Tau Zero founder Marc Millis and I will be among those interviewed on the upcoming History Channel show Star Trek: Secrets of the Universe, which will air this Wednesday at 10 PM Eastern US time (0200 UTC on Thursday). Being a part of this production was great fun, especially since it meant flying out to Oakland for a visit with my son Miles, who is now actively involved in interstellar matters. On long car trips when he was a boy, I would have Miles read Heinlein, Andre Norton and the like aloud while I drove — terrific memories — so you can imagine what a kick it is to see him as mesmerized by the human future in space as I am.

The idea of getting a payload to another star seemed closer in the days of those car trips. I’m sure that’s because we were coming off the successful Apollo program and assumed that a similarly directed effort could push us rapidly to the edge of the Solar System and beyond. It was in 1975, the year of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (the last time an Apollo flew) that Robert Forward introduced a singularly aggressive idea, an interstellar roadmap that he presented to the Subcommittee on Space Science and Applications of the House Committee on Science and Technology, which had requested proposals outlining possible future steps in space.

Forward called the proposal “A National Space Program for Interstellar Exploration.” Although it was published as a House document, it never received much by way of media attention and was never up for consideration by Congress. It says something about both Forward and the optimism of at least some in the space community that his proposal was so far-reaching. Consider this excerpt:

A national space program for interstellar exploration is proposed. The program envisions the launch of automated interstellar probes to nearby stellar systems around the turn of the century, with manned exploration commencing 25 years later. The program starts with a 15-year period of mission definition studies, automated probe payload definition studies, and development efforts on critical technology areas. The funding required during this initial phase of the program would be a few million dollars a year. As the automated probe design is finalized, work on the design and feasibility testing of ultra-high-velocity propulsion systems would be initiated.

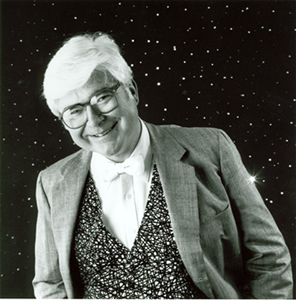

Image: Interstellar theorist Robert Forward, wearing one of his trademark vests. Credit: UAH Library Robert L. Forward Collection.

Let’s pause there for a moment to consider that Forward was talking about the first launch of an automated interstellar probe somewhere around the year 2000, with the first manned missions beginning in 2025. The date reminds me of my friend Tibor Pacher, who heads up the Faces from Earth project, and who challenged me to take him up on our interstellar bet, which you can read about on the Long Bets site. The prediction is that ‘the first true interstellar mission, targeted at the closest star to the Sun or even farther, will be launched before or on December 6, 2025…’ Tibor supports that statement while I challenge it, but either way a good cause wins: If I’m right, the Tau Zero Foundation collects our $1000; if Tibor wins, it goes to SOS-Kinderdorf International, a charity dedicated to orphaned and abandoned children.

But back to Forward in Congress. Imagine the reaction of lawmakers reading on in the scientist’s proposal:

Five possibilities for interstellar propulsion systems are discussed that are based on 10- to 30 year projections of present-day technology development programs in controlled nuclear fusion, elementary particle physics, high-power lasers, and thermonuclear explosives. Annual funding for this phase of the program would climb into the multibillion dollar level to peak around 2000 AD with the launch of a number of automated interstellar probes to carry out an initial exploration of the nearest stellar systems.

And with the ‘damn the torpedoes’ optimism that always marked Bob Forward, he finishes this introduction with:

Development of man-rated propulsion systems would continue for 20 years while awaiting the return of the automated probe data. Assuming positive returns from the probes, a manned exploration starship would be launched in 2025 AD, arriving at Alpha Centauri 10 to 20 years later.

Now that’s moving — Alpha Centauri in 10 years would have to mean you’re getting pretty close to 50 percent of lightspeed at cruise, taking into account the necessary deceleration upon arrival. Forward’s own work would later include an Epsilon Eridani mission concept using a laser-beamed lightsail that would reach 30 percent of lightspeed, one that would be built in a ‘staged’ configuration so as to allow not only deceleration into the Epsilon Eridani system but eventual crew return to Earth. So the man thought big and his ideas were as bold as they come.

