definitely prefer us and any ETI to trade and talk to each other instead of waging war.”

War can be very profitable too, at least for certain people and groups. Just look at how well various space agencies did thanks to World War 2 and the resulting advances in technology which came from that global conflict, such as the V-2 rocket.

Before WW2, we essentially had Robert Goddard and his private rocketry efforts being practically ignored by the general public and the government. Just over two decades after the end of WW2, we put actual humans on the Moon and had thousands of missiles with nuclear warheads atop them pointed all over the globe, thanks to a thriving and very profitable industrial military complex.

Even with a nuclear armageddon potential that has been reduced considerably since its peak in 1990 in terms of nuclear missiles (55,000 or so globaly), the US Department of Defense still gets lots of money, $770 billion annually at last count.

So as long as you don’t completely exterminate your clientele, you can benefit from war beyond the allegedly altruistic sacrifice of millions of your fellow citizens. We like to think that alien beings who are smarter and more advanced than humanity will have done away with such messy, barbaric practices, but unless every species out there is composed of saints and scientists who only want goodness and knowledge, we may learn differently.

Do you really think DARPA is sponsoring the 100 Year Starship initiative merely because they want to know what’s going on at Alpha Centauri? If alien intelligences have developed anything like us and haven’t gone on to become some kind of Artilect gods existing in an alternate universe, expect them not to do anything on such a big and complex scale as interstellar travel without motives beyond mere intellectual enlightenment.