by Kelvin F. Long

The chief editor of the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society here offers part II of his article on the Society’s history. If there is one BIS project that captures the imagination above all others, it’s surely Project Daedalus, the ambitious attempt to design a spacecraft capable of reaching a nearby star within 50 years. But the motivations for Daedalus were wide-ranging and the conclusions of the study may surprise you. The success of the design effort showed us what was possible with the technology of its time, while subsequent studies like Project Icarus upgrade the vessel and take us that much closer to what may one day be a working craft.

Les Shepherd took things to new heights with the publication of his seminal 1952 paper “Interstellar Flight”. This was the first paper ever to properly address the physics and engineering issues associated with sending a probe to another star and it is what I regard as the beginning of interstellar studies as a subject. This brings us to one of the seminal studies of the society, Project Daedalus. Speaking to people about the Project Daedalus study, it is clear that many today don’t fully appreciate the real motivation behind it, which was the Fermi Paradox. This is the apparent contradiction between our theoretical expectations for intelligent life in the universe and our lack of observational evidence.

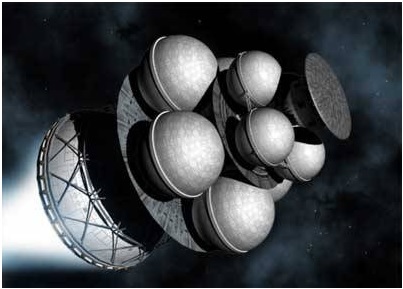

One of the ways to begin to address this is just to ask if it is even possible to travel between the stars (just like the BIS had earlier asked if it was possible to conceive of a machine to travel to the Moon). So the Daedalus team spent five years (mostly in pubs) designing the 50,000 ton unmanned probe capable of reaching 12% of the speed of light. Their guiding principle was to find a balance between being sufficiently bold and being sufficiently credible. This meant that the design had current technology (1970s) and extrapolated technology (few decades hence).

The approach naturally led to design contradictions (i.e. vacuum tubes next to an AI computer) and was the main limitation on the fidelity of the design integration. But most would agree the team did a pretty good job. As Centauri Dreams readers are familiar with Daedalus by now, I won’t go over the design itself, except to say that it would be a 450 ton flyby probe that was delivered to the Barnard’s Star system, 5.9 light years away after a journey lasting around half a century. At the end of the study the team concluded that if at the outset of the space age we can conceive of a machine such as Daedalus where interstellar flight appeared to be possible, then it is likely that in the coming centuries we could derive a more credible and practical design.

On the basis of this, they concluded that interstellar travel was therefore feasible, and so the explanation for the Fermi Paradox may lay in some other solution (i.e. the prevalence of biological life). But Daedalus was the first study to prove that interstellar flight was possible.

Image: The BIS Project Daedalus, a modern illustration. Credit: Adrian Mann.

Anyone who studies aerospace engineering knows that a vehicle design goes through three levels of iteration. First is the concept design phase, which addresses whether it will work, what it looks like, what requirements drive the design, what trade-offs should be considered and what mass it should have — and if necessary how much it would cost. The next level is the preliminary design phase, which freezes the configuration, develops any vehicle sizing, creates the analytical basis for the design and moves into experimental demonstrations if appropriate. The final level is the detailed design phase, which identifies the individual pieces to be constructed. This includes any tools required. It involves any critical design tests of the structure and finalizes the vehicle configuration layout and performance specification.

Along the way, there is a process of integrating the various systems and subsystems, today couched in the language of systems engineering. In my opinion the Daedalus was an early preliminary vehicle design for a starship. The team defined all of the major systems and most of the subsystems. Full integration was not possible due to the nature of the technological extrapolation. But the vehicle configuration layout, performance specification and mission profile were defined in full where practical to do so.