Michael Michaud, who would have been developing his ideas at roughly the same time, published a lengthy plan for moving out into the Solar System and beyond to the nearest stars in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society in 1977, a program I want to talk about soon. But first, we need to address a slightly earlier program for interstellar flight written by G. Harry Stine and published in the science fiction magazine Analog in 1973. Stine not only had big ambitions, but he thought he knew just the kind of starship to propose for the job. We’ll talk about Stine’s “A Program for Interstellar Flight” tomorrow.

Forward’s presentation to Congress can be found in “A National Space Program for Interstellar Exploration,” Future Space Programs 1975, vol. VI, Subcommittee on Space Science and Applications, Committee on Science and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives, Serial M, 94th Congress (September, 1975).

I find it difficult to believe anyone thought we would be doing intersteller exploration by 2000 in 1975. The Apollo program was long over by 1975. Von Braun’s Mars mission, proposed in 1969, had been rejected by NASA. The American public had little interest in space by this time, viewing it as a waste of money. Indeed, public attitudes towards technology in general, and large government funded technology in particular, had soured.

Ironically, 1975 was the year the L-5 Society burst out on to the scene, and large scale space colonization, mostly in the Earth-moon system, was viewed as possible by 2000. The L-5 scenario was still just another big government program. But the key difference was that there at least an attempt to get the scheme to pay for itself by selling space-based solar power to Earth-based customers.

I was 13 years old on a family trip in summer of 1976 when I first learned of O’niell’s space colony idea. I was absolutely enchanted. The part about building the solar power stations was appealing as well because this was the decade everyone obsessed over the energy shortage and space-based solar power seemed like a good solution.

The idea that industry and civilization should expand out into the solar system over, say, a 2-3 century period made sense to me. Once a large and diverse solar system wide civilization with millions of people living in thousands of space colonies and the mining of asteroids and what not, that this was the technical civilization that can easily develop the necessary technologies and would have the finance to do interstellar travel. I always thought of interstellar travel as a 22nd or 23rd century thing.

The recent work of Woodward and others is suggesting that it could come a lot sooner.

I think that a “objetives roadmap” is better that a “time roadmap” except for the objetives on development.

Perhaps only a “orientative time roadmap” depending of the real development of the objetives.

A interstellar journey is a project so big that the time lime goes beyond our capability to project the future with precision.

In the U.S. at least, the federal government has always taken the lead in big infrastructure development, whether it’s canals, railroads, highways, or the internet. Expansion into the solar system and beyond will be similar. Lots of problems to be solved and money to be spent before anybody sees a profit. The alternative to big government programs for this is very likely nothing.

How very, very deflating it is to learn from the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry’s Robert Sheaffer and his trio of distinguished (but elderly) scientists that interstellar travel is preposterous! And to think that this blatant verity has been hanging before our noses since the 1960s — alack, alas!

I wrote to Robert in the 70’s soliciting advice in picking a graduate school for someone who wanted to build starships. He wrote back with an encouraging letter. I got to meet him in person while attending one of Marc’s workshops years later. I wasn’t aware of his “Future Space Programs”, it was his “Guidelines to Anti-gravity” that had caught my attention.

