These days we know that perhaps a million objects the size of the Tunguska impactor or larger are moving through nearby space, and talk of how to deflect asteroids has become routine. Given our increasing awareness of near-Earth objects, it wouldn’t be a surprise to hear of a new Hollywood treatment involving an Earth-threatening asteroid. But I wouldn’t have expected a science fiction series that ran from 1959 to 1960 would have depicted an asteroid mission and the dangers such objects represent.

Nonetheless, I give you “Asteroid,” from the show Men Into Space, with script by Ted Sherdeman. Viewers on November 25, 1959 saw the show’s protagonist Col. Edward McCauley (William Lundigan) take a crew to ‘Skyra,’ a 3.5-kilometer long rock that scientists believed might hit the Earth. The crew assesses whether the asteroid is salvageable for use as a space station and decides there is no other choice but to destroy Skyra, which they do at the cost of considerable suspense as McCauley works to save an astronaut separated from the others while the clock ticks down. The suspense would have been heightened by the fact that this was a show on which astronauts sometimes died and hard sacrifices were the order of the day.

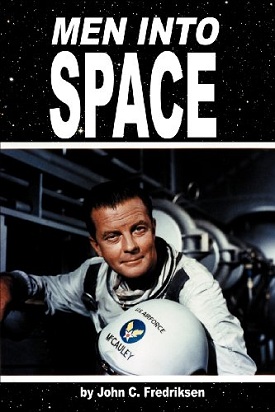

I report on all this with the help of John Fredriksen’s new book Men Into Space (BearManor Media, 2013), which arrived in the mail the other day. Like me, Fredriksen had watched the show in its all too short run while growing up in the Sputnik era. He was taken with the understated but tough role of McCauley, who was depicted as participating in all the significant space missions of his time, from the first lunar journeys to building a space station and, at the time of the show’s cancellation, two attempted flights to Mars that were plagued by problems and aborted.

You could say that Mars as a destination hovers over all this show’s plots. Its final episode, “Flight to the Red Planet,” did get McCauley and team as far as Phobos, where their ship was damaged enough to force an early departure without landing on Mars itself. The Mars of this episode is a compelling target, because from Phobos, in these years not long before Mariner 4, the crew can see waterways that seem to be feeding an irrigation system. This is Percival Lowell’s Mars in an episode surely designed to build into a second season, but that season was unfortunately not to be.

Fredriksen’s book walks fans through all the episodes, with extensive quotes from the scripts and stills that capture the look and feel of the production. If some of these images seem familiar, it may be because Chesley Bonestell was asked to produce concept art for the show, resulting in sharply defined lunar landscapes reminiscent of his paintings. Lewis Rachmil, who produced Men Into Space, would have been familiar with Bonestell’s Hollywood work, which included Destination Moon (1950), When Worlds Collide (1951) and Conquest of Space (1955), not to mention the famous space series in Collier’s.

Frederic Ziv, who headed up ZIV Productions, didn’t stop with Bonestell when it came to making his show as realistic as the times would allow. Sputnik had been launched in 1957 and Ziv had been exploring doing a different kind of space show for CBS ever since. From the book:

Unlike the children-oriented science fiction programming of a few years previous, the tenor of the times now demanded an approach that was rigorously scientific to appease more mature audiences. Ziv, who prized flaunting the technical expertise assisting his programs, also believed that obtaining Department of Defense cooperation facilitated access to their extensive and elaborate space facilities. At length, his show acknowledged help from the Air Force Air Research and Development Command, the Office of the Surgeon General, and the School of Aviation Medicine. Ziv’s credibility was further enhanced with Air Force technical experts who were brought into the scripting and consulting process, receiving credits in the end titles.

Couple this with location shooting at research facilities like Edwards Air Force Base and Cape Canaveral and stock footage of missile launches of the time, along with special effects crews working with von Braun-style three-stage rockets launching capsules that were almost as tiny and cramped as Apollo. Men Into Space turned out to be complicated and expensive. Fredriksen notes that ZIV gave the Air Force the final say in keeping the show realistic, which is why the more fantastic tropes of 1950s science fiction make no appearance. Personality conflicts and equipment malfunctions took the place of ray guns and aliens.

Fredriksen gives all the details, including a summary of each of the show’s 38 episodes. It’s a nostalgic trip for those who remember watching Men Into Space, and it brings back to life memories many of us had long forgotten. After all, this was a short-lived series that survived only in occasional syndication and in some of the space suits and ship interiors that wound up being used again in episodes of The Outer Limits (I knew they looked familiar!). Nominated for a Hugo Award in 1960, the show lost out to The Twilight Zone, and critics sniped at its mundane special effects and earnest quest for authenticity. Despite the promise of Mars, the show was axed in September of that year.

But early impressions count, and it’s safe to say that this show captured more than a few young minds, not the least of them being Fredriksen’s, for whom the experience was indelible:

May future generations rekindle that sense of awe, the ability to dream a better future, and a fixed determination to cross the gulf separating imagination from reality as we did, and joyously so, in the 1950s. If Men Into Space encapsulates the essence of a departed, heroic ideal, it is also a good measure of everything we have lost as a space-faring culture.

As for me, I’ve always been a William Lundigan fan. This is a guy who walked away from Hollywood in 1943 to join the Marines, where he served with the 1st Marine Division on Peleliu, an operation that ranks with Iwo Jima in terms of the ferocity of combat and the staggering percentage of casualties. He went on to Okinawa as a combat photographer and, having received two Bronze Stars, returned to acting after the war. 1954’s Riders to the Stars was his first science fictional outing in a show about astronauts trying to capture meteorites in flight. His work with Ivan Tors on that film fed into a role in the series debut of ZIV’s Science Fiction Theater.

Of Men Into Space, Lundigan would say: “…this was not some Buck Rogers type show. It was not a science-fiction series but a science-fact series. You might even say it’s a combination of a public service show and a dramatic series.” Even he would become exasperated with the quality of writing in some of the later shows, but as Fredriksen’s book makes clear, there was still inspiration to be found here of the kind that awakens young people to careers in engineering and science. With a little better luck and a second season landing on Mars, Men Into Space might be far more than the obscure recollection it is today, and the name ‘McCauley’ might be as recognizable as ‘Kirk.’