During my own reading of interstellar concepts, I have come across solar sail-driven methods, laser beaming, microwave beaming, fusion, antimatter and exotic concepts, to name a few. All of these studies have been concept papers, however, or proposal submissions, or case study analyses – they do not constitute designs. I argue that at best they are concepts and for most of them even that term is not fully justified due to errors in the calculations or the gaping areas of engineering or physics not addressed. Daedalus is the only one that can be claimed to be a “starship design” in my view. The only other vehicle that comes close to it is the Project Orion design from the 1950s and 1960s. Orion certainly was a preliminary design, but it was calculated for an interplanetary mission only. Then there were the worldship studies from the 1980s by Alan Bond and Anthony Martin, but these did not go into the sub-system level of the internal architecture. Daedalus was first, and Daedalus remains the only one

On a recent visit to NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, NASA Glenn Research Center and the Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop, I challenged people to refute my controversial (and deliberately provocative) claim that Daedalus is the only starship design in history. NASA appeared to agree with me. This is an astonishing revelation and I find it intriguing that people are prepared to pronounce interstellar flight impossible when we have only attempted one such design in history. More feasibility studies are clearly required before we can have a clear picture of what the impossibilities or otherwise are.

There are three profound implications that come out of the Daedalus study which I think are worth highlighting again because they are so important:

- That interstellar travel appears to be entirely feasible in theory and so in the future will likely be feasible in practice.

- That because interstellar travel is feasible, the absence of any observation of intelligent life in the universe suggests we must seek alternative explanations.

- That Daedalus was the first and so far only starship design in history and remains so to this day (until the completion of the Project Icarus study anyway).

In the light of history and developments in astronomy, I suppose an important addendum should now be added to the Daedalus study, which is that a flyby is probably not the way to send a probe to another star. This was the view of the Project Icarus team early on, which is why we made deceleration an engineering requirement for the mission. We live in an age where exoplanets are discovered almost weekly, orbiting around other star systems. In the future we should be able to fully characterise those planets, including their stellar atmospheres, using Earth orbiting or lunar based deep space observatories, so the benefits of flyby must be justified from both a performance and cost basis. In order to add value to an interstellar mission, it is more beneficial to send a probe that can release atmosphere penetrators and planetary landers into the local system, accessing the surface that deep space platforms from Earth cannot reach.

Image: Kelvin F.Long lecturing at NASA Marshall Spaceflight Center, February 2013.

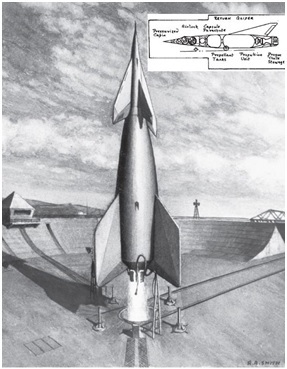

Numerous other BIS projects have been in play, the earliest being development of a coelosat in the 1930s, a device capable of effecting navigation by the stars. Ken Gatland invented the idea of the MOUSE launcher from 1948-1950. The lunar lander underwent various developments by Ralph Smith from 1947-1952. Smith also developed the concept of a space station with Harry Ross from 1948-1958. He also designed a manned orbital winged rocket in 1950. Les Shepherd and Val Cleaver wrote some of the first pioneering papers on atomic rockets from 1948-1949. Arthur C Clarke was also busy during this period, designing his electromagnetic lunar launch system in 1950 and the atomic interplanetary spaceship in 1952. His spaceship design was shown in several popular space books by himself, Gatland and others around that time and it has a striking resemblance to the Ares, the vehicle that features in Clarke’s book The Sands of Mars and also the Discovery I which is the design featured in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Members of the BIS have also been involved in various spin-off projects such as the 1980s HOrizontal Take-off and Landing (HOTOL) project initiated by people like Bob Parkinson at British Aerospace and Alan Bond, then at Rolls Royce. Bond went on to found Reaction Engines Ltd and to develop the groundbreaking Sabre engine, the critical technology required in order to make a vehicle like Skylon (the successor design to HOTOL) technically credible. Charles Cockell launched Project Boreas in 2001, an initiative to design a human habitat at the geographic Martian north pole. The project featured luminaries such as the astronomer Ian Crawford and the science and science fiction author Stephen Baxter, all dedicated members of the society. Other big names have been members of the society throughout its history, including Bob Zubrin, the guy that radically changed our thinking on how to do Mars missions more than anyone. In the 1980s he was regularly communicating with the BIS planetary engineering (terraforming) expert Martyn Fogg, who was then arguably the world authority on the subject.

Image: The BIS Winged Orbital Rocket. Credit: BIS.

