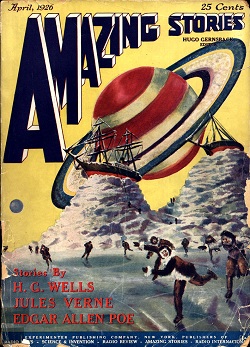

One of the wonderful things about daily writing is that I so often wind up in places I wouldn’t have anticipated. Today’s topic includes the discovery of a long river valley on Titan that some are comparing to the Nile, for reasons we’ll examine below. But the thought of rivers on objects near Saturn invariably brought up the memory of a Frank R. Paul illustration, one that ran as the cover of the first issue of Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories in April of 1926. The bizarre image shows sailing ships atop pillars of ice, a party of skaters, and an enormous ringed Saturn.

Is this Titan? The answer is no. The illustration is drawn from the lead story in the magazine, Gernsback’s serialized reprint of Jules Verne’s Off on a Comet, first published in French in 1877 under the title Hector Servadac. A huge comet has grazed the Earth and carried off the main characters, who must learn how to survive the rigors of a long journey through the Solar System, much of the time exploring their frozen new world on skates. I’ll spare you the plot details, but after a perilous fly-by of Jupiter they swing into Saturn’s realm:

…this remarkable ring-system is a remnant of the nebula from which Saturn was himself developed, and which, from some unknown cause, has become solidified. If at any time it should disperse, it would either fall into fragments upon the surface of Saturn, or the fragments, mutually coalescing, would form additional satellites to circle round the planet in its path.

To any observer stationed on the planet, between the extremes of lat. 45 degrees on either side of the equator, these wonderful rings would present various strange phenomena. Sometimes they would appear as an illuminated arch, with the shadow of Saturn passing over it like the hour-hand over a dial; at other times they would be like a semi-aureole of light. Very often, too, for periods of several years, daily eclipses of the sun must occur through the interposition of this triple ring.

If only Verne had been around to see Cassini’s images! Verne’s cometary voyagers can study the heavens with a certain detachment because the comet they are on, called Gallia, turns out to be circling back around toward the Earth, and they believe they will have the prospect of getting home. Off on a Comet is a lively tale. It would be interesting to see what Brian Stableford, who has translated so many early French tales of science fiction into English, would do with the text. Gernsback used a 1911 edition edited and I assume translated by Charles Horne, a New York-based college professor.

On to Titan

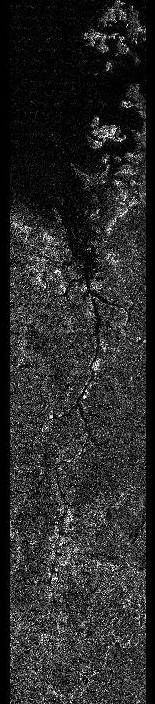

Jules Verne had no trouble concocting plots — in addition to his short stories, poems and plays (not to mention numerous essays), he wrote 54 novels in the series called Voyages Extraordinaires between 1863 and 1905. Here among much else are the familiar touchstones From the Earth to the Moon (1865), Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) and Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea (1869). We can only wonder what a Verne armed with Cassini’s latest imagery might have come up with. Take a look, for example, at the river system in the photo below. No skating here, but a boat might work.

It goes without saying that we’ve never seen a river so vast anywhere beyond our own planet, and it does bear a certain resemblance to the Nile, with which it is being compared. What Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke might have given to have had a similar aerial view of the Nile, the search for whose headwaters brought them so much grief and personal animosity. This ‘Nile’ stretches for more than 400 kilometers from its origins to a large sea, its dark surface suggestive of liquid hydrocarbons along the entire length of this high-resolution radar image.