Nice trip down memory lane, thanks. I remember too an excellent late fifties Disney show with the same name featuring Wernher Fon Braun. Remember the clear distinction between SF and fantasy? Ray Bradbury knew the difference and was grand at both.

How could we have morphed “Sci-fi” into the fairy-tale fantasy soap operas of today? Yet the kids seem to love it. “Attack of the Vegan Zombies” !? Groan…PS, Isn’t “The Blob” about due to thaw out, with global warming and all? I Thing a sequel is in the making.

I have DVDs of all the episodes. MIS is why I became a space freak. I’m 57 now, and was three going on 4 when it aired. It blew me away.

So now we have a book about it? Damn! Yow! Gotta get it…

I love sci-fi but not the downside to it; fiction crosses the line into fantasy far too easily. Most people do not understand the difference between what may be possible now and what might be possible in ten thousand years after we learn to break the laws of physics.

Star Trek is of course the example that is most illuminating. This series was a Horatio Hornblower in space concept and mixed up the maritime past with the spacefaring future; the two have very little to do with each other and there is the root of the problem. Space is not an ocean.

Interstellar travel is a one-way trip into the future. It is space and time travel which is not what hollywood scriptwriters can sell; people are not comfortable with it.

Time frames are in centuries for star flight. The only way to survive is suspended animation. That is, unless very high fractions of the speed of light are attained- which takes fantastic energies that are probably a couple centuries down the road at least. Very few movies depict this first reality check that star travel is time travel and when you leave you are leaving everything on Earth hundreds of years in the past.

Thanks, Paul – just ordered the book. I first saw MIS on the SciFi channel (back when they showed real science fiction) and was hooked. It’s too bad that the show didn’t last and that it’s only available as bootleg DVD copies of the aired episodes.

I too have fond memories of that show and of it’s star. Which is odd, because I was very young at the time and don’t think I saw it in repeats. I remember it for it’s drama and accuracy, the latter of which is also odd as I couldn’t have known much real science at the time! Thanks to Tim Kyger mentioning he has DVDs of it, I’ll have to go do a search for them.

I missed that one, though I’ll certainly look into it. The TV show was way ahead of its time. Shoemaker-Levy 9 chnged everything, the 21-fragment comet that impacted Jupiter in July 1994 (it was first spotted in March 24, 1994). The impacts were far and away the most energetic events ever seen in our solar system. This drum-rolling event, of course, led to the NEAR (Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous in 1996) mission. Launched February 17, 1996, NEAR was a four year journey journey that included fly-bys of asteroids Matilda (June 1997) and Eros (Dec. 1998) and began orbiting the latter on Valentine’s Day (curiously enough) Feb. 14 2000. It snapped 69 high-resolution photos of Eros during the final few minutes of its descent, from as close as 394 feet.

Hard science fiction novels and TV shows don’t sell as well as their fantasy varieties. But nothing beats realism, though.

Speaking of “men into space” I am somehow reminded of a little-known biography by Martin Caidin called I AM EAGLE (1962) about the life and career of Gherman Stepanovich Titov, the second man in space (the first being Gagarin). It was from this book that America got its first look at the Soviet space program, since a significant number of photos were made available to NASA (and various intelligence agencies) showing never before seen facilities and hardware. The West knew virtually nothing about the super-secret Soviet space program at the time. Titov later headed up the Baikonur cosmodrome, and in 1989 greeted western reporters at the cosmodrome for the first time.

Men into Space was an odd show. What I call Popular Mechanics science fiction. I remember watching it but being a rabid reader of SF prose.. it and , gad, ZIV’s Science Fiction Theater never used prose SF as a source. Men into Space was a little more entertaining while, I thought, Science Fiction theater was industrial strength ennui!

Twilight Zone had also started in 1959 but lasted 4 more years. My feeling is it was because Rod Serling was familiar with prose science fiction. He even adapted stories by Robert Block, Damon Knight,Lewis Padgett a few others.

His own teleplays the first season were quite good, alas he was somewhat uneven after that…. while seasoned SF and fantasy writers Charles Beaumont, Richard Matheson turned out the finest TWZ teleplays. Ray Bradbury did at least one teleplay.

Alas, and I have never figured out why prose SF has served as such a small source for film an TV drama. It is beyond me. Many ideas were lifted. Before Gene Roddenberry became famous I did get to talk to him once and said Star Trek sure seemed in the spirit of modern prose SF. He said “you should”! He had been (don’t know if he stayed so) an avid reader of prose SF from the middle of the 1940s.

It’s still a puzzle as why there was a ten year gap between Forbidden Planet (1956) and Star Trek (1966) for ‘sort of’ sophisticated Space Opera. It had existed on the pages of John Campbell’s Astounding since 1938!

The prose form was even light years ahead of Forbidden Planet when it came out.

Some SF I think is just too ‘advanced’ for the average viewer , Ursula K. Le Guin’s off scale Left Hand of Darkness will never be made … Alfred Bester’s pyrotechnic baroque space opera The Stars My Destination still sits idle , 7 screenplays have been done of it, one my Bester himself! It’s got all the ‘right stuff’ for SF that Hollywood wants!

All of Heinlein’s so called ‘juvies’ would be perfect , only a little updating needed , he was a grand master story teller.

(Of course Star Ship Troopers did get trashed by Paul Verhoeven so you never know.)

Correction: among the typos in my post is a mistatement of fact which I should like to correct here. Shoemaker-Levy 9 was first sighted on March 24, 1993, not 1994. The “drumroll” lasted 16 months (not four months).

Very few people seem to remember this once-in-many-lifetimes event today, though the scientific literature will recall the incident for a million years, at least. Astronomers changed their opinion about the likelihood of cosmic impacts on a dime. Uniformitarian (geologic) theory took a beating with this one, while catastrophism theory made a comeback. It takes a lot to change scientific opinion on a dime, but then SL-9 was a lot.