I mustn’t forget Olaf Stapledon of course. I am unsure if he ever joined as a member but his famous 1948 lecture on “Interplanetary Man” at the invitation of Clarke was one of those world events that anyone would have wished to attend. I wasn’t born then but was fortunate to meet Stapledon’s grandson Jason Shenai last year. Jason came to the BIS to attend the “Starmaker” symposium which the Technical Committee had organised.

The above are just some examples of major projects the society has pioneered as feasibility studies in the early years, all of which (except for the interstellar probe and SSTO) came to fruition, showing that the society played a vital role in engineering the future. This is what Arthur C.Clarke refers to as “creating a self-fulfilling prophecy,” and this can be achieved by the adoption of positive and optimistic advocacy.

My own entry into the BIS (and indeed the space/interstellar community) was the organisation of the Warp Drive conference in 2007. Speakers came from across the world to London to discuss the developments since Miguel Alcubierre’s seminal 1994 paper. This is where I first met Claudio Maccone and Richard Obousy. It was with Richard’s assistance that we both went on to found Project Icarus, with the goal of catalysing the interstellar community. Those were exciting days. When we look around us at the many interstellar related organisations working on the goal of starflight, we can be proud of our efforts and know that we played some role. Project Icarus was always intended as part designer training exercise more than anything, recognising that there was a lack of design capability to actually work on starships at the time.

The other purpose of the project was to inspire people young and old to believe in the dream of star travel once again. Project Icarus is still on-going as a joint British Interplanetary Society project with the US non-profit Icarus Interstellar, who now manages the project until its completion. Icarus Interstellar have gone on to found many other design projects, taking our original ambitions to a new and hopeful level and I’m proud to have played a role in its foundation. I have also now moved on to found the pending Institute for Interstellar Studies. We and all the interstellar organizations are building the vital industry needed to make interstellar happen at some point in our not too distant future.

On the 13th October 2013 the British Interplanetary Society will be 80 years old. When I consider the achievements of the BIS throughout its history, I am also forced to consider its function. The society is clearly not a science fiction society, but it is also clearly not a commercial space organisation. As a registered charity, I find that its function is in fact unique, in that it exists between both of these worlds. It stands in the metaphorical corridor between “imagination” and “reality” and this is in fact its motto: “from imagination to reality”. People have ideas, concepts, designs, they bring to the BIS and the various mechanisms (lectures, publications, symposia) will help to catalyse those ideas and then to bring them to the attention of wider industry, government and academia.

Nothing exemplifies this more than the example of the BIS Lunar Lander. One wonders whether Daedalus and the Project Icarus study are playing the same role today but for interstellar flight. We also have a role to point the way, to act as a compass direction for future achievements. To help to convince industry, government, academia, the public and the media that something is possible, where the data may have previously suggested it was not. In this way, we encourage innovations and breakthroughs which can lead to new technologies, industries or processes, and thereby greater achievements in the exploration of space.

The HQ building in London is now officially called “Arthur C.Clarke House”, and Clarke twice served as President of the society (then called Chairman) in the years 1946-1947 and 1951-1953. He remains our most inspirational member and we are very proud to carry on with his legacy. It may surprise many to know that although the BIS is the oldest space organisation in the world, it has also been struggling to survive through challenging financial times. Despite this it has continued to serve a vital role for the community at large. The technical publication JBIS, for example, is famous for the publication of its “red cover” issues on interstellar studies from 1974-1991 (we have recently been issuing new red cover volumes), and it has remained the torch holder of the interstellar vision through the decades.

Image: The BIS door bell. Credit: BIS.

Where else would all of those creative talents have found a home for their pioneering and speculative publications on starship design or the Search For Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI)? However, don’t despair, as things are looking up with the election of an inspirational new President, Alistair Scott, who has a charismatic military-based leadership style, from his experience as an Army officer. He originally studied aeronautical engineering at university and after several exciting positions in industry he settled for many years at the satellite company Astrium. Scott is applying this huge experience to driving the recovery of the society, literally running the committees like they were platoons within a regiment. Yet he is as down to Earth and charming as they come and a complete gentleman, showing respect and warmth for all people no matter their background or rank. He is supported by his loyal team, including Vice Presidents Mark Hempsell (Reaction Engines Future Programs Director), Chris Welch (International Space University Professor) and Suszann Parry, the Executive Secretary.