We’re looking at Titan’s north polar region, with a river valley flowing into Ligeia Mare, a sea larger than Lake Superior on Earth. We should actually consider this river a mini-Nile, given that its namesake runs for fully 6700 kilometers, but acknowledging its unique significance (thus far) in our exploration of Titan, the comparison still seems justified. In any case, the river has much to tell us about Titan if we can learn how to read it. Thus Jani Radebaugh, a Cassini radar team associate at Brigham Young University:

“Though there are some short, local meanders, the relative straightness of the river valley suggests it follows the trace of at least one fault, similar to other large rivers running into the southern margin of this same Titan sea. Such faults – fractures in Titan’s bedrock — may not imply plate tectonics, like on Earth, but still lead to the opening of basins and perhaps to the formation of the giant seas themselves.”

Image: Cassini’s view of a vast river system on Saturn’s moon Titan. It is the first time images from space have revealed a river system so vast and in such high resolution anywhere other than Earth. The image was acquired on Sept. 26, 2012, on Cassini’s 87th close flyby of Titan. The river valley crosses Titan’s north polar region and runs into Ligeia Mare, one of the three great seas in the high northern latitudes of Saturn’s moon Titan. It stretches more than 200 miles (400 kilometers). Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI.

One day we may have a floating probe on Titan that can trace the course of such a river, working its way out into a dim sea under a sky whose dense cloud would doubtless screen the ringed Saturn from view. What a journey that would be. Even without the garish Frank Paul colors or the wild Vernian imagination, think of human instruments sending back data from a methane sea. Two proposals — Titan Lake In-situ Sampling Propelled Explorer (TALISE) and Titan Mare Explorer (TiME) show us what we might do with near-term technology to make this a reality.

Besides the sub-surface oceans theorized to exist on several moons, the surface of Titan is the only place I am aware of in the solar system besides Earth where you can get away with a simple heated suit oxygen tank. The atmosphere protects against radiation and the gravity is low enough where a human being can fly by flapping arm-powered artificial wings (ornithopters).

Titan may be a great place for recreational aviation but it is the sub-surface oceans that hold the promise of complex life. I am glad I have some experience scuba diving- it will look good on my resume when I apply for a position on the first expedition to…….wherever there is a sub-surface ocean.

Does any one else here think that sending a floating probe down such a river is a waste of mans adventurous spirit? Anyhow it would get snagged somewhere along the route.

No, this cries out for manned exploration. A team of geologists, augmented by one or two hopeful biologists must throw their barbeque (a possibility pointed out to us by JoeP commenting on Titan Exploration Options) in the back of their canoes , and set of down that river. Perhaps they can even fly back to base. It all sound like an opportunity too good to miss.

I wouldn’t hold my breath : NASA had an opportunity to launch TiME for only $425 M that won’t be repeated for another 20 (or 40, not sure) without an orbiter. Instead they chose yet another Mars mission.

I have seen it all along with Europa : 3 separate proposed missions, never eventuated. Apparently not enough money.

Fair enough, maybe but if you add Curiosity for $2.5 B, MAVEN $ 485 M, Insight 425 M and MSL2 $1.3 B, you get ~$5B all for Mars.

NASA has said that this is because humans will go there sometimes this century. If that is the case, than the extra Mars attention should come the manned space program, not the science exploration program.

This current distribution of funds is highly unscientific, not to mention that Mars looks less and less habitable as we explore it.

Unfortunately I have not heard much complaining about this huge unbalance in spending. It is as if it’s fine that such meagre funding is so poorly allocated.

That Titan river may have some beautiful pools and currents and falls and rapids as well. It must sound lively at times. The place must have a certain spirit of its own. Sort of primeval and elemental. Days and seasons passing by Titan’s own rhyme. A place in itself, totally uncaring of the far Earth and it’s over-warmed activities.

Problem is that the sub surface oceans are a couple hundred Km below the surface. Quite dark and not much free energy to “feed” an ecosystem.

Enzo- I just saw this on spacedotcom:

http://www.space.com/18901-nasa-mission-jupiter-moon-europa.html

Maybe there is hope.

Philw1776 say of Titan “Problem is that the sub surface oceans are a couple hundred Km below the surface.”, And that is like an ETI that is considering exploring Earth fretting about how difficult it is to investigate Lake Vostok.