Hollywood’s inability to to turn out good Si-FI is a total mystery to me. They just have no feel for it.

That grotesque parody of Heinlein’s Starship Troopers was a major disappointment.

Remember the first “Dune” movie by Deno De Laurentiis, with the comic-opera costumes? In a later interview, De Laurentiis said he never bothered to read the book…

“I have never figured out why prose SF has served as such a small source for film an TV drama. It is beyond me.”

Books can fill in the backstory and fully develop the story arc which is critical in SF because since it is a different world it has to be described fairly completely for any suspension of disbelief to occur.

Historical work is easy to manage because the audience has the given belief that this is history and the story or something like it actually occurred. Not so with SF. Unless you are going to mix up genres like a pirate movie in space (Wrath of Khan- the only star trek movie I like).

Starship Troopers is also one of my favorite movies and still plays well while the book does not read well today. Verhoven’s masterpiece is a crossover into monster movies which also works- as Predator and Aliens has shown. Monsters are a good trick to draw the viewer into a future world by using inherited instinct; no one wants to get ate.

One of my favorite science fiction movies is still “Fahrenheit 451”, from the very recently late Ray Bradbury’s book of the same name. I don’t see any of the TV channels rerunning the Francoise Truffaut-directed movie to celebrate the great writer, probably because it hits too close to home with what’s happening politically today. The endless war background is central to the book but is not mentioned in the movie, but there are other themes areas that speak to today. Hollywood is the capital of “political correctness” propaganda, so it probably won’t be aired anytime soon. Same with “Brazil” — a brilliant and wildly creative film directed by Terry Gilliam about a super-paranoid future totalitarian dystopia in which torture is routinely used by the state. The other film of note in the social-science fiction genre that you won’t see on the boob screen is “THX-1138” directed by George Lucas. I think this was his best film by far, and the first film he ever made.

Modern Hollywood science fiction movies cannot be allowed to make people think. They can have all the technology in the world and bug-eyed monsters, but social commentary is verboten, which for me tends to negate its greatest value. They’re pretty much “disaster movies” now, which I find shame.

“The Stars My Destination still sits idle , 7 screenplays have been done of it, one my Bester himself! It’s got all the ‘right stuff’ for SF that Hollywood wants!”

Maybe what Hollywood wants but it is not good for the cause of space exploration. Brainless eye candy has all been done with the Star Wars franchise; we need people to think about the near future- not some fantasy centuries in the future or in a galaxy far away.

Jules Verne writing in 1865 definitely inspired the U.S. space program of 1965; there is no doubt about this. But what is inspiring our young people today are miracles that cannot possibly be construed as real possibility.

“That grotesque parody of Heinlein’s Starship Troopers was a major disappointment.

Remember the first “Dune” movie by Deno De Laurentiis, with the comic-opera costumes?”

Starship Troopers the movie was not Starship Troopers the book. Get over it. It is really a completely different story in the movie and I do not deify the book as others do; the powered armor was great but the story was……juvenile. I have continued to watch the movie every once in a while over the years and still guffaw at lines like, “They sucked out his brains!” It is a classic.

Dune was not the greatest read in the world either IMO; the knife fighting and dependence on a resource from the desert was interesting but the rest was far too complicated and fantastical. It is failure at the opposite pole of Starship Troopers the book which was not complicated or fantastical. The movie adaptions of Dune and Starship Troopers are as different as night and day.

My nomination for a sci-fi book that would make a good movie is “On Death Ground” by Weber and White. No big concepts to get across, no great mystery to unravel- just spaceships blowing each other up. And this kind of story can be fashioned to make space less fanciful and more concrete for the public and thus increase support for space exploration.

Thomas: “Uniformitarian (geologic) theory took a beating with this one, while catastrophism theory made a comeback.”

Is this a joke or are you truly so misinformed?

I suspect one big disincentive for realistic SF is the discovery of the “dull” Solar System – that all the quasi-scientific claims of life on Mars or Venus that had inspired 30s, 40s and even 50s “realistic” SF has proven wrong. Venus is too hot to land on and Mars is more Moon-like than “Antarctica-like”, while the canals have proven to be illusory and even the wave of vegetative growth, that seemed so certain, has proven to be dust related. Sure, we have entrancing worlds further out – Europa, Titan, Enceladus – but they’re all impossibly far away for current technology for one reason or another.

Ron S, I think there is a grain of truth in Thomas’ uniformitarian comment. I think that that principle had been sufficiently oversold that geologists took an excessive amount of time to put together evidence for supervolcanism and for biologists to believe that meteorites, supernova, or global geochemical phenomena could explain mass extinctions. To me, Thomas’ bigger failing was to think that this began the shift in outlook, rather than finished it.

Complacency is one danger to us all. The paradigm approach to science is an another.

Actually Ron my last comment was prompted by my disappointment. The public gallery of our local Carter Observatory was packed for the Shoemaker-Levy 9 impacts, despite predictions that nothing obvious would be observed from these far side impacts. The reality was that they were so bright that they saturated the display and Jupiter disappeared, leading to many comical remarks, but, to me, there could hardly be a greater portent. If only the general public could separate fact from fiction they would have finally been able to see that far more public money should be spent on noncommercial science and preventive technologies than on art or sport.

“Sure, we have entrancing worlds further out – Europa, Titan, Enceladus – but they’re all impossibly far away for current technology for one reason or another.”

Completely possible with current technology. No reasons except that cold war toys are easy money and spaceships are hard money- they have to work.

We have a Heavy Lift Vehicle on the way that can soft land payloads at the lunar pole near the ice. The Moon is outside the Earth’s magnetosphere and is thus ideal to assemble and launch any kind of nuclear propelled vehicle. The ice as water can be used to shield the spaceship crews from long duration cosmic ray exposure and solar events and also as a multi-year life support system medium.

On the other hand, pretty much every single Philip K Dick novel has been turned into a movie, many of them high grossing modern action movies. Some quite good. Blade Runner of course being the most famous example, Total Recall now having been done twice, Minority Report, and a host of others. If you check closely, you will find that quite a lot of movies that you wouldn’t think right away had anything to do with prose science fiction are actually based on a classic story, without being billed that way at all.