I hosted a two hour international radio broadcast from San Marcos California in August 1976, moderating a panel including the L-5 Society and NASA JPL. This took place during the 1976 Western Amateur Astronomers Convention of which I was the convention chairman. President John F. Kennedy had a great vision for the U.S. role in space. By this time we were to have a self sustaining city and factories on the Moon and a Colony on Mars. Perhaps most important of all was a “real” space station with artificial gravity which requires station keeping. From this station we could do final assembly and launch interplanetary spacecraft using ion excited mass reaction motors. To this end I was tasked to turn my optical process into a full scale production of the power relay system required for station keeping. No sooner were we funded when the current administration “stole” our appropriated funds to fund the Space Sail mentioned in this article. It is in my opinion a hoax since the theory has been proven wrong by the results and two years ago the proponents who got $70 million dollars were claiming near light speed capability. Now I see the claim is a more modest 30% LS but still will never happen. Based on experiments it might even drift backwards. Point is that this was a political payback as is much of the wasted Space Program. Our power system was funded for $20 million and would have given us that foothold in space that if by some undiscovered quirk of physics, the Space Sail could be made to work it would still have to have. We were never going back to balloons for spacecraft, we are doing that again. We were never going back to uncontrolled water recovery spacecraft and Orion, canned over thirty years ago is being brought back to do just that. The ISS which by treaty, we have to maintain, is, was and always shall be a sad joke when we could have had a real space station-space launch platform with AG. We have extended our participation in the thirty year old (obsolete when launched) program another four years because some Johnny-come-lately countries now want in without the upfront costs while also wanting us to pay for continuing construction and service. So by treaty we have to maintain it and by treaty when everybody else has their own more advanced programs in place (Russia has a bigger and possibly better shuttle already) U.S. taxpayers at the cost of our own space program is on the hook for that. We should have and could have been making heavier and better spacecraft components on the moon and lifting to orbit for a lot less than pushing higher Gs through atmosphere. As long as we elects the dogs, we will have to forget the bone.

The problem with big programs is that they tend to have a finite life-time, subject to political whim. What’s needed is a self-sustaining interstellar industry/economy with pay-offs on Earth, then near-space, the solar-system, then between the stars. A spiral of technological application to broader humanity, but with activity growing towards starflight.

So what’s the best way forward? Ideas, anyone?

Abelard Lindsey said on May 13, 2013 at 11:02:

“I find it difficult to believe anyone thought we would be doing intersteller exploration by 2000 in 1975. The Apollo program was long over by 1975. Von Braun’s Mars mission, proposed in 1969, had been rejected by NASA. The American public had little interest in space by this time, viewing it as a waste of money. Indeed, public attitudes towards technology in general, and large government funded technology in particular, had soured.”

Among that which can be blamed for his attitude is Richard Nixon and his cronies – and not just because of Watergate, for he did a lot to remove anything founded by JFK out of spite for losing the 1960 Presidential election such as the Apollo program – and the counterculture, which saw anything that even sniffed of military technology to be bad. They all wanted to return to some idyllic Eden, which was already impossible on a massive scale without causing massive genocide for most of the human race.

The vision of the future from less than a decade earlier had been deemed wrong and absurd, where technology and progress were labeled harmful to humanity and our planet. Ironically, it was those very items which did a lot to turn around the looming problems they predicted, such as massive famine and pollution. Soylent Green was originally supposed to happen in 1999 when Earth would have seven billion humans dwelling upon it and over 40 million living in New York City alone.

Abelard then said:

“Ironically, 1975 was the year the L-5 Society burst out on to the scene, and large scale space colonization, mostly in the Earth-moon system, was viewed as possible by 2000. The L-5 scenario was still just another big government program. But the key difference was that there at least an attempt to get the scheme to pay for itself by selling space-based solar power to Earth-based customers.”

Many rocket societies all over the globe got their starts in the 1930s during the Great Depression. I well remember how the L-5 Society had me thinking we would be living in massive space colonies by now. Then again, NASA once had me thinking there would be bases on the Moon andMars by the Year 2000, too. Now we have the SF film Elysium coming out in August, which says that only the rich and powerful will get to live in space aboard one of these luxury colonies, while everyone else has to grovel for survival on Earth. Another negative message to the masses we have to fight against.

An Infinitude of Tortoises said on May 13, 2013 at 21:34:

“How very, very deflating it is to learn from the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry’s Robert Sheaffer and his trio of distinguished (but elderly) scientists that interstellar travel is preposterous! And to think that this blatant verity has been hanging before our noses since the 1960s — alack, alas!”

In the early (and not so early) days of SETI, in order to separate themselves as much as possible from the UFO crowd plus give a rational reason why aliens would send radio signals and not starships, the idea of interstellar travel had to be downplayed.

They did have some good points, and anyone who reads Centauri Dreams knows that getting to Alpha Centauri is not going to be easy, but they often would use the most excessively technological examples to show how nearly impossible it would be to expect the Starship Enterprise to become reality.