They continue “Quite dark and not much free energy to “feed” an ecosystem.” And here we have twin problems. The best available data indicates that enough high altitude uv generated H2 flows towards Titans surface, that IF it is due to life, then we can cap its minimum activity as four orders of magnitude more powerful than the maximum for a geothermal powered Europa. A photosynthetically driven ecosystem should a few orders of magnitude more powerful again, and if it does not suffer from Earth-life’s deficiencies, then it could be several percent as powerful as our own.

And what is “dark”. Titan’s surface should be illuminated as bright as a lit room at night, or three or four hundred times as brightly as the full moon, if the usual figure is taken that it has a thousandth the typical clear-sky illumination for Earth (though I can never find it in a peer reviewed article).

Agree with everything Enzo said. The selection of the InSight mission over TiME was a tragedy. We know a great deal about Mars, and the more we know, the less interesting it is. Titan is a dynamic world about which we know very little. There is nothing that might come out of InSight that would interest anyone besides a few seismology geeks who attend AGU. But Titan! The aesthetic value of the imagery is worth the price of a closer look.

@Daniel Suggs,

Unfortunately, there is little hope : these are are just *unfunded* proposals. There are heaps of them. For Titan too. Rovers, planes, balloons, all dreams vanished by the Mars hogging.

My understanding is that, after this Mars overspending, there is little left for everything else : only some New Frontiers ($700 M) or Discovery ($425 M ?).

Anything more than MSL2 (and probably same cost) is just to expensive. See the end of this :

http://futureplanets.blogspot.com.au/2012/12/thoughts-on-selection-of-msl-2020.html

Add to the fact that NASA’s proposal system is rigged in favor of MArs (i.e. even if you propose a low cost mission like TiMe, Mars will get precedence anyway).

That is why I am complaining so loudly : NASA exploration program has been hijacked by a very narrow focus group. This is not science.

http://lifeboat.com/blog/2012/12/europa-report-reality-base#comments

Talking about subsurface oceans, here is my post on another blog if anyone is interested.

Dec 14, 2012Europa Report Reality Base

Posted by Gary Michael Church in category: Uncategorized

I was told once the secret to a good movie is suspension of disbelief.

This is a hard nut to crack for anyone making a good sci-fi movie because the closer you get to suspending that disbelief the farther away you get from what is entertaining and familiar to moviegoers.

For the true space geek sci-fi movies invariably disappoint. Anyone familiar with the basics of space flight knows things about gravity and physics that ruin any possible suspension of disbelief in these movies.

We will see how close this one comes to addressing things like:

1. Water. The minimum radiation shielding for a deep space crew is about 14 feet of water massing 400 tons for a small capsule. A living space large enough to keep more than a couple people from going crazy over a mult-year mission is going to require a water shield be in the thousand or thousands of ton range. The only practical place to get this water is the Moon. This much water is also required to run a multi-year life support system.

2. Bombs. This massive water shield means only one kind of propulsion system will work; nuclear pulse propulsion which uses redesigned nuclear weapons to shove a spaceship faster and faster with clouds of superheated plasma. This cloud behind the ship is projected against a giant metal alloy pusher plate also massing several thousand tons. These bombs focus energy in a slug which is then blasted into a cloud that pushes the ship and the filler for these slugs can be melted ice from Europa for the return flight. The only practical place to launch such a mission is the moon. No lighting off nukes in Earth orbit please.

3. Gravity. Besides radiation shielding the other necessary requirement for a multi-year deep space mission is one gravity. The way to do this with a space ship of a few thousand tons is by splitting the ship in half when not using bombs and reeling out each half on a tether for several thousand feet and spinning them around each other. The pusher plate can be kept in the center of this system while the nuclear reactor and stores can be at one extreme and the shielded crew section at the other.

This is the basic minimum spaceship for a trip to the outer moons. How close will this movie answer these basic space geek requirements of Water, Bombs, and Gravity?

I am starving for some suspension of disbelief.

Enzo, I think that NASA priorities are even worst that just “Mars first”. As a twelve year old schoolboy, I marvelled at Vikings ambitious search for signs of carbon based life. I was astounded at the ambiguous results, and fascinated by the given interpretation. It seemed that they found an incredibly exotic minerals that oxidised organics when humidified, and that synthesised new complex organics when exposed to ordinary visible light.