Arguably you could say: Yes, the time of the sci-fi movie is over, but not because it has disappeared, rather because it has gone mainstream, quietly and unnoticed.

I won’t comment on Verhoeven or de Laurentiis…

Ron: What exactly is your problem? You don’t explain. Before SL9 was discovered in 93/3, the prevalent theory of geologic formation was uniformitarianism, the theory that physical, chemical and biological processes on Earth have operated with general “uniformity” through immensely long periods of time and are sufficient to account for all geologic change. The concept was first advanced in 1785 by the Scottish geologist James Hutton in his book THEORY OF THE EARTH. This theory was in direct opposition to the previously held, biblically endorsed theory of catastrophism, which holds that at intervals in the Earth’s history all living things have been destroyed and replaced by entirely different populations. Of course, the debate has its roots in the older rivalry between science (Galileo) and the Church. The fact is both geologic processes share in the work of terra-forming our planet. Due to SL9, geologists have sought a synthesis between the two views (now called neo-catastrophism and uniformitarianism).

Before SL9, the prevailing theory in geology was that large comet and asteroid strikes were a thing of the far distant past; Eugene Shoemaker’s impact theories were pretty much laughed off, his theories considered fringe geology. Tungusta? Well, that was “anecdotal” and happened only once. Craters on the moon? Well, those could be extinct volcanos, etc.

@Gary

“Dune was not the greatest read in the world either IMO; the knife fighting and dependence on a resource from the desert was interesting but the rest was far too complicated and fantastical.”

Dune is the novel John Campbell* could never get out A. E. van Vogt!

van Vogt was a great short story writer, and his novels have pyrotechnics , but he was a lousy writer at length.

Campbell loved because of a life long fascination with PSI powers.

Dune had that and more , good writing!

But I agree , as SF prose, lord there are writers who have Herbert beat by light years, Theodore Sturgeon was a writer’s writer , but even the big three,Asimov, Clarke and Heinlein did way better … Cordwainer Smith is one of my favorites, unjustly not known well.

David Lynch tried very hard to make something out of Dune, he wanted a 6 hour or two three hour films but ol Dino would not stand for it.

Funny , as opposed to what’s stated above, I thought the sets and costumes captured the novels vision… the VFX were really hit and miss.

My favorite SF film, and the only one I know of that was made in the spirit of modern SF prose is 2001:A Space Odyssey , it’s a Big Thinks story, and with FX work that is still hard to believe , way way before digital VFX.

*By the by Asimov and Heinlein both stopped writing for Campbell by the late 50’s because he kept wanting to see PSI stuff in them. Asimov in particular could not abide this.

Thanks for your clarification, Gary. You’re probably right that SL9 “finished it” rather than “started it,” though I doubt if Eugene Shoemaker would be on board with this. Until SL9 went down, he had one hell of a time getting his theory across to the “mainstream” of geology. (One needs to choose words carefully in a forum like this.)

Thomas,

So if there is even one concentrated energy input to a system (what you seem to mistakenly label a “catastrophe”) that says that catastrophism comes to the fore? No. Catastrophe-driven stories of history have ancient roots (and in today’s entertainment industry!) but that is very far from the dominant role played by long-term pressure of more gradual change in geography (or cosmology). The reason is simple enough: that while spectacular, the energy surge by, say, a comet hitting Jupiter is really quite tiny in the long run (and even in the short run). Yet it was you who made the extreme statement that SL9 brought catastrophism to renewed prominence. And Tunguska? Same thing: very interesting and important but not so much as a blip in Earth’s geologic history. Even the suggested dinosaur-killing asteroid, while profound in the short-term, didn’t have a chance against longer-acting, overwhelming forces of geological and biological development.

“If only the general public could separate fact from fiction they would have finally been able to see that far more public money should be spent on noncommercial science and preventive technologies than on art or sport.”

Amen Brother. We need to protect the Earth from impacts- that is the major issue behind any space discussion IMO.

To Thomas Hackney, Hadn’t uniformitarianism fallen out of favour in geology long before Shoemaker-Levy 9’s impact with Jupiter because of the wide spread acceptance of plate tectonics theory?

I was somewhat surprised to read your assertion that geologists still accepted only uniformitarianism as an accurate explanation of Earth’s geological features as recently as 1994.

I thought plate tectonics had discredited that old theory back in the late 1960s/early 70s. Would be nice if there are any geologists reading this blog

who would like to comment.

Thomas Hackeney, perhaps Ron S’ problem with your posts is that he doesn’t like science or its history reduced to the comic book level, and it is likely that your numerous errors in detail exasperate him. More study on your part, and a greater deference to subtitles will help no end here.

My understanding of uniformitarianism is that it basically refers to very gradual processes taking millions of years. By contrast, my understanding of catastrophism is that basically it refers to large and sudden changes, such as that caused by a large asteroid strike, super-volcano, solar hiccup or pole shift. I do not take one side or the other. If I’m wrong I’m wrong and don’t mind being corrected by those with superior knowledge on the subject. Thanks to all.

Mike, I think that the Continental Drift saga is more to do with a meteorologist stealing a march on the best and brightest geologists. Actually I’m not entirely sure that it doesn’t reinforce uniformitarian principles more that it challenges them. With this abysmal current paradigm approach to science, it doesn’t matter how much better your new hypothesis fits the facts, or how great its predictive value. If your opponents have spent decades painfully amassing data showing that the mantel allows the transmission of S waves your hypothesis must be wrong end of story. We are forced to wait decades till will can explain the anomaly before we are allowed to take the next step.

Rob, in case you haven’t noticed, we’re living in a comic book world. I am not a scientist, but I am aware of political and social trends, especially as these impinge upon science. Much science is funded by foundations and legislation with certain agendas in mind. Global warming science, for example, is not science, it is propaganda. More than ever, the modern scientist needs to be aware of some of this. Science is a group-think endeavor, but it is usually advanced by brave individuals who think outside the collective box.