The society has many new and exciting projects coming online under the supervision of Technical Committee Chairman Richard Osborne, a pioneer of amateur rocketry himself. The BIS is participating in Project KickSat, which is an initiative by Zac Manchester out of Cornell University in the US to place a fleet of ChipSats or Sprites into Low Earth Orbit sometime this year. The BIS members put several thousand pounds into the project, which is now managed with enthusiasm by Andrew Vaudin. The society is also launching Project 2033 (managed by myself), a competition to imagine the future state of space exploration at the society’s centennial anniversary. Sir Arthur C Clarke is famous for his ability to see into the future and predict technology trends. We are hoping to find the next visionary and to see twenty years from now who gets it right. We have recently launched Project STARDROP, which stands for Solar Thermal Amplified Radiation Dynamic Relay of Orbiting Power, which aims to design a 10 GW solar collector power system to run an L5 space colony. This is now being managed by Ian Stotesbury. The past projects of the BIS are outstanding but we are looking towards the next horizon in space.

Image: The BIS President Major Alistair Scott. Credit: BIS.

Things seem to be changing in Britain for the better with government attitudes towards space exploration being much more positive. We now have our own United Kingdom Space Agency (UKSA), our own European Astronaut Tim Peak (Britain’s first official astronaut), and as if things could get any better, it was recently announce that a UK industry team in cooperation with UKSA is investigating whether Britain should have its own spaceport…and launch vehicle (yes, you read that right). The company Reaction Engines already has an answer to this of course, with its innovative Single Stage To Orbit (SSTO) spaceplane design. The company recently announced critical breakthroughs relating to the pre-cooler technology which has previously prevented similar concepts becoming reality.

We may be the oldest space organisation in the world, but we are also a thriving organisation, making changes to ourselves so as to better serve the modern technological world. We would love for new people to come and join us and be a part of this great society, with its global outreach and impact. We are particularly looking for members in the US or elsewhere to start BIS branches. The history above proves that the BIS does engineer the future. If this is attractive to you too, and you are interested in being a catalyst to our own determined self-fulfilling prophecy, then you will find a home with the BIS. We welcome new members who want to help take imagination to reality. Be unique, and join the British Interplanetary Society, because it’s where the future is made. And the next time you are in London, be sure to pay us a visit.

Finally, I want to end this article with a donations appeal. The BIS is a registered charity and we are all volunteers, including me, yet I manage to run the journal and keep the papers moving. Our financial demands are high and this has impeded our ability to meet the mission. If you believe that the British Interplanetary Society’s role in astronautics has been and continues to be important, then please consider making a donation and we will carry on doing it. Ad Astra.

==

Donations to the BIS can be made here:

http://www.bis-space.com/products-page/donation/

The main BIS web site is located here: www.bis-space.com

The Technical JBIS web site is located here: http://www.jbis.org.uk/

The information on past BIS projects was partly borrowed from the BIS book Interplanetary by Bob Parkinson and incorporates edited information from articles from the August and September 1967 issues of the BIS magazine Spaceflight. The book is available for purchase here: http://www.bis-space.com/products-page/books/

Les Shepherd’s 1952 JBIS is the first comprehensive essay on interstellar flight that I know of.

(Technical aspects of IF were worked by Esnault-Pelterie in L’Astronautique in 1930, actually work he had done in 1926)

Before the IF paper the BIS had published:

Shepherd, L.R., and Cleaver, A.

V., (1948, 1949), “The Atomic Rocket-1,2,3 and 4”, J. British

Interplanet. Soc., Vol. 7, no.5 and No. 6, 1948; Vol. 8, No. 1 and No. 2, 1949.

Tho Tsien almost got there at the same time (yes that Tsien)

Tsien, HS, “Rockets and Other Thermal Jets Using Nuclear Energy”, The Science and Engineering of Nuclear Power, Addison-Wesley Vol.11, 1949

Shepherd and Cleaver’s work on the atomic rocket was was the most extensive in print for a long time. (The same work was under lock and key at Los Alamos , and did see publication until 10 years later.)

Bussard, R.; DeLauer, R. (1958). Nuclear Rocket Propulsion. McGraw-Hill

One correction:

“But Daedalus was the first study to prove that interstellar flight was possible.”

Freeman Dyson had shown this in “Interstellar Transport,” Physics Today 21 (1968), pp. 41–45.

Daedalus was the first down to the rivet head study of IF but was published 10 years after Dyson’s paper.