At the time I felt sure that they either planned further follow up tests, or that they had worked out what this exotic mineral could be. For much of the next decade I read all I could on this matter to discover the answer. Now I realise that they just yawned, and said “biochemical tests for life look a bit to academically challenging for us, lets just search for water instead.”

I just thought of a better way to rebuff philw1776’s dark and low energy comment. Titan’s sunlight seems to be about a quarter as intense as on the floor of a tropical rainforest. If you note how much growth there is in that situation then divide by four, you would have it. This is obviously much more powerful than anything still possible for Mars.

Sure, this might be disappointing to those who hoped that we might have to fight vast herds of carnivores. They will have to lower our sights to tussles with smaller packs of carnivores or vast herds of herbivores.

@Daniel Suggs,

I forgot to mention that, currently, the only real chance to have a mission to Europa is ESA’s two flybys as part of their Ganymede orbiter, sometimes in the ’30s.

ESA has no RTG (so they’ll use solar panels) and limited radiation hardened technology (otherwise they would hopefully choose the much more interesting Europa).

Titan is also much more interesting than Ganymede but it is too far for solar panels. Another unnecessary sacrifice to Mars was using RTG for Curiosity in a place where solar panel have been shown to work for years.

All they needed was an inexpensive (compared to RTG) device to clean the panels but no, better take the little plutonium left instead.

A collaboration between ESA and NASA could let us see a mission to Europa or Titan but I wonder how is ESA feeling now that NASA has screwed up ESA’s ExoMars rover by announcing their withdrawal for lack of funds while, at the same time, announcing their own new rover (MSL2).

This should do wonders for future collaborations.

@Rob et. al. Please read carefully. I am talking about the water oceans 200Km BELOW the surface. Surface insolation figures you quote are irrelevant.

Regarding the current direction of NASA, sure Mars is an interesting planet, but perhaps after the huge budget overruns of MSL it is time to give other destinations something of a look-in. I suppose we should count ourselves very very lucky that we had Voyager 2 when we did. Given the current interest in super-Earth planets, it is high time to return to Uranus and Neptune. But I don’t see it happening any time soon. :-(

Philwi, your brevity caused ambiguity. Now I have a new pair of problems.

1) I am stunned that you do not find the meteorology and surface geology here fascinating. While you are stuck in your slowly descending bathyscaphe we are flying through the air (often under our own power), skying, scooting down rapids, and splashing through the oceans, and even barbequing chicken on the surface. All in the name of science – of cause.

2) Yes you would be in the dark, but consider this – since you’re bothering to be our sub captain, we must have found the surface devoid of biota. All those high energy chemicals, and disappearing H2 must be going somewhere, and if all are absorbed and buried without reacting till they reach that internal ocean, this would provide at least 20W/sqkm energy, and I would guess it could even be 200W/sqkm. Thus Titan’s subsurface ocean could provide 20,000 to 200,000 times as much energy as a purely geothermal driven Europa. The key is that titans complex surface allows a greater range of extreme possibilities for transport from the crust than Europa, and its atmosphere provides more potential for creating high energy compounds.

@andy,

There was a serious proposal for an Uranus orbiter now that it looks like it has developed some weather after reaching the equinox :-) :

http://futureplanets.blogspot.com.au/2011/01/uranus-orbiter-concept-study.html

And this freshly posted Enceladus sample return :

http://futureplanets.blogspot.com.au/2012/12/life-sample-return-for-enceladus.html

All unfunded dreams of course, with $5 B all allocated to Mars.

@Enzo: yes a mission to Uranus at equinox would be a very interesting one: it is a pity that when Voyager 2 went past the planet it was at its blandest. I was quite disappointed this one never made it to reality. The atmosphere changes would be interesting to watch if you can afford to keep the mission going for a few decades (of the giant planets it is the only one where solar heating dominates over the internal heat source), and of course we still have seen only a fraction of the surface of the moons, several of which show some extremely interesting landscapes.