Regarding your recent point above, anomolous phenomena is not something science is set up to investigate, since by its very nature it is anecdotal, spodaic and unpredictable. Science requires multiple if not predictable occurrences. Stuff that hapens all the time is the easy to observe and investigate; stuff that doesn’t is where it gets hard.

Mike: I would think that plate tectonics activity supports uniformitarian theory since it happens quite slowly.

The Big Bang Theory (not the CBS Television series) suffered in a similar fashion as the idea of continental drift, with the Big Boys of Science not accepting it right away in part because it sounded too much like a divine creation story (let there be light). Before that idea, mainstream science actually bought into the concept that matter was constantly being made to add to the Universe known as the Steady State Theory, though where and how all this matter came from was never quite stated. How that was any better than the BBT in terms of scientific plausibility I do not know.

I distinctly recall an article in Scientific American shortly after Penzias and Wilson detected the cosmic microwave radiation (CMR) in 1965 that had the author lamenting the loss of the SST. I felt like I was reading the treatise of some Renaissance astronomer who was going to miss having Earth be at the center of the Sol system (and by default the entire Universe) because of those guys Copernicus and Galileo and their radical notion that our planet is just one of many circling the Sun and by default our shining yellow orb was just one of those countless stars we see in the night sky, which would mean that they might have their own retinue of planets circling them and on those worlds might dwell… oh my.

Even Penzias had trouble with the meaning of their findings at first:

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dp65co.html

It still boggles my noodle that mainstream astronomy did not accept the idea that there was more than one galaxy in the entire Universe until the 1920s! In many respects we are not that far from the Middle Ages when it comes to solving cosmic mysteries, especially the one about alien life.

As for science fiction in television and film, I blame Star Wars for derailing what had been a growing trend for good and true SF cinema that had begun just a decade before George Lucas went from his THX-1138 to the far more lucrative but much less cerebral fantasy space battles franchise. There have been a few good SF films since 1977, but nothing compares to the era which included such notables as 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Andromeda Strain, Dark Star, Rollerball, Solaris, Silent Running, Soylent Green, and the original Planet of the Apes (screenplayed initially by Rod Serling no less).

After Star Wars the genre went from films that focused on plots, characters, and especially big, socially relevant ideas to big budget special effects, cardboard cutouts for characters, and plots that could have been conceived by a 12 year-old (and probably often were). Even remakes of classic SF films from that glorious and all too brief period were ruined by the (lacking) sensibilities of the post-Star Wars era: The Andromeda Strain and Rollerball “reimagings”, as just two examples, did just about everything wrong that the originals had done right.

This pattern of derailment will probably remain off track for decades to come despite a few good efforts to get back on the trail forged by Kubrick and others (Blade Runner, Moon, and In Time are a few examples). Hollywood is dominated by people who are not into science fiction or science, will never get it, and only care about the bottom line. Note how every year at the Oscars that most of the films they put up for the awards tend to be ones that most people have not seen. I am generalizing here, but only to a degree.

And who knows when we will ever see a good SF film even get nominated by the Academy. I recall distinctly how the 1997 film Contact got snowed by Men In Black in just about every category they were nominated for. Contact was not a perfect film and MIB was not a terrible film, but the former was at least a plausible attempt at depicting a METI event and bandied about ideas not normally found in a mainstream film. MIB played heavily into the UFO mythos. Of course the latter one did better financially and in the minds of the general public.

Here is my take on one film from SF cinema’s golden era, Silent Running, which includes my thoughts on the subject of pre and post-Star Wars era:

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1337/1

GaryChurch wrote:

“Amen Brother. We need to protect the Earth from impacts- that is the major issue behind any space discussion IMO.”

** GOLF CLAP ** Yes–space development should be pitched to industry, politicians, and the general public as the ultimate “making lemonade out of lemons” scenario, which it is. Now:

If I was doing it, I’d start with a slide show, whose first image would be of the Barringer Meteor Crater in Arizona. I’d say, “I’m sure you’re familiar with Meteor Crater in Arizona, and you probably also know about [changing the slide] the Wolf Creek Crater in Australia. But do you know about…” [as I clicked quickly through slides of the other astroblemes on Earth], saying “each of these craters resulted in instant death in its vicinity, followed by massive forest fires, dust-dimmed sunlight, falling temperatures, and finally starvation over large areas of the Earth.” Then:

After showing a two-hemisphere drawing slide marked with all of the Earth’s craters, I would bring up an overhead view of the Chicxulub crater, with its diameter marked on the image. I would say, “This crater is why the dinosaurs are gone, and why *we* aren’t hissing and roaring at each other today. If we do nothing, one day another impact like that one *will* wipe us out, too–it is only a question of when. But those same hurtling celestial stones that threaten to annihilate us also offer the promise of safety, wealth, and longevity for the human race–both on Earth and in space–for they contain vital industrial metals and minerals that are rare on Earth. They also contain chemical feedstocks that can support enormous human populations throughout our solar system–and beyond. The asteroids, the greatest threat to our existence, also offer the greatest opportunity to us and to our descendants. In other words, we can turn these cosmic lemons into celestial lemonade–and generate undreamed-of wealth in the process.”

— Jason

Bear with me, as I prep my point with an analogy:

__ In the 60’s “slot cars’ were a hot thing, but that hobby fizzled out. That hobby has now been reborn. Even though the slot car consumer market is small, the slot car companies can now easily reach that full market via the Internet. There is enough business to keep a few companies viable.

__ My Point: Fans of hard sci-fi might be few, but there are enough (I think) to enable small movie producers to cater to that audience. Distribution can be via the web, not theaters. While Hollywood caters to the mass-audience block-busters, I would love to see a small production company create hard space movies for this niche market. AND, I suspect the real market and fan base is bigger than business goons assume.

What would you guys be willing to pay to download some well-done hard sci-fi about space? And how many of you are there?

With my point raised, I now digress into angst about space movies:

– The lack of sound in space could be used to dramatic effect, instead of abandoned in favor of famil-e-‘air’-ity.

– Make the rate of explosions or impacts to true scale and time-rates.

– Follow Newton’s laws – especially regarding free-fall conditions in space.

– Have professionals behave as professionals (instead of like high-school students in a cafeteria).