Fascinating read. It certainly made me interested in visiting your HQ in London and thinking about membership as well as donating.

Hi Al,

Good comments. However, regarding the Dyson study, my point is that was not a design. What I should have said was that Daedalus was the first design to prove that IF was possible.

Also, in my article I referred to Project Orion but the “design” was only the interplanetary version. Dysons 68 paper, although an excellent read, in no way constitutes a design study, IMO.

I would be interested in reading the 1930 paper. Where can I get a translated copy?

Best wishes

Kelvin

“Freeman Dyson had shown this in “Interstellar Transport,”

Well, he did not actually design a spaceship, just did calculations; and the BIS starship relies on fusion and it is my view that {the only two places fusion will ever work as advertised is in a star or a bomb}. I must have posted that addage fifty times over the years.

I would enjoy reading Paul’s take on the Medusa concept for nuclear pulse propulsion.

Two articles on Medusa:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=23754

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=23765

Awesome; I have some reading to do. Thank you Paul.

Daedalus has been inspiring people to fly for a very long time:

http://www.strangehistory.net/2011/08/14/flight-in-eleventh-century-england/

Wojciech J, please join and yes please donate if you can afford it.

your charity is greatly received and the BIS certainly needs it. For example, right now the boiler has broken down and we need a replacement but can’t afford it – so the three staff we employ are working in cold conditions. Yet, we endure. Thanks for your interest in the BIS.

Kelvin

One thing I am curious about.

The BIS did the amazing (for its day) flight to the moon study, then (decades later) the Dadelus study, and now the Icarus study.

Has the BIS ever tried to do a design study on an Interplanetary vehicle? Especially if they could design a highly flexible reusable one, i.e. one that could go to different planets and moons. After all, the ‘I’ in BIS stands for ‘Interplanetary’.

Dear Kelvin,

Indeed Daedalus was the first end-to-end design of an interstellar flight study… like von Braun’s Mars Project. Well Daedalus was even more detailed.

As far as I know there is not another like. Tho Icarus is working on a new one.

Well Dyson’s article does prove that Orion could attain 1 to 10% the speed of light. I know he had to talk around the design, which at that time was contained to a secret three document set, which I have seen, but is still classified. And the Orion system could and can still be build with the technology we have. I think enough is told in George Dyson’s book Project Orion: The True Story of the Atomic Spaceship.

Not just speaking of possibility, apparently it was Fermi doing one of his famous back of the envelope problems who noticed that the 1% c velocity could be attained, which led , apparently , to the so-called Fermi Paradox.

As to Esnault-Pelteri the whole book is contained in translation in Interplanetary Flight and Communication , N.A.Rynin, NASA TT F-647.

It’s at

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19720011177_1972011177.pdf

Alas , for mad hatter reasoning NTRS is shut down right now … !

I have the hard copy, even the French book from 1930….

I think I have the PDF I will sent it to you.

I think I have the PDF I will sent it to you.

… Say Al, why not put the . PDF file out there for all of us ?

thanks Al. Yes I loved the George Dyson book, was a really great read and George did such a fantastic job. Indeed, the maximum performance for an Orion system is 5%c (A-bomb) and 10% (H-bomb). Orion would work yesterday if you have enough materials.

I know the Fermi story well, but that’s the first time I have read “1%” get mentioned. Do you have a source for that? is that really what Fermi calculated? Fascinating information if it is.

Yes, when Project Icarus is finished, it will be all shiny and new, and we as a team will be proud of the study. But I hope its not like the movies, and you all say “naa! prefer the original”.

RonSmith, you are absolutely right to point this out. I did a recent survey of historical BIS projects (there were quite a few) but the society never did an interplanetary vehicle study. I too found that interesting and have recently advocated within the BIS that this is what we should be doing now. It seems we were either looking under our noses (Earth, Moon, Mars) or looking high up (the stars) and the planets just got missed. Although studies were done into things like gas giant mining of He3 for Project Daedalus. In addition, many authors published papers in JBIS over the years exploring interplanetary mission concepts and some of those were BIS members, but its difficult to call them official projects. So I think the answer to your question is no. Well spotted by the way.