Case in point: I was at a SETI conference at Harvard University in 2000. In the slide show presentation (an overhead, please note), they used one sketch of an antimatter-powered starcraft and explained how difficult it would be to build and operate such a vessel.

And that was it. No other discussions of any other kind of craft, not even Daedalus or Longshot. The idea was to make interstellar travel seem near science fiction and therefore only altruistic scientists would be beaming just information back and forth across the galaxy, not themselves.

Yes, it is cheaper and easier and safer to send radio or light signals from one star system to another. Yes, interstellar travel is tough and some forms are tougher than others to make reality. But to assume and make it look like no one would ever attempt to make an operate a starship of some stripe is just narrow-minded to be polite about it.

This bias is why Optical SETI had to wait over two decades to be elevated to the same level as Radio SETI, even though it would transmit more information and even videos than radio. The SETI guys had started out with radio and that is what they stuck with. And only nowadays is the mainstream SETI community even tolerating the idea of alien probes observing us from within the Sol system.

SETI has always had to struggle to gain acceptance and funds. It can afford even less to be narrowly focused these days. Or assume it knows what a truly alien mind might think and do.

It was Freeman Dyson’s article “Pilgrims, Saints, and Spacemen” in the August 1979 issue of L-5 News that convinced me that there would be no space colonies by 2000-2010 period, like the L-5 people expected.

Nice to see some facts being presented about who was pro-space exploration and who wasn’t. I’ve been slammed for pointing out that is was liberals JFK and LBJ who got us to the moon, and the conservative (relatively; not by today’s standards) Nixon who cut funding for the space program. The “liberals-took-the-money-from-space-exploration-and-gave-it-to-people-on-welfare” trope seems to be widely believed. Actually welfare was the conservative solution, as opposed to the Great Society programs which were trying to end poverty rather than just put a bandaid on it.

As for SETI, there have been a few searches for possible alien probes. These (and SETI searches generally) will become more feasible as various all-sky instruments become available. Also there is a growing belief that we should be looking for anomalies in all sorts of astronomical data rather than focusing entirely on planned SETI searches.

NS said on May 14, 2013 at 18:01:

“As for SETI, there have been a few searches for possible alien probes. These (and SETI searches generally) will become more feasible as various all-sky instruments become available. Also there is a growing belief that we should be looking for anomalies in all sorts of astronomical data rather than focusing entirely on planned SETI searches.”

Yes and it only took about fifty years after Project Ozma.

We need to search for and examine infrared sources that do not have an optical counterpart. While we may get lucky catching an electromagnetic transmission, we will do better at this point checking for advanced aliens conducting astroengineering projects.

Yes, I know that can be a long shot too, but until we actually start sending multiple probes to the stars, looking for the highly advanced and visibly hi tech ones will have to do if we want current SETI to succeed. Assuming they don’t beam directly at us or pay us an open visit with their own star vessels.

I want to get back to what Forward said He mentions 4 technologies

One is Laser Sails, another is fusion Daedalus/Icarus and Thermonuclear is Project Orion and then another with elementary particle physics.

Some Questions esp for Paul because he has read so much of Forwards work.

Forward was a realist and brilliant engineer

What made him think we could get to a quarter of light speed with these technologies by 2000?

Have we missed something in his work?

I say this because

We know the Icarus problems and the laser sizes we need for light sails…

The only one we could do now that I see is Orion and I think we could do 1% light at best so Alpha Centauri in 400(BTW for the cost -I say do it)

Finally What was the elementary particle physics he was talking about ?

This is quite a find and I really think Forward was maybe thinking about that we have missed. OK maybe just hoping

David writes:

Forward was an optimist who believed in pushing hard for his ideas. Did he truly believe we could do all these things by 2000? I simply don’t know. I suspect he was being deliberately provocative and not charting out a future he thought would happen that fast. I think he wanted to get the ideas out there, make it clear that they were within the laws of physics, and cause thinking in high places about such matters. So he was intentionally aggressive in his schedule, in my view, partly as a rhetorical strategy.