– Draw plot elements from real possibilities, which are numerous and as yet not well done (fungus in space, loss of air-handling equip, micro-meteor impacts, space radiation, long-duration strains on crew health [physical and mental], real types of common malfunctions, etc).

– If you have aliens, make them alien and do not cheat around the issue of dubious communication. Heck, we human-to-human communication is fought with errors, communicating with an intelligent water creature in Europa.

AND… if you want to venture into speculating on undiscovered propulsion physics, be self-consistent with how it is employed. If you show gravitational fields inside a ship (for normal walking around), that ability implies a host of other functions that would then be possible too. If you do FTL, be consistent with time/distance mismatches, and be consistent on how you are interfering with the normal propagation of light and other EM properties.

Nuff said,

Marc

After 2001:A Space Odyssey was mentioned I felt urge to add to the list a Soviet era movie Planeta Bur [??????? ????] (Planet of Storms). It’s 1962 movie of an international space mission to the palnet Venus by Pavel Klushantsev. Probably none of you have seen except those who remember Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (1965). That one ise direct Hollywood rip-off of the original. The scenece w/ the blonds were added for some reasons. Pavel Klushantsev’s work is actually the reason why Stanley Kubrick decided that it’s ripe for 2001:A Space Odyssey. He saw Klushantsev movie The Road To The Stars especially the scene of astronauts beign in weightlessness and he was blown away by the SFX. Bear in mind Road To The Stars came in 1957! Even before Sputnik was launched!! The KGB suspected that he knew the secrets but actually he made the calculations and design of space crafts by himself which turned to have remarakable similarities w/ the actual rockets. The fact that Klushantsev work had influence on Kubrick 2001, Lucas Star Wars IV and Cameron Terminator is little known fact even in Russia. He developed many SFX technique for the era and even managed to excel the peers.

Remarkable is the fact that the Planeta Bur escaped shelving by a notch after Minister of Culture reviewed the movie and insisted that Soviet women in space can’t cry even in desperate moment! Well the crew and other managed to dodge the ciriticism and the scene is in the movie.

Planeta Bur (Wiki) – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planeta_Bur

Road To The Stars (Russian version) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mXt30Ing3Kk

Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (1965) (Dubbed in English ;) ) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c3xKXrmFcWc

Copernicus and Galileo did not believe the sras were suns. The plants were wandering stars, not planets like Earth. Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) was the philosopher/priest who first posited the idea that the stars were suns shining from very very far away, that planets revolved around these suns just like here (because he accepted Copernicus’s heretical theory that the earth went round the sun). He even went so far as to posit that extraterrestrials must live on at least some of these planets because why would God go to all the trouble of creating so many suns and planets if not to populate them? Galileo laughed off Bruno as a crank, of course, calling his thoery “wild and unprovable.” No, Aristotle’s model of he universe was the accepted idea, but Bruno said Aristotle was wrong, and was later burned at the stake for his wild and unprovable notions, notions he refused to recant, unlike Galileo 20 years later.

Bruno observed that the stars twinkle, and only appear small because they are so very far away, i.e. he used his eyes and brain!

Corrections: Copernicus and Galileo did not believe the STARS were suns. The PLANETS were wandering stars, not planets like Earth. …

Great discussion. Uniformatism died long before SL9. My wife loved looking at the “smash marks” on Jupiter thru my 8″ Celestron.

ljk’s great comments on the lamentations of steady state.

I do take exception to the travesty that was the film “Starship Troopers”, OK except for the excellent shower scene. I like some of Verhoven’s other work, notably the excellent “Black Book”, but Troopers should damn him to hell.

ljk: Thanks for the link to the very thoughtful article at the end of your missive! He missed two great movies in his list of important pre-Star Wars era sci-fi films: “The Day the Earth Stood Still” (1951) and “Fahrenheir 451” (1966). The influence of these two movies exerted on my boyhood mind was profound; I probably would not have turned into the adult I did without them. Since I already touched on the “Fahrenheit” in an earlier post, I’ll just briefly comment on the 1951 film starring Michael Rennie and Patricia Neale (what’s more, I too missed mentioning this movie in my earlier post). The very idea that we humans are our own worst enemy (not the aliens) continues to resonate. Indeed, I would posit that this theme could have everything to do with the Fermi Paradox, i.e. why we have not been formerly contacted by advanced extraterrestrials. The idea here is that “advanced” should not be a term limited to just technology.

“- the travesty that was the film “Starship Troopers”, OK except for the excellent shower scene-”

Starship Troopers the book has a quasi-religious following; there are people who fairly worship it as the greatest SF book ever written. So to some any version that is different than the book is a “travesty.”

Since I am not imprinted like a baby duck with the book I have the ability to watch the movie without being horrified at the blasphemous liberties taken by the films makers.

Anyone that thinks Clancy Brown yelling “MEDIC!” is not in keeping with the spirit of Heinlein might want to take another look.

“each of these craters resulted in instant death in its vicinity, followed by massive forest fires, dust-dimmed sunlight, falling temperatures, and finally starvation over large areas of the Earth.”

The movie “The Road” is my nomination for best hard sci-fi movie in decades; it is so realistic the test audiences walked out depressed and they had to revise the movie and delay it’s release.

An impact would indeed begin what I call “World War C.”

The C stands for cannibalism. After half a decade of not enough sunlight to grow food the world would be mostly depopulated with cannibal armies fighting the last big battles.

Marc Millis wrote (in part):

“What would you guys be willing to pay to download some well-done hard sci-fi about space? And how many of you are there?”