For interest, I believe we got the name ‘interplanetary’ from the American Interplanetary Society. Of course, that organisation changed to the American Rocket Society and eventually merged with another to become the AIAA, so its not the original organisation. Also, from what I can see, AIAA mainly serves the professional aerospace community.

Best wishes

Kelvin

“I loved the George Dyson book, was a really great read and George did such a fantastic job. Indeed, the maximum performance for an Orion system is 5%c (A-bomb) and 10% (H-bomb). Orion would work yesterday if you have enough materials.”

I first read it while helping my wife research a paper for a college class on ethics. It changed my worldview and launched me on this perilous journey as a space enthusiast.

It took a real beating from the critics- I have no idea why unless it was just an anti-nuclear bias poisoning any opinion of it. Indeed, I am not a fan of nuclear energy on Earth- but I am totally pro-nuclear for space travel. In fact, it is my sincere opinion that chemical propulsion is useless for deep space travel.

I wonder if Mr. Long might take a quick look at my essay “Water and Bombs” found on yahoo voices? George Dyson correct a couple errors for me when I first put it on the web. It connects two resources; ice on the Moon and pulse propulsion. The two factors I take into account are cosmic radiation and asteroid interdiction; and both have become news items in the two years since I have written about them. I have not read of anyone else making these connections and I believe it is quite clever.

Gary, will take a look.

Kelvin

@Kevin and Bill

I am still looking through my files for the Esnault-Pelteri translation. File collections are horror shows when you don’t name something that can be found in a simple search!

On the Fermi thing about 1% c. I plead that that was an extrapolation on my part.

I have always been intrigued by the origins of the Fermi (Phil Morrison always called it ‘problem’) paradox. See Eric Jones memo:

http://www.fas.org/sgp/othergov/doe/lanl/la-10311-ms.pdf

It was usual for Fermi to as questions like this, there are a lot of ‘Fermi Questions’.

Then I read , I can’t find it, seems Freeman Dyson said it somewhere that before this lunch meeting at Los Alamos , probably back in Chicago, that Fermi had made a back of the envelope calculation simply using the energetics of fission and fusion to see what velocity could be imparted to a ship, just for fun. He filed away the fact that physics allowed fractions of the speed of light in the back of his mind.

I am not ever sure if this story came from Dyson (I mean Dyson was not there) or someone else of the Los Alamos – U of Chicago groups. It sounded plausible to me since that was the kind of mind Fermi had.

I actually don’t like the term ‘paradox’ in this context although we all use it. A paradox is “an argument that produces an inconsistency, typically within logic or common sense”, as defined by the great Wikipedia.

But I don’t think we have sufficient information to form a logical argument that this should be called a paradox.

Instead, I refer to it as a contradiction.

Theoretically we expect intelligent life to be here.

Observationally we see no evidence for it.

This is a contradiction, and so one of them has to be wrong, or both.

How to address?

1. get out there and look for ourselves. Sample the planets, the ISM, stars…this will improve the observational element.

2. develop an improved model of biology which allows us a better understanding for what is life. This will improve the theory element.

Until both of these are done, we just don’t know and the contradiction remains.

Kelvin

I just finished Benford’s “In the Sea of Night.”

In that novel machine intelligences rule the universe and send robot probes out to find biological intelligences- so they can exterminate them in a pre-emptive act of self-defense.

I hope that is not what is going on. It is possible though. Sci-Fi sometimes becomes fact and that can be…….. disturbing.

I do not think the first claim here in any way implies the second.

Maximum here means “theoretically possible”, I assume. With only the most fundamental constraints of nuclear energy (never mind how converted), the absolute maximum exhaust velocity is around 2% c for fission, and 4% for fusion. So, your 5% and 10% numbers must have a pretty large mass ratio already built in.

Bombs are not likely to get very close to that theoretical maximum, at all. They contain non-fuel inert materials, they burn the fuel incompletely, they generate substantial amounts of energy in non-directable form (X-ray, gamma, neutrons, neutrinos, etc), and even the “good” plasma can not be easily directed out the back at high efficiency. All of which makes me believe that even the lower bound in Dyson’s assumptions (a factor of ten below his upper bound that everybody latches upon and which corresponds closely to the absolute theoretical maximum) will prove highly optimistic in the face of numerous practical challenges. With explosives, in other words, Fermi’s 1% c is already a strenuous reach.