I don’t do movie downloads, but I would happily pay going-rate (or even more, within reason) prices for DVDs of such movies–indeed, California film producer Jeroen Lapré is a big fan of Arthur C. Clarke, and he is working on a film version of Clarke’s short story “Maelstrom II” (see: http://home.comcast.net/~jeroen-lapre/ArthurCClarke/MaelstromII/MaelstromII.html ). [The implied ‘Maelstrom I’ in the story’s title refers to an oceanic maelstrom–a whirlpool–that Edgar Allen Poe wrote about in one of his works, which the main character in Clarke’s story recalls.] The “Maelstrom II” movie will be released next year. I’ve read “Maelstrom II,” and it’s a great–and gripping–subject for a film. Also, here is a link to a “rough cut” preliminary “teaser” video of the film (see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RIX4uU3VCDI ). Also:

This movie version of “Maelstrom II” will have to “cast” a different lunar mountain or mountain range as the “bad guy”; it turns out that the Soviet Range (Montes Sovietici) that figures prominently in the story doesn’t exist at all–the “mountains” are simply an alignment of bright crater rays (see: http://the-moon.wikispaces.com/Soviet+Mountains )! :-) This is no “show-stopper” to the “Maelstrom II” movie though, as there are plenty of confirmed mountains on the lunar farside (see: https://the-moon.wikispaces.com/Lunar+Mons )–Apollo 16’s Particles & Fields Sub-Satellite hit a mountain on the lunar farside after orbiting the Moon for only about a month in 1971. :-) Speaking of Soviet matters:

To Dmitri’s list of classic Soviet science fiction films might be added “Engineer Gerin’s Hyperboloid,” which was–if memory serves–released in 1967.

Oops–I didn’t get the name or the release date of that Soviet film quite right in my reply above. According to the Wikipedia article: “The Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin” (Russian: ??????????? ???????? ??????, translit. Giperboloid inzhenera Garina) also abberivated as “Engineer Garin” is a black-and-white 1965 Soviet science fiction film based on Aleksey Tolstoy’s novel “The Garin Death Ray.”

Thomas Hackney said on February 5, 2013 at 17:47:

“Corrections: Copernicus and Galileo did not believe the STARS were suns. The PLANETS were wandering stars, not planets like Earth. …”

Maybe Copernicus did not know that the other planets in the Sol system were similar to Earth, but then again he was so publicly careful and conservative when it came to astronomy so as not to induce the wrath of the Church, it is not implausible that he at least suspected those wandering lights were actual worlds of some sort. The man waited until he was just about to die before having his ideas published, that is how cautious he was.

Galileo I am much more certain knew not only that the other members of our system were planets and moons, but that he also thought the stars were like our Sun. Galileo was well aware of Bruno’s radical ideas and probably agreed with them in private, but not only was he big on taking the credit for himself, he also wasn’t terribly keen on ending up like Bruno. Permanent house arrest was much less detrimental to one’s health and he could still sneak out his ideas to more tolerant regions of Europe.

The following quote from Galileo speaks rather clearly to me that he had at least some idea of the nature of at least our Sol system and what the rest of those stars might be like:

“The sun, with all those planets revolving around it and dependent on it, can still ripen a bunch of grapes as if it had nothing else in the universe to do.”

I highly recommend The Book of the Cosmos by Dennis R. Danielson for a different take on the subject matter, namely the misplaced view that the ancients thought Earth was the center of the Universe due to its importance; it was more like we were at the bottom of a cosmic pit in the literal and moral sense – Copernicus, Galileo, and Bruno dared to lift us up into the literal heavens:

http://faculty.arts.ubc.ca/ddaniels/cosmos.html

philw1776 said on February 5, 2013 at 21:17:

“I do take exception to the travesty that was the film “Starship Troopers”, OK except for the excellent shower scene. I like some of Verhoven’s other work, notably the excellent “Black Book”, but Troopers should damn him to hell.”

I too am not a slave to Heinlein and I thought Verhoven’s version of Starship Troopers was a rather well done and even bold satire on multiple subjects, if you could put up with the violence and gore. Note some of the eerie parallels between why humans went to war with the Bugs (they dropped a planetoid on Buenos Aires) and the terrestrial reaction to the attack and 9/11 (the film came out in 1997). Reasonable people should also be more than a little disturbed that the “solution” to a politically corrupt human civilization is a global military coup by “benign” officers, where violence is advocated as an acceptable means to an end (the teacher’s lecture near the start of the film).

Sadly, Verhoven’s Starship Troopers arrived in the post-Star Wars cinematic era, where especially American audiences just wanted spaceship battles and aliens who were really humans with a few funny-looking features. Equating American military officers with the Nazis (look at those uniforms!) probably did not help, either.

Just to steer this back to a more Centauri Dreams theme, it would not surprise me at all if it turns out that certain ETI might be similar to the Bugs, including the reaction both sides would have to each others’ presence in the Milky Way. And tell me it would not be implausible, though very sad, that what ultimately gets humanity into space on a serious level would be the threat of extinction from an alien species.

ljk: Bruno and Galileo were brilliant men and ahead of their time. Galileo may have held the apparent truth to himself but I suspect otherwise. Bruno and Galileo both applied for the Mathematics Chair at the University of Pisa in 1589 (I think it was) with Galileo winning the coveted seat. Maybe the younger man felt obliged to disparage Bruno and his ideas for that reason alone. Who can say (what truths lurk secretly in the minds of men)? The Church officially pardoned Galileo in December 1992, but because Bruno loudly bucked the Aristotelean system, among other Church doctrines, Bruno continues to stick in its throat.

GaryChurch said on February 6, 2013 at 16:36:

“each of these craters resulted in instant death in its vicinity, followed by massive forest fires, dust-dimmed sunlight, falling temperatures, and finally starvation over large areas of the Earth.”

“The movie “The Road” is my nomination for best hard sci-fi movie in decades; it is so realistic the test audiences walked out depressed and they had to revise the movie and delay it’s release.

“An impact would indeed begin what I call “World War C.”

“The C stands for cannibalism. After half a decade of not enough sunlight to grow food the world would be mostly depopulated with cannibal armies fighting the last big battles.”

Funny that you mention The Road, as it has been speculated that a comet or planetoid (or even a supervolcano eruption) had struck Earth rather than a nuclear war, based on the few clues in the novel.

http://wiki.answers.com/Q/What_was_the_big_disaster_in_Cormac_McCarthy's_book_The_Road

I read the novel and that was enough for me. Rod Serling was among the first writers of the earlier Cold War era to bring home multiple times that a nuclear war would not be winnable by one side or the other or even survivable. If humanity went that route, we would either be set back worse than the proverbial Stone Age (think the animalistic humans in the original Planet of the Apes) or rendered extinct. No Road Warriors or ten to twenty million dead, tops, depending on the breaks.

Thomas Hackney said on February 6, 2013 at 2:01:

“ljk: Thanks for the link to the very thoughtful article at the end of your missive! He missed two great movies in his list of important pre-Star Wars era sci-fi films: “The Day the Earth Stood Still” (1951) and “Fahrenheir 451? (1966).”

You are welcome. I did not mention those two films (or Destination Moon or Forbidden Planet) because, with the exception of F451, they were outside the timeframe I was referring to in my article, which was the late 1960s to early 1970s.

This is certainly not a negative comment on those 1950s SF classics, only that in the preceding decade those few good SF films were immersed in B to Z grade junk (but often fun junk at least from our perspective). The golden era of SF cinema, as I like to call it, only really began to take off with the Counterculture Era. Those works were the first to mirror the better SF novels, both those they were based on and the genre overall. Television also had its few golden moments as well, though more sporadically.

I know I have missed a few films here and there and that there was plenty of junk during the pre-Star Wars era as well; but the gems really stand out all the more, especially in our time. There is a sad but good reason why 2001: A Space Odyssey has never been duplicated or surpassed 45 years after its arrival (yep, 45 years this year).

A comment on the concept in The Day the Earth Stood Still: While it may be appealing in a way to think that advanced ETI think enough about us at all to consider us potential threats to their galactic utopia, I get the feeling that any intelligent aliens who do dwell with us in the Milky Way probably do not even know we exist, or if they do have not put us at the top of their contact do-to list.

If we do head off into the galaxy making a lot of noise and mess like we on Earth, keep in mind that space is really big and anyone who can travel between stars would probably know how to put us in our place until we learned the cosmic social graces or else.

“it would not be implausible, though very sad, that what ultimately gets humanity into space on a serious level would be the threat of extinction from an alien species.”

I never thought about it seriously until Stephen Hawking went on TV. When people say someone is a genius I usually listen. Really.

As I write in an earlier version of my famous essay “Water and Bombs” on yahoo voices, “It may be a common occurrence in this galaxy for planets to be biologically cleansed with a cometary bombardment to prepare for the introduction of invasive alien species.”

Talking about hard (core) Sci-Fi and The Garin Death Ray. I saw it only once. Don’t remember much of it except the ray which sank the fleet of ships. It had such an impact on me that I tried to build a laser myself. After fiddling w/ fake crystals, lenses and etc I made it. Before liting candle ( candle as a ligth source ;-) ;-P ) I imagined explosions and holes ahead. After the candle was lit was very dissapointed to see nothing. I couldn’t figure out why didn’t work as I didn’t see ray itself. There was not many sources for education on this or anyone to ask for.

Can’t tell why the book and movie had such impression on the whole society, maybe we had also a radio theater version of the book but in Estonia there is band who made it into a song which was a smash hit ;)

Vennaskond – Insener Garini Hüperboloid – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4xAPuSVpXFk

For those who might me intrested in Russian version of the movie – http://kinofilms.tv/film/giperboloid-inzhenera-garina/6612/

James Jason Wentworth thank you for bringing back my childhood memories which I have forgotten and needed an incentive to recall ;)

To complement the list of hard Sci-Fi movies I would advice if you can get hold of to watch:

* Andrei Tarkovsky – Stalker

Andrei Tarkovsky’s take on Strugatsky brothers infamous novel Stalker which differs from the book but made into movie classics.

* Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel (Hukkunud Alpinisti hotell)

Another movie of Strugatsky brothers book which is translated into English as “Inspector Glebsky’s Puzzle” and deals w/ ETI contact and misunderstandings. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0204526/

* Navigator Pirx (Navigaator Pirx)

Movie of Stanislav Lem’s book “Tales of Pirx the Pilot” which deals w/ morality and judgement of AI and robotics. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pirx

All three movies mentioned are either made by Estonians, involved by Estonians or shot in Estonia. They all deal w/ hard core Sci-fi problems.

As icing on the cake.

This is a short movie from 1946 made by aforementioned Pavel Klushantsev called Little Apple – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=__X54d84NdQ . All the SFX you see were developed by Klushantsev. Technical Director of Terminator came to Moscow somewhere 1980s ask about the details how this was made. Klushantsev was at that time retired, lonely and he gave all the technical details and technique to TD. Can’t recall name of the guy but I saw a short interview w/ him describing his adventure to Moscow and how he managed to get hold of Klushantsev w/o speaking Russian. Anyway still a remarkable piece of cinematics even in today’s SFX standards.

Dimitri, you may find this new book to be of interest:

Science fiction helped create modern Russia, says author

By Linda B. Glaser, Jan. 31, 2013

Science fiction as a genre first emerged not in the technologically advanced West, but in largely agrarian late 19th century Russia. As associate professor of comparative literature Anindita Banerjee explains in her new book, Russian writers weren’t reflecting changes happening in their everyday life, but rather visualizing what could be; science fiction became a way of not just talking about, but also of creating modernity in Russia.

In “We Modern People: Science Fiction and the Making of Russian Modernity,” Banerjee addresses the tumultuous decades between the 1890s and the 1920s. She draws parallels between Russia then and globalization today.

Like Darwinism and electricity in the early 20th century, “genomics and robotics, information science and digital media have come to constitute primary indices of tremendous upheavals in our contemporary life and reality. … The pace of science and technology is so compressed that every few minutes something is invented with world-changing potential.”

The audience for science fiction in Russia spanned every part of society, from avant-garde artists to scientists to philosophers to schoolteachers to policymakers.

“Science fiction emerged at the confluence of a revolution in Russian print media and the scientific and technological revolution in the West,” Banerjee said. “These media were obsessed with techno-scientific marvels that were changing the fundamental ways of thinking and living. Science fiction quickly became the preeminent way of visualizing modernity in Russia and what was to come.”

Full article here:

http://www.news.cornell.edu/stories/Jan13/BanerjeeBook.html