It will take more efficient designs such as fission fragment rockets to really make fast interstellar travel feasible using nuclear energy.

“more efficient designs such as fission fragment rockets”

Fission fragment may work- especially using Americium- but we know H-bombs work. And if you want to speed up or slow down something really big then H-b0mbs scale up really well. Anything trying to contain such energies does not scale up well at all; that is one of the reasons I completely support bomb propulsion. There is alot of plutonium to use but Americium is incredibly expensive stuff- it would take a whole new infrastructure to produce it in quantity.

But if bombs do not work well (very unlikely IMO) and Fission Fragment is what will work I am with you all the way.

“-to really make fast interstellar travel feasible using nuclear energy.”

I do not believe fast travel is possible with nuclear energy- certainly not fission which releases far less energy than fusion. Freezing people uncomplicates using nuclear energy but that technology has not even been researched yet. If I was Bill Gates or that richest guy in the world in Mexico I would be pouring everything I could spare into cryopreservation.

So far the only possibility of time dilation becoming a reality (that is fast!) is my beloved small black hole engine- sometime in the next century. It is the only scheme that does not require unobtanium.

I think it’s worth pointing out a fourth profound implication that came out of Daedalus: it made the famous Drake equation obsolete.

The Drake equation assumes that all the sites at which technological life is located are the same as the sites where those species evolved from non-technological precursors. Daedalus, together with the 1984 worldship studies that succeeded it, demonstrates that technological life is likely to also be found at sites which it has colonised, which are not taken into account in the Drake equation, and which are likely to outnumber the sites at which biological evolution is possible by orders of magnitude.

Stephen

Kelvin, Fermi’s question does not lead to a contradiction, unless we are reasonably certain that life originated a significant period of time before the formation of the Solar System. Correct me if I am wrong, but my understanding is that at present the method and location of the origin of the first living cell in the universe remain totally unknown, and purely speculative. When a fact contradicts a speculation, then the fact wins, no matter how tempting the speculation!

Stephen

“When a fact contradicts a speculation, then the fact wins, no matter how tempting the speculation!”

Absolutely, that is why all those “round-earther’s” are wrong!

“Indeed, the maximum performance for an Orion system is 5%c (A-bomb) and 10% (H-bomb). Orion would work yesterday if you have enough materials.”

“Bombs are not likely to get very close to that theoretical maximum, at all.”

Bombs are more likely than any other scheme to exceed their theoritical limit. The fact that goes unappreciated is that H-bomb external pulse efficiency become more efficient as it is scaled up. This is the opposite of any scheme that attempts to contain such energies.

If you want to kick several hundred million tons of starship like a soccer ball in the right direction there is only one way to do it- and do it over and over again a couple thousand (or million) times.

By definition, nothing can exceed the theoretical limit. And, no, bombs are not more likely to get close to it than other methods, because of the problems I mentioned.

Have you seen pictures of a soccer ball being kicked? You’d need some mighty fine leather for such a “starship”.

“By definition, nothing can exceed the theoretical limit”

Excerpt from wiki entry on Thermonuclear Weapon

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teller%E2%80%93Ulam_design

The “special material” is thought to be a substance called “FOGBANK”, an unclassified codename, though it is often referred to as “THE fogbank” (or “A Fogbank”) as if it were a subassembly instead of a material. Its composition is classified, though aerogel has been suggested as a possibility. Manufacture stopped for many years; however, the Life Extension Program required it to start up again – Y-12 currently being the sole producer (the “unique facility” referenced). Manufacture involves the moderately toxic and moderately volatile solvent called acetonitrile, which presents a hazard for workers (causing three evacuations in March 2006 alone).[12]

The amount of research done on nuclear weapon design is……unknown. It is known to be in the trillions since the first bomb. I significant amount of supercomputer simulation time is dedicated every day on this planet to nuclear weapons research. It never ends. They may not have heard about your theoretical limit.

I am not sure what you are saying. That highly educated physicists with trillions to spend have not heard of the theoretical limits of nuclear energy? Think again. That trillions of dollars can be used to bribe your way around the laws of nature? Think again. That Ulam’s genius somehow enabled him to transcend those laws by using a “special material”? Think again.

I think Ulam would not like these ideas of yours, not one little bit. He was a good physicist, after all.

“I think Ulam would not like these ideas of yours-”

He is not around to